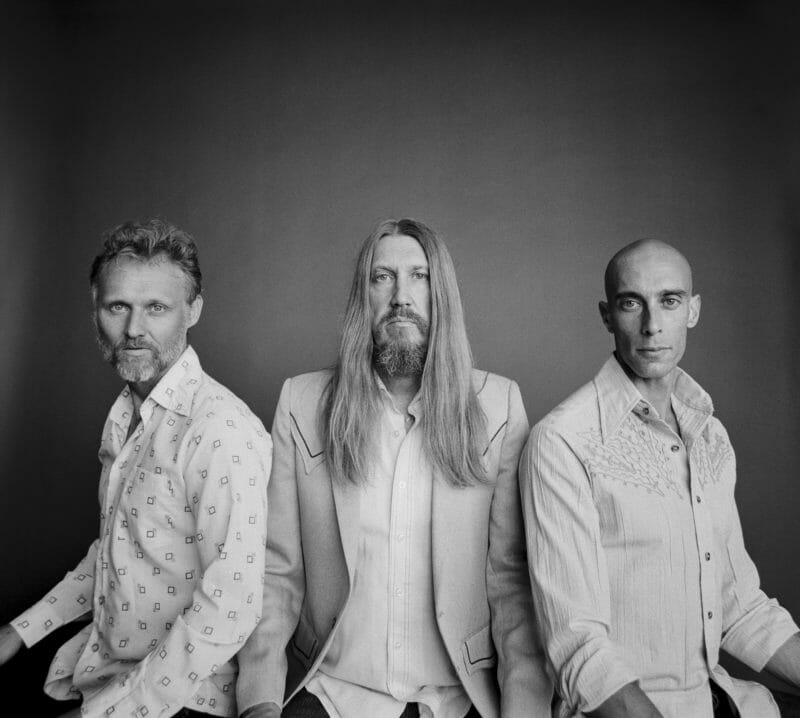

The Wood Brothers: A Little Bit Sweet

Avant-jazz journeyman Chris Wood surprised even his most ardent fans by pulling off a successful second act as a Grammy-nominated Americana troubadour with his older brother Oliver. But, almost 15 years after dropping their initial EP, The Wood Brothers still know how to improvise.

As it turns out, the key to the Wood Brothers’ latestcreative shift had been there all along—improvisation. “We had acquired a building that was going to be our new studio and set it up just enough to get things up and running,” Chris Wood says. “We started jamming and recording—without thinking about making an album. It felt so freeing to play and explore in the new space. After we recorded it all, we realized that these improvisations seemed like the beginnings of new songs.”

It’s a late November afternoon, right before Thanksgiving, and the 50-year-old, Nashville-based bassist is surveying the summer 2018 sessions that eventually resulted in The Wood Brothers’ seventh full-length studio project, Kingdom in My Mind. The album, which dropped in late January, arrives around the 15th anniversary of the band’s official formation—and nearly 20 years after the bassist, who was then best known as one-third of the genre-defying jazz combo Medeski Martin & Wood, reconnected with his older brother, singer/guitarist Oliver, onstage in WinstonSalem, N.C. And, in many ways, it took Oliver and Chris all those years of channeling the kinetic energy that only siblings possess—as well as the divergent musical paths they explored in their previous lives—to find their way back to free-form jamming.

“Our engineer buddy Brook Sutton lost the lease on his place, so we decided to all go in on renting a building that would become our studio, a rehearsal place and a home for our touring operations,” 54-year-old Oliver adds a few days later while on the road in Austin, Texas. “We rented this building, which had been used as a dance studio, and we put several months into cleaning it up—giving some sound treatment to the big echoing room, wiring up the place and customizing it. It’s still not fancy by any means, but it’s highly functional and we put a lot of passion into getting it together.”

The Wood Brothers, whose current lineup also includes multi-instrumentalist Jano Rix, culled all of the source material for Kingdom in My Mind from five different sessions, stretching from that late-summer 2018 turning point to January 2019. Then, the trio wrote over those stream-of-consciousness moments, using their raw tracks as the inspiration for a set of new, boundary-setting, cosmic Americana songs. Several cuts on the LP feature actual first takes, which were then edited together and fleshed out with lyrics and overdubs.

“We always tried to maintain that feeling that we had during the original session,” Chris says. “We were inspired by the freedom of not having any songs and seeing what happens first, musically. More often than not, when we write a song and try to come up with the music for that song, we don’t get to utilize all the things that we can do.”

Chris notes that the approach, while new to this band, harkens back to some of his favorite recordings—from the genre-defining jazz units he studied in school to James Brown’s off-the-cuff vocal raps and Talking Heads’ African-influenced, rhythmic, New Wave masterpiece Remain in Light.

“Talking Heads just jammed in the studio and created interesting music, without thinking about writing songs,” he says. “Then, David Byrne rented a car and took that music on a road trip. He listened to the radio and talk-radio preachers, and he started coming up with the lyrical content that went over these pieces of music that they had created, and that was the approach. Another great example is Paul Simon’s Graceland. He went to Africa, recorded and got all this great music.”

“The main thing is that they were about the vibe,” Oliver adds, pointing out that the demos The Wood Brothers laid down swayed closer to what he refers to as “soundcheck music.” “It was more about capturing things that we would never do if we were actually trying to write songs. There are weird drum fills and guitar and bass licks that really wouldn’t make sense if we were just trying to play a song.”

During their initial summer 2018 jam, The Wood Brothers captured 10-12 noteworthy ideas and were immediately struck by the varied styles they touched on. They decided to harness that diversity throughout their process, trying out different configurations as the sessions progressed. Sometimes they isolated the bass or drums in their own room; other times, they let the instruments bleed together in the same space or tested out different acoustic and electric configurations.

Oliver credits his brother for carrying the spirit of those early beta tests through the more proper studio work that followed: “He has a lot of experience improvising and editing. If you look at a song like ‘Alabaster,’ I wrote most of the lyrics for that and then I told Chris I wanted to make it work over a certain groove. He edited it and arranged it so that it fit.”

Lyrically, The Wood Brothers also started digging deeper, honing in on perhaps their most introspective stories yet. While their words have always been personal—capturing a sense of grayness that can cloud the human experience—this time Chris and Oliver, unconsciously, started thinking more about their own lives and mortality. Chris has gradually taken a more active role in the lyric writing over the years and, completing another transition from Downtown New York jazz bassist to Southeast singer-songwriter, he has started to provide lead vocals on some tracks in recent years. Kingdom in My Mind’s name is taken from a line in one of those songs, “Jitterbug Love,” a nod to a Tom Robbins novel.

“The album title sums it up,” Chris says. “It’s really about our inner lives and how we manage living inside these minds of ours. Our brains are basically storytelling organs, and we have to figure out how seriously to take those stories and how much to identify with them. Sometimes the stories are not good, and how do you deal with that? They can make you crazy. As we get older, we learn to take them less seriously. For example, ‘Cry Over Nothing’ is this story of love and loss and all those things—what do you do about it?”

“Every time we’ve made an album, I’ve always been surprised by the thread that ties all the songs together,” Oliver says. “This one ended up being about coming to grips with the fact that we’re not completely in control of things. There are light and dark sides to everything, and the liberating thing is realizing that, rather than fight the darkness all the time, it’s OK to accept that it’s part of a normal balance.”

He mentions that the band’s unconventional approach freed them to think outside the box in terms of their song structures, too. Not only did that method allow some more “out” music—in the words of Oliver’s friend, the late Col. Bruce Hampton—to seep in between their lyrics, but it also offered those headier concepts an appropriate sonic backdrop.

“A lot of it turns into transcendence,” Oliver says. “‘Alabaster’ is certainly about empowerment in the face of real-life struggles. But there is a light at the end of the tunnel. As long as you can acknowledge it and talk about it, you can come out feeling happy and even empowered at times. Nobody is perfect. There are a couple of songs where the idea is to be as happy as you can be while you’re on this planet. But I sure wonder about what happens after that. Even though I’m going to try to be as content as possible, I can’t help but have some faith [in something] that goes beyond our life on Earth. To me, that’s a lot of the balance.”

“I just turned 50—if you’re on this planet long enough, you’re going to experience some very challenging situations, where doing the right thing is not obvious anymore,” Chris says. “When you’re young, you have this idealistic idea about what’s right and what’s wrong. And then you’re eventually in a situation where you don’t know what’s right and wrong anymore. Either choice you make is going to cause you or other people lots of pain. That’s when you really understand how complicated life can get. My brother and I are in different parts of that story, but we are both experiencing it. We’re learning how to accept all the pain with the sweetness. It’s like our song ‘Little Bit Sweet.’ It’s a little bitter and a little sweet. It’s amazing how easily we can end up living our whole life in our mind, and so we’re just trying to have some awareness about that.”

***

Chris and Oliver Wood grew up in a creative household in Boulder, Colo. Their mother was a poet and their father was a biologist who had a past life as a folk singer. Both of the younger Woods gravitated toward music at a young age; Chris sang in choir while Oliver cut his chops as a guitarist. But, as they grew up, the brothers started to drift—both musically and geographically.

“When I left the house, Chris and I went in different directions,” Oliver says. “Chris went to the Northeast, studied jazz, moved to New York City and, eventually, started Medeski Martin & Wood. They’re this incredible improv group but were also really into American roots music as well as African, Latin and other kinds of ethnic music.”

Meanwhile, Oliver became a fixture on the local Atlanta scene, performing with blues-rock guitarist Tinsley Ellis and leading his own roots outfit, King Johnson. The Wood Brothers’ story really begins on May 24, 2001, when King Johnson opened for MMW at the Winston-Salem, N.C. club Ziggy’s. The guitarist sat in with MMW during their headlining set and the brothers immediately realized the depth of their musical connection. Following that fateful night, Oliver started making guest appearances with MMW on occasion and, in 2004, after connecting again at a family gathering, the Woods decided to put together a low-key project of their own, based mostly around Oliver’s original material.

At first, The Wood Brothers felt like just another one of Chris’ myriad musical outlets and seemed to exist as part of MMW’s orbit. They released a concert souvenir, Live at Tonic, in late 2005 and their full-length debut, Ways Not to Lose, on Blue Note the following year. Chris would play sets with Oliver at festivals where MMW was already booked, and John Medeski even produced their first LP. Oliver joined the trio onstage at a Bob Dylan tribute at Lincoln Center in 2006 and appeared on MMW’s children’s album Let’s Go Everywhere. But, then, things began to shift.

After years of hard touring, Billy Martin decided that he wanted to spend more time at home, and all three members of the group felt the need to explore different corners of the musical universe with other musicians.

Oliver’s upper-octave voice—which not surprisingly lands in the sweet spot between high-and-lonesome Southern drawl, Mountainous Appalachian blues singer and smokey jazz crooner— and the band’s advanced-degree spin on stripped-down country, folk and rock, naturally aligned with the Americana movement that came to define a portion of the early 21st-century festival circuit. Likewise, their tight, yet limber songs and harmonies proved to be the perfect entry point to their elastic musicality. An association with Zac Brown, who signed the group to his Southern Ground label, helped expose The Wood Brothers to an entirely new audience, too.

“When we first started, of course, everyone was like, ‘This is your side project,’ but I never would have described it that way,” Chris says. “It was just another thing that I took very seriously and was excited about. MMW were on the verge of slowing down because the guys in the band wanted to tour less and then, the universe was like, ‘Here’s your brother and he has your same job. Maybe there’s going to be a handoff here at some point.’ It was a very long, slow, busy, crazy, complicated crossfade between MMW being my main focus and then my brother and I moving to Nashville.”

“When Chris and I both moved to Nashville, that was a pretty big thing,” elaborates Oliver, who relocated his family to Music City about eight years ago. “It certainly showed a real commitment—we were going to be in the same town so we could work on music every day if we wanted to. Before that, he was in upstate New York and I was in Atlanta. It was challenging to work on music together.”

Along the way, the duo expanded their ranks to include Rix, who, the brothers note, is more than a simple drummer providing a rhythmic launching pad. “Having Jano is like adding a third, fourth and fifth player,” Chris says. “Not only is he a great drummer— whose dad played with Bob Dylan, among other people—but he actually quit drums for a while and went to the Miami School of Music and became a full-on jazz piano player, and he’s a great singer. And he can do all of those things at the same time. He also plays this thing called the shuitar, which is a shitty, acoustic guitar.”

“He’s an amazing experimenter, sonically, and also comes from a jazz-improv background,” Oliver says. “Eventually, we realized what we all love—The Meters, Ray Charles. I was always into the blues, Southern rock, Jimmy Reed and stuff like that. I got into singing and songwriting before I got with Chris. So, in addition to bringing that stuff in, until recently, I was the one who wrote most of the lyrics. We’re always finding cool ways to collaborate and put all of our strengths together.”

Though Medeski and Zac Brown continued to play different roles with The Wood Brothers for a few years, the trio quickly made a name for themselves as keen producers, too. 2018’s One Drop of Truth even received a Grammy nomination for Best Americana Album.

“The three of us can produce well together, and I don’t know if a lot of bands can say that,” Chris says. “We have enough experience doing it individually—and we have enough awareness of each other’s strengths and weaknesses—that we know when to take the back seat or take the lead. If one person is having doubts about something, or is not sure what to do next, then someone else jumps in and has a vision. People usually try to write 20 songs, go into the studio and record them all at once. Then, they get completely overwhelmed. That’s when you need a producer. We deal with that by doing one song at a time: We write it, record it, see what happens and then just put it away for a couple months and go on tour or work on another song. It’s a real democracy and that’s what I was used to in MMW.”

Oliver adds that their studio experiences have allowed them to explore different “psychological approaches and psychological pitfalls, too.”

“There are certainly ways you can psych yourself out in the studio, which is why people have producers,” he elaborates. “The last couple of records, we produced ourselves and we learned so much about what it means to give yourself perspective. A producer gives you a neutral ear, which is hard when you’re close to your own art. But the luxury of our studio is that we can experiment and we’re not paying any extra for it.”

***

Oddly enough, for players who made their name onstage, The Wood Brothers say that one of the hardest parts of the Kingdom in My Mind experience has been revamping their new songs for their live show.

“Composing songs the we way we did makes it difficult to translate them live and vice versa,” Oliver says. “Sometimes you have to add a structure here or sacrifice something there. You can be subtle on an album track because you have a captive audience. Whereas live, you might have to take out some subtleties and ‘dumb’ it down a little. You want the story to get through and the vibey, cool stuff that’s on an album doesn’t make as much sense. It’s about the atmosphere: Tonight we’re at a seated theater and last night we were at a place where everybody was standing with a drink in their hand. Sometimes, live, we’ll just strip a song that was electric down to one microphone, an upright bass and some acoustic guitar.”

However, looking forward, The Wood Brothers see their new sonic laboratory continuing to play a major role in their creative process. “We can really make our own schedule,” Chris says. “We can go in there with no real plan and just react to how things feel that day. One of the rooms is really big and you can fit a whole orchestra in there. And then there’s another room that’s a little dryer.”

Oliver says they have also used the space to work with different musicians and that Brook Sutton regularly records with other clients. “We’ve done sessions with other people,” he says. “Sometimes Jano or one of us will produce someone else in the studio. We’ll probably try to do a lot more of what we did this time, where we just go in there and try to come up with fresh music. It creates a really childlike atmosphere when we do that. And that’s an attitude you can take onstage or anywhere. Each new album is a learning experience and there’s a wisdom that has come from years of developing our own tastes. We’re just trying to make our own formula.”

Chris also hopes to work with Medeski Martin & Wood a little more this year, and the trio will regroup with longtime mentor John Scofield this summer. He mentions a recent documentary about MMW that played at the Woodstock Film Festival; they hope it will screen elsewhere in the near future. And, they are also sitting on a stack of songs that have already had an eventful life.

“Two years ago, we went to record an album,” he says. “The idea was that we were going to go to Mexico, into the jungle, and create another experience like Shack-man, which was recorded in a shack in Hawaii. And we wanted to have a film crew capture the whole thing. The day before we were supposed to fly down there, a huge earthquake hit Mexico City and the airport had giant cracks in the runways. We had to completely change gears overnight and find a new location. We ended up in the Catskills at what’s left of an amazing studio up there called Allaire.”

Though the space still exists, it was a shell of its former self and most of the studio parts had been sold off. “It was the only place we knew that was weird-looking enough and strange-sounding enough to film this thing,” Chris says with a laugh. “We just scrambled to get engineers as quickly as we could and to get everyone’s flights changed. That’s basically what the film is about. Now, we need to finish the record up.”

But, especially with Kingdom in My Mind, The Wood Brothers remains a primary focus—and for a good reason. A recent stop at New York’s recently refurbished Webster Hall was so packed that fans were spilling out into the halls and lining the venue’s various staircases to capture a glimpse of the trio. This spring and winter, the ensemble will play marquee theaters around the country— one of their sweet spots—from Oakland, Calif.’s Fox Theater to Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium. Then, this summer, they will balance headlining dates with a mix of festivals that blur the boundaries between jam and traditional string music. The band doesn’t take their newfound success for granted either, especially after so many years in the trenches. “I feel like we are lucky to have our jobs and can’t believe we’re doing this,” Oliver said between songs, when the group stopped by Relix’s Manhattan office to tape a video session.

“With every album we make, we get better—we learn more about our strengths and weaknesses, about our sound,” he admits. “There are no major expectations or disappointments; it’s just like we’re doing the next thing and staying in the moment.”

“It’s nice to grow older with someone who you can relate to and who understands the good and bad childhood stuff you experienced,” Chris admits. “It’s just been this long, slow journey. Some artists have a meteoric rise to the top; we’ve had a slow rise to the middle. Every time we go back to a town, there’s a few more people paying attention. It’s been a lot of work, but it’s been a labor of love.”