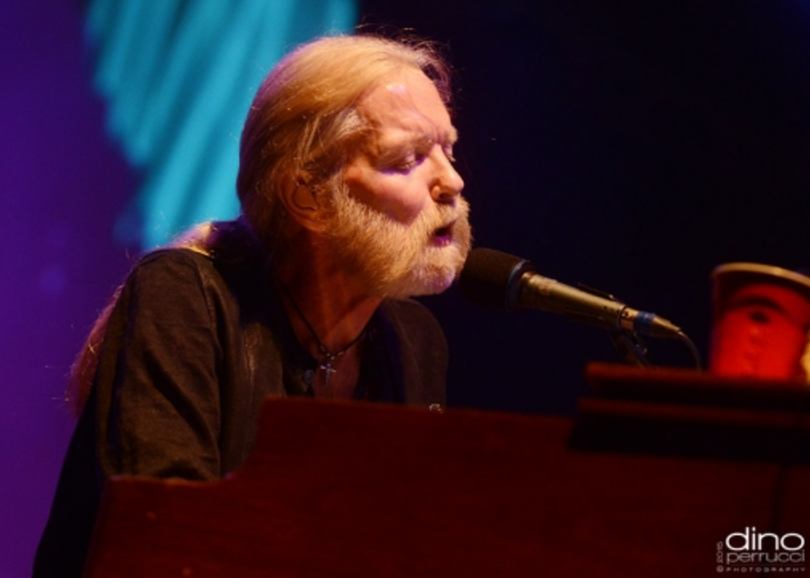

Old Before My Time: A Conversation with Gregg Allman

In honor of Gregg Allman’s 69th birthday, we revisit this feature that ran in our special tribute issue of the magazine after his passing.

This previously unpublished interview with Gregg Allman took place in March 2003 in the midst of the Allman Brothers Band’s annual Beacon Theatre run. The group had just released Hittin’ the Note, their first new studio album in nine years and only such effort following the departure of Dickey Betts.

Warren Haynes produced Hittin’ the Note, along with Michael Barbiero. This was all set in motion back in 2001 when Warren rejoined the Brothers [after leaving in 1997 to focus on Gov’t Mule with Allen Woody]. Talk about your role in inviting him back into the fold.

I was sent to military school when I was real young, and people get different things out of it. I came out of there not liking confrontation. What had happened was, while the band had once been quite democratic and everybody was wide open, it was becoming a dictatorship, and I was fully ready to quit. Then things changed [when Betts left in May 2000], but we began all these days of arbitration in which I was flying to New York again and again.

I wasn’t sure where all of this was going to lead or really even where I wanted it to go. That’s when I decided it was the right time to give Warren a call. It had been a while since Woody had passed away. I didn’t know what he was doing so I invited him to come down, play a little bit and see how it turned out. I told him, “If you don’t like it, no problem…” I didn’t tell him this, but my feeling at the time was that if it didn’t work out, I might have just said, “To hell with it.”

The new album features a number of new originals that you wrote with Warren. Can you talk about the process of writing those songs with him?

There are as many different ways to do it as there are songs. It has to feel right, though. That’s where it all starts. Oteil [Burbridge] came to my house and we tried to write some songs a year or two ago because we were damn sure in dire need, but we just couldn’t make it work. I didn’t know him well enough, or it was too soon or something. We tried but nothing really came of it. That sort of shows you that you can’t predict it.

That little girl who took the five Grammys [Norah Jones], I’m crazy about her. I think they might have cut that album in her garage—that’s killer. And if that ain’t raw talent, then I don’t know what is. But it’s always hard to predict. People can go into something with the best of intentions and it still might not work out. That’s the story of my life, brother. [Laughs.]

With Warren, my first question for him was, “Where do you want to write—your house or mine?” Because we wanted to feel comfortable. That’s part of it. You want to feel comfortable—just not too comfortable… [Laughs.]

So Warren came to my house in Savannah. I live out on a bayou in the country, where you can’t hear any distractions other than maybe a couple of angry squirrels. [Laughs.] The way we started was with me at the piano, just sitting there finding my way. Now, sometimes, nothing gets done like that, but I feel safe with Warren because he has the same tastes as I do. That’s probably why we play so well together—he likes what I like and he doesn’t like what I don’t and those are long-formed opinions. We’re kindred spirits.

When Warren showed up, he came right off the road and he was dog tired—he was horizontal for almost a day and then, he woke up and we got after it. We started “Desdemona” in the morning and we finished it after lunch, with me at the piano and Warren sitting there with a notebook where he had written down all sorts of ideas. Again, we have that special connection, and we have that trust, so it was real easy for us.

That evening, I picked up my [acoustic] guitar and we started the music to what became “Old Before My Time,” but it got really late, so I went on to bed. He stayed up and walked over to my piano, where he saw something on the pad where I had been working on some lyrical ideas back at breakfast. He used the music we had been working on, wrote a bridge and slammed another verse on there while I was asleep—and there it was. When he showed it to me in the morning, I wasn’t sure about it, and it took a while for it to grow on me because I had plans for that. [Laughs.] But it’s really about trust.

A real magic thing happens when we get together to do some writing. He’s a really fine guitar player and he’s a chord king—“Do you need a bizarre one or a regular ol’ everyday one?” Plus, Warren’s a singer. He understands about phrasing the music with the vocals and the melody line—what ratio the music should have to the melody line.

He’s such a sweetheart and very intelligent and very learned. It all just laid down perfect like it was planned. I had this renewed energy. I physically felt younger— whenever you have new songs and they’re really kickass, you suddenly shed three or four years—or maybe 10. [Laughs.] We’re talking about doing an acoustic tour and it still might happen.

In terms of your relationship with Warren, people sometimes forget that after Warren and Woody left the band, you sat in with them later that fall.

You have to understand that there weren’t hard feelings between myself and Warren. A lot of that comes from the outside, where people don’t know what they don’t know. I don’t concern myself with any of that outside negative shit because a band can usually handle that together, and it’s nothing more than swatting a fly. The problem is when shit starts to happen inside a band—that’s what breaks up bands. But with Warren and Woody, there wasn’t really so much of that. They just wanted to go.

After they left, they invited me out to see a show at The Fillmore in San Francisco. We caught up in the dressing room, and I watched from the balcony. Then, before the encore, they asked me to come out and play, so I did. I’ll always remember the people in the front row had their mouths open—they couldn’t believe it. But it’s never like people think it is.

Looking back, why did you feel the time was right to make another Allman Brothers Band record?

Well, that’s a good question. It’s a question that Warren had for me because when I told him what I had in mind, he tried to talk me out of it. [Laughs.] Well, maybe for a minute he did—his point was that, if we were going to put out another Allman Brothers Band album, it would have to be something that would hold up against all the previous Allman Brothers Band albums, especially those that we cut when my brother was around.

I took that as a challenge. I’m in the mood to take on challenges these days. This is another era for me: I’m rested, my head is clean and I can even sleep at night. I used to have these nightmares, particularly when I would come off whatever I was on. The dreams would store up in me and then, they’d all come out at once— and not in a pleasant way. When I was on whatever I was on, I wasn’t even really asleep; I was in the gamma level of sleep, in which I was passed out. But now I have regular nice dreams and, when I wake up, I actually feel rested. That helps in everything you’re doing from writing songs to singing and playing.

Then, when it came time to record, we were all really communicating and it felt like a dark cloud had been lifted. This was a very different experience from what we’d done in the recent past, and it’s probably my favorite one since when we recorded with my brother. We had enough time to record, but not too much time. That’s when you can get yourself in trouble. [Laughs.]

On our first record, they handed us $75,000, led us over to 1841 Broadway, gave us one day shy of two weeks and said, “We want to see something.” We’d been in a demo studio but never in big one like that. I’ve always said I’d like to go back and cut that record over.

After that one though, we always had enough time to work on the records—probably too much time. That’s when I learned not to go to the mixdowns. I don’t go to them anymore because, when I went to the first one, everybody had a knob in their hand and they were pushing it up and up. Finally, everybody had to stop and push them all back down. That’s idiocy.

Can you talk about the name of the record?

The next big question with any album is what are we going to name it? When you’re naming an album, it’s like naming a hound dog and that’s never easy because, after Spot, all the good names have been taken. [Laughs.]

We were going to use one of the lyrics; we were going to call it Victory Dance [after a line that appears in “Old Before My Time”] but then we were in the middle of the arbitration thing, and we didn’t want to start any crap. That’s when Butchie [Trucks] said, “Hell, let’s call it the obvious—we’ve never used Hittin’ the Note.” It was an expression of Berry Oakley’s that means in the pocket, on top of it—everybody’s biorhythms are perfect, everybody’s hitting the note at the same time. When you went and saw a band and you came back, the rest of the guys would ask if everybody was hitting the note.

What are your favorite moments on the album?

My favorite part of the record is what isn’t on there. There isn’t a clunker on the set. In the past, our records always had that one track—the one where you just shake your head. That’s the track where, if you’re playing the album for a friend, you start talking louder hoping that nobody will be paying attention—or you hope a train will come plowing by the house or maybe plowing into the house, just for a little distraction. [Laughs.] But with Hittin’ the Note, there is no distraction needed. You can print that.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Summer Jam [the Allman Brothers’ triple bill with the Grateful Dead and The Band at the Watkins Glen Grand Prix raceway on 7/28/73, which once held the Guinness Book of World Records title for “largest audience at a pop festival”]. What are your memories of that show?

I can appreciate festivals but, sometimes, they can be tough for us if we have to play in the sunshine. You can’t play blues in the sunshine. Try to play “Stormy Monday” out in a damn field with the damn sun shining—there’s not much mood out there.

But Watkins Glen started out really scary because I had just gotten out of the hospital after having my gallbladder taken out and, when you have surgery like that, you hurt all over—even your damn earlobes hurt and you’re not in the mood to talk to anybody. You’re in no mood to have a good time. Then, I got into this helicopter and the pilot was real drunk—he scared the hell out of me. That wasn’t a good day for me, but I sure am glad those people came out and it sure as hell was incredible that, with three bands, you can get that many people—I think it was 683,420-something. It was a bunch of ‘em. To give you an idea, it took three sound companies—who made these monoliths of speakers out in the crowd—because if you hadn’t had those towers, after we hit our last note, I could have packed my guitar, wiped off and shut the case before the last guy in the last row heard the last note.

The Grateful Dead were on that bill, which reminds me of the time that you expressed some exasperation with the nature of the improvisation in your band. There was an occasion in June 2000 where you had some words for Oteil Burbridge, Derek Trucks and Jimmy Herring after hearing them on “Mountain Jam.”

I just told them, “We’re playing Allman Brothers music here.” We’re not some other band. Things can get anticlimactic if it’s too much of the same. It takes away from what you’ve already done, like painting with too much red. Do you remember the Blues Magoos? We met them back in the day and the guitar player was really good, but he loved that psychedelic beating of the guitar and, to me, that is just buffoonery.

Derek does all right. It’s just that, in my own opinion, what they were doing in particular places kind of threw me off. [Laughs.] But the thing is, we don’t want anybody to copy what someone else in this band had once done, lick for lick. That would sound totally contrived. We want everyone to bring their own expertise to what they’ve been hearing all these years.

But it’s important to remember: We’re not one of those little jambands. We’re not a jamband, we’re a band that jams. We’re a progressive-blues-jazz-fusion band now that there’s no more country.

You’re currently in the middle of another Beacon Theatre run. Do you have any rituals that you go through on the day of a gig?

Well, I don’t know if I’d quite call this a ritual but, starting at around 4:30 p.m., I start to feel afraid that I’m not going to be good enough. [Laughs.] People call it stage fright, and that’s basically what it is—you feel like you’re inadequate. But when everything’s ready and the energy from the people hits you and the downbeat hits, then those symptoms you had are so far away.

Sometimes, during the break in the middle, you can lose some of your edge, but you’ve got to go out there and take over. There’s no frontman in this band. At one time, they asked me to do that and I said, “Absolutely not.” So I have to take over in my own particular way.

You started playing the Beacon back in 1989, and it’s long since become a tradition. What do you think accounts for that?

It’s the Fillmore. It feels exactly like it; you just don’t have all the flowers and incense. I loved those days. It even sounds like the Fillmore—it’s got one more balcony, but then, I always thought the Fillmore could be a tiny bit larger.

There’s also something special about the chemistry between the Brothers and the people of New York. I can’t quite put my finger on it, but a lot of it is that we’re not bullshitters and neither are they. They want something real, not something that’s been watered down.

Another thing I should say—and this is about the band not the Beacon, but it applies to the Beacon in a major way— is that I’m really happy with the decibel level onstage. The volume has come way down so we can all hear each other better. I can promise you that Jaimoe is with me on that one—it’s something we’ve been talking about for years.

Now, the other thing I would like to do—and I’m not sure if I have any takers—is I’d like the shows to be shorter. At times, I think that what we’re doing can be overkill. I’ve always felt that way. Two hours should be the max. For years, I’ve felt it was too loud and too long. We’re halfway there… [Laughs.]

On the second night of this year’s Beacon run, you opened the encore with “Layla,” which took everyone by surprise in the best way possible way. [Duane Allman supplied the slide work on the original studio version by Derek and the Dominos.] How did that come about?

My initial reaction was forget about me singing it. That’s up there, bro—way up there. [Warren Haynes sang lead on the version the ABB debuted on 3/14/03.] When Clapton was on HBO and he did that song, he used three guys, counting himself, playing Strat and singing.

I was there when they recorded it; I watched it. Derek and the Dominos were down in Miami while all the Allman Brothers were there [in August 1970]. Tommy [Dowd] invited the Brothers to visit them in the studio, and there was one night with a little bit of a jam, and then everybody left. But I stayed down there with my brother because he was playing. Back then, Eric wasn’t playing slide. The whole thing was very enlightening— I learned a lot—plus, it was incredibly entertaining.

You’ve said that the new material has energized you. What do you see as the future of the ABB?

When Robbie Robertson left The Band, I couldn’t understand it, but I can today. It wasn’t anything personal; he just got tired. He’d played every place in the world and he just wanted to be with his kids.

But I have this renewed energy. That’s what happens whenever you have new songs and they really kick ass. When you’ve been everywhere and heard so much and played so much, it takes a lot to blow your dress up like when you first heard Hendrix. I don’t know how many years are left in the Allman Brothers; hopefully, we’ll always play. Les Paul plays every Monday night at this club in New York. I would like it to come out kind of like that. He’s in his 80s and he still hits it.

It’s such a blessed thing to get up there and watch those people’s faces, and play on and see them absorb this stuff. I’m not getting born again on you but it’s such a blessing— it really is. I approach each concert like it’s the last one because it very well could be. I go at it like it’s the last one I’ll have the privilege of playing because I love to play, and I’m so thankful to God that he picked me to play.