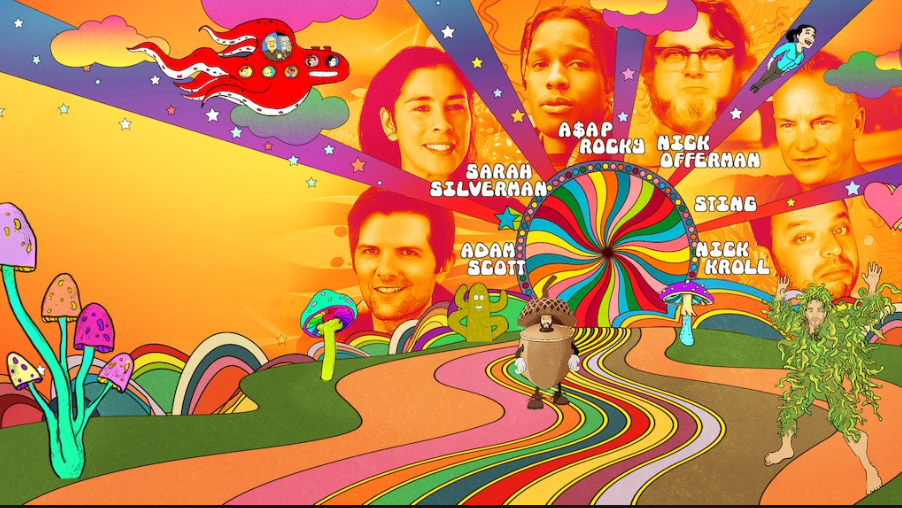

Adventure Time: Director Donick Cary on ‘Have a Good Trip’

Donick Cary’s new documentary, Have a Good Trip: Adventures in Psychedelics, offers an

animated treatment of your favorite entertainers’ mind-altering journeys.

“Drugs can be dangerous, but they can also be hilarious.”

This line, which appears in the new documentary film, Have a Good Trip: Adventures in Psychedelics, is one way to encapsulate a movie that “explores the pros, cons, science, history, future, pop cultural impact and cosmic possibilities of hallucinogens.” The film does so via stories from Bill Kreutzmann, Carrie Fisher, Adam Scott, Nick Offerman, Anthony Bourdain, Sarah Silverman, Sting, Ad-Rock, Lewis Black, Rosie Perez, A$AP Rocky, Nick Kroll and several other entertainers. Many of these accounts are depicted via animated sequences, while others are reenacted by comedians (with Rob Corddry and Paul Scheer swapping identities, for instance).

Director Donick Cary worked on the documentary for over a decade before Netflix finally released it in May. During the span of the film’s production, Cary—who began his career on Late Night with David Letterman, advancing from intern to head writer before moving on to The Simpsons and later creating Lil’ Bush— spent his days as a writer and producer on TV shows such as New Girl, Parks and Recreation, Silicon Valley and A.P. Bio.

“When I look back on the 11 years it took to make this film, I suppose I could describe it as a really fun hobby that I worked on whenever I had a little downtime,” Cary reflects. “If Carrie Fisher said, ‘I can meet you on Tuesday at 4 p.m.,’ or Sting said, ‘Let’s do this next February in New York,’ then I’d say, ‘Great, put it on the calendar.’”

Cary ultimately conducted over 100 interviews, enough for multiple films, or even a series. “With some of the speakers, like Sting, we’d have enough material for a half hour,” he explains. “We could easily make 30 episodes. We’re still figuring everything out. This came out of the comedy world first, but we also wanted to share real stories and perspectives rather than just running to the freaky unicorn ride. In our minds, there easily could be another series where you focus on one or two storytellers and dig into the topics that they bring up. There’s an ongoing dialogue happening these days around these issues.”

What initially prompted you to make Have a Good Trip?

It all started 11 summers ago at the Nantucket Film Festival. I’m on the board, and the wonderful thing about the festival is that it’s not a sales place. It’s really a place where you can hang out, talk about ideas and watch documentaries. I was at a bunch of movies with Ben Stiller, who is also a board member. He summered there as a kid, so I have known him off and on over our careers. Fisher Stevens was also at the festival that year, releasing the movie The Cove, for which he went on to win an Oscar.

The three of us were eating together in a lounge in between movies and ended up in this conversation, just sharing psychedelic stories. Ben actually shared his experience at a storytelling night that they have there as well. So we were all talking about our trips and I was like, “This is so entertaining—just sitting here over lunch, swapping stories about some of the most intimate things that the brain reveals.” And I was like, “Fisher, you make documentaries. Ben you know everybody and get this weird mix of big issues and comedy. What if we just made a doc?” And it was green-lit there. They were both like, “Yeah, let’s do it.” So I went to Ben’s company a few months later and formally pitched it to his team. And Fisher’s company, Insurgent Media, was on board to put up the money and help get it made.

It seems surprising that Ben agreed to be involved because his story underscores that he isn’t an advocate for psychedelics.

A number of things happened over the course of the 11 years we worked on this. When I started, this was a lot more like The Aristocrats [the 2005 documentary in which comedians share different versions of a famous joke]. I thought, “OK, we’ll line up a bunch of funny people and get funny stories. Then, we can use animation to bring to life things like dragons and the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man. The original goal was to get some funny stories together.

A lot of Ben’s comic persona comes out as a neurotic guy who gets stuck in a nightmare situation, and this was a big version of that for him. And I thought, “This is great because it actually gives us one edge of this movie—that psychedelics are not for everybody. They shouldn’t be done cavalierly. You shouldn’t take psychedelics and wander the streets when you’re 16 if you don’t know what the hell you’ve just put in your mouth. That’s not a smart decision.”

But what also happened is that, once we started talking to people, my perspective changed. It’s like cosmic thinking. All these things different things—that otherwise might feel like clichés—can feel profound when you’re on a hallucinogen, like, “Oh, we’re supposed to love each other.” It is really powerful to understand that we’re all connected in these profound ways. But to say that same thing on a greeting card is just not powerful. We mostly use the greeting card version in our regular life, but the other one is possible if we kind of agree that’s how we’re going to feel it.

Given the dichotomy that you’ve just described, was it challenging to jump back and forth between the documentary and your daily life?

I will say that one of the weirdest parts of this was that, as an interviewer, when I’d sit down with these different people my brain would start to slowly tune into this other way of seeing. As I would hear these stories, I would empathize and get into their headspace. It was very strange to spend four hours with Carrie Fisher talking about what her brain does on acid and then walk out and go, “I have to pick up my kids at school” and go about this other reality that we have.

Drugs aren’t a big part of our life, so my kids aren’t saying, “Every Friday, dad and mom sit in the backyard and stare at the leaves while they’re on psilocybin.” What I hope they’ll say about this film is that I made a funny movie that is crazy and wild, but also takes on some bigger ideas. Otis is 11 and Amadi is 17, so they’ll get different things from it.

It’s like watching The Simpsons. There’s a lot of people who are like, “I don’t want my kids watch it. There’s lots of stuff in there.” And my response is, “Well, they’ll take what they need and if, by the way, they see a Simpsons episode that has something controversial, then let’s talk about it. They’re going to learn something.”

We had Ben’s story early on, which is a cautionary tale about how things can go wrong. I knew it would be a good counterpoint; I figured most people who were going to say yes to being in this movie were going to be pro-psychedelics or pro-drug. And I knew that some of these stories might come off as a party. We wanted to be careful with that. The question was, “How do make a balanced, funny movie that is somewhat pro-psychedelics but is also nonbiased?” I want my kids to see all the sides, whether it’s Catholicism or psychedelics or The Beatles. They should have everything before them and then figure out how it relates to their own life.

Sting’s account embodies contemplation and meditative self-discovery through psychedelics. How did you come to interview him?

We hired a booker and put the word out to bug everybody. It was amazing. On any given week, we’d get weird responses like, “Ozzy is in, but he can only do it next June. Susan Sarandon wants to talk to you about her experience with Timothy Leary and see if it fits. The Buzzcocks can do it when they’re on tour.”

Sting was one of those interviews that came as a surprise. We were told he was in, and the only date he was available to do it was in New York.

So we went to his apartment, which was on Central Park West at the time. One wall was full of all these windows, with views of Central Park, and another had all these beautiful Basquiat paintings. In the middle was Sting and I was like, “What are we getting into?”

There was no pre-interview, so I had no idea how much he’d utilized psychedelics to help him stay in touch with who he is. Once he started talking, I was like, “Sting is like the best. He’s got it all figured out.” He’s used psychedelics as a tool. He talked about helping break down his ego at different times with celebrity, fame and all these things that aren’t necessarily normal human experiences.

He’s used this tool to help him navigate. He’s also done incredible work for the environment and I think he relates a lot of that back to the connection he’s felt through psychedelics.

He started talking about all these different channels where psychedelics had an incredibly positive influence on him. He’s thought a lot about it and he’s a very smart, articulate, conscientious student of what he gets into. He said some really powerful things and touched on what Timothy Leary was trying to do before all that stuff got demonized in the ‘70s and became part of the drug war.

This was probably at the midway point. And it really was the moment where I was like, “We might be on to something bigger than just funny stories.”

He spoke about doing the work afterwards. If you take psychedelics just to get fucked up, you’ll get fucked up. But if you take them with an intention, then they can have a lot of useful applications.

A realization that could take years of therapy and years of meditation—or years of common sense and hard living—can happen in an afternoon. It can propel you to look back down on something from a new angle.

Even so, the film never shies away from the absurdist humor that often accompanies hallucinogenic experiences, like when Carrie Fisher encounters a misbehaving acorn.

At the beginning of our interviews, I was thinking, “I’ll get 20 great stories and then we’ll animate those.” Some people like Anthony Bourdain are great storytellers. He was able to just sit down and offer a clearly crafted account about what had happened to him. But most people think, “I’ll talk about my experience with psychedelics—that could be fun.” Then you sit down and, as Carrie explains in five different ways, there’s no orderly story that happens. It’s a dream state and a mishmash of images and revelations that don’t necessarily connect in the ways that we, in this reality, tell stories.

So I was starting to get very nervous by like my 20th interview that I didn’t I have any stories to animate or reenact. I just had a mishmash of amazing impressions. Carrie’s story was a little version of all of that. I talked to her for a long time and she told a hundred fragments, but no one story that made sense. But when we got to the misbehaving acorn, I was like, “Finally! Now we have something that I can bring to life.”

In addition, you have a story involving Princess Leia, a not-so-secluded beach and a tour bus.

That was a late addition. About a year and a half ago—once we sold it to Netflix—I realized that I needed to organize this thing. I had a hundred interviews, and I needed to cut it down to between 10-20 main storytellers, and then use a few of these other people as a Greek chorus. If I used all the interviews, then it would be too many points of view. The thing that weirdly helped was seeing the Coen Brothers movie The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. In that movie, they show a story card, tell that story and then they start another one. And I was like, “Let’s just do that.” I started to cut stories together that touched on slightly different things and gave each of them a title, like in that movie. Then everyone ties them together with these other points and tips.

Along with the actors and comedians, there are quite a few musicians in the film. Was this your intent from the start?

When you throw out a message to the creative community and ask, “Who wants to share their acid trip?” not a lot of people are like, “Oh, yeah, I’ll put my face on that.” It can be a little dangerous to talk about that stuff for people who make family movies, people who do Disney movies or people who sell their products to China.

But I found that the odds are higher in the music community because it’s not as demonized. If you’re a musician—especially a musician that came out of the ‘60s or has some through line with that—then it’s not that big a deal. There’s a natural hand-in-hand going on there. Music has not only been a big part of my life, but also a huge part of psychedelics forever.

I did a great interview with David Crosby—that isn’t in the film—where he talks about going to a Doors show. Then we ended up getting John Densmore, who talked about doing acid with Jim Morrison. We also had a great story from Pamela Des Barres about Jim, and I started to have this whole hour of Doors tripping stories from all these different perspectives.

But then I felt that I couldn’t cover psychedelics without the Grateful Dead, and I had so many of those stories as well. The Dead have created an atmosphere that allows for a lot of these stories to happen. I have an amazing one from Brett Gelman that I’d love to animate one day. Steve Agee has a long story but only the end of it appears in the movie. He wasn’t a fan—he was a punk-rocker who received a free ticket and got dosed by accident. David Cross never loved the Dead, but loved going to shows because it was a place where he could experiment. I felt that was an interesting take on how the community makes room for people who don’t even like the heartbeat of the scene.

So we got Bill [Kreutzmann], who was able to speak very succinctly. Plus, he’s just a great storyteller with a sparkle in his eye. He told a really funny story about eating Kentucky Fried Chicken with the band in Golden Gate Park, which we ultimately didn’t have time for. They were tripping, eating chicken and putting it back in the bucket, and then trying to re-eat their chicken while it was morphing. We’ll happily do a sponsorship with KFC and bring that one to life. [Laughs.]

It felt important to have someone with his gravitas in this space say that you can do too much and admit that he has made mistakes. So he brings some sanity to it. Even within the Dead community, there’s a level of caution and awareness.

At a certain point, when I got into the editing room, I realized we couldn’t do both The Doors and the Dead. We also had Donovan, and we had stories about Hendrix and The Byrds. That could be a whole different documentary.

Although the members of Yo La Tengo don’t appear in the film, their music supplies the soundtrack. How did that come about?

There are a hundred different feelings in this film because some of the trips are revelatory, some are terrifying and some are just funny. I began to think about how we could bring all those feelings to life. Also, some of the stories are from the ‘70s, while others are from 2010. What I didn’t want to do was slam a whole bunch of acid-rock from the ‘60s in there. The vibe is very different for each story; we really needed a composer who could morph and blend, so I thought of Yo La Tengo. I’ve been friends with those guys for a long time.

The first project we did together was an episode of The Simpsons I wrote called “D’oh-in’ in the Wind,” where Homer finds out he has hippie parents; I asked if we could do a trippy version of the theme song for the closing credits. I suggested Yo La Tengo, and everyone was cool with it, including Matt Groening. We had them do The Simpsons theme in the style of The Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows.” I love their music and, years later, I did a couple of very trippy animated music videos for them, including for “Ohm,” where I connected with their more psychedelic side.

Then we thought, “What if we just use their catalog?” I had a great music supervisor, Kim Huffman Cary. [His wife— they met when Donick was head writer on the Late Show with David Letterman, and Kim worked with Paul Shaffer.] She sat down with the library and found things that captured the right mood when we’d ask, “What is a great guitar solo that sounds like Anthony Bourdain freaking out?” She also did an amazing job of picking selects. We also knew we wanted some music to connect the different sections of the movie. “Moby Octopad” became a theme as we started to build this Greek chorus. And it, hopefully, makes the movie feel unified, even if it is really just all these little short films.

So Kim really did a huge amount of lifting—just listening to the catalog and going, “All right, here’s 85 percent of the movie that can be scored just from their music.” Then, the band listened to what we chose. There were a few places where we’d say something like, “I wish there was a version of ‘Moby Octopad’ that felt a little more Grateful Dead-y. Do you guys have anything for that?” And they gave us a few recording days, where they just went in and modified things—added some guitars and stuff like that.

Did you have an audience in mind as you were making the film, and did that audience change at all during the process?

We had to gut-check that quite a bit because we started with this idea that we wanted this film to be fun and funny. But, particularly over the past few years, an interesting conversation started to materialize. Michael Pollan’s book [How to Change Your Mind] came out and helped lead to a more mainstream discussion about treating depression and post-traumatic stress disorder and trauma. So I started thinking that we’d made a version of Michael Pollan’s book, but with celebrities and comedy.

So we started by saying, “Let’s make sure it entertains fans of Sarah Silverman, Adam Scott, Nick Kroll and the indie comedy community.” But then we shifted to, “Let’s also make something that can resonate with people who are open to talking about new ideas.” I kept thinking of my father-in-law and whether he would enjoy it. I think there are parts where he’d say, “That’s really funny,” and parts where he’d say, “That’s really crazy.” But he’ll take the things that he likes from it.

If there’s one thing that this movie advocates for, then it’s rational conversation. My thought was, “Let’s not just scare people or dismiss things. Let’s talk about this for real.”