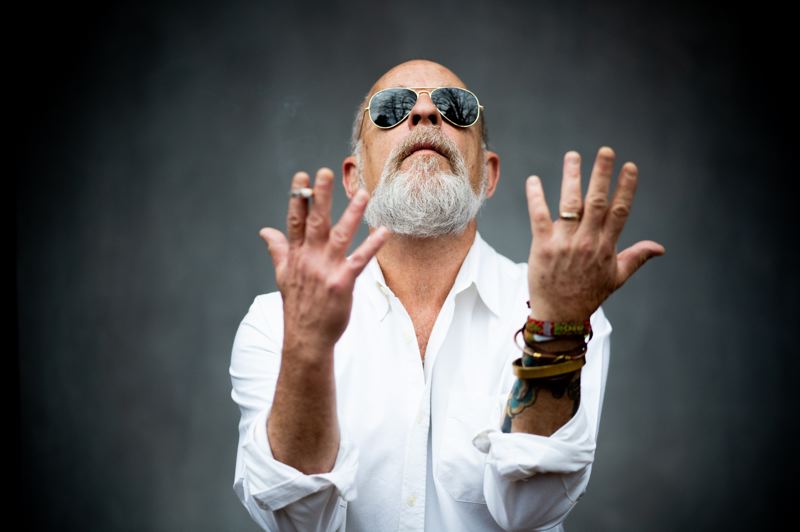

Track By Track: Jerry Joseph: The Beautiful Madness

It’s been over 20 years since Jerry Joseph first invited the Drive-By Truckers to open for him on the West Coast. And while Joseph remained a fan of the Southeastern group during the two decades that followed, their paths infrequently crossed.

However, that changed in 2015 when the Truckers’ Patterson Hood relocated to Portland, Ore., where Joseph has long resided. The two connected once again over pho [Vietnamese soup] and Joseph eventually asked Hood to produce his new record, The Beautiful Madness, which also features guest appearances by Hood’s longtime bandmates.

Joseph explains: “The whole journey started with writing songs and sending them to Patterson. Eventually, we had 30 or so songs that had never been played live. That’s never happened to me. I make my living playing gigs and, usually, I write a song, teach it to the band during soundcheck and we play it that night. But this was the approach that we decided was best. Patterson has not only become a really good friend, but he’s also been pretty influential as far as what I’ve been doing with my career during the past two years— even down to the new record’s name. Hell, what I wore to the album photo shoot was pretty heavily influenced by Patterson’s opinion.”

Days of Heaven

My main intention on this record was to write about marriage. Everyone writes about relationships, and it’s usually the beginning of one— “I saw her across the bar, she’s my spirit animal, she fucks like a jaguar.” They write that song or they write about the breakup years later—“Oh, my God, she cut my fucking heart out.” They don’t often write songs about what happens in the middle of all that. It’s your 10th wedding anniversary and you’re washing the dishes and you look at your wife and ask, “Do you even like me?” And there’s a long pause before she answers, “Well, I love you.” That’s the stuff that interests me as far as relationships. We’ve got the babies, we’ve got the house, but how do we stay interested in each other? How do we stay friends? How does the other person know that any of that stuff still holds—the attraction and the infatuation?

I always steal titles from famous movies or books. Sometimes, if I can’t think of a title, I’ll just stare at the bookshelf and steal something. I thought, “These are the days of heaven—not when we met. It’s this moment.” I was trying to portray that.

Bone Towers

“Bone Towers” is another song that talks about a relationship this far in. What’s funny is that—when I played it for my wife for the first time—I don’t think it hit her that way, which I thought was sad. But it’s like, “Here we are in the middle of our relationship and where do we go from here?”

The “bone towers” is a reference to a real building. I started this nonprofit where I take guitars to active war zones and work with kids in refugee camps. We were in the Sulaymaniyah region of Iraq—in Kurdish Iraq. We were staying in this guarded professor apartment complex in the university. It was next to these unfinished luxury apartments. You see this all over the third world, particularly in war zones— people started putting all this money into something and then basically had to run. There were three towers—just concrete skeletons with no glass—and we kept referring to them as the bone towers.

That was one of the songs that Patterson really latched on to. He had me sing it very differently than I normally sing. I wanted to sing it like Bobby Blue Bland, but he told me I had to sing it in this lower register.

Full Body Echo

“Full Body Echo” is about those people who reverberate throughout our whole being and make us who we are. In a lot of ways, we’re just a walking echo chamber of all these relationships.

There are times where I’ll smell a certain perfume, and I’m instantly with my grandma or I’ll taste a certain food and, instantly, I’m six years old. I think there are echoes of all the people who are important to us, within us.

When it comes to ex-lovers or intimate relationships, I wasn’t always the good guy. I’ve heard: “I was so in love with you and you broke my heart.” The 26-year-old me had no idea. So part of me would love to be able to go back through my whole life— through all those echoes— and say, “I’m sorry.”

San Acacia

My best friend’s daughter, Acadia, was also my older daughter’s best friend. She had one arm, but grew up to be this badass woman who’s accomplished anything anyone with two arms could accomplish—maybe more. She’s also kind of a quintessential woke 30-yearold Portland woman.

One day, I was driving down the highway on my way to El Paso, and I passed a sign that said, “San Acacia, next right.” So I texted her that I didn’t know there was a Saint Acacia, and we started this conversation.

When I got to El Paso, I realized that—though I’ve been to a lot of the world’s most dangerous places—I hadn’t been to Juarez since I was a kid. So I decided that I was going to go to dinner there and find a taco shop. When I got to the walk across bridge, the border guy was like, “What the fuck do you think you’re doing?” I told him: “I’m going to walk across this bridge, I’m going to walk into the plaza and I’m going to get some tacos.” He kind of looked me up and down and said, “Keep your hood up and be ready to run.”

It might be one of the most evil places that I’ve ever been, and I’ve been to some pretty goddamn dark-ass places— Dachau or the Killing Fields or Halabja in Iraq. I also think Charleston has some evil vibes to it. Millions of slaves came through that harbor and there’s no sign that says, “We’re sorry.” Juarez is a heavy place because of the women who disappeared down there. I just started writing that song in my head, and by the time I got to where I was headed—my brother’s place in Mexico—it kind of wrote itself.

So it was a combination of things, and I turned my young friend into this goddess-type figure of an evil place.

(I’m in Love With) Hyrum Black

John Barlow, who was a pretty good friend of mine, brought me in as a writer on a project with Bob Weir and Lukas Nelson, where Weir wanted to do a record of Mormon cowboy songs—particularly Mormon outlaw songs. My band is called The Jackmormons—I lived in Utah for a long time and I know as much about the Mormon church as my returned missionary LDS bass player.

When the songwriting process started, we were writing lines by text. I was in Mexico City on an aborted trip to Cuba and decided to rent an apartment in the Roma Norte. These songs were going by text from Mexico City to Hawaii— where Lukas was—to the Bay Area. While I was waiting for the next line of a different song, I wrote this one.

The idea is that when the Mormons came West, they believed they also had a divine blessing from God to take whatever they wanted, so they would take your cattle, they’d take your food. Brigham Young was one of the more remarkable people in the American West, but he wasn’t a nice guy. Utah came into the union as a slave state. Eventually, when they settled down, they ended up with all these soldiers who had been part of Brigham Young’s elite archangel squad. They were suddenly out of work, and a lot of them became outlaws.

Now, I rarely do character songs. All my songs are about me but, on this record, there are two—“Dead Confederate” and this one. In this one, I’m a young Mormon girl betrothed to a Mormon outlaw. I was really interested in writing from a young girl’s point of view. She’s marrying the outlaw; she’s riding out into the desert because he promised to lay down his guns and follow the book.

Although we never made the album, Bobby did come out and play this song with me at Barlow’s memorial because Barlow loved it. That was super cool of Bobby because the whole thing was about playing Barlow songs, but we did an original of mine. It was just me, Bobby and Steve Kimock.

Good

This song begins with me ranting and ends with all the beautiful things I tell my children about.

I have some friends down on the Mexican border who work with No Mas Muertes. They’re the people that put water and food out in the desert for the migrants coming through with the coyotes. There’s another guy who’s a biologist for desert fauna and, a few years ago, they started seeing jaguar tracks in Arizona. Then they put this wall up and it was all over. Besides stopping humans who are desperately trying to have a better life, the environmental impact of Trump’s wall is horrific.

But I wanted to end the song with these amazing things that are going on. The Jaguar’s coming back, we’re finding planets every day that are the proper distance from their suns to sustain life. When I was in the Arbat Syrian Kurdish refugee camp in Iraq, these girls who don’t speak any English learned how to sing “Happy Birthday” to my friend Charlie. They practiced all night; it was a remarkable moment.

Sugar Smacks

I was alone in Mexico, I had that one chord going and I wrote this song as fast as I could write it. The opening line talks about reading Death’s End [the third book in Liu Cixin’s Three Body Problem trilogy]. I was super surprised that I didn’t get hit with a shit ton of editing from people.

That one’s about where my head was at that moment with politics and trying to digest everything I was reading. I think I’d also just finished Orphan Master’s Son [by Adam Johnson], which is an amazing book about North Korea. So I started spewing things out and, at some point, I started namechecking shit like Johnny Thunders, Joe Strummer, Murakami, Lester Bangs and Flannery O’Connor.

Every line in the song is true to me. Some people have been like, “You can’t say that about the monks in Nepal,” and I’m like, “But I was up there; I was watching them watching digital porn on their phones.”

I finished it and sent the recording to Patterson. He thought it was the most brilliant, punk-rock thing I’d ever written. Originally, it was a centerpiece of the whole record, which is how this record went from being about marriage to being about my worldview.

Dead Confederate

This song is told from the perspective of a confederate statue getting torn down. I’ve been getting some unexpected feedback on this one so, to be clear, I’m not defending this position. The narrator was fighting on the wrong side. I’ve done my reading on the Civil War and there is no doubt in my mind that, at the end of the day, it was about slavery.

I’ve traveled through the South and I’ve listened to some renowned people talk about how the war was actually about Northern industrial aggression against an agricultural way of life. Nope—I never finished ninth grade, but I have a friend who was a history teacher and gave me this big stack of books. I read them all and my position hasn’t changed. The war was about slavery and that’s what I’m commenting on with this song.

I’ve been to all those little towns in Germany. There are no statues of Rommel and he was the Desert Fox. He took all of North Africa and wasn’t even very affiliated with the fucking Nazi Party. But there are no statues of him because he lost, and he fought on the side of evil. So, I cannot be clearer about it.

Black Star Line

I was writing songs for a different record the night David Bowie died, and this is me just talking about how important he was to me. When I was a little kid, I remember going to see the Station to Station tour. He came out and started the concert by asking, “How many bisexuals are out there?” Me and my friend went, “Us!” We had no idea what that was.

It’s just my take on being a little kid and listening to him. The song didn’t make that earlier record and then, when Patterson heard it, he was like, “How come this song has not come out?” I was trying to do something a little different. I’ve been influenced by all sorts of British bands but that sort of glammy stuff really resonated with me when I was a kid.

We’re at this age where our heroes are going to die—they’re getting old. So, I heard the news in the middle of the night and this was my response to it. His Black Star record had just come out on Friday, and he died on Sunday night.

Eureka

This song was completely unfinished. What you hear on the record is me making up the words while I’m singing the vocal track.

My mother, Patricia Duffy, was an adopted child in Eureka, Calif. My grandpa ran the candy tobacco distributor for Humboldt and Del Norte County. I’m fifth-generation Humboldt on my mom’s side. Her mom died right after childbirth and her father gave my mom to his wife’s brother but he kept his son. It’s an incredibly sad story, but he gave up this little girl so she could live on the better side of the tracks. He actually came back four or five years later and tried to get her back, and it was a big Eureka court thing. My grandma and grandpa had the money so they won, and they were never giving her up. My mom grew up going to school with her biological brother who was from the not good side of the tracks. It’s a brutally sad story.

Eventually, she met my dad, who was from East LA, got a scholarship to HSU [Humboldt State University] and became one of top marine biologists in the world. She told me that, one day, she was walking along the Great Wall of China and she realized that little Patty Duffy had made it out. My parents were about as well-traveled as anyone that I know. And while my dad had all these friends at HSU, she hated going back. I can remember looking at my mom on the day of his funeral, knowing that she was never going to go back to Eureka, and she hasn’t.

My mom kept saying she wanted me to write a country song about her and so I wrote this one. I’ve spent a lot of my life trying to write great George Jones songs and I’m not as good at it as Elvis Costello. Patterson loved it, though. When we started cutting it, I was making up words while I was singing. Then I said, “Let’s go back and fix whatever the hell I just said,” and he was like, “No, man, this stays exactly as it is.”