Preservation Hall at 60: Culture Is A Verb

photo credit: Chris Granger

***

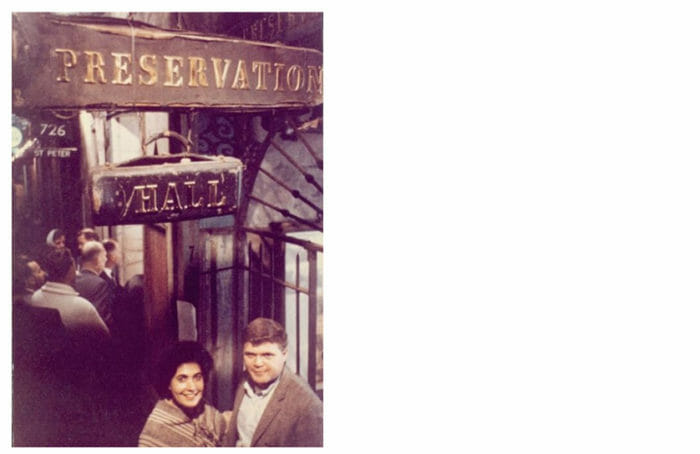

Sandra Jaffe, who co-founded New Orleans’ hallowed Preservation Hall, passed away on Monday. Our October_November issue features a cover story on the 60th anniversary of the venerable institution that Sandra created with her husband Allan.

***

“My parents’ greatest creation was to offer the world this gift, by celebrating the African-American music tradition that had transformed them enough that they uprooted their lives and moved to New Orleans,” observes Ben Jaffe, the son of Allan and Sandra, who spontaneously settled down in New Orleans and founded Preservation Hall during the summer of 1961 following an extended honeymoon trip.

Sixty years later, the Hall occupies a unique place in the city and beyond, as 89-year-old clarinetist Charlie Gabriel, who remains an active member, affirms: “Preservation Hall stands at the foundation of preserving, protecting and perpetuating this music. By playing in the Hall, being a part of the Hall and even just being in the Hall, you can share in the spirit of so many great musicians that have left. What they played is still in the atmosphere, it stays in the atmosphere. It never goes away.”

Ben Jaffe is a lifelong New Orleans resident, born a decade after his parents relocated to the city. The bass and tuba player—who has long since taken up the mantle as creative director of the Hall— adds, “Their whole approach was, ‘We’re here to make this tradition available so that everyone can be transformed by the experience the same way that we were.’ My parents had the ability to bring people together. Dad wasn’t some world-class tuba player. He was the guy with the tuba who was here doing the work.”

That work has been particularly challenging over the past couple years, due to COVID-19 and, more recently, Hurricane Ida. Looming over all of this is the specter of Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall exactly 16 years prior to Ida and set the Hall on a new path.

“Ida made me realize that Katrina is this wound on my soul that has never completely healed,” Jaffe acknowledges. “Some days you don’t notice it because it’s just a part of your body and your soul. But then there’s a moment, all of a sudden, when it comes out. Sometimes it comes out as anger and frustration. Sometimes it’s just tears. Sometimes it’s a prayer—a thanks that we’re still here and an acknowledgement of people like Fats Domino, Professor Longhair, Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong and everything they endured to give us this blessing of music. I could also talk forever about Charlie Gabriel, Wendell Brunious, Shannon Powell and how important they are to me, to the Hall, to New Orleans, to all of us. With Katrina, COVID and Ida, I’ve come to experience how something so devastating has led to so many beautiful moments.”

Preservation Hall opened its doors on June 10, 1961. It can trace its origins to a moment of serendipity when Allan and Sandra Jaffe found themselves captivated by a musical moment in the French Quarter. They had arrived a day earlier following a three-month stint in Mexico City as part of their extended honeymoon.

Allan had attended Valley Forge Military Academy, just outside of Philadelphia on a tuba scholarship, which had allowed him to leave his small town of Pottsville, Pa. Then, he enrolled at Wharton on a ROTC scholarship and ended up doing his basic training at Fort Polk, La.

Sandra grew up in Wynnefield, Pa., later graduating from Harcum College in 1958 with a degree in journalism and public relations.

Following their marriage, the pair opted to hit the road in a Volkswagen Karmann Ghia sports car before making any commitment to whatever might follow. Allan later stated, ‘’I was looking for a better life than working in a department store in Philadelphia.”

BEN JAFFE (TUBA/BASS): There are places on earth where you feel like you have to make a pilgrimage. And my parents felt like New Orleans was one of those places. They had also wanted to go to Mexico City and, after living for three months in the Zona Rosa, they were driving back from Mexico City to Philadelphia and stopped in New Orleans without an agenda or plan.

They rented a little apartment in the French Quarter because there weren’t a lot of hotels. Within 24 hours, they heard about somebody hosting a demonstration of a New Orleans jazz funeral in Jackson Square for a ladies auxiliary. At that time, white New Orleans had no idea what was going on musically within the Black community. Their only reference was that, maybe once or twice a year, a Black band would come and play at a Mardi Gras event or a college fraternity party or a dance. There was no interaction with the gospel music or jazz music of New Orleans. When I say that, I don’t mean what was happening on Bourbon St., I mean the real cultural music of the city, the music that was being performed for that community, by that community.

My parents walked into Jackson Square and my dad starts recognizing musicians in the band from records that he had. He recognized Percy Humphrey, Willie Humphrey, Jim Robinson, Cie Frazier, Kid Sheik Cola and others. This would be like going to Kinshasa and suddenly walking into Fela Kuti. I think he was in shock.

After this demonstration, they followed them back to Bill Russell’s record shop. He was one of the people who wrote the first book on jazz—at a time when it was seen as the devil’s music [1939’s Jazzmen] and created American Music Records, which is a very important label for New Orleans music. He documented musicians and music that would have never been documented. My parents peered through the window, then they walked across the street and into an art gallery where they heard music and met this guy Larry Bornstein from Chicago, who had been hosting jam sessions at his gallery space.

Within a day of meeting my parents, he gave them the keys to the place. They went back to Philadelphia one time to get all their stuff, and then they never left. That was the beginning of Preservation Hall.

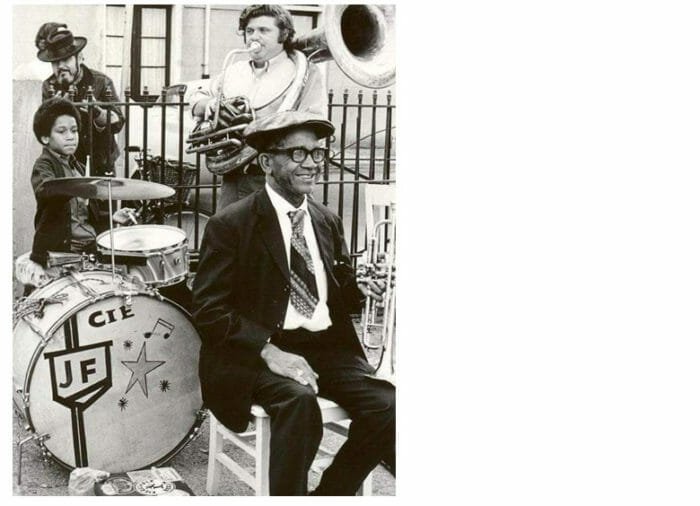

In 1961, many of the Hall’s performers could trace their lineage back to the origins of jazz in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. That is still true today. Charlie Gabriel’s family history even precedes this era. His great grandfather, who immigrated from Santo Domingo in 1856, was a bass player. His grandfather, a cornet player, led the National Orchestra jazz ensemble from 1913-1932.

CHARLIE GABRIEL (CLARINET): Music has been around me my entire life. It’s been the everyday conversation in my home since I opened my eyes up.

My dad played drums and saxophone, and his brothers played music, so it was natural for me and all my brothers. I had five brothers and all of them played music. My dad would decide what instrument he would teach us. At one point, he had three of my brothers playing trumpet: Leonard, Martin and August. Then my dad said, “Leonard, you can’t play trumpet no more, we have too many trumpet players.” So Leonard ended up playing trombone.

When I was young, my dad taught me and my first cousin Clarence Ford [who would work with David Bartholomew and become a longtime member of Fats Domino’s band]. Then, every Sunday, my dad would have us all play hymns together.

I first started playing music in New Orleans when I was 11 years old. I couldn’t solo but I could read and, sometimes, when people would call my dad and say, “Manny we got a job for you,” he’d say, “No, I’m already working, but you can take the kid.” I played with Kid Howard, Kid Sheik, Jim Robinson, T-Boy Remy and George Lewis on different jobs. So I was in the mix at an early age.

Generations of family musicians intertwined at Preservation Hall. Wendell Brunious was 6 years old when the venue opened and, starting in the late 1970s, he began playing trumpet at the Hall, which he continues to do today.

WENDELL BRUNIOUS (TRUMPET): My mother’s family, the Santiago family, came from the Philippines, and they were in that first wave of what people called jazz music. It was an extension of society music.

When I was a kid, my uncle Lester Santiago played at the Hall. My dad, John Brunious, was a great trumpet player. He didn’t play at the Hall because, in those days, he was too young. But I can remember him bringing me there when I was 9 or 10 years old to see my Uncle Lester playing with Albert Burbank, a great clarinet player, who used to sing in French through a megaphone.

I would also go there and sit on the floor and observe a lot of the older musicians, like Willie Humphrey, who was my daddy’s first music teacher. On Sundays, we’d see my Uncle Harold Dejan’s band, the Olympia Brass Band. We called him Uncle Harold but he was my dad’s first cousin. Sometimes Sweet Emma [Barrett] would sit in on piano and it was an experience that you couldn’t have anywhere else.

The Jaffes opened Preservation Hall at a time when segregation and racial discrimination predominated throughout the region. This continued even after the passage of 1964’s Civil Rights Act. However, from the very beginning, Preservation Hall was open to all musicians and audience members who sought to gather in the spirit of the sound.

BJ: Everything my parents knew about race in the South, they had read in the newspaper. This was their first time encountering anything like Jim Crow but as Jews they had experienced their own type of discrimination.

My parents were arrested on occasion and got shut down several times, but they were allowed to keep going because the authorities didn’t really understand what they were doing. This little enclave they were living in was sort of the outcast fringe. The community was surrounded by racism, but the French Quarter was often a protected little oasis from it all.

Preservation Hall became this center of extreme freedom. That, to me, is just as important—if not more important—than what my parents contributed to preserving a musical tradition. That musical tradition allowed them to celebrate this other freedom that was bigger than the music. This vibration brought people together and allowed them to overlook the differences that society wanted to impose on them.

RICKIE MONIE (PIANO): I used to play clarinet with the Olympia Brass Band and, when we had what we used to call a high-society gig—a sit-down gig—I played a piano. Some of the band played at Preservation Hall on Sunday nights, and our band leader invited me to come over as a visitor. This was about 1980. I met Willie Humphrey, Louis Nelson and, of course, Sweet Emma Barrett, who was the house pianist. When she became ill, I was asked to substitute in her place and I’ve been there ever since.

Preservation Hall was one of the first integrated places back in the ‘60s. It wasn’t popular for white musicians to play with Blacks way back then but Allan Jaffe’s focus was on the music and whoever was able to play the music; he didn’t worry about color. He treated us all equally.

If a musician needed anything, he’d do what he could to help. I remember one of the older gentlemen had a situation where his refrigerator went out and he told him: “Don’t worry about it, I have a refrigerator for you.” Then, he went out and bought a refrigerator. I remember that act of kindness.

It was the best gig in town, and probably the best paying gig in town. Allan Jaffe had a passion for three things: the musicians, the music and the business of music.

These three passions led Allan Jaffe to reassess his approach by the end of the Hall’s first decade.

BJ: In the beginning, my parents went door to door, found these musicians and brought them back. They provided them with a stage—a platform that would allow them to make a living.

However, my parents also told me that after the Civil Rights Act had passed, their intention was to close the Hall once the first generation of musicians who played there passed away—people like George Lewis, Papa John Joseph, Punch Miller and Jim Robinson.

They never thought about taking on the responsibility of protecting the tradition for the future. Instead, they were focused on supporting the musicians, who were playing a style of music as part of that tradition. They assumed that “once those musicians are gone, Preservation Hall will be gone.”

Nobody was there to tell my dad: “Jaffe, now that you’ve taken it this far, you have to take it to the next step, which is ensuring that it’s passed on to the next generation.”

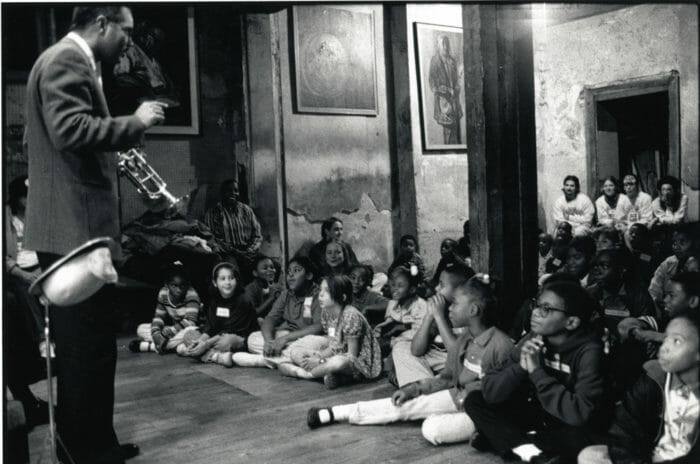

But toward the end of the 1960s—and on into the ‘70s—he recognized that he had a responsibility to recruit younger musicians and sometimes children who hadn’t even started playing music yet and bring them into this family. There are a lot of musicians today who are playing music because my dad would go pick them up when they were kids and bring them to the Hall so they could listen to the music and absorb the tradition.

It was falling out of favor and fading from the landscape because the young kids didn’t want to be like the old men out on the street. They wanted to be like Earth Wind & Fire. They wanted to be like The Jacksons.

Allan Jaffe’s efforts maintained a steady flow of young, capable musicians who could support the original members. By the time he died of cancer in March 1987, the Preservation Hall Jazz Band had traveled to Japan and made regular sold-out appearances at Carnegie Hall.

The Chicago Tribune wrote about Jaffe’s funeral procession, quoting a then 32-year-old Wendell Brunious, who said, “Naturally, when I was a teenager, I wanted to be contemporary like everyone else. But then I got interested in the old stuff. I found it to be more wholesome. I want the Hall to survive. I plan on playing there a while—at least till I’m 85.’’ The now 67-year-old Brunious adds, “I’m getting there,” before hailing Allan Jaffe as “a great man,” spotlighting his business acumen and commitment to the Hall.

At the time of his father’s passing, Ben had been preparing to enroll at Oberlin College’s Conservatory the next fall. He nearly changed his plans to attend a school closer to home until his mother convinced him to stay the course, enlisting her sister for assistance.

The younger Jaffe focused on upright bass at Oberlin, with the intent of pursuing a career in modern jazz. However, the week he graduated from college in 1993, his mother called to inform him that the musician who had taken his father’s place in the touring band wasn’t able to travel anymore. He made the swift decision to step into the role he still occupies today.

Ben faced a crisis early on as he experienced life on the road with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band.

BJ: I became concerned that we were becoming a caricature of ourselves. I began to feel like the musicians were starting to play what they thought the audiences wanted to hear.

There was this really important moment for me, where we played a concert with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. I was so excited about it, but when we got there, it wasn’t at all what I expected. I had grown up on Jimmy Blanton, Johnny Hodges and Paul Gonsalves. Their performances on so many records are fried into my brain. But when I heard the band, I was like, “Oh my God, these are all great musicians but they’re just called the Duke Ellington Orchestra. This is not the Duke Ellington Orchestra.” Then, I looked at us and I go, “Holy shit, what are we?”

It sent me on a creative tailspin. That’s when I realized that my responsibility was to make sure that this music had to be culturally and socially relevant or else Preservation Hall shouldn’t be around.

I was like, “Oh my God, my parents sort of altered the course of history” because some of the guys who were playing the songs didn’t grow up with a lot of the musical traditions. When you play “A Closer Walk With Thee,” it’s one thing to read it off a piece of paper. It’s another thing to be 9 years old and be marching in your first funeral, alongside other musicians who have been doing this 50 or 60 years and you’re playing as a member of the community for family members who have just experienced one of the greatest losses of their lives.

That’s what was confusing to me because every musician who started off playing at Preservation Hall had that cultural reference point. Now there was a new generation of musicians, and while some had that reference point, some did not.

I just knew that for us to continue, the music had to have the integrity of Ornette Coleman. It didn’t have to sound like Ornette Coleman. It didn’t have to dress like Ornette Coleman. It didn’t have to be any of that. It just had to mean something.

There were guys who left the band. I was never in it to prove to people that I was right but a lot of them were pissed at me. It’s taken me a long time to mend a lot of relationships.

Sometimes I’ve made decisions knowing that, no matter what I decide, I’m going to get hit. Someone in the press is going to hit me for it or someone in the community is going to call me about it. That’s the thing about New Orleans: You can’t run from anybody here. You’re going to see everybody every day. And I love that. I love that about the city because it means that you have to be able to back it up.

I’m just going to do what I know feels right and is respectful and honorable. I’ve always had people that I would bounce things off—people like Charlie Gabriel. He’ll tell me when I’m right or wrong about something. If he’s not feeling something, then we’ll move on. But he’s always so encouraging. He’ll say, “Benjy, you know, a smooth sea never made for a skilled sailor.” It helps me remember that this isn’t supposed to be easy.

August 29, 2005 was another day that reinforced that point.

RM: Talk about total devastation. I lived in East New Orleans—just a few blocks from the levy that held the lake back. We vacated the area before Katrina struck, but my neighbor who did stay was able to reach out his second story window and touch the water.

We had over eight feet of water in our house. I had a nine-foot concert grand in my home. I had a B3 organ, my clarinets and my other instruments in one room alone. I lost over $100,000 worth of musical equipment.

Eventually, I ended up in Baton Rouge, staying with my mother-in-law, my wife and my mother. We were there for 14 months.

BJ: None of us had ever ridden out a hurricane of that size before so we didn’t really have a reference, but we were all young and able-bodied. I was busy getting musicians out of New Orleans and preparing their houses for the storm.

Something that I now really appreciate about growing up in New Orleans is the respect that younger musicians give to older musicians. I didn’t realize that wasn’t common. I thought that was something that everybody did, but in New Orleans, you cut people’s lawns, you bring them groceries. You take them to the doctor, you do what needs to get done for your elders. Katrina took that to the extreme.

For example, I was helping a gentlemen named Narvin Kimball, who was 96 at that time. He was one of the original musicians to be part of the first Preservation Hall collective back in the early ‘60s. He stopped playing when he was 93 because of health issues and was pretty much unable to get out of bed by the time Katrina came, and his wife was legally blind. We got him safely out of New Orleans along with all of the musicians that I felt personally responsible for. There were some that we couldn’t convince to get out of town because there’s a community of people in New Orleans who feel, “I’m the captain of the ship and if it goes down, I’m going with it.” I guess I’m a little stubborn that way, too.

Preservation Hall is one of those frontline organizations in town where, when people are in distress or if there’s a need, they’ll reach out to us because they know we’ll be there.

I can remember receiving my very first text message after the storm came through. We still had analog flip phones, and they worked at midnight. If you went out into an open area, you might get a signal. I remember looking at my phone going, “What the hell is this?” It was a message from a trombone player who played at Preservation Hall. He was stranded with his family in Shreveport and nobody’s credit cards were working. Someone explained to me: “I think that’s this thing called a text message. It’s kind of like a beeper.” We couldn’t make any outgoing calls but what I realized was if he’s having that issue, then everybody’s having the issue.

So I realized I needed to get out of New Orleans to organize efforts to work on people’s relief. I saw the extent of the destruction in New Orleans and I knew firsthand that it was going to be months, if not years, before people were able to come back to the city.

The bridges leading out of New Orleans were barricaded because, as Jaffe recalls, “There was this hysteria that gangs of marauding, armed people in New Orleans were going to penetrate into the suburbs and cause mass destruction.” Fortunately, he happened to notice a military caravan moving through the French Quarter. He quickly drove behind the last car and followed them across the Mississippi River Bridge. After checking on Narvin Kimball in Baton Rouge, he stayed at a friend’s house in Lafayette for the night and then drove straight through to New York City.

BJ: I think the reason most people know me as a tuba player is because I lost my bass in Hurricane Katrina. I eventually made my way to New York, and the first show that we played was the Big Apple to the Big Easy event at Radio City Music Hall. I remember going down to 48th St. where all the music stores were, telling them my story, and one of them agreed to rent me a tuba.

So I began pushing this tuba down Broadway. It was in a big case and it started raining a little bit. My whole life has just turned upside down and people are screaming at me to get out of the way. I was at my wits end and I remember crying while I’m pushing this tuba case.

Then, I showed up and my band was there, and we were all seeing each other for the first time. I also met Dave Matthews, Tom Waits, John Mayer and Trey Anastasio. Everybody was like, “ Hey, man, we’re happy to be here tonight. Thank you for what you do.” That was a major moment for me where I was meeting people for the first time in this bigger music community who were acknowledging New Orleans. I had never really felt that love before.

Ben Jaffe has described his father as an “an adaptable business person who was a musician that could easily go back between the two sides of his brain.” Ben swiftly demonstrated that he can do the same, by establishing a thriving foundation to support displaced and out-of-work New Orleans musicians while also planning for the future of the Hall.

BJ: I could see it was going to be a few years before we were back to where people felt comfortable coming to the city and before we had the infrastructure to provide all the things that people need to live here—schools, hospitals, grocery stores, lights, electricity, plumbing. Looking at all of that, I knew that I had to put my energy into things that could generate funds for musicians. That turned out mainly to be my foundation and touring. That was when we really made an effort to get out there and new doors began to open to us.

My parents were always protective of the musical tradition, in the sense that they kept musicians at bay from sitting in with the band. They were like, “If you’re coming to hear the Preservation Hall Band, you’re coming to hear the band.” Their mindset was: “Do you go to Carnegie Hall to go sit in with the orchestra?” My parents always used Carnegie Hall as a cultural reference for the way that people should interact with the band and perceive the music. They held themselves to that standard.

I, on the other hand, was meeting lots of musicians who had the souls of New Orleans musicians, but they were as curious about what we did as I was curious about what they did. That’s when I really started going on this journey to understanding what collaboration means— because it’s not an idea that you come up with in an office. A real collaboration is when you’re sitting with somebody having what Charlie Gabriel calls a musical conversation. You’re talking about things, you’re seeing things, you’re learning from each other and you’re discovering something about yourself through that other person.

We had always toured. The band had been on the road since the early ‘60s but now it was, “Let’s go to Bonnaroo. Let’s go to Coachella. Let’s go play with this person. Let’s go play with that person. Let’s go open for My Morning Jacket.” I had never really considered that this could happen for us, although I dreamed it was possible. The Grateful Dead occasionally had Preservation Hall open for them back in the day. So I thought, “This is not a new idea. It’s something that is cyclical and has come back again for us.”

RM: I thought that My Morning Jacket was the type of rock band that would be breaking guitars onstage and everything. So when we first sat in rehearsals, I asked them about it and they told me that they weren’t that kind of band. There also wasn’t any of that weed smoking and all the stuff you hear about rock bands. They told me they had to stay healthy because of the energy that they use onstage.

But, one night in rehearsal, they said, “Since you asked about breaking a guitar, we went out and bought one. We want you to come out on stage and break it.” They had bought it in a pawn shop and taken a saw to the back so that it would break apart easily.

I walked out there in a suit and a tie in the middle of the concert with the guitar. Then I smashed it, stomped on it and started playing with the dangling strings. The crowd went crazy, man. After the concert, all of the guys in My Morning Jacket signed that guitar and gave it to me. It’s one of my prize pieces of art.

Preservation Hall both survived, and even thrived, in this new era. The building itself, which dates back to the early 19th century, had experienced moderate damage during Katrina, since the French Quarter is the oldest section of New Orleans built on the highest ground. However, as Jaffe notes, “a small hole in your roof that goes unfixed for two months can wreak havoc.”

The Preservation Hall Jazz Band continued to travel and collaborate, including a well-received record (American Legacies) and tour with the Del McCoury Band in 2011. The PHJB then released its first album of all-original material, That’s It! in 2013, followed by So It Is in 2017—both of which built on the palette of music that has informed the Hall. The 2019 film A Tuba to Cuba and its accompanying soundtrack traced some of these musical roots.

New musicians continued to enter the fold, such as trumpet player Branden Lewis, who arrived in New Orleans on New Year’s Day 2012. Although Lewis was a Los Angeles native, he had deep familial ties, as his grandfather, James Victor Lewis, had led a renowned local R&B group Li’l Millet & His Creoles before relocating to LA in the early ‘60s.

BRANDEN LEWIS (TRUMPET): I moved here with a one-way ticket, my backpack and my trumpet. I was classically trained but I had no idea how to improvise. My first interaction with members of the Hall was getting lessons with Wendell Brunious right outside Hotel Monteleone on Wendell’s break. He grabbed a piece of receipt from the bar, borrowed a pen from the bartender and he gave me enough things to work on to keep me busy for a while.

My first interaction with the Hall was seeing Shannon Powell, Freddie Lonzo and Wendell play. I’d seen some of the transplant bands on Frenchmen St. that skew a little bit further into the Dixieland side of the music and they sounded corny to me, for lack of a better word. But I was like, “Wow, these people are representing this music” and you could never call it corny.

When I later joined the band, Charlie was three times older than me. I was 27 and he was 84. In some ways, I think I keep them young and they give me the wisdom of being on the road, like we haven’t eaten fast food once. I also stopped smoking cigarettes. When I met Charlie, he was like, “Hey, man, do whatever, but like, just so you know, literally everybody I know that used to smoke cigarettes has checked out of life at this point.” I quit smoking cigarettes that week.

I didn’t know about Preservation Hall before I got here. But once I found out, I was like, “Damn, that’s what’s up!” It was pretty amazing for me to witness the music for the first time. Not only that, but there would be a line outside that went down the block, sometimes two blocks, every single night of the week.

All of this changed in March 2020 with COVID.

BJ: What COVID proved to us again is that New Orleans is a very small city. We’re like 375,000 people, but we act like we’re like 2 million. If you think about New Orleans, 375,000 is smaller than Tulsa, Okla. As a city, we actually can’t support a lot of the things that make New Orleans, New Orleans—the music venues, the restaurants, the concert halls, Jazz Fest. All of those things are supported because we have this constant flow of people coming through the city.

Every venue operator had to make a decision that was going to impact musicians, ticket holders and employees, as well as their own families. I don’t know anybody who said, “I’m going to get into the music business because I want to make a ton of money.” You get into it because it’s all you can do and you’ve been called to do it.

I made the decision early to close the Hall. It was hard because I know how thin our margins are at Preservation Hall. I also knew the impact it was going to have on my family, emotionally and financially. My wife is also our accountant and CFO and I remember sitting there, holding her, just feeling overwhelmed with sadness for my community and for everyone else as well.

Then, I woke up in the middle of the night and I was like, “Fuck this shit.” I pulled out one of those dry-erase boards and I wrote down: “This is where we are right now. This is where we need to be in a week. This is where we have to be in a month. This is where we’re going to be in six months. This is where we’re going to be a year from now.”

I fell back on everything I had learned from Katrina. And that was act quickly, act fast because the needs are going to come fast—just like that text message from Shreveport. I knew that if I opened up my email there would be a dozen messages from people that said, “I don’t know what to do. I don’t have anything.” So I knew that, immediately, we had to shift our Foundation’s primary function to emergency relief.

By the end of that day, we were in communication with every musician that plays at Preservation Hall. We created an emergency database and, within a week of Preservation Hall closing its doors, we were able to begin financially supporting the musicians, the culture bearers—not just the spine, but the blood and heart of New Orleans.

WB: This music is such an important part of our culture, and to have that in limbo was really tough. I actually had a bout of COVID early on. I had been wondering why I didn’t have any energy. Then later on, even after I got vaccinated, I tested positive for COVID at one point, although I didn’t feel so bad. But to be without the music was like taking one of your children away.

BL: COVID has been devastating for the whole community. It’s particularly unfortunate what it’s done to someone like Charlie. All he wants to do is play music with other people and, for a long while, he couldn’t do that.

CG: Since I was confined to the house for a year and a half, I said, “I’m gonna make this be constructive time.” So I took myself to the piano because I couldn’t go anywhere. I sat there and I really advanced my skills.

RM: My wife had been on my case for years to do a CD, and I would say to her: “I’m traveling, doing like 200 concerts a year. I just don’t have the time.” Then, when COVID hit, I said, “Well, I guess I got a lot of time now.” So I made a CD titled Inspirational Melodies. It’s religious music. My friend Bridget Bazile is an opera singer and sang two songs. The rest of the CD is me on the B3 organ. Then I got brave and entered it for a Grammy and it was nominated. I didn’t make it to the last round, but at least I’ve got that little notoriety.

WB: I have these two stage plays I had written a while back. There’s a play where a couple of sisters are in the Baptist choir and they attend a Baptist choir convention here in New Orleans and all this stuff happens. Well, what I did during COVID was write a whole soundtrack. For instance, one of the girls really likes Billie Holiday and I had to write some of those of Billie Holiday-ish tragic songs. I hope to get it out one day. So with the lemons, I made lemonade.

BJ: I committed myself to certain things that I had wanted to learn how to do like production work in the studio and how to use certain software.

My house is around the corner from my studio, so eventually, Charlie Gabriel started coming over and we began rehearsing, practicing, recording and getting our lives back on track. We’re jazz musicians, we have to practice. We’ve spent years of our lives getting to the place where we’re able to do what we do.

Whenever somebody’s name popped into my head or into my thoughts, I also made a point to reach out to them. A lot of times life can just be like a backstage hang, where you’re high-fiving and congratulating and hugging. But to actually sit down and have a meaningful conversation with somebody—man, this has been a year and a half of the most beautiful, heartfelt, important conversations that I’ve had with people I’ve grown up with and known my whole life. I couldn’t imagine any of those conversations ever happening if it were not for COVID. That’s another one of those emotional juxtapositions that’s so extreme.

Preservation Hall finally reopened on June 10, 2021, exactly 60 years after Allan and Sandra Jaffe had first welcomed the community inside.

However, just as momentum was picking up again, on another anniversary, August 29, 2021—16 years to the date that Katrina had decimated the city—Hurricane Ida made landfall, closing the doors of the Hall for another two-and-a-half weeks.

RM: It was like a flashback of Katrina. I looked out my window and saw one tree twisting with a type of motion I had never seen in my life.

So here we are again. Now there are no conventions or tourists coming into town for two reasons: COVID-19 and Ida. A lot of restaurants had to close because of roof damage and water damage. New Orleans looks like blue-tarp city.

CG: We have no control over what the weather is going to be. The way New Orleans is situated with all the water around, there’s no telling what we may have to endure. Now, I don’t want to sound foolish, but God don’t give you no more than what you can handle.

BJ: The fact that it happened on the anniversary of Katrina sent my wife and I into a sort of emotional tailspin. But here we are.

And again, immediately, we went into relief mode because, even during COVID, the mantra that we kept talking about in the organization was: “It’s COVID, it’s Katrina. What’s the next one going to be?” There’s going to be a next one, so how can we prepare for that? We don’t know what it’s going to be or when it’s going to be, or how big it’s going to be. But when it does come, how can we be prepared to navigate it?

What I do know is that, whatever happens, we’re going to work through it together. Something I really believe is that community is not a noun. A lot of words that people use as nouns become verbs in New Orleans. Community is a verb. Culture is a verb. Jazz music is a verb. They’re living action.