The Story of the Ghosts, or How to Build a Forest (Part Two: Growing Ghosts)

Ghosts of the Forest onstage at Greek Theatre in Los Angeles (photo credit: Steve Rose)

Here is the second installment of a four-part series that explores how Trey Anastasio’s Ghosts of the Forest project came to fruition. Part one is available here.

***

At first, Ghosts of the Forest was only envisioned to be modestly ambitious. Anastasio would record a nine song album at his Barn studio in Vermont in the spring of 2018, just a few months after Chris’s death. He would be joined by Phish drummer Jon Fishman and Trey Anastasio Band bassist Tony Markellis, with TAB keyboard player Ray Paczkowski adding keyboard parts not long thereafter. There would be a staged component, and the shows would perhaps blend the new material with more familiar numbers from the songbook. However, the project began to evolve.

Trey Anastasio: Pretty early on, “Beneath the Sea of Stars” was the song that pointed me in the direction of doing a whole live show as a narrative journey. That was when there were only nine songs. It was the last song on the record, and I was thinking of lost family members and friends, Chris, my grandparents, my sister. The Barn is in the woods and full of my grandparents furniture from my childhood, so I think of them a lot.

That song is set up like a long night in the woods, you hear the hooting of the owls, and we go into the woods together with the spirits. Then it gets darkest before the dawn, in that trippy section, and then in the middle there’s a sunrise moment: “morning birds arc in magnetic parade and the dawn is slowly breaking.”

The morning brings a little clarity and hope and spirituality with the “blue all around” part, but at the end, reality hits again and we kind of smash back through the glass right back into the confusion from the beginning of the album. This feels accurate to me when it comes to grief, at least in my experience. A brief glimpse of the big picture, followed immediately by, “Who cares about your stupid concept? I’m just sad. I can’t get over this shit, it’s breaking my heart, and I’m really depressed. Stop telling me they’re in a better place.” So that was a conscious choice to make the album loop back around in a cycle.

I think that song was sort of the trigger point for creating a whole show.

I wanted this to be different than Phish. It should be one set, not two. Pretty early on, it was conceived as a journey, an emotional journey.

Abigail Holmes: They were really wonderful conversations, exploring this wonderful new music, the great musicians who would be playing it, and the best ways to frame that experience on stage. We met on and off over time, which was cool. That let us talk about ideas for the show, and then gave some time to think about things and work on them. And come back and look at them and talk about the next step. Some things really stayed constant throughout, and others we’d come back to and maybe say, “yeah, that’s cool, but not right for this show.” There was enough time to let things develop and then let things go.

Although Anastasio had ventured into musical theater with Hands on a Hardbody (2012), the truer lineage of Ghosts of the Forest’s staging might be found in the challenge of introducing new music to audience members with expectations of hearing their favorite songs.

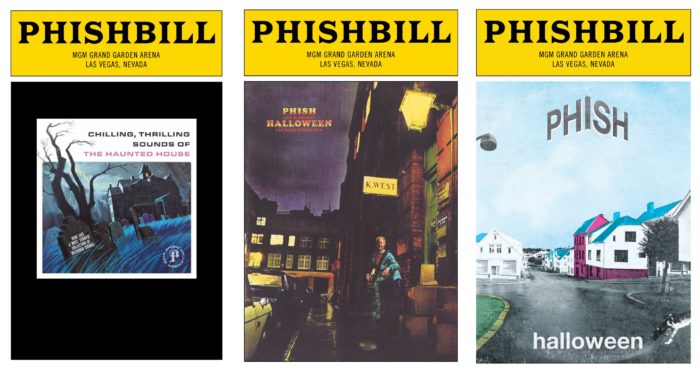

Phish made a low-key art-form of rolling out their new material in creative ways. In 1992, they accompanied their latest batch of songs with a musical secret language, in part to measure how quickly fans spread the tapes. In 1995, there was a whole album’s worth delivered at a Voters For Choice benefit a month in advance of their summer tour with enough time for the recordings to spread before the band hit the road. In 1997, a set of all-new songs (played twice) at the backyard Bradstock gave way to a tour where the band shelved many classics. Since 2011, Phish’s Halloween performances have become a way to launch new material into their repertoire, vacillating with Phish’s typical slipperiness between silly and serious, including 2013’s Wingsuit (which would become the 2014 album Fuego), 2014’s Thrilling, Chilling Sounds of the Haunted House, and 2018’s í rokk, performed in the guise of Kasvot Växt.

Trey Anastasio: I learned from Wingsuit. We put people in the difficult situation of trying to grapple with something they couldn’t viscerally latch onto, and I don’t think it went all that well. As soon as it was over, I was like “whoops, we should have started with ‘Fuego,’” which is what the album ended up starting with. “Wingsuit” is a song we were really excited about, and I still am, I just don’t think it should have started the whole thing off.

Then, the next time we did it, it was Chilling, Thrilling Sounds, and I thought we should start with eleven absolutely visceral dance grooves before the band even got together. The idea being that we’re gonna do this again, but that there was a skill set that was carried forward, so we didn’t make that same mistake again. Instead, we’re going to come out with a bang. We’re going to give people something that they can have fun with, and allow them to come on the journey with us. And then the roof is going to blow off and it’s going to be fucking fun.

Then the next time was Kasvot Växt, where we’re going to do it with more elaborate songwriting, where we really try to say something, and it’s gonna be a party, and the first song is gonna go bang, the stage is going to be white and you can’t take your eyes off it, and it’s a really heavy dance groove. Everybody’s invited to the party. By the end of the first song, I wanted to honor the audience by inviting them on the journey with us and not giving them something that’s difficult to wrap their brains around — because that’s our responsibility.

This time [with Ghosts of the Forest] what was really scary was going a giant step even way further into the personal, honest, and the emotional. It was a risk to walk on stage to a sold out house and know that all I have to do is turn around say “’Sand,’ one, two, three…” and the whole fuckin’ place goes nuts — and not do it. And [then] start singing these songs like, “I’m sad that you died,” and “I feel uncomfortable in my own skin” and “I’m about to run” and all this shit, and not have any idea how people are gonna react.

Abigail Holmes: I’ve been at many Phish shows. I worked with Chris Kuroda on the production design of the recent layout with the moving trusses; and on the show prior with the video surfaces. One thing about the Phish audience is their loyalty, and their level of engagement. It is amazing to be able to make completely new music with a new band and have the audience ready to come and experience it. That is incredible, because it allows risk taking and experimentation. And I think that the audience knows it’s reciprocated. Trey thinks deeply about how the audience is going to respond. We talked a lot about the audience — their expectations, what was going to be different about this show, having moments they would relate to, and also taking them to some new places, and how to find the best balance of those things.

Trey Anastasio: It’s kind of built to be finite. I’m going to try this experiment, I’m going in full, I’m diving in completely. I’m going to let the chips fall where they may, despite doubts. I knew everybody was gonna fuckin’ rock out to Kasvot Växt, because it was built that way. Whereas that wasn’t true on this one. This was part of the conversations with Abbey, about how the production is going to unroll one song at a time. There are no flashing lights. Every piece of production is going to be built on 100% emotion. I’m going to start off with this really slow, sad piano thing. We’re not going to rush it. It felt really revelatory.

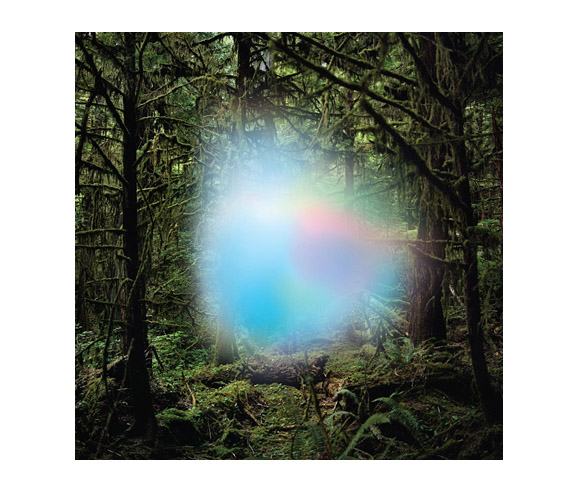

Abigail Holmes: There is a strong sense of place in many of the songs, being out in nature where Chris lived, the idea of Ghosts of the Forest. I had the feeling from listening to the songs that this was partly a real place, but also a mystical place. In my thinking, ideally the visual design would help the audience enter into a sort of journey with the musicians, enter into a world where this music would be played and shared, and step out of the everyday for the time of the show.

Trey Anastasio: That was definitely the stated goal — that there was a sequence of events. It was laid out almost with some of the rules of theater, the main rule being that I know what the whole narrative is, and that Abbey followed the same direction. Even though all the visuals were abstract, she listened to all the lyrics and the music and knew why she making every choice that she made; they were all conscious choices to further the emotion or meaning of the song. Anytime it started to get too literal, she would take it out. She didn’t want a literal definition. There was intent, that was the keyword. There was intent behind every visual based on the meaning of the song to her, and there was intent in every sequence to further the story. That’s where it was different than a Phish show. A Phish show is visceral in the purest sense of the word, the real definition, which means in the muscles of the heart.

Abigail Holmes: We would definitely have an idea for the meanings that the visual design choices were representing — but they were absolutely intended to be abstract enough that the audience could interpret and relate to them individually, not to be so literal that they defined things too completely. It was important to leave space for people to experience it in their own ways. For visuals, I mostly think this was done in a subtle way–a shift in color, or brightness, a change in the video–always meant to enhance what the music was saying.

Trey Anastasio: It’s not a theater piece, but there are skills I picked up along the way to make things carry more emotional weight. You learn little tricks along the way, like the 11 o’clock number, which is a term from the golden age of Broadway, a theatrical tool, the big break-on-through number. In Gypsy, it would be “Rose’s Turn,” where Gypsy Rose leaves, and her Mom has a full-on breakdown and realizes her plight. The character often changes. They call it the 11 o’clock number, because shows in the golden age of Broadway used to end at 11:30. “A Life Beyond the Dream” felt like that song.

There are all these tricks that people have learned from hundreds of years of doing live theater, live performances. Every time I do one of these things, I figure out something new. Doing Hands on a Hardbody taught me so much that I use habitually now — for instance, how to run a rehearsal, how to get more out of a finite rehearsal.

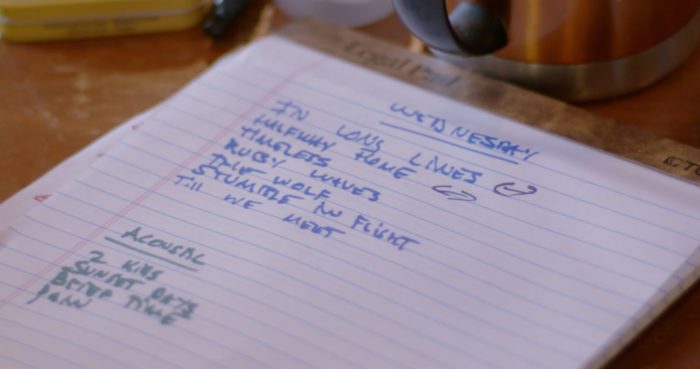

So, with Ghosts of the Forest, I really needed to do this thing that we did with Kasvot Växt, and have some nice moments in the night where people can grab onto a visceral drumbeat for relief. Otherwise it’s too much. With Kasvot Växt, I used these mouth drumbeats that I put on my phone, and I brought them all in and Fish laid them all into grooves, which is where the songs started. So I wrote 26 more Kasvot-style drumbeats, and asked Fish–since he was going to be in New York–if he would mind going into the studio with me on January 1st and recording them all.

Jon Fishman: Phish played New Year’s Eve in New York City and on New Year’s Day–the morning after we just did this four-night run at Madison Square Garden, so I’m in great drumming shape–I went into the studio with Trey. We went to a studio a few blocks from the hotel, and he’s got 25 or 26 mouth drumbeats on his phone. There’s a drum kit set up, and Bryce Goggin had it mic’d up, and I played them. Some of the beats were a little weird, because drum machines and people singing into a phone don’t care where things are on an actual drum set. But all of it was pretty simple because you can only do so much with your mouth at once. What’s great about it–and I feel like I should do this–is that you see things that you wouldn’t play necessarily right out of the gate, so that makes your limbs move in combinations that you wouldn’t have done otherwise necessarily.

There were 15 or so that made it to potentially being songs, from which 10 or something eventually made it to the stage. He sent me the tape of these developed songs, now with some lyrics, guitar, and drums that he and Bryce had spliced together. Some of it, they would take one drumbeat and marry it to another one, and build the song with a bridge and verses and stuff.

Ray Paczkowski: It was uncanny. Trey was telling me that he would go, like [sings mouth beat] and Fish went through it and what he ended up with was the verbatim of what Trey was singing. Trey played it for me. It wasn’t, “I’m gonna take this idea and make a rhythm out of it,” it was, “this is the rhythm and I’m going to make the drums sound like [sings mouth beat].”

“Wider” song progression samples

Trey Anastasio: I knew how it was going to end and knew how it was going to start. I knew from day one that was going to end with that “blue all around” [from “Beneath the Sea of Stars”] wrapping back around. I knew the islands where it was going to go in the middle, that “Beneath the Sea of the Stars (Parts 1 & 2)” would be three-quarters of the way through. So then it was, “How are we going to get into ‘Beneath the Sea of Stars’?” And that was “Green Truth.” That was one of the drumbeats.

***

Next time: Staging Ghosts