Swing Time: Alan Braufman

The saxophonist’s largely forgotten aural portrait of New York’s early-‘70s jazz scene is brought back into the spotlight thanks to the help of a modern indie tastemaker.

When jazz saxophonist Alan Braufman moved from Boston to Manhattan with a group of Berklee College of Music pals in 1973, New York City was enjoying yet another case of the best-of-times/worst-of-times blues. Rent was low, but crime was high, and then—as now—few jazz musicians were making what you would call a middle-class living.

The pianist Cooper-Moore, then known as Gene Ashton, had secured a vacated industrial building at 501 Canal Street in the neighborhood that would later be known as Tribeca. It was far too hot in the summer and way too cold in the winter. “If you had a bottle of water and didn’t want it frozen in the morning, you had to put it in the refrigerator,” Braufman says. One or two musicians occupied each of the building’s four floors, while its storefront became a weekend performance space. The whole monthly nut was $550.

Valley of Search, the album that Braufman and his band recorded in their storefront during a single take one afternoon in 1974 for corporate lawyer Bob Cummins’ fledgling India Navigation label, provides a fresh aural portrait of New York’s early-‘70s jazz scene. And almost 35 years later, Valley of Search has been remastered and subsequently reissued by Braufman’s nephew, Nabil Ayers, the label manager for indie tastemakers 4AD. It remains a disciplined maelstrom of free- blowing expressionism, deftly handled thematic transitions and convincing spiritual introspection.

“I really don’t like listening to things I’ve recorded, so I hadn’t listened to it since it came out 43 years ago,” the 67-year-old Braufman says from his home in Salt Lake City. “But I was actually happy. The remaster sounds better than the original.”

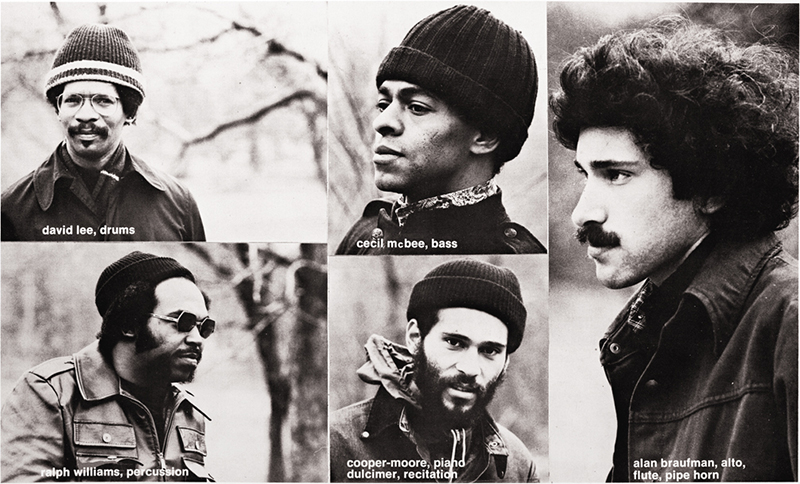

He’s especially pleased with how Cooper-Moore’s piano reemerged from the mix, but the whole band sounds inspired, alone and together. Guest bassist Cecil McBee brings an authoritative swagger to the ensemble free-for-all “Thankfulness” and spins a captivating solo narrative with “Miracles.” (The 44-minute set has been divided into nine sections.) Braufman’s Bahá’i interests are reflected in Cooper-Moore’s recitation during “Chant,” although, as Braufman notes with a laugh, “I wasn’t proselytizing.” Drummer David Lee and percussionist Ralph Williams supply colorfully raucous rhythmic backgrounds for Braufman’s full-throated alto saxophone.

Playing what was known by some as “the New Music,” and by others as “loft jazz,” Braufman and company were swimming in a free-jazz current whose headwaters extend back to when musicians like pianist Cecil Taylor and saxophonist Albert Ayler picked up on Ornette Coleman’s 1959 breakthrough recordings, The Shape of Jazz to Come and Tomorrow Is the Question! While some musicians found such pigeonholing nomenclature offensive—“We didn’t come to New York to play in lofts; we came to make a living,” said pianist Muhal Richard Abrams in a 1977 New York Times article—Braufman simply found it confusing.

“They called it ‘the new thing,’ ‘the New Music’ or ‘avant-garde jazz,’” he says. “I have no objections, but they still called it that six years later, even when it wasn’t new anymore. And ‘loft jazz’ could be anything. You sometimes heard New Music when you went to a loft in those days. But you might hear a lot of hard bop and bebop there, too.”

Braufman, who was raised on Long Island, says the most memorable music he heard while in New York was when he’d skip high school during the late-‘60s, visit his sister in Manhattan and catch Sun Ra Arkestra during their regular Monday-night slot at Slugs’ Saloon, where they performed from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m. without taking a break. He also heard Pharoah Sanders, McCoy Tyner, Hank Mobley, Lee Morgan and Jackie McLean at the same storied East Village hot spot.

During the late-‘70s and ‘80s, Braufman toured with the jazz star Carla Bley, the classical composer Philip Glass and the English rock act Psychedelic Furs. While pitching his second album, Lost in Asia, he found record companies more receptive to “Alan Michael” (his middle name), so he changed his stage moniker for expediency’s sake.

Braufman relocated to Salt Lake City with his wife and children during the mid-‘90s, when New York was merely unaffordable and not yet insane. It was a bit of a culture shock, he says, especially when he realized that “some of the jazz musicians I was playing with were Republicans—crazy.” By that time, his free-jazz years were just part of his musical DNA.

“There’s no free-jazz thing here,” he says, as if we’re still getting accustomed to that notion. “I push it as far as I can and people can relate to.” He released As Daylight Fades (what he describes as “a mix of jazz and some of the psychedelic pop of the ‘80s, like Psychedelic Furs and Tears for Fears”) in 1995, and continues to teach and perform regularly in Utah.

“It’s not a compromise for me,” he says. “I enjoy what I’m doing. I’m playing with the same intensity and spirit I brought to free jazz, just in a different medium.”

This article originally appears in the October/November 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.