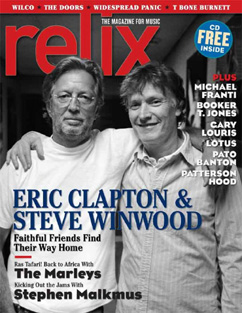

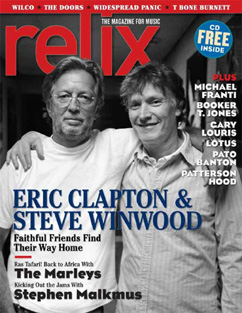

Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood: Faith Renewed (Throwback Thursday)

Eric Clapton’s new studio album, I Still Do will come out tomorrow. On the eve of the release, we look back to our April-May 2008 cover story.

The first time through it all ended in haze and chaos.

On July 12, 1969, nearly 20,000 shaggy, eager concertgoers braved the police presence and the poor acoustics at Madison Square Garden for the U.S. debut of a group that had recently emerged from a shroud of rumor and speculation. Just one month earlier, five times that number had made the pilgrimage to London’s Hyde Park to witness the first public performance of the band that paired Steve Winwood, at age 21 already a celebrated veteran of both The Spencer Davis Group and Traffic, with one of the rock era’s newly-anointed guitar gods, Eric Clapton. Clapton had dubbed the group Blind Faith, something of a cynical nod to the hype machine that had quickly surrounded the formation of the group that also featured Cream drummer Ginger Baker and Family bassist Rick Grech.

Blind Faith’s MSG appearance was marked by tension both within and outside the confines of the band room. Audience anticipation approached frenzy levels for the group that many imagined would somehow build on the power of Cream and take that group’s music to some ineffable, unattainable next level. This expectation was fueled by a sense of unknown since Blind Faith’s self-titled debut wouldn’t be released for another eight weeks. Meanwhile, the band found itself uncertain of its own direction but generally unified in a wariness to revisit its members’ prior endeavors, opting to build something new, which no doubt left some fans unsettled by a one-hour performance that offered little in the way of familiar signposts.

Meanwhile, the show itself took place at that cultural moment when rock was just finding its way into arenas. In an effort to maintain intimacy, the stage was set up in the middle of the floor where it slowly rotated, resulting in periodic obstructed views and wildly uneven sound (The New York Times reported, “The Garden sound system was bad, and the breaks between the songs were punctuated by indignant shouts to that effect” ). In addition, uniformed police officers had been assigned the MSG beat and maintained a steady buzzkill presence in the aisles and alongside the perimeter of the revolving stage.

The collective strain reached its apex deep into Blind Faith’s set when Ginger Baker lost a chunk of a drumstick during a particularly vigorous solo. A young concertgoer climbed onto the stage to retrieve the souvenir and was met with aggressive, physical restraint by some of the officers on duty. A fracas then ensued, with Baker himself entering the fray. In many respects this jarring culmination paralleled the fate of the band itself.

Nearly 40 years later, on a brisk February afternoon, Steve Winwood muses on those events while nursing a cup of freshly-brewed orange tea. On the day after wrapping up his three-show return to the Garden with Clapton, Winwood is dressed casually and comfortably in jeans and a blue sweater. As he settles into his chair in a hotel suite that overlooks New York’s Central Park, he holds eye contact and carries the affable, approachable air of that friend’s father who always strives to make a sincere connection. Or perhaps, he’s the laidback history prof, who elicits a confidence and energy in his students as they address a topic that remains familiar to him yet engaging in all its nuances.

Winwood remains in the present yet he is perfectly willing to trek backwards and reflect upon a career with tangible pride with a lack of self-importance. However, when it comes to Blind Faith’s lone appearance at Madison Square Garden, he laughs and freely acknowledges a failing (which likely would disqualify him from the history gig), “I’m hopeless on memories, partly because I was under the influence, in a fog of wacky ‘backy. So I don’t remember much about that those times. Eric seemed to remember it clear as a bell and he was also under the influence of various other things if we can believe what was written in his book. He said we played in the round and evidently there was a big hoo-hah at the end with police cordoned around the stage. I don’t remember this but apparently Ginger Baker was throwing drum sticks at the policemen and hit one on the head.”

Winwood is a little clearer on the fate of Blind Faith, which wrapped up its American tour a few weeks later and then simply folded its tent, with Clapton lighting out for the territories with the opening act, Delaney & Bonnie.

“The thing about Blind Faith, is its crowning glory I feel was the record. Then after that commerce reared its ugly head a bit and starting pushing and pulling and swaying decisions. There were a lot of things going on in Eric’s life and in mine, too. I’m not sure we quite knew where we wanted to go and somehow the record expresses that. There’s a slight searching quality about it, which I think is very nice. But the searching quality of music doesn’t translate into Madison Square Garden, which needs straight-ahead powerful stuff. They were expecting a Cream-like concert and we didn’t want to give them that. At some point I think Eric even refused to play a guitar solo – he wanted to be a rhythm guitarist.” This was a period of great uncertainty and frustration for Clapton, who wanted to push and shape the music in a new direction yet remained wound within himself, unable to articulate his vision. Over the course of the U.S. Blind Faith tour he increasingly spent time on the tour bus and onstage with Delaney & Bonnie, abdicating much of the responsibility for Blind Faith (Clapton would go on to tour as a sideman with that group before nabbing three of its members to form Derek & The Dominos).

While these events were taking place, Winwood was able to observe and react to them but it took the publication of Clapton’s autobiography last year for him to understand them. “Back in those heady days I was a little unsure of where I was going and what I was doing and now after reading Eric’s wonderful book I realized that Eric was having perhaps a bit of trouble knowing where he was going or what he was doing.”

Blind Faith had emerged from Clapton and Winwood’s loose jam session which took place in early 1969 at the latter musician’s cottage in a remote section of the British countryside. A few days into their efforts, a knock came upon the door and Ginger Baker materialized to volunteer his services. Winwood now recognizes that his enthusiasm for the drummer was not matched by his house guest.

“Eric says in the book that he didn’t want Ginger. Ginger’s a great guy and I know Eric likes Ginger a lot now but there was something going on where I suspect Eric wanted to break away from Ginger’s style of playing and he really didn’t want Ginger in the band. I, on the other hand, saw Ginger as a great drummer and I was eager to try to combine my music with Ginger’s playing, so I kind of fell in with that. I don’t think Eric was very happy with that but those were strange complicated days and none of us spoke about that really, which is odd isn’t it?” Clapton’s memoirs also acknowledge a broader communication gap.

Looking back, I realize that from the start I knew that this was not what I really wanted to do, but I was lazy. Instead of putting more time and effort into making the band into what I thought it ought to be, I opted instead for the laid-back approach which was just to look for something else that already had an identity.

I completely ducked the responsibility of being a group member and settled for the role of just being the guitar play.

Following the dissolution of Blind Faith, the pair rarely spoke at all. The two would occasionally find themselves at the same events and Winwood was on hand to support Clapton’s return to the stage following a period of drug-induced isolation in the early ‘70s. However, by 2007 the pair had not performed together publicly since they shared the stage for a few songs at Ronnie Lane’s 1983 A.R.M.S. (Action for Research into Multiple Sclerosis) benefit concert, which took place at London’s Royal Albert Hall. In 2005 Clapton asked Winwood to contribute synth to a cover of George Harrison’s “Love Comes to Everyone,” just as Winwood had done on the original version, for a tribute that Clapton recorded following Harrison’s death. Yet even that collaboration ultimately took place in separate studios ( “I told Eric, ‘I can just do it here and send you a sound file and then I’ll gladly come in if you think that we haven’t quite got it but this way it’ll save you on studio time and economize the whole making of the record.’ So I sent it and Eric who has a certain grasp of technology found it astounding that I was able to do a take and send it via email. He said, ‘How’d you do that?’ and I said, ‘Eric, it’s not rocket science.’” ).

The writing of Clapton: The Autobiography may well have altered this relationship. It seems quite feasible that portions of the Blind Faith chapter were directed at Winwood, in an effort to share Clapton’s anxiety and angst. Or perhaps rather than seeking to make amends, the guitarist’s reflections simply led him to take stock of an old mate and aspire to move beyond a casual friendship that once carried the potential to be so much more.

This opportunity presented itself last May at England’s Countryside Rocks benefit concert, organized by activist group the Countryside Alliance, which lobbies on behalf of rural communities. Both Clapton and Winwood have occupied country estates since the Blind Faith era, so their interests were aligned. Winwood signed on to perform with his band and soon came to learn that Clapton also had agreed to appear but only if he could guest with Winwood and his group.

“I said, ‘Fantastic, so I’ll play for 35 minutes and Eric can come up and do a couple songs and that will take us to 45 minutes,’ because there were lots of other people on the show. So then Eric called and we started talking about possible songs and we ended up having eight or nine that we were excited about. So I said, ‘Let’s sit together, have a play and we’ll do the best two.’ And he said, ‘fine.’” After rehearsing a few days prior to the event, the two were unable to winnow down their selections and Clapton ended up joining Winwood’s quintet for seven songs, including Blind Faith’s “Had to Cry Today” and “Can’t Find My Way Home.” Still, the highlight may have been their poignant performance of “Presence of The Lord.” The song was a fitting one for the event as Clapton had composed it to express his feelings for his country home, Hurtwood Edge. However, when recording Blind Faith, Clapton’s insecurities prevented him from singing it. Clapton describes the conflict that ensued in his autobiography:

Steve had said, when I wanted him to sing my song “In the Presence of the Lord,” “Well, you wrote it, so you ought to sing it.” I had insisted that he should, and while we were recording it I kept interrupting him and suggesting that he sing it in such and such a way, until he finally said, “Please don’t tell me how to sing it. If you want it sung that way, sing it yourself!” He was quite aggressive about it, and I was a little taken aback and decided to just let him get on with it. Looking back, I know he was right.

At Countryside Rocks both Clapton and Winwood shared verses, suggesting that any lingering ill will had abated now that Clapton had found his voice.

The two performers continued their tentative steps in July at Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festival in Chicago. There the host returned the favor from two months earlier, inviting Winwood to join his group for an extended stretch. A positive experience then led to a conversation about some additional performances, which ultimately were scheduled for Madison Square Garden on February 25, 26 and 28.

“My first question was, ‘Is this going to be a Blind Faith reunion?’ ” Winwood recalls, “He said, ‘No, not without Rick’ [Grech, who had abandoned his career as a professional musician in the late 70s and later died in 1990 of a brain hemorrhage]. Anyway, he wasn’t sure whether Ginger could actually get in the country because he thinks he has visa problems. It was always put together as a one-off or three-off shows, so if Eric had come to me and said, ‘Look I really want to do a Blind Faith reunion, what do you think? I would have said, ‘Yeah, let’s have a go at it.’ But he didn’t and that was fine as well. In fact, he just had a Cream reunion so maybe he wanted something a little bit different and I think that was right.” Clapton respectfully declined to be interviewed for this story having just down a round of press at the end of last year around his autobiography and in showing deference to Winwood and his new album. As for the setlist, Clapton suggested that as a starting point, each of them would select songs for the other. This decision added a vitality to the affair, in direct contrast to the Cream reunion, which by the time of its three U.S. dates, also at MSG, ultimately collapsed under the weight of a dated catalog (as well as the escalating ego clashes among its three band members, another reason why Clapton may not have been keen on enlisting Baker for another go at Blind Faith).

Winwood and Clapton then agreed upon a backing band that varied the instrumentation from their current groups. Whereas Clapton’s steady touring collective features eight additional musicians, including two other guitarists (Derek Trucks and Doyle Bramhall II), this group would be much leaner. Clapton would be the sole guitar player for much of the evening (save for Winwood’s interludes, more on that momentarily). Meanwhile, Winwood’s current group also incorporates sax and percussion, while he handles the basslines on his Hammond. By contrast, for the MSG performances the pair selected bassist Willie Weeks and keyboardist Chris Stainton (Weeks first toured with Clapton in 2006, while Stainton has been a presence since 1979), along with drummer Ian Thomas, who backed Clapton and Winwood at the Crossroads Festival.

As the musicians then gathered in England for their initial rehearsals, Winwood noted a dramatic change in his Clapton’s role since their previous such undertaking a few decades earlier. “Surprise is not the right word but certainly Eric had developed from a virtuoso musician into what I would call, an m.d., musical director. In the early days he just wanted to be someone in the band, never even wanted to think about being a band leader. That was always what I felt was my job, what I did, but now of course he’s great with ideas.”

The rehearsal sessions yielded both new arrangements on familiar material and as well some selections that had never been performed by the pair. Winwood and Clapton shared vocals on numerous songs long associated with one or the other, including “Forever Man,” “Tell the Truth” and a take on J.J. Cale’s “Low Down.” While Winwood pushed and complemented him, Clapton contributed animated guitar to Otis Rush’s “Double Trouble” and lent some wonderful counterpoints to the Traffic instrumental “Glad.” Meanwhile Winwood slung on his guitar and stepped forward for a solo on the version of “Cocaine” that appeared during the final two shows ( “I got a big cheer and I felt it was probably because for effort and bravery to stand next to Eric Clapton and play a guitar solo on ‘Cocaine.’ I’m sure there is an element of that.” ). Another standout were two solo selections, with Clapton offering a nod to Robert Johnson on his acoustic guitar and Winwood settling in behind his Hammond B-3 for “Georgia on My Mind,” (in his autobiography, Clapton writes of hearing a 15-year-old Winwood performing that song in clubs, where, “If you closed your eyes, you would swear it was Ray Charles.” )

Clapton and Winwood also acknowledged another aspect of their shared history by performing two consecutive Jimi Hendrix numbers, “Little Wing” and “Voodoo Chile.” Winwood explains, “It was my suggestion to do ‘Voodoo Chile’ partly because of our connection with Hendrix. Then Eric reminded me that Derek & The Dominos did ‘Little Wing.’ So we thought to put the two of them together. We used to run into Jimi all the time in those days, there were lots of festivals where everyone would play. I did that session [Electric Ladyland] and Eric also got to know him as well. We were contemporaries of his.” The poignant reality that Hendrix’s contemporaries are few and far between was illustrated when Band of Gypsys drummer Buddy Miles passed away on the day of the second show. In a synchronous turn of events, Miles’ “Them Changes” had been a late addition to the setlist, not in recognition of his failing health but rather because Weeks had played a few licks during rehearsal, which caught Clapton’s ear.

Still not all the suggestions found their way into the final performances, which they decided to cap at two and a quarter hours, the maximum length deemed desirable for a single set of music. Winwood remembers with smile, “I chose ‘Pretending’ and then when we started rehearsing, Eric said, ‘I can’t really sing and play the lead so you’ll have to play the lead.’ So I spent weeks learning all Eric’s stuff which was okay. I think it’s written by Jerry Williams and he sang it with Eric and he’s in my range. So I was going to sing all these harmony lines and play Eric’s guitar. It was just getting to be too much.”

Some of Winwood’s compositions similarly did not make the final cut. These included “Spanish Dancer” and “Help Me Angel” from Arc of a Diver and Taking Back the Night, the two records he pieced together entirely by himself during the early ‘80s in his home studio. Winwood also explains that a few of Clapton’s picks from “my kind of pop flirtation era” were not rehearsed (although “Split Decision” a song Winwood wrote with Eagles guitarist Joe Walsh for Back in the High Life did make it to the stage.

Winwood sets down his tea cup and leans slightly forward as he begins a discussion of his solo career. The gesture is somewhat reminiscent of the body language he employs while sitting behind his Hammond B-3. This proves fitting because although he appears on the cover of his album Nine Lives gripping a guitar neck, he defines his current group as an “organ-based band” and he identifies his mission in part to “carry on the legacy of that style of organ playing into the rock-jazz-folk music world.”

“Now I’m doing the bass on the organ. I’ve had much more of a connection with the organ lately, since I learned how to ‘Kick the B’ as they call it. I always kind of did it in the old days, I did it on all those Traffic records but I only figured out how to do it properly from watching Joey DeFrancesco, Dr. Lonnie Liston Smith and Jimmy Smith and they all did it the same way. There’s a bit of smoke and mirrors that goes on. You have to know what you’re doing with the left foot but then a lot of it is done with the left hand as well. There’s this club in London called Jazz Café, which has a balcony above and the first time I saw Joey DeFrancesco, they had the balcony open so I could sit above him and watch all his drawbar moves and his left hand and I thought, ‘Oh, of course.’” Winwood explored this renewed passion for the Hammond on 2003’s About Time. He describes the album as, “A great breakthrough for me; a great success. It wasn’t a huge seller perhaps but it was in a way one of the most successful records for me, in just getting across what I wanted to do, having a vision of what I wanted it to be and fulfilling that.” He then brought this material to the road, with a group that has come to feature Jose Neto (guitar), Paul Booth (organ and sax), Richard Bailey (drums) and Karl Vanden Bossche (percussion).

The tours following the release of About Time set the tone for Nine Lives. Winwood explains that after spending much of the mid to late ‘80s into the ‘90s in the role of an entertainer (where in some cases he eschewed an instrument altogether, performing solely before a microphone) he wanted to return to his roots and his passion as a musician. Part of this process involved establishing his connection with a band rather than an assemblage of players who would join him onstage for a given tour. Nine Lives celebrates this decision.

“These songs were born out of what the band did rather than just writing some songs and getting the guys and saying, ‘Have a listen: This is what we’re going to do.’ We reached a point when we were touring that where we recorded a lot of jams and all our soundchecks. Then we’d go back and use bits. Jamming is just another term for composing, really.” On the resulting nine tracks one can hear echoes of Winwood’s prior bands although this quintet retains its own identity. The release opens with “I’m Not Drowning,” a spare offering with a haunting, eternal quality somewhat reminiscent of “Can’t Find My Way Home.” Songs such as “Hungry Man” certainly evoke Traffic. A steady percussion throughout Nine Lives harkens back to the Latin Crossings project that Winwood initiated with Tito Puente and Arturo Sandoval in 1998. Meanwhile “Dirty City” provides some familiar tones as Winwood’s Hammond colors the environment before yielding way to a Clapton guitar solo.

“Dirty City” did not find its way onto the setlist at MSG. While it might well have been a lost “promotional opportunity,” such sentiments did not seem to emanate from the stage. Instead, these shows were about revisiting and revitalizing friendships, while celebrating a collective past and quite possibly sowing the seeds for the future. As for potential additional performances, Winwood shares optimism, even if plans remain tentative and long-term. “We always said that we would see how this went and there has been some talk of possibly doing something else. But I am committed now and Eric’s committed too so where and when I don’t know [Winwood and his band will cross the country this summer opening for Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, while Clapton and his group have confirmed shows in both the U.S. and Europe] . In the interim, fans can content themselves in the knowledge that all three MSG shows were filmed for a potential DVD release.

No matter what happens though, Steve Winwood and Eric Clapton certainly have shared their moment in the Garden, one in stark contrast to what had taken place nearly 40 years earlier. The New York audience embraced this shared sense of history and community, while affirming a relationship no longer dependent on blind faith.