Mickey Hart: A Rhythm Devil Reflects on Athletic Rhythm Masters

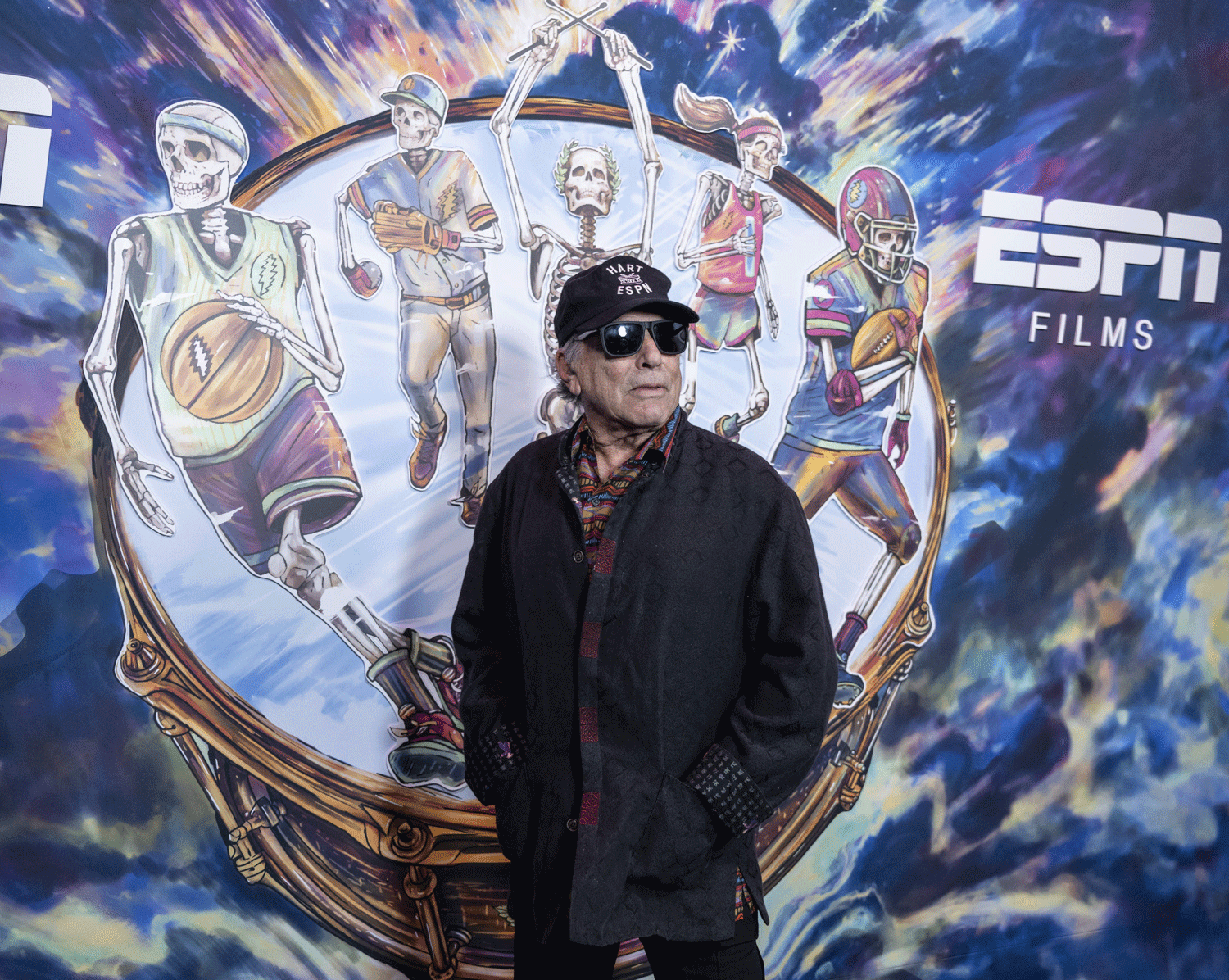

photo: Jay Blakesberg

***

Note: The following conversation with Mickey Hart appears in our current issue of Relix took place prior to the passing of Phil Lesh.

Shortly after Lesh’s death, Hart shared a powerful statement, noting in part, “Phil Lesh changed my life. There are only a few people you meet in your lifetime that are special, important, who help you grow spiritually as well as musically.He turned me on to the world’s music, gave me my first Alla Rakha record when we lived on Belvedere Street, changing forever what I thought was musically possible…His sound is indelibly embedded in my mind as is Jerry’s sound… and always will be.”

***

“These athletes all talk about the same thing in different ways. They all know how to get into the now and maintain the groove,” Mickey Hart says of the elite performers he interviewed over two years, while serving as the driving force behind a new project for ESPN Films. Rhythm Masters: A Mickey Hart Experience finds the Grateful Dead drummer, sonic investigator and author exploring many of the ideas that have long animated his musical and literary ventures.

Hart’s nuanced discussions and ongoing research not only propel the narrative, but he also created the original score for Rhythm Masters. Here, he drew on his command of the world’s beats along with a knowledge base that reflects his prior efforts sculpting sound for Apocalypse Now, The Twilight Zone and many other endeavors.

Director Torey Champagne raves, “Mickey’s introspective conversations with elite athletes, combined with his original music, has led to a unique film experience that’s meant to make you think and appreciate how music and sports unite us all.”

The participants include: Marshawn Lynch, Joe Montana, Laila Ali, Ronnie Lott, Bob Cousy, Sheryl Swoopes, Mario Andretti, Jack Nicklaus, Phil Jackson, Mikaela Shiffrin and Hart’s longtime friend, the late Bill Walton, whose description of a basketball passing through a hoop as “string music” served as an early catalyst for the documentary.

“These guys and these gals all know how to get into that same head space,” Hart expounds. “They talk about the groove just as I talk about it. They don’t play drums, but they’re rhythm masters.”

The rhythmic parallels between music and sports seem so obvious, but I hadn’t really considered them in depth until I saw the film.

Most people don’t think of it, but once you mention it, they go, “Wow! Of course!” What you might say to yourself is: “It’s the rhythm, stupid.” All you’ve got to do is look around and you see everything has its own rhythm. Anything that is alive has two things—there’s a light and a sound. It’s visual and it’s sonic. You can make sounds—the sound of the moon is very easily translated using radio telescopes and science called sonification, which changes form from radiation into sonics.

There are all kinds of ways to look at rhythm. The rhythm of the universe is the first thing you should look at. The beginning of time and space is where the story begins. That’s part of what’s in my books. This is the real science and to inform a lot of people about this very thing is rewarding to me.

It’s not necessarily a sports music and sports-rhythm film. It’s about the rhythm of things. I just use sports as a perfect example of rhythm because without rhythm, there could be no sports. It’s an obvious rhythm thing. Everybody knows there’s a rhythm in running, there’s a rhythm in swimming. But then you can point out that everything has rhythm.

All sort of jobs, all sorts of things, take rhythms. If you don’t use rhythm, you’ll bump into yourself and have chaos. Then, unless you can reform again and make rhythm, you lose.

One of the appealing parts of this whole thing is that it talks about the primacy of rhythm because rhythm is the basis of all existence. The bottom line here is the vibratory universe.

People can also start thinking of their lives in rhythmic terms. For instance, if you have a disagreement with your wife, do you think of it that way? More than likely not, but if you do think of it in rhythmic terms, you can say, “OK, we’re out of rhythm. Let’s get back in rhythm. Let’s get back in our groove.”

That’s how I think of the world. I have a pretty happy existence in my rhythmic world because I play a rhythm instrument. So, obviously, I’m more attuned to the rhythms of nature, the rhythms of cultures, the rhythm of my drums.

If you’re not getting that spiritual hit, that meaningful hit with the things that mean something in your life, then you might think about how to get back in rhythm. If you’re not enjoying your work and your life, there are ways to make that rhythm right for you.

Like Mikaela Shiffrin pointed out, it’s not like a steady beat, it’s more like a feeling. Life is a feeling and you can think of all of it in rhythmic terms, since the universe was birthed in rhythm, and without rhythm our brains, our hearts, our lungs, our eyes and our ears couldn’t function. It’s all rhythm.

The brain is rhythm central. It’s just that simple. We are rhythm machines. We are multidimensional rhythm machines embedded in this universe of rhythm. If you think of it in those terms, it makes sense.

Had you been contemplating this project for some time?

I would say it goes back to my love of rhythm, which began as a boy. I was born to drum, so it goes back to that. But I started thinking about it even more when I was writing the books Drumming at The Edge of Magic and Planet Drum, where I investigated the rhythms of the whole globe. Of course, it’s also stellar—the grooves of the universe, the beginnings of the universe, the sonification, even the tectonic plates. I’ve studied all of that in scientific terms as well. You could say I’ve got a Ph.D. in rhythm. [Laughs.]

So it’s a very natural thing to me. I always think in rhythmic terms. As a kid, I used to count my steps—up the steps, down the steps. Each little crack in the cement was another place to step and to count. So counting became everything to me, and that’s about time, and time is about rhythm, and rhythm is about existence, just being a Homo sapiens.

Then, of course, there’s my studies with George Smoot, the Nobel Laureate who discovered the cosmic background radiation, which was the afterglow of the Big Bang. Studying all that science just informed my education on the totality and primacy of rhythm.

It took over two years because I had to interview all of these magnificent rhythm masters. Phil Jackson and I were friends. We knew each other and, of course, he’s the great Zen master. He came off in the movie just perfectly. He explained that if you hold onto the ball for more than two beats, the groove is lost. The rhythm is broken. So Phil lays it out perfectly.

I already knew that these athletes were rhythm masters and that, if asked the right question, they would have amazing answers, and they would all be in rhythmic terms you could understand.

The score that you’ve created not only reinforces the narrative but is also compelling in its own right. There’s a sequence with Marshawn Lynch where you use hand drums in a way I hadn’t previously heard in a football context. Can you talk about the process of creating the music for this film?

I know how to make music fit image and image fit music. I’ve worked in that field quite a bit, from the Twilight Zone. I was the sound designer and music director of that, and I learned how to make all these different sounds and play to these images. Of course, I also worked on Apocalypse Now and the Tupac Shakur movie [1997’s Gang Related, starring Shakur].

It’s something I really like to do and I feel at home doing that. In this movie, I did it because I know about sports and I know the music that had to be made for it. Then you get down to the film and you’ve got to make it match.

With the Marshawn thing, I knew I had to make it sound hard. Marshawn’s the Beast, but what a spiritual person. These people talk in the spirit world, they talk in the mystical because that’s what happens when you combine music or sports and the zone.

So these guys and gals are talking the same language as any musician would talk, except they run and jump and we play one instrument or another. They talk about the spiritual payload of these rhythm-based sports—the essence of them. They talk about having ecstatic feelings.

Marshawn, he walks the field and blesses the field. He goes around the goal post one way, then he goes around and blesses the field the other way. He even prays for the people he’s about to hit. It’s an extraordinary story and he’s a serious rhythm master.

To hear Mario Andretti talking about racing a vehicle that’ll kill you at 200 miles an hour as if it were a song was something else. When he said that vibration is a song, I went, “Wow, Mario, absolutely!” I knew that, but I’m not Mario Andretti.

Bill Walton did the same thing with a ball going through a net. He called it string music. So all these people are talking in the same terms. Some of them talk in musical terms, some in ecstatic terms where trance is courted or the trance state is the holy grail— the holy grail is getting into that trance for that moment.

If you do that, you can play spontaneously without thinking. Thinking has to leave and just being in the now has to be the object of your desire. If you can get into the moment, then you can express yourself and let that expression come from some place in your subconscious because if you’re thinking, you’re behind it. If you’re thinking, then you’re in the past. That also means not being in the future, not thinking about what you’re going to do after you do this. The idea is to be in the moment and the now. You are just there and it’s happening spontaneously.

If you get in the groove and you’re in the moment, you get into that zone and then you’re connecting. Connections are the whole thing. Without connections, you’re just beating shit up. [Laughs.]

That reminds me, in the section on power, you frame power as spirit. Once again, that’s not the way that I would have thought about it, but it makes so much sense.

It’s commitment, which is what that meant. It’s how you commit, let’s say, to the beat. That’s power. If you just hit the drum, that’s one kind of drumming. The other is deep drumming where you commit completely to that and you put everything you have spiritually into it—not just power-wise, but your whole intent. You commit totally in that moment, and you can’t go back. That’s when you enter the spiritual world, the deep drumming world.

You can say the same thing for any of these guys, whether it’s Ronnie Lott or Jack Nicklaus. Ronnie Lott thinks right through you. Just like when I hit the drum, I’m thinking of the other side. Sometimes I don’t hit just the drum head. My thought goes through the drum, into the drum and out the other side of the drum because that’s commitment. That’s what all of these rhythm masters are saying. If you don’t have that connection, that commitment, then whatever you’re doing is lite—whether it’s drumming lite or music lite.

That section of the film reminded me of a story Zakir Hussain told me about a 96-hour jam at your barn. He fell asleep in the middle, then woke up and jumped back in. What are your recollections of that?

The idea was for the 14 of us in Diga Rhythm Band to do that for four days and nights. When I met Zakir, we made that record Diga and we got all of the percussionists at my barn and we went for that long. I didn’t sleep, but also I had some great Owsley acid. [Laughs.] Zakir doesn’t do acid, so maybe he went to sleep.

You always had to have an instrument in your hand, even when you went to the bathroom. You had to keep a groove because you could hear the groove from the bathroom. So that was part of the rules. You’d play a tambourine if you were in the bathroom. We played in duets, trios, quartets and then the whole band for a while. Some people fell asleep for an hour, but the groove continued for four days and nights.

Did you ever revisit that or did you get whatever you needed out of that experience and now it’s inside you?

I took a lot from that and I never did it again. It was monumental. That was endurance. Once you know that you can do it, you can do it again because it’s doable. Just like what Ronnie Lott says in the movie—it’s doable.

Zakir is used to those things. He calls them chillas—where he goes away and he plays for days. He’ll be isolated playing the drum, and he’ll start hallucinating and having visions. That’s a spiritual thing he’ll do where he’ll also see his guru and his guru’s guru, and so forth.

They go to these chillas and perform chillas when they’re young. Then you take that with you your whole life. This was our American version of a chilla.

I remember the feeling and I know I could do it again if I had to do it. I’ve never done it, though. I’ve been up longer than four days and four nights, but I haven’t played for four days and four nights. That was the only time I ever did it. It was in the early ‘70s.

You mentioned that Bob Cousy was one of your early heroes and then you finally spoke with him for this film, many decades later. How did all that come about?

When I was a kid, I used to watch TV with my grandfather. It was in black and white and there were a couple of stations that were only on for a few hours at most each night. Two of the things that were on were boxing and basketball. I don’t know if football was on TV then, but I remember boxing and basketball.

That’s when I first saw Cousy. I didn’t know anything about basketball. I knew playground basketball but Cousy was different. This was an art form. He was the godfather of modern basketball. He’d be making plays, running the ball and making these passes behind his back— just like a lot of what happens now in modern basketball.

So he was my first sports hero. I didn’t call what he did the art of basketball, but it did not go unnoticed. He was singular. I don’t remember anybody else from when I was younger doing anything like that except Bob Cousy.

Then I found out that Cousy was alive and kicking—he’s in his mid-90s. I called him and he was brilliant. It was a soulful, soulful talk. He was so full of life and energy. He was very sharp and it was a wonderful interview.

So it was really delightful to meet my idol—the guy that I thought was the epitome of what a rhythm master is.

Sticking with basketball, you pointed out Bill Walton’s reference to string music. Is that something he’d said to you over the years?

That was actually the first connection between music and basketball that I had. Many years ago, when he first described the ball going through the net as string music, I made a careful note of that. We were talking about something else and it just came up, and then we moved on to something else. But he did say that and he said it multiple times. It gave me a clue—he’s thinking of basketball as music, just like Andretti would later tell me that he was thinking of racing cars like music.

That kind of catapulted me into wondering how other people think about it. He would describe a basketball game in terms of music—how one person passes off to the other and they go down to the court and they’re making plays. It’s just like a band does. When you’re playing a song, you’re handing off, you’re getting back, you’re having a conversation. When you’re out on the court, you’re having a conversation. It’s just a different language. The ball goes through the air, you catch, you shoot, you make a basket, you win. Music’s different—it has other ways of entertaining and delighting.

The thing about Bill is that I would go watch a game when he was doing the commentating. I wouldn’t listen to him, I would just sit there and watch the game while he was out there doing it. When we’d get back in the car and we’d go wherever we were going, I’d say, “Tell me about the game. What were your thoughts?” Then he’d describe the game and it was very different from how I perceived it. It wasn’t the same game. His perception of it was so unique and in such depth that I didn’t really see the inner rhythms of it like he did.

Of course, he could also describe the whole thing in rhythmic terms, in musical terms. That was part of the impetus to make a rhythm and sports documentary that hopefully would be entertaining, delightful and informative.

I’ve heard Bill’s description of bringing the Celtics to see the Grateful Dead. What do you recall?

I remember Bill kept trying to bring all of his teammates. Some were resistant but others took the plunge and had a great time.

It was when I had a lower back issue, and they came into the dressing room while my equipment man was wrapping me up in gaffer tape so I could go up and play. Then they walked in, and Larry [Bird] had a back problem just like me, L4-L5. He was hesitant to get it operated on for one reason or another. I gave him encouragement and said, “You should have it done. Look, I’m drumming now,” and I told him it had only been six weeks or whatever it was since the surgery. I remember I had a back brace and I looked at Larry and said, “Larry, I don’t need this anymore. You can have it for after your operation.” My brace was much smaller than he would have used, so he just held it up and we all laughed.

I once challenged Larry Bird to go one-on-one, and that was a dark day for me. You don’t ever want to challenge Larry Bird to go one-on-one—or Kevin McHale, who wasted me right after Larry.

But those guys were really funny and it was delightful talking to them. They appreciated the Deadheads’ enthusiasm because Celtics fans were rabid like that, too. There was also a correlation between our fans and the Celtics’ fans because we were playing on their home turf. I also remember Larry thought everybody was screaming, “Larry, Larry, Larry!” Bill said, “No, they’re yelling, ‘Jerry, Jerry, Jerry!’ Not ‘Larry,’ but ‘Jerry.’” [Laughs.]

It was a marvelous, wonderful time.