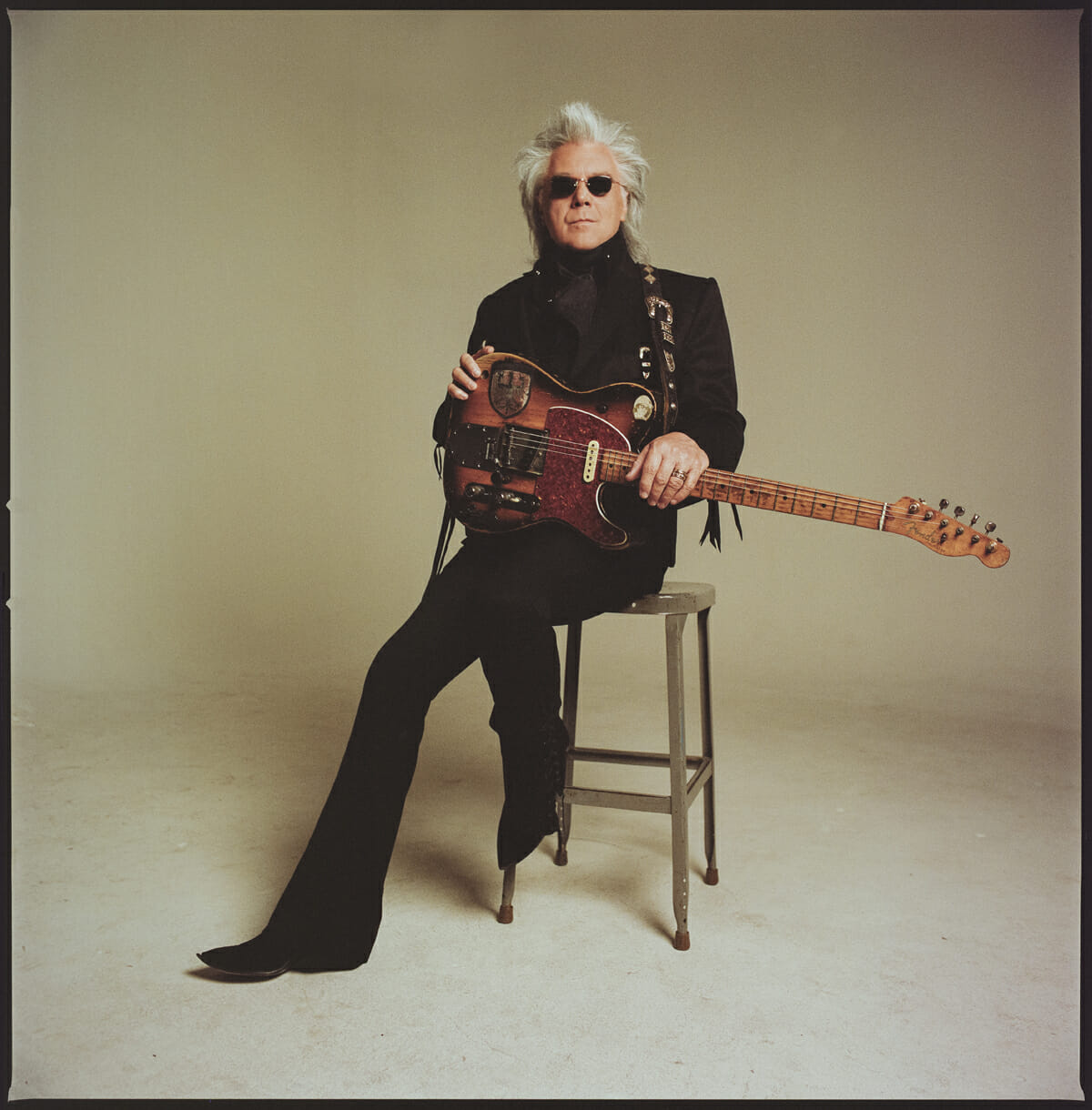

Marty Stuart: Altitude and Elevation

photo: Alysse Gafkjen

***

“With Altitude, all of the things that I’ve been involved in creatively, and in life, just followed me to the microphone yet again,” reflects Marty Stuart, while describing his latest record with The Fabulous Superlatives.

In many respects, the album builds on the ideas and ambience the band cultivated on 2017’s heralded Way Out West. That record presented a palette of sounds evoking California’s role in the development of country music.

The entry point for Altitude was the group’s experience on the road touring with The Byrds co-founders Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman for the 50th anniversary of the Sweetheart of the Rodeo record.

Stuart—who began his professional career at age 12 and subsequently played mandolin and guitar with Lester Flatt and then Johnny Cash—has long been a personal and musical advocate for his precursors.

In 2017, he curated an exhibition at the Grammy Museum. Marty Stuart’s Way Out West: A Country Music Odyssey presented “the story of a transformation in country music through the lens of the American West.”

Indeed, Stuart continues to strike a fertile creative balance, embracing the sounds of his forbearers while striving to remain at the vanguard of his contemporaries.

He explains, “What drives this band’s mission statement at any moment is a blend of current inspirations, along with inspiration from the past and whatever needs to fill the hole in my heart for the future. That’s the job on the table.”

Ever since Stuart founded the Superlatives in 2002, they’ve been up for the task at hand. The aptly named group features guitarist Kenny Vaughan, drummer Harry Stinson and, since 2015, bassist Chris Scruggs.

Stuart hails their contributions in the boldest of terms, proclaiming, “I stand in the middle of it all night after night, and I never cease to be amazed by the level of brilliance that surrounds me.”

You continue to take an active role as a country music curator and historian. When it comes to making new music with the Superlatives, to what extent does that mission inform the process?

I’m no different than I was when I was nine years old and I started my first band in the backwoods of Mississippi. It seemed like all the British Invasion bands had correspondents in that part of the country. When there was a high school dance or some kind of event, there was always a bunch of kids that had mop-top haircuts and played British Invasion songs on cool guitars. But I noticed that there were no correspondents in the backwoods of Philadelphia, Miss., for my old heroes, who were Johnny Cash, Porter Wagoner, Merle Haggard, Buck Owens and the like.

Our radio station played everything. They came on with country music in the morning and, at noon, they played gospel music for an hour. Then it was Top 40 and rock-and-roll in the afternoon, soul in the late afternoon and easy listening. I was a sponge and I loved everything, but it was country music that touched my heart the deepest—all forms of country music.

I started my first band with my two buddies, thinking that we needed to be singing songs that represented those people. It was a self-appointed mission, but it was what my heart loved the most because I’d hear country songs and look outside the window to see who they were singing about.

It’s no different tonight. I still feel like I’m a bit of a correspondent for my heroes, past and present, along with what we do.

I shut down the very first Superlatives rehearsal and said, “We need to talk about this. Everybody in this room has been there and done it 40 times. We’ve all got $200 in two different banks, we’ve got the girl of our dreams, cool instruments and cool cowboy boots. So let’s talk about what we believe in now.” I saw the Superlatives as musical missionaries or mercenaries. It wasn’t about chasing threeminute hits up and down the street anymore. It was bigger than that.

So with that in mind, we went to work. With that as our compass and guide, it is amazing where this band has gone in the past 20 years. That still turns out to be true with Altitude.

The British Invasion bands also made a point to shine a light on American blues artists. Was that instructive to you as your career developed?

I loved what the Stones did for Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. They took their fame and their fortune, and they put the spotlight on our old heroes. Merle Haggard was white hot when I was a kid and I couldn’t wait to see what he was gonna do next—what was going to pop out of the speakers in my stereo. But he threw me for a loop when he took his “Okie from Muskogee” fame and shined the light on Jimmie Rodgers and Bob Wills. He made two records of their works, and it was a life lesson on how to use your fame wisely.

In my case, it’s a sign of respect because most of those old heroes of mine were the master architects of this culture, and they just happened to be the people that raised me. So it’s a matter of love and honor to bring ‘em along with me, wherever I’m going.

That really came to a cool place when we did our TV show. For years, I went around asking, “Why doesn’t somebody do a 21st-century version of The Porter Wagoner Show and catch what’s left of the traditional country music culture?” Finally, one day Kenny Vaughan says, “Ain’t nobody gonna do that. Why don’t you do it?” I went, “Got it.” So we did 156 episodes of a television show on a network that allowed us to do whatever we wanted to do. [Original episodes of The Marty Stuart Show ran on RFD-TV from 2008-2014].

But it’s what Merle Haggard taught me. We used that moment to shine a light on the last of the greats from the golden era of country music. Since that show’s been off the air, I think 43 or 44 of those people have passed away in a short amount of time. So we got it just right.

I love entertaining and educating at the same time. It’s my favorite form of it all.

Your exhibit took that to another level by placing many of those artists in a museum setting.

There’s often a push for the new, next, latest and brightest thing. I have never, ever lived by a chart or who I’m told I should like at a certain moment. I’ve always believed the entire story moves forward.

As time goes on, the decades pass really fast. We forget how great certain things are, how powerful they are, how much they speak to our culture and how much they enrich our lives. So every now and then, it’s nice to have a reminder and a nice setting to go to where you can look at that stuff.

It’s even more important to go into a room and hear the music that was inspired by all of that. I think that’s a cool way to keep things moving forward— by bringing them into the now and showing how relevant they still are.

I went to work with Johnny Cash’s band in 1980 and stayed there until ‘85 or ‘86. Then I was in and out of that situation for the rest of his life. He was my old chief. I remember when I first went to work with him, I thought, “This is not the guy that made the Folsom Prison record. This is not the guy that was on the cover of Bitter Tears.” He was more Patriot Cash. He was mostly playing performing arts centers or stadiums at state fairs full of citizens who had white hair.

That’s the way it was in America. But when we would go over to Europe, I could tell, “Aha! There’s another Johnny Cash wave coming!” What I learned was that his people would reintroduce the name Johnny Cash about every 10 years as if to reseed the audience. So new people would come out and hear, “Born in Kingsland, Arkansas in 1932 to Ray and Carrie Cash…”

I saw Johnny Cash at a rock club in Boston shortly after his first album with Rick Rubin. I remember looking around and thinking that it was not a traditional country audience. It was more of a punk and alternative crowd.

I think about when B.B. King broke through, from just being a chitlin’ circuit performer to when Bill Graham was using him on shows at the Fillmore— all of a sudden this whole new audience found him.

When I was in Lester Flatt’s band as a teenager, Lester was seen as kind of a tired old Opry act but then we played the right show in Cincinnati. It was a college-buyer showcase with Lester Flatt, Chick Corea and Kool & The Gang. How about that? The next thing I knew, we encored nine times and the next day we were rock stars.

It was a similar thing with Johnny Cash because he kept on doing it. He kept making records. One day he called me out to his office and said, “I want to play you something.” Then he sang me 10 songs, just him and his guitar. Before he started, he said, “I don’t want you to speak to me for 21 and a half minutes.” I went, “Got it,” and he handed me a Coca-Cola.

I listened to him do those songs and I asked, “What did I just hear?” He said, “My new record, just me and my guitar.” I said, “Just you and your guitar?” He said, “With Rick Rubin— what do you think?” I could tell he was a little bit doubtful. I went, “Man, that’s it. That unlocks the whole thing.”

The point being, the common denominator with B.B. King, Lester Flatt and Johnny Cash is that they didn’t change anything. The wheel was turned, the setting was right, the moment was right and the magic happened all over again.

I think that’s how it has to move. If you start chasing and become something that you’re not, then even if you hit, it’s a hollow victory.

I love doing it the way we’re doing it—just moving with the heart, moving under the cloud of inspiration, trying to grow the audience and get into uncomfortable environments where nobody knows you. You have to prove it with music and guts. That’s when the good stuff happens. It’s exciting.

Jumping to the new record, can you talk about your initial connection with Sweetheart of the Rodeo and how that manifested itself on Altitude?

When I first went to Nashville, I was 13 and Clarence White’s brother Roland was in Lester Flatt’s band. I started on the circuit when I was 12 years old, playing with a group called The Sullivan Family Gospel Singers. They were Pentecostal bluegrass church-house stars, and some of their shows were at bluegrass festivals.

Roland White was one of my original mandolin playing heroes, and he was so kind. He gave me his mandolin pick, his phone number and said, “Call me sometime. Maybe you could come up to Nashville and ride along with us on the bus for the weekend if it’s cool with Lester and your family.” I went, “Sure.”

Well, I got kicked out of school at the end of that summer because I was a pitiful excuse for a student. So I called Roland and I said, “This would be a good weekend for me to come ride the bus.” So I begged my mama and dad to let me go to Nashville just for the weekend.

That weekend turned into a job. Lester offered me a job.

I lived with Roland when I first started in Nashville, and he had this stack of Byrds records. I asked him, “What is that all about?” He said, “My brother Clarence plays guitar with The Byrds.” So I became familiar with Clarence’s playing by way of that stack of records.

Not long after that, Roland left Lester’s band to go back to California. He and Clarence and their other brother Eric were going to put their old band back together. Then I started collecting records on my own.

I was living at Lester Flatt’s house, and I went to a shopping mall in Hendersonville, Tenn., and bought Sweetheart of the Rodeo. It was in the discount bin so I think I paid $2.99. I loved the record because it was a successful collision of rockand-roll, country, honky-tonk, folk and gospel music. I loved the artwork on the front. It all just had an appeal to me.

Then after that college buyer showcase, one of the first shows we played was at Michigan State University. The opening act was Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris. Then Lester played, and the Eagles were the headliners. They were on their Desperado tour.

That night I watched and played with people who brought that Sweetheart record to life. I walked onto the bus after the show and told myself, “I can see how I’m gonna live the rest of my musical life.” The old-timers didn’t see it whatsoever, but that Sweetheart record goes back that deep with me. I’ve owned it on every format.

So when Roger called and said, “You guys want to go out and play a couple of shows?” I went, “We’re in.” Chris Hillman had been a victim of the California fires and his house was in peril. So Roger said, “Let’s go help Chris.”

It was supposed to be five or six shows, and it turned into a thing. All of a sudden, everybody started winning. The audience never thought they’d see it. The Superlatives got to be The Byrds. Roger and Chris got to be Roger and Chris, and they didn’t have to put up with band members. [Laughs.] They got to drive off and go to the hotel at night. It was one of the most magical musical environments I’ve ever been a part of. Then on top of that, we also played a bunch of shows that year with Steve Miller Band and Chris Stapleton.

So I was in the presence of all these gargantuan songs. But those Sweetheart shows were the heart and soul of it all. I played Clarence White’s guitar alongside Roger’s 12-string. Chris Hillman played some bass and, of course, there were those harmonies.

So while it was not intentional, I have no doubt all of that followed me to the blank page and became songs with those kinds of sounds around them. I don’t think anybody wanted to stop. We could have kept going for two years with that tour. So I think one of the ways that I prolonged it was that I took a little of it to the studio with me.

***

Looking back, was there a particular song in the batch that initially felt that way to you?

“Sitting Alone”—I heard a 12-string riff opening it up the minute I got through with it. I heard myself playing a Clarence White solo in the middle, and I heard those kind of harmonies that Crosby, McGuinn, Hillman and Gene Clark did.

I wasn’t trying to rip it off. It just felt that would work really good on this song. We started knocking it around during soundcheck and it was fun. We were like teenagers with our first Fender guitars hoping girls would like us all of a sudden. [Laughs.] I think it went back to that part of our lives.

To what extent do you feel there’s a connection between this album and Way Out West?

“Time Don’t Wait” on that record certainly had a Byrds feel to it. Let’s back up a bit before the Way Out West record, even before the 156 episodes of the TV show. We had made a record called Souls’ Chapel, which was shining a light on The Staple Singers’ kind of Mississippi Delta gospel music. It was a vanishing form. We had also done this record called Badlands: Ballads of the Lakota that shined a light on the culture of the Native Americans out on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

We were being invited to come into other people’s worlds and we were honored guests, but I remember coming up onto the front of the bus one day and saying, “We don’t have a place to drive our sword in the dirt yet and go, ‘This is who we are.’”

Then we did those TV shows and we made three or four records around the sounds of traditional country music, which was vanishing. We made a really hard issue out of that.

After all that was kind of “mission accomplished,” with Way Out West I thought we did a pretty good job of turning the wheel just a little bit to get us into the next creative chapter of this band’s life. I knew after those songs were written that this was not a Nashville record. I knew it was a California record.

So I called Mike Campbell because I thought he would be the perfect host to show us through the California boulevards, canyons and desert scapes and get us to an authentic place. Way Out West was the toe in the water to get us beyond the traditional country-music zone.

“Time Don’t Wait” turned out to be one of the anthems on that record. I didn’t see it coming. I remember driving down the interstate in Nashville one day and pulling over because the words were coming so fast. There were cars honking at me and that kind of stuff. I didn’t have much to write on, so I was writing on whatever I could find in the car. There was a semi-truck that almost ran over me when the line “A thousand angels dropped matches that lit up the desert sky” came flying out and I thought, “Well, if I get killed, that’s a good line to go out on.” [Laughs.]

When we finished Way Out West, there were three or four songs left on the table that we didn’t use and there were sounds in my mind that I wanted to keep going on.

I thought Altitude kind of picked up where Way Out West left off. It was like, “Here’s another chapter to this.” It felt like an authentic place to go beyond Way Out West.

Altitude is interspersed with instrumental vignettes. To what extent would you say there’s a narrative throughline in the record?

I don’t know that there is with this one. I’ve done records that were highly conceptual—The Pilgrim had a railroad track and a pecking order for those songs. I don’t know that this one really has that. I just wanted it to entertain and flow. I wanted it to feel like you’d hung out with me and the band and we took you on a little ride.

Instrumentals are a big part of this band. Every one of us grew up listening to The Ventures or The Shadows and loving those kinds of songs. As a matter of fact, the next thing up on the docket—it’s already boxed and bowed—is a 20-song, cinematic, groovy surfy record of all instrumentals.

But if you go back into the Superlatives’ catalog, instrumentals have been a part of the vocabulary since day one. Everybody in this band plays their tails off, so I think it’s a cool way to get things going. People come to see this band to hear picking, and that’s a pretty cool thing to me.

What led you to play sitar on “Space?”

Well, country and Eastern music, why not? [Laughs.]

I think the first time I ever heard a sitar was on a Joe South song called “Games People Play.” It was an interesting sound. Again, I’m a child of the ‘60s and it was a sound that session guys in Nashville used from time to time. In the ‘90s, my buddy Jerry Jones built one and I bought it. It was one of those things that I would pull out every eight or nine years and use it on one song.

We also were doing some shows with the Steve Miller Band, and Steve had this really beautiful song that he did on a sitar.

I remember, one night, we were leaving the concert grounds and traveling down the freeway of Northern California and “Space” just fell out of my pen in about five minutes. Then I thought, “Well, what if we were to put a sitar on that?” It was that simple. I think the sitar is like a lot of other things where if it’s used in a tasteful environment, then it has a good effect. It was also a sound that we had never featured before inside the Superlative camp. So it was a new voice to add in there.

Circling back to Johnny Cash and his evolving audience, over the past few years you’ve played a number of events where Relix readers have had a chance to see you in action. For those who haven’t done so yet, can you talk a bit about the Superlatives and all that they bring to bear?

The Superlatives are, first of all, world-class people. Second of all, they are world-class musicians and, third of all, they are professors in their own way.

Kenny Vaughan is, hands down, one of the brightest guitar stars out on the trail these days. The first time I saw Kenny, he was playing with Lucinda Williams. I think they were doing Austin City Limits—this would go back 21 or 22 years now. After about two songs, I forgot to watch Lucinda—I apologize Lucinda. [Laughs.] I just watched Kenny the whole time. He had a Luther Perkins quality about him as a character. But as a guitar player, I could tell that he could play anything that came his way.

Harry Stinson and I made records together. He played on some of my original country music hits. Harry came to my attention when Steve Earle did his Guitar Town record—it kind of reset and reshaped things, and brought twang back to Nashville in the late ‘80s. Harry sang on a song called “Hillbilly Highway” with Steve Earle, and Richard Bennett played the guitar. It’s one of the greatest records I’ve ever heard. So I went and found Harry and we started making records together back in those days.

As for Chris Scruggs, the name says it all. He’s someone that Harry, Kenny and I have known since he was just a little guy. During our TV show days, when we would need a can-do anything guy, we’d call Chris Scruggs. He had worked with a band called BR549 and he had been out with Michael Nesmith and some other people. Chris is also one of those guys who can tell you what color shirt John Lennon was wearing on the third take of the fourth day of the Abbey Road sessions [Laughs.] But all these guys are that way. I’m just spoiled to death.

We’ve been finding our way out of the traditional country music world and into this whole new ether that we’ve been in ever since Way Out West. We’ve made a point to go to places where people may not know exactly what this is all about or who exactly this is. I kind of go back to the statement that Cowboy Jack Clement made about Johnny Cash one time. He said, “There’s two kinds of people—those who know Johnny Cash and get it and those who will.”

We’ve been to DelFest, Hardly Strictly Bluegrass, Suwannee Spring Reunion and others. We’ve also played alongside Billy Strings—I love seeing what he’s doing for the world of bluegrass music.

I feel like the Relix audience is our absolute home audience. The beauty of that audience is that they’re true musical people. So once everybody comes around and checks it out, that usually turns into repeat visits. It’s just a matter of getting all the way into the room with everybody for consideration.

Kenny Vaughan’s assessment of our band and the inside of that world is: “We’re the coolest uncles anybody could ever hope to have. We have better stories than everybody else at the dinner table.” I think that’s a pretty good assessment.