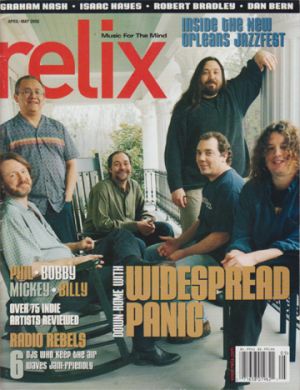

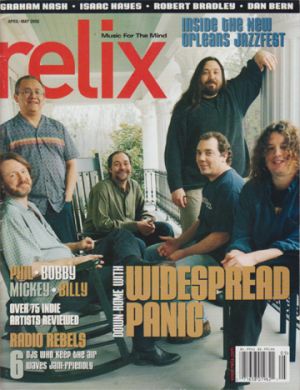

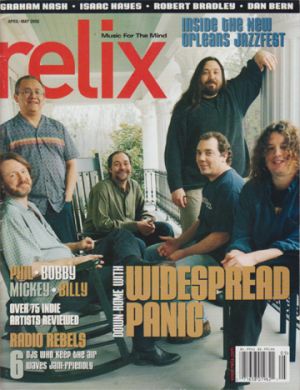

Lit Fuse, Got Away- Life’s Been Grand for Widespread Panic (Relix Revisited)

We’re less than two weeks away from Widespread Panic spring tour, the group’s first such series of dates in 14 months. So with many of you in the mood for some Panic, we share this cover story from the April-May 2002 issue of Relix.

It’s a career profile that echoes strategies employed by the Grateful Dead, who forced their first label, Warner Brothers, to build its identity around the band, and whose breakthrough albums were live releases that documented the numinous experience of the group’s live interaction with the audience. That interaction eventually allowed the band to bypass the institutional bureaucracy of the record industry and deal directly with its snowballing fan network.

You have to care more about making music than money to pull this off, at least in the short run, but Widespread Panic is part of a new generation of bands whose collective audience base requires a content-over-style approach to its entertainment. Their success style is not like Almost Famous, that comically earnest prequel to Spinal Tap. It’s about musicians who get to “do what I want to get paid” as Tom Waits says, which really is the ultimate revenge if you’re smart enough to recognize it.

That’s why the atmosphere is positively sunny on this rain-swept winter afternoon in Athens, Georgia. The boys are assembled in the basement of Brown Cat Inc., their spacious, unpretentious warehouse headquarters in an industrial court on the edge of town. This basement clubhouse could pass for any number of similar hangouts where a group of buddies lay back in overstuffed sofa chairs around an old coffee table. The garage ware lying around is not just any old junk – it’s an informal archive of Widespread Panic memorabilia. Draped across the wall behind the chairs is the black magician’s costume worn by guitarist Michael Houser for the legendary 1997 Halloween show at Lakefront Arena in New Orleans. Cardboard boxes full of band merchandise are piled up in the front corner, while the far end of the room is a jumble of spooky constructions and costumes, the remains of set designs from other Halloween shows.

The members of the band are in great moods, and why not? After years of struggling they are on a roll, coming off their best year ever in terms of ticket sales, with a best-selling DVD on the market, a film in the works and a three-CD live set ready to go. They’re having a get together on their home turf during a break from touring and recording, and it is easy to see from their interactions that they’re not just a band members but close friends. They think collectively, referencing private jokes and common experiences remembered by a single word or phrase, and they tend to finish each other’s sentences.

The band’s group dynamic reflects this tight bond. John Bell carries an authority born out of the others’ respect for his humility. As the main lyricist and frontman, he could easily be a dominant voice but in conversation he’s more of a listener. When he does speak his words carry weight, but he’s careful about forcing his opinion on others.

Musically, Houser is the band’s main voice, but it’s just the opposite in conversation, where he’s quiet and soft-spoken. When he says something the others hang on every word. Yet Houser is a brilliant wit and his pithy one-liners can send the others into paroxysms of laughter.

Bassist Dave Schools is the most loquacious members of the band and a passionate rock historian who seems most completely to understand Widespread Panic’s place in the context of its progenitors and offspring.

The affable drummer Todd Nance is a social fulcrum balancing the group’s wide range of interests, good-natured and jocular without being overbearing. Percussionist Domingo “Sunny” Oritz is a burst of light, an effervescent part of the group interaction that seems eternally pleased to have such good friends to work with. John “JoJo” Hermann, the last piece of the Panic puzzle when he sits at the keyboards, marvels at the fact that he’s been with the band for ten years.

MANY OF THEM WEPT

Back in 1985, popular music was even more mind-numbingly empty than usual, thanks to the efforts of MTV to turn the one-hit fashion wonders of the British New Romantics movement into the 1980s version of Hollywood. Major label deals were assigned by screen tests, not demos. If you were a college-going music lover in Athens, Georgia, where Houser, Bell and Schools met and began playing together, you ignored the highest profile popular music, listened to the local groups on the scene instead of formed your own band.

“It you were into music you had to move away from radio basically,” says Houser.

‘We were listening to Warren Zevon and R.E.M., the Grateful Dead," Bell recalls. “There was a lot of local stuff that was cooking. The atmosphere was really great. Athens had a lot of bands.”

“It wasn’t a copycat scene,” adds Schools. “If you ask someone what the golden age of Athens music was they would probably say Pylon, Nutcracker and R.E.M., and none of those bands sound the same.”

“When Mike and I first started playing together,” Bell notes, “we started out playing two-chord songs, throwing it around back and forth; we could change tempo a little, then improvisation started in. Dave fit in, but it took a while for us to gel.”

The band started having fun playing those two or three-chord songs and a few originals, but the audiences didn’t always share the enthusiasm.

“At one gig the guy who booked us told Mike, ‘Have you considered delivering pizza for a living?’” Schools recalls.

“One of my dearest friends told me that he hoped I wasn’t playing music for a living,” says Houser. “And he was the one that hired us. I think we had two guys on either side of the stage playing congas, just banging away, with JB and the rest of us in the middle.”

“We terrorized many drummers,” Houser deadpans, putting the band in stitches. “Before Todd came along we could change tempos and we knew where we were going but they would be thrown”

“Many of them wept,” laughs Schools.

“But when Todd first played with us he just did it like nothing had happened,” Houser says. “He fit in naturally.”

“Todd also provided us with the background we wanted,” adds Schools. “At least there was someone who would draw the line at some point: ‘Hey, this song has now approached the 28-minute mark.” "

Houser had known Todd since high school. “Todd and I had a mutual friend who introduced us,” says Houser. “and we played in a kind of basement band back then. I came here to college, and I didn’t see him for a long time. Like I said, we just had the worst luck with drummers; they all wanted to do something else. We had a gig coming up so I told the guys about Todd. I called his home and talked to his mom, and she told me he was in Atlanta and I thought ‘great’ because I thought he was three hours away and it turns out he was only an hour away. I called him up.”

“I came up and listened to a tape they had made,” Nance recalls, “then I came back for a rehearsal and the only one there was Dave.”

“I didn’t have a car or I would have left, too,” Schools chuckles.

“We all lived in this nasty house,” Houser says. “We had a phone for about two weeks, then gradually the electricity and heat and finally the water got shut off. We had to make our own candles for light. We used to look forward to going on the road because there would be heat and water and food, television.”

The Uptown Lounge was dark on Monday nights and the owner let Widespread Panic take over the night, allowing the band what amounted to vital rehearsal time. “We got paid two pitchers of draught beer and usually had a bill at the end of the night,” says Bell.

“I think we had to write a check so we could leave the bar,” jokes Schools. Schools made tapes of the Uptown shows, which are circulating somewhere out there.

“Early on I made a lot of cassettes so we could listen back to what we were doing,” he says. “I’d lost them for years and then I found a whole garbage bag full of them. All they said on ‘em was ‘Uptown Lounge Monday night.’ The way the songs would develop is we’d play them for several Mondays as a jam. Then the next Monday there would be a verse. Then the Monday after that there would be a bridge. You’ll hear us rehearing songs in the kitchen and then that tape will run out and there’ll be 15 minutes of JB dictating his class notes.”

“I wanted to learn in my sleep,” Bell explains.

“The funniest sight ever was when Todd brought his drums up and he had been rehearing somewhere where he couldn’t play loudly, so he had carpet attached to the inside of his drum heads,” Schools laughs.

“JB had an amplifier speaker that the cone had torn out of and he was using playing cards with rolling papers taped across the front,” says Nance. “Our first lighting rig, JB went and got these institutional-sized cans and put light bulbs inside the cans.”

One night at the Uptown percussionist Domingo “Sunny” Ortiz walked into the club when Widespread Panic was playing. By the time he had walked out he was in the band.

“I had just driven 16 hours and the club owner says, ‘You’ve got to play with these guys’” he recalls. “I was tired and I said ‘I’ll listen to them but I won’t play with them.’ The next thing I know I’m up on stage having a great time. I thought these cats were great because they were improvising, which of course I was already accustomed to. It was hip.”

“He drove into town, got out of his car, walked into the club and he was in the band,” says Nance.

“We asked him ‘You wanna go on the road?’” Bell chimes in.

“He found us all later outside the club peering into his car looking at his drums,” Houser laughs.

“When I heard the music before I got up onstage, I dug it because as a percussionist I could hear all the spaces in the music where I could improvise,” says Ortiz. “It was a different style of music, not like a Top 40 cover band. I loved it.”

JUST GO OUT AND DO WHAT YOU DO

Widespread slowly built its reputation around town and was soon associated with the Athens music scene when they hit the road, the first of several unwanted labels they’ve been tagged with over the years.

“When we first started playing gigs we were Widespread Panic from Athens, Georgia,” says Bell. “When we were on the road a bunch of folks would come up to see us expecting to hear some R.E.M. People were expecting some punk or angst and we said, ‘We’re just here for the sandwiches.’”

“There was a lot of anti-R.E.M. backlash among Athens bands,” Schools points out. “There was one band that was detuned guitars and live arc welding on stage. There was a band called Wall of Shit. By the time there’s a national perception of a regional sound something completely different is happening there. We came out of a club era when reggae was really big – three nights out of five there as a reggae band. There were a number of ‘70s cover bands doing Traffic songs and psychedelic things.”

Widespread Panic’s producer John Keane was in a cover band called Strawberry Flats. “They wore paisley and played Beatles tunes and Deep Purple tunes,” says Schools. “It was a strange time. The hair bands hadn’t taken over yet. It was before alternative was a term. There was a lot of different stuff happening and it was annoying to come into town and be described in any way.”

Widespread was also building musical bridges to other local groups. Tinsley Ellis, guitarist with the Athens-based Heartfixers, heard about Widespread and came to Athens to jam with them.

“Tinsley put us together with Michael Rothschild and Landslide, which is where we met Bruce Hampton,” says Schools. “He helped us a lot, told us what clubs to try to book ourselves in. Tinsley’s brother told him about us and he showed up one night and asked if he could jam with us after the show. We told him we didn’t even take our equipment home with us, but a friend of ours told us, ‘Hey you should play with this guy, he’s good.’ So we took our equipment back to the house, set it up and started jamming at four in the morning with Tinsley. Bruce started showing up at shows. He was like this crazy guy who would get onstage with us and do ‘Love Light.’”

“And we might go into another tune,” Bell chortles, “and he’d still be singing ‘Love Light.’ Then we realized he was with Landslide Records. He actually hand-delivered our first CDs. When we first put our Space Wrangler it was on vinyl. That was right on the cusp of the CD era.”

Ellis hooked them up with Michael Rothschild, whose indie label Landslide had released albums by the Heartfixers and Col. Bruce Hampton. “We gave Michael a tape of the studio material on one side and some live stuff on the other side,” says Bell. "We weren’t looking to do anything with him, we just asked ‘What do you think of this?’ He actually got a little proactive, saying you can’t release this live stuff. We wanted to put a record together but we didn’t know what we were doing

“Michael said, ‘If you have a cover tune that’s short and catchy, put it on there,’ which was a nice way of saying, ‘You need a hit.” And don’t ever play ‘Nights in White Satin’ again. He put it out for us and we thought it was pretty good."

Widespread Panic began touring and found some support for their brand of music. “The first time we played San Francisco we were kind of shocked because due to the grapevine of live tapes, people knew the words to some of our songs, which was amazing,” says Schools. “We played the Full Moon Saloon on Haight Street. We used to have this rule that wouldn’t go onstage until the crowd outnumbers the band. There were people there who knew or stuff from live tapes. Little things like that can get you to the next gig. Or at the Chukker in Tuscaloosa where there was nobody but us and the bartenders and they pulled out these lounge chairs to watch us.”

After several years of scuffling around the country, Widespread came up with a brainstorm of an idea: pooling resources with other like-minded indie bands to a do-it-yourself tour. HORDE (Horizons of Rock Developing Everywhere) was born, and suddenly Widespread Panic was part of a flourishing improvisational music scene.

“It’s in a second generation,” says Schools. "There are bands out there a generation after us who were influenced by HORDE. Back then we were so glad to meet a band like Phish or Blues Traveler because for a while we thought we were the only ones doing this. It was us against the world. You meet some likeminded fellows and you breathe a sign of relief. There were bands out there who, when they saw the success of HORDE, realized they could do this.

“We described the full band segue to a local stagehand, where actually during Blues Traveler’s set you roll the drum risers and the rest of our stuff on the stage and all the drummers would be playing and both bands would go onstage for an extended jam and gradually they would drop out so in fact there was no stop between sets, and you could see the look on these union stagehand’s faces when we told them what our intent was.”

“We were all on the club scene and we imagined that if we all got together we’d have enough support to sustain a shed tour,” says Bell. “More folks would come out and we’d be able to hang together. Because we were all working clubs we never got a chance to see each other play. And Bruce was on it. He was our inspiration.”

“Bruce was something else. Some nights the Aquarium Rescue Unit would tune differently. You’d be trying to jam with them and you’d realize they were in a completely different tuning from the night before.

“Bruce would call it ‘The Lord’s key,’” laughs Schools. “I’m sure ever time we played with Aquarium Rescue Unit it sounded unusual. Those guys ruined us the first time we saw them. They opened up for us, and there was a guy with an egg beater, Oteil was playing his bass with a balloon, we said ‘that looks like fun’ so we went up there and tried to soak that stuff up. They brainwashed us. We learned a great lesson, which is be yourself. He’s a Zen master. On the first HORDE tour at the show at Lakewood, Béla Fleck and The Flecktones went on before us. Victor Wooten was doing his bass solo and by the time he had done everything he could have harmonically done to the bass he started swinging it around on the strap like a hula hoop. Then he did a free standing back flip then went back into the song. I was standing there with Bruce and Bob Sheehan from Blues Traveler and we looked at Bruce as if to say ‘What are we supposed to do after that?’ And he said, ‘just go out and do what you do.’ It’s the hardest thing to remember sometimes. Of course, what he does is duct tape the bass player to the drums during the show, or stack all the chairs up on stage. It’s a piece of performance art. When he played the Atlanta Pop Festival with The Allman Brothers, Duane said Bruce was his favorite guitar player. We’ve all make lots of room in our hearts for Bruce.”

The bonds of friendship formed with other bands are indicative of Widespread’s embrace of collectivity: They would rather collaborate than compete. “If you go way back to when we were in clubs and we the whole HORDE thing started, we played with a lot of bands, meeting them in clubs, and that friendship just naturally developed,” Schools explains. “The HORDE thing developed out of that, we did tons of shows with Blues Traveler, we did lots and lots of shows with Col. Bruce and then there are the local bands like Bloodkin, Allgood and Dave Matthews, we used to do clubs with them.”

HORDE began as a collective concept, but quickly grew to become something else and Widespread left after only two years. “We did the first two and it got weird,” says Schools. “Blues Traveler had their agenda of having a big hit record. They started bringing in Neil Young and the Allman Brothers to headline and that seemed to run counter to the original idea. Even by the second one it had become a springboard. Management companies and record companies had started to see that the Dave Matthews Band had its big success after doing the second one and all of a sudden it seemed like a formula: put your new band on the HORDE festival and sell a platinum record.”

“They were booking icons,” says Nance, “and the idea was for new and upcoming bands to put their strengths together and go out.”

THAT’S THE BEAUTY OF WHAT WE DO

The band’s ability to stick to its principles applied to its decision to sign with Capricorn Records in January 1991, instead of the more high profile companies looking for an MTV act. Widespread Panic had never let a company dictate a time frame for releases and only puts out albums when the band is completely happy with the material.

“We were too stupid to know that we were fighting a big battle,” Bell offers. “I don’t really mean stupid, we believed in ourselves so much and what was happening and the fun we were having that it was like, ‘Screw you man, look at how much fun we’re having. We don’t have to follow any business plans you come up with.’”

“We never really even bothered to listen to those people,” adds Houser. “We just kind of …went through it all without really knowing what we were supposed to do. Instead we did what we wanted.”

“It seemed obvious to us,” Nance adds. “We had a record company really pursuing us at one point. We never signed that deal but we did go through this tortuously protracted period where we were delivering them demos and they would come back with terms like ‘too electric’ that we thought were silly.”

“We partied with the guy who was trying to sign us to the label,” says Bell. “He came down from New York and he was all happy and had a great experience, but then he’d have to listen to the rap that his bosses gave him, and then he’d call back and regurgitate that rap.”

“We were over in negotiations with these guys,” says Nance. “The contracts were huge. And we just decided that we shouldn’t do it.”

“In the end they wouldn’t even accept our demos,” says Schools. “They kept coming back with these opinions that we should shorten songs and they didn’t like the fact that we had solos in our songs. We weren’t delivering them these neat little packages of trendy hipness.”

“That they knew we had it in us if we bore down inside,” Houser snickers.

“And they tried to split us up a little bit,” Bell recalls with a hint of anger, “saying, ‘Hey, you now I bet you’ve got a long all by yourself.’ I was like, ‘Did you hear what these guys just said?’”

“Plus we have the real-life example of a band who weren’t really friends of ours but they were on the southern circuit,” Schools explains. “I don’t want to use any names, but they got signed by this conglomerate we were talking to at the time, they recorded a record, put in a lot of effort. It was a big budget record and the record company shelved it. It never came out and it killed this band’s career. They were doing really well and all of a sudden they were in between a rock and a hard place. They broke up. The other guys weren’t happy with these songs that we were happy with and we couldn’t understand why they weren’t happy with them, whereas Capricorn sort of opened the doors, said ‘We dig this stuff.’ They understood and certainly any label that puts out a record with a two-sided guitar solo will understand a six-minute song. They had opinions but they were usually positive ones. If we gave them something that happened naturally with us then they were happy. They always let us have that control.”

Capricorn released six Widespread albums over the course of the ‘90s and promoted the group as the spearhead of a new wave of southern rock.

“They were thinking it would be easy for them to just use what they were known best for,” says Schools. “Somewhere along the line where they got confused is that they had a younger generation of people on staff that sort of split their listenership after a few years of signing bands like 311 and Cake, after having rebuilt this southern rock thing with us and Bruce Hampton, Tinsley Ellis, Randall Bramlett and The Dixie Dregs. They created to a certain degree a kind of renaissance of what they stood for and then all of a sudden they confused the issue by signing what was MTV-worthy at the time.”

Largely because Capricorn was so supportive, the group went along with the southern rock label. “It’s like any other label,” says Bell, “like jamband or Grateful Dead cover band, which is actually something we could have been accused of legitimately. In our first two years we played five or six Grateful Dead songs. We did ‘Fire on the Mountain.’ We also did ‘Cream Puff War’ which they didn’t play live. We still do that sometimes.”

The band’s sound evolved during the Capricorn days after JoJo Hermann joined, filling out the arrangements harmonically, adding another solo instrument to the mix and eventually adding another writer to the group.

“I was playing on the same circuit in a band called Beanland, from Oxford, Mississippi,” says Hermann. "We were doing some of the same clubs, Memphis and Mississippi. We opened for them a bunch of in Atlanta and Athens and I got to know them.

“One day I was sitting around and not doing much and I got a phone call. They were like, ‘You wanna go on the road?’ That was back in ‘92. Ten years ago now. Wow. I had jammed with them a little bit. They didn’t have a keyboard player when I first met them in ‘88. Then they got a session guy for a little bit to do that second album, T Lavitz, he wasn’t a band member, and I think they just wanted someone they wouldn’t have to pay nearly as much.”

Hermann’s keyboard touch made an immediate difference on Everyday, but by the time of Ain’t Life Grand he began making signifigant songwriting contributions.

“At first it was just about playing keyboards and fitting in,” Hermann recalls, “helping the band be what it wanted to be, but after about three years I wrote this song called ‘Blackout Blues’ and they liked it. They’ve always been open to anyone bringing in ideas. The whole ethic of the band is if somebody wants to something, bring it in. I definitely have an eye toward the music of North Mississippi, like Junior Kimbrough. There’s a song called ‘Junior’ on Ain’t Life Grand. I played the guys that Junior Kimbrough stuff when it first came out and they loved it. I’m into Professor Longhair stuff which we’ll break out once in a while. We’re all free to do that. That’s the beauty of what we do.”

JUST GIVE US A CALL

The turning point in the band’s career came in 1998 with the release of the live album,Light Fuse, Get Away, a powerful two-disc set that finally displayed Widespread’s strongest suit: live performance. To celebrate the album release, Widespread played a free concert in the center of Athens that drew a crowd of 100,000, stretching as far up the street as the eye could see.

“It was like a dream,” says Bell.

Light Fuse, Get Away also included a guest appearance by saxophonist Branford Marsalis, who band Buckshot LeFonque had toured with Widespread.

“The Buckshot LeFonque project really lent itself to being part of the same evening with us,” says Schools. “Watching that happen was great because we did three shows and the first night they just kind of stuck around and watched us play. The second night Branford said he was gonna come and watch us play so he came and played. By the third night we had the DJ and drummer and keyboard player, the whole band was out there and that’s where the track that was on the live record came from, that third night. The actually played a good portion of the whole first set with us, I think. There was some jamming with the turntable guy that is great. It’s a highly sought after tape. I’d like to listen to it again.”

With the live album on the market, Widespread had a lot of time to think about the next studio project and they all agree that ‘Til the Medicine Takes brought them to a new level in the studio.

“I love that record,” say Hermann. “We had like 20 songs to choose from. Also, that was the one where we brought in the gospel choirs, horn sections, the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, Dottie Peoples came in, the turntable guy Colin from Big Ass Truck came in, Ann Richmond Boston. We really made it into a studio effort rather than just us coming and hammering out what we do live, then putting it out like a live record. It was a lot of fun.”

The collaboration with the Dirty Dozen became another defining moment in Widespread’s musical growth. “Todd had a mix tape that had a bunch of Dirty Dozen songs on it and when we were recording ‘Til the Medicine Takes, we felt it would be a great idea to have the horns on it,” says Schools. “We wanted it to be ‘Christmas Katie,’ I think John had wanted it to be ‘Blue Indian’ but we convinced him and we did the session.”

“We had already played with them at a Halloween show,” adds Bell. “When they were walking offstage after the jam, Roger says ‘Y’all ever wanna do some studio work just give us a call.’ So the next album we had three shuffle tunes and we were looking for a way to make them different and voila. Then we did the summer tour with them. That was a blast. Almost every day we learned a new song with them.”

The interaction between Widespread and the Dozen during that tour was remarkable. The two bands worked so closely together that you could hear them transform into another entity. “When we play with those guys we become another band,” says Nance. “We all play a little bit differently, make room for everybody.”

“They’re just such great musicians,” agree Ortiz. “They know their instruments inside and out, they worked so well with us that it’s almost like they became part of us. We’d go into the practice room and work on new material and when we looked at the finished product we had an album there. As far as I’m concerned those cats can come up and play with us anytime.”

“Previously when people would sit in with us it was a soloist,” adds Schools, “and I remember thinking they can’t just come up and jam with us because they’re a horn section. I was forced to eat my words because they have their own vocabulary. They work as one. Imagine being in a band since you were 14.”

Widespread’s relationship with Capricorn ended in the summer of 1999 but the band put out a great live document of the tour with the Dirty Dozen, Another Joyous Occasion , on their own label, Widespread Records. At the dawn of a new millennium, the band found itself without a label but because it had relied on its audience rather than the record industry for survival, Widespread Panic was in a stronger position than ever.

“Not following the pendulum of trendiness has worked for us,” says Schools. “We’re gonna continue to do what we do no matter what. It’s gotten easier now that we’ve beeen able to consolidate our markets and don’t have to play 200 shows a year. We can play those arenas and make it sound good.”

In October of 2000, Widespread found a new home on Sanctuary Records, which released last year’s excellent studio album, Don’t Tell the Band , which contains several crowd-pleasers. The title track, with its theme of a band playing at disasters ranging from the Civil War to the Titanic and finally the end of the world, took on eerie new meaning after September 11. “Holy shit man, when we were playing that song after September 11,” Bell marvels, “there was a long period of awareness of that for me. Like that night we thought we had lost Gomer [former crew member Bill Jordan]. Every song was Gomer.”

“The line that got me,” says Schools, “was in the David Byrne song ‘City of Dreams,’ which has that line, ‘If we could learn to live together’ and you could hear this collective sort of gasp of awareness every time we played it. It hits you onstage as well because everybody is suddenly thinking about that line instead of Southern USA line which usually gets a big cheer in a different spot of the song.”

Another big crowd favorite on Don’t Tell the Band is Hermann’s rollicking “Big Wooly Mammoth.”

“It’s a painful song to play, actually,” says Nance. “They throw lighters at us when JoJo sings ‘Throw me some fire.’ We get pelted.”

“It doesn’t always work but I just learned to keep your eyes open and you can dodge them a little better,” laughs Bell. “We don’t play it in theaters with balconies.”

“It went through a lot of transformations,” says Hermann. “We heard this R.L. Burnside record and decided to take a groove from one of his songs. As for the lyrics, I don’t know where they came from. I must have had too many beers at the time. I guess I had a dream that I was a mammoth or something. The evolutionary reject – I can definitely sympathize with that. It’s about, no matter what’s going on around you just stick to the things you believe are true, stay true to yourself. It’s also about appreciating the things around you.”

“Mammoth’s” warning against global warming is about as close as you’ll come to finding a political statement in a Widespread Panic song. Bell in particular is wary about using his position to promote a message.

“I think folks inherently wanna be happy and want other people to be happy,” he explains. "You can work together, work side by side, work apart, and let everybody do what they’re gonna do. The only thing is to create an environment in which you’re free to choose. I don’t think we’re really preachy in what we do. If I’m introducing an idea, a thought or a feeling, I look at it as everybody is free to do what they’re gonna do, we shouldn’t get in the way. I think the cool thing is like with music and the interaction with kids, they have a moment to shake off a little of any preconceived stuff and maybe get in a place where they get to readjust and feel what they really feel, think about how they really feel. I’m not saying that people don’t already know that, but once in a while a good shake-‘em-up is a good. I think we just create a vibration onstage musically. They’re our words but we’re just going through stuff like everybody else is and we report on those things. There’s some happy things, there’s some hopeful things, there’s some bluesy things, life isn’t perfect in our world and we sure don’t pretend it to be. We do play it out in a musical sense and share that with each other.

“If we’re part of an environment where folks are inspiring themselves, then it’s cool, it’s like people learning to fish. We’re not handing it to them. It’s in ‘em. Folks know what they want. I think folks really want a happy, healthy, fun, exciting, adventurous life and if we’re helping augment that, that’s cool. But I don’t think we’re causing it.”

“It’s an inadvertent byproduct of us just being who we are,” Schools adds. “We approached how we created our music in the beginning as a live-and-let-live, learn together kind of thing. Anybody who comes to see us can’t help but be affected by the way that we do things, it is there. I do think that our crowd as a whole seems to look out for each other.”

Widespread Panic has come a long, long way from the days when it dined on day-old burgers and lived together in a candlelit cave of an apartment. But success has not budged the group away from its ironclad commitment to the values that continually keep its music evolving. “You keep trying to put yourself in a position where you’re surprised,” Bells concludes, “and you let yourself be surprised by what everybody else is doing, too. The some stuff’s gonna happen and all of a sudden people go, ‘Wow, all this stuff is different, you’ve grown so much since the last album.’ Maybe that’s what growth is.”

Widespread has indeed grown steadily. Each year they sell more tickets – they played to half a million people last year – and each record has consistently outsold the last. Live at Oak Mountain has already gone gold and the new association with Sanctuary has the band poised to become a global phenomenon. But in the end it will always be the music that matters, which why Spreadheads from Atlanta to Istanbul are gearing up for what promises to be a tour with Widespread Panic at the top of their game.