The Space Between The Notes: Oteil Burbridge on ‘Comes A Time,’ Dead & Company and Col. Bruce’s Clairvoyance

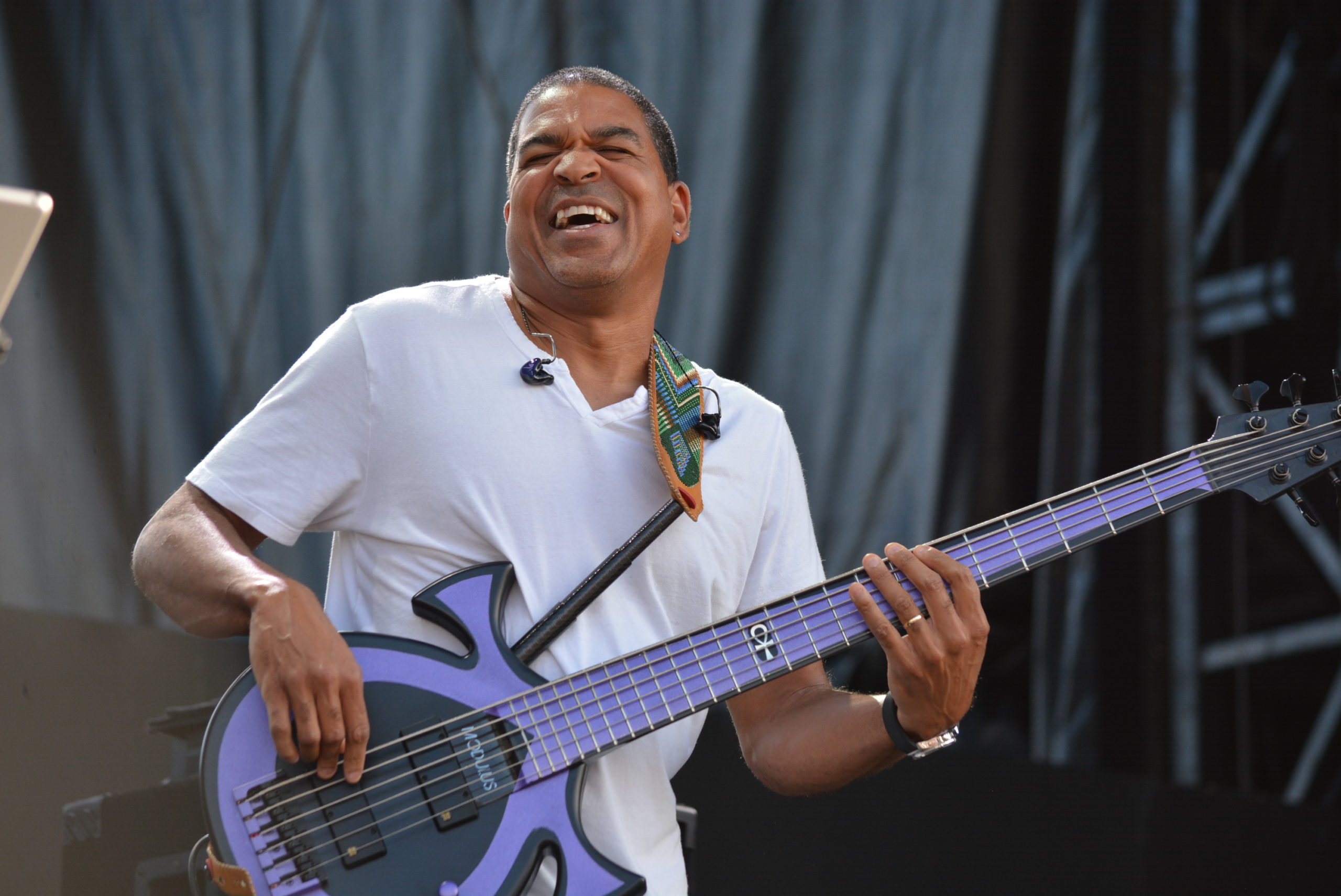

Photo credit: Dean Budnick

“Thank God this came along,” Oteil Burbridge says while discussing his Osiris podcast, Comes a Time. The bassist, who launched the series during the pandemic, along with his co-host, stand-up comedian Mike Finoia, has been able to explore a mix of pertinent social justice issues, as well as some more arcane topics that have long been of personal interest to him. The roster of guests has reflected Burbridge’s tenure in Dead & Company, The Allman Brothers Band and Aquarium Rescue Unit. However, he and Finoia have also extended invitations to Andrew DeAngelo (The Last Prisoner Project), Briahna Joy Gray (National Press Secretary for the Bernie Sanders 2020 presidential campaign) and Dr. Stanley Krippner (Varieties of Anomalous Experience: Examining the Scientific Evidence), who devised the Experiment in Dream Telepathy at the Grateful Dead’s 1971 Capitol Theatre run.

The official Comes a Time description notes, “In these strange days, when you think it can’t get any weirder, it does.” Burbridge adds: “One of the themes of our podcast is that we can’t just go back to normal. That’s a really bad idea. Tell that to the people who are still in jail for weed and mushrooms while we’re out here having the Roaring Twenties. Normal was not good.”

Comes a Time often finds you moving beyond music to explore civil rights, mystical experiences and psychedelics. These are all topics that interest you, yet you hadn’t previously touched on them very much in a public setting. What prompted the podcast and this approach?

For many years, it was just a given that you wouldn’t talk about politics and religion on social media, on Instagram. That’s kind of why I got off Facebook because Instagram seems to be less political. It’s just to advertise your gigs and share some personal stuff. I’ve also shied away from the personal side more as my Instagram has grown.

But then the George Floyd thing happened and, all of a sudden, that was on the table. We can talk about it now. For so long, that was something that you were not supposed to talk about. So we can address questions about fundamental unfairness in so many areas, including education, minimum wage and housing. We can also talk about the fact that weed is legal all over the place but all these Black people are still sitting in prison.

All of this was on my mind, and the way the podcast came about is that I went on Mike’s Osiris podcast, Amigos and we just hit it off. We started talking about some spiritual stuff, some mental health stuff, some really heavy subjects. And we thought, “Man, we should do a podcast about all of this one day.” Then, when the pandemic happened, it was like, “Well, we got nothing but time, so let’s go for it.” At first, we had a lot of musicians and comedians on because that’s who we know. But, then, it always seemed to veer back to what we call the “common sense stuff,” whether it’s spiritual stuff, political conversations, family, mental health. It’s not necessarily right or left; it’s label free.

I love the comedians and the musicians but I also like to get outside of that. And even with the comedians and musicians, I still like to talk about our mental health, our spiritual health, the mental health and spiritual health of the country, the social justice stuff—everything that really matters. Let’s talk about life. Let’s talk about when you were down and what was your moment of grace and what you see now, looking back on it.

That’s what turns me on, and the more we got into the mental health and the spiritual side of things—like psychedelics as a form of mental health therapy—those seemed to be the most popular episodes. My reaction was, “Great. That’s what we wanted to do in the first place, so let’s just laser in on that.”

We had Stanley Krippner talk about the anomalous experiences that people have had and the experiments he’s done with telepathy. That was really a trip, man. We’ve had some good guests, like Paul Stamets, talk about mushrooms, psilocybin and all that stuff. That’s been really fascinating.

The podcast is a way for me to address all these topics in long form—in a way that I couldn’t really talk about in a social media thread. And if you don’t like my opinion on something, then you’re free to turn off the podcast or change the channel. No one’s handcuffed to our YouTube channel. [Laughs.]

Did you connect with Krippner through your participation in the Billy Strings Deju Vu Experiment, and can you describe your experience as a receiver? [Ed. Note: Over six nights of Strings’ livestream, audience members were encouraged to mentally project a specific image to an individual identified during setbreak.]

Yes, Stanley Krippner appeared the night after I was on there, which is what prompted us to reach out. He’s almost 90 and I had just assumed that he had passed. But not only had he not passed, he was extremely lucid. I mean, his memory is better than mine.

The way the Experiment worked was that Billy sent me this big package in the mail, which included a pad of paper and a pencil. The top of each page said, “You are participating in an ESP experiment.” They were recreating the experiment that Krippner did in the ‘70s with the Grateful Dead.

Billy knew that I would be into doing it. However, my particular kind of telepathy—or whatever I have—is usually through dreams. So I was apprehensive but I figured, “What the hell?”

At 10 p.m., I was supposed to stop whatever I was doing, stay off social media, clear my mind and write. So I drew a spoon and a tuning fork. Then, I added some hieroglyphics of an owl, a triangle and a half circle. Then, I drew a boat, the word mirror and the mirror image of the word mirror.

But, when they came on after their second set to show me the image, it was two eyes. When I showed Billy the drawing, he went, “Well, owls have big eyes.” And I was like, “Yeah, but that doesn’t really seem like a direct hit.” Again, I was thinking that’s because whatever I have works more through my dreams.

But, the next day, my manager goes, “Dude, you’re not going to believe this.” Then, he shared a screenshot of the poster for the after-party of the Billy Strings run by the Kitchen Dwellers. The poster had an owl, a plate with silverware and a boat. I hit it three times but, for whatever reason, I didn’t hit Billy. I hit the Kitchen Dwellers.

Then, I saw Stanley Krippner on there the next night and I said, “We’ve got to get him on the podcast.” It became one of my three favorite episodes that we’ve ever done because he knew all these cats that I idolize, like Ingo Swann.

What Krippner was saying—and I want to get this guy Rupert Sheldrake on the podcast who says the same thing—is that a lot of scientists want to be debunkers. They’re refusing to accept the fact that these peer-reviewed experiments have taken place because this doesn’t fit into their belief systems. I’ve known a lot of psychic people—my mother, Kofi, Col. Bruce and plenty more. As Ingo Swann says, lots of us are psychic, but Western society does not train us in it.

Over the years, I saw Col. Bruce Hampton do so many things, large and small, that seemed to defy any other explanation. What’s the first memory of Col. Bruce’s clairvoyance that comes to mind for you?

Oh God, there were so many things. That’s the thing with Bruce. It was not one thing, it was the multitude of them—the regularity that he would freak people out. You know, they say DMT is endogenous. I forget which gland in our brain it’s in, but it’s supposedly released when we die or when something traumatic happens. I think, with Bruce, that gland was excreting it on a regular basis. It wasn’t waiting for him to die. So he had this heightened awareness all the time and, sometimes, it was stronger than others. But he regularly operated on a higher level of awareness. I saw him do so much psychic shit and freak people out completely—to the point where they started screaming.

If he would sleep in close proximity to you at a certain time of the morning—when you’re not in deep sleep—he could see what was going on in your life. I’d roomed with him, so I always knew that I wasn’t going to keep any secrets from him and I made peace with that.

But I saw him absolutely freak out this club owner when we went to breakfast one morning. He just started saying these really specific details about something that only three people on earth knew about. The dude lost it. He absolutely lost it. Bruce was like, “I’m sorry. If I’m sleeping close to you, then I get all this stuff.”

That was just one of a hundred things. It’s just the first one that occurred to me.

There were at least a dozen times when I saw him meet someone for the first time and identify their birthday. A couple of times, when he was wrong, he was only off by a few days, which was still impressive to me.

He used to do this thing where he would get a dollar, and he’d write five numbers between one and a hundred on it. He’d go, “Hey, give me a number between one and a hundred.” So then you’d go “15” and he’d go, “Give me another one,” And you’d think, “Oh, he already missed it.” So you’d go, “25.” Then he’d go, “OK, give me another one.” And you’re assuming he’s just missing them. Then, after you gave him the fifth one, he’d hand you the dollar bill and it would have all five numbers that you just said on it. I mean, what do you do with that?

I wonder about the impact all that had on his career because it seemed like he had a tendency to self-immolate whenever he was on the cusp of success.

He sabotaged it every time.

Was he was conscious of that?

Absolutely. I think success really takes a toll. There’s a lot that comes with being famous and most of it ain’t good. That’s a hell of a wave to surf. There aren’t many people who haven’t been scarred by it and there aren’t many who end up with their minds intact.

I often think of Dolly Parton. She seems to be very well-adjusted. She has the right makeup for fame. Other people who have worked with her have said the same thing. But that’s a rare thing, man. Most people are broken by it, deeply scarred by it or lucky to survive it. I think well-adjusted famous people are few and far between.

One such person who was on your podcast last year is Bill Walton. Even given some of the physical challenges that he’s faced, Bill is overflowing with positive energy.

Absolutely! But we’ve got Bill Walton and Dolly Parton—can we go for five? He’s one of those people and, as far as sports guys, I feel like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is another— someone who’s a shining light and has got it together, spiritually. But that’s a rare thing. It’s a hard thing.

When it came to fame, Bruce was like, “Nah, never mind with that shit. No thank you.” He thought the fame part of it was the worst. He wasn’t ambition-driven in that way. He preferred to be the one that no one would take seriously—the jester. Still, he had so much charisma that it would still happen and then he would have to sabotage it. It was hilarious.

Although on the stage, in the moment, he was ambitious in terms of what he hoped to achieve.

Yes, but he would tell you, “My ambition is to become nothing.” He’d be laughing when he said it, but he was being literal. He was being straight with you. A lot of times, when Bruce was joking, he was actually being the most straight.

He did have ambition but it was Book of the Tao stuff—we come from nothing and nothing is the wellspring of all inspiration. We have to surrender to, and actually try to merge with, that nothingness. And then out of all that comes the creation, just like creation came out of nothing.

When you hear people talk about the space between the notes, that’s the nothing he’s talking about. Out of that silence comes the sound. You can’t fill up all the space; you have to leave some nothingness. In fact, you can leave a whole lot of nothing because it creates a lot. The more nothing you leave, the more anticipation it builds. He was great at that.

He showed me that, and he didn’t even need an instrument to do it. Did you ever see him do the thing where he would hold a shoe up onstage? It was because he said that music had to have the threat of something happening. So you have to be sitting on pins and needles a little bit, expecting something cool to happen. I remember asking him once: “Well, how do you create the threat?” And he took his shoe off and just stood there holding his shoe. People were expecting something and you could see the energy change as they became more uncomfortable—“What’s he doing?” Then, after like four minutes, he would just drop the shoe. And he would get this huge reaction from us on the bandstand, too. I was like, “Wow, he did it without an instrument.” His approach was, “Do that with your playing.” He was really a fascinating person.

It seems like all of that left you well-equipped for Dead & Company, even though you weren’t previously steeped in the music.

That was my blind spot, coming from a tradition that was centered exclusively around musicianship and chops and all that. I had missed the folk-music part of it all. But, folk musicians can still create all that threat and all these human things. Thanks to Bruce, I started to understand more of it.

To me, the music of the Grateful Dead and the Allman Brothers was electric-folk music. They both mixed all these different styles that are here in America into a big gumbo.

I honestly believe that, if I had not met the Colonel, I would not have been in the right mindset to play with either band because I just would have been missing that crucial piece—the human piece, not the musician piece.

Somewhere in that continuum is the Surrender to the Air project. The album was released 25 years ago. What do you remember about those studio sessions or the two live shows?

That was 25 years ago? You just knocked me out of my chair—sorry if I need a minute to catch my breath.

It was so cool, and I remember it so well. We were in Hendrix’s studio, Electric Lady, right in the big room. We had Marshall Allen, Michael Ray and the vibraphone player from Sun Ra [Damon Choice], along with Medeski, Marc Ribot, Bob Gullotti, Trey, Fishman, me and my brother [Kofi].

I couldn’t believe that I was in that room with those people and that we were going to do what I used to do with the Colonel all the time—whether it was just me and him alone at his house, or as a trio, quartet or quintet on a stage. There were no songs—we just went in and made music. I was like, “Man, this is going to be cool.” And talk about a sense of anticipation, a sense of threat building up in a room. I was like, “Oh, it’s on.” And it was just great, man. Apparently, there’s like nine hours of it. One day, I would like to microdose and listen to two hours at a time and, eventually, revisit it all because there’s got to be lot of really cool moments.

Marshall Allen is an otherworldly presence, whose intent seems similar to Bruce. He just celebrated his 97th birthday. When I was last with him at Brooklyn Bowl, he was about to start a six-week tour of Europe, and I’m sure they’re not flying on private planes and stuff. I was just like, “What is this guy made of?” Bruce used to call himself an extraterrestrial and that guy’s another one. [Laughs.] He’s not built like regular humans. He has to be made of other stuff to be doing that. That’s just spirit power. He’s going on literal spirit power.

He’s still living with the band in that same rowhouse they all shared with Sun Ra, even though some of it collapsed in the past year.

Those guys are like Jesus’ disciples. It ain’t ever going to be different, and they’re still going on that power. It’s absolutely stunning.

I’m so glad I got to hang out with those guys. The Colonel took Sun Ra around to all these radio station interviews in Atlanta back in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, and I came along. I saw them live three or four times and, man, that was just unbelievable—Marshall and [John] Gilmore. I also saw June [Tyson] at the Cotton Club before she passed away. She was the voice of an angel crossing many dimensions. It was just unbelievable to be right next to those guys—they were killing it.

The time that I saw him at the Cotton Club, Sun Ra drove out all the people that didn’t get it—the people who’d heard the radio interview and thought it would be a nice date night. He came out swinging this big thing on a chain that was like two or three feet long. He was twirling this thing around and then he went up to the mic and said, “Y’all sure look good tonight.” Then he paused and went, “How long have you been dead?” and pointed to Marshall Allen, who abruptly stuck his horn up over the microphone, so that the microphone was in the bell of the horn. Then he just opened the gates of hell. You could see four tables get up and leave immediately. Then Bruce, forgive my cussing, leans into my ear and goes, “These suit-and-tie MFers are getting out of here like it’s a fire drill.” [Laughs.]

Sun Ra totally did it on purpose. It was like, “We’re going to clear the room before we have church here and then we’re going to do it for real.” It blew my mind. I couldn’t believe it. I’d never seen that kind of musical force.

I’m pretty sure I saw Aquarium Rescue Unit do that on at least one occasion.

Absolutely. Bruce would tell us to do it. He was like, “We’ve got to clear the room tonight.” And a lot of it was based on that. He was like, “Let’s clear the room” and I was like, “You’re on, dude.” [Laughs.] Oh, man, it was great. We did some gigs with Davey Williams, a guitarist from Birmingham, Ala. Davey also played in a band called Curlew that was in the New York avant-garde scene. And if you wanted to clear a room, that guy could do it quick. He was a genius at it. That cat was really something. He had a beautiful sense of abandon.

Back to the topic of folk traditions, the Roots Rock Revival camp returned in August . Can you talk about its origins and development?

If you like the music of the Allman Brothers and the Grateful Dead, then it’s something that you don’t want to miss. It was started by Butch Trucks, one of the two original drummers of The Allman Brothers Band, who wanted to personally pass down the legacy of the group and develop these relationships. That’s what it’s all about— it’s about the people, the campers and the staff at Roots Rock. It’s the musicians and teachers who give their time to it. And it has really grown into this beautiful family that’s also become interwoven into our musical family at large. We have kids who have been coming there for like seven or eight years, and we’ve watched their development.

I love to teach, and nothing is more exciting than seeing musicians when they’re in that growth spurt. They’re really excited and they’re super inspired— playing all the time, practicing all the time. You can just see their playing going vertical. It ebbs and flows, and you’re catching them at that sweet spot.

I’ve watched some beautiful relationships develop over the years at camp. They’ve remained solid throughout the year, and everybody can’t wait to get back.

It’s built around jamming and improv but we’re starting to bring in a little bit more of a blackboard curriculum. We’re not totally teaching music theory yet, but we might get into it a little bit because you need that for harmony. You need to be able to hear intervals for jamming and improv.

We have people of all different ages. We have kids and their parents and grandparents, and everybody brings their instrument. It’s a lot of guitars, but we’ve also got drums, bass, keys, horns. We even have a dude who’s brought an accordion to jam with us.

It’s in Big Indian, N.Y., an absolutely beautiful setting. It’s just stunning—that classic Catskills weather in early-August when it’s not too hot. It’s a great time of year, a beautiful setting, a mix of really beautiful people and great music.