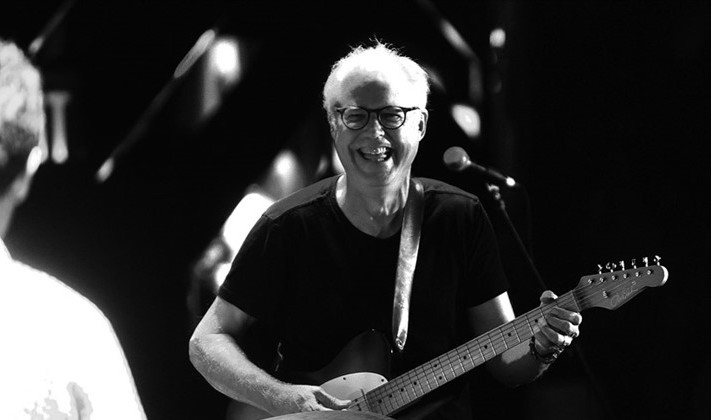

Swing Time: Bill Frisell

Dino Perrucci

Dino Perrucci

Bill Frisell’s new solo album for OKeh Records is called Music IS. The title came to him via a banjo-playing friend. “One day, he was just playing and he said, ‘You know, music is good,’” Frisell recalls.

The idea stuck. But now, after being asked if he really feels that way, Frisell is having second thoughts. “One time, I was playing with [the late jazz drummer] Paul Motian in Berlin at this little club. We walked off stage and this guy grabbed me and started strangling me. He said, ‘You are killing music!’ He was physically attacking me because whatever I was playing was disturbing him so much. See, now you’re ruining my whole theory that music is good.”

Frisell laughs but, truly, he’s got nothing to worry about. Over the course of more than three decades, the quality of music he has created has been uniformly stellar, even as he continually dodges categorization. Frisell has long carved out a place deep within the Downtown New York City avant-garde but has also recorded tributes to John Lennon and film soundtrack music. In 1999, Frisell teamed up with Elvis Costello for The Sweetest Punch—comprised almost completely of tunes that Costello wrote with Burt Bacharach—while he put his signature spin on hits from The Byrds, The Beach Boys, Link Wray and Merle Travis, among others, on 2014’s Guitar in the Space Age!

Maintaining a schedule that makes a mockery of the word “prolific,” and surprising even himself with his career choices, Frisell has recorded and performed live in so many different situations and configurations that it would take an entire issue of this magazine to even scratch the surface. He’s most often characterized as a jazz guitarist—he collaborated frequently with Motian and saxophonist Joe Lovano, as well as John Zorn, Ron Carter, Charles Lloyd and hundreds of others—but, these days, he’s just as likely to be embraced by the Americana crowd. Sometimes there might be an incensed strangler out there but, more often than not, his innovations are lauded by his considerable fan base and fellow musicians.

“Every single person could listen to the same thing and they’re all going to hear something different—no one’s going to hear it the same way.” Frisell says. “Music is powerful, but it doesn’t hurt anybody. So much stuff can get worked out in music. It seems like such a healthy thing, a model for how human beings can fit together. Just the words that you use in discussing music—harmony and conflict and resolution and counterpoint—it shows you that if we could get along in a more musical way, things might work out better.”

By his own count, Music IS is only Frisell’s fourth true solo effort and, for the occasion, he chose to stick to material he wrote himself. The music is a survey of several of Frisell’s various musical approaches, at times played straightforwardly and at other times sent through various effects and loops. Ceaselessly experimental, his style has been compared to the paintings of Jackson Pollock.

Frisell’s first album for ECM Records, 1983’s In Line, was also a solo work but, in those days, he was admittedly uneasy with the very concept of eschewing accompaniment, whether in the studio or onstage. “It was a challenge, something I had to try to figure out,” he says. “How to be comfortable with actually making a statement, letting it hang there in the air and not panicking. The air and the space and the time become part of the conversation with an audience, and whatever the energy coming back from the audience is. Gradually, over the years, I’ve gotten more comfortable with it. The first few times I did it, it really was torturous.”

Eventually, he says, “I felt like I could get off somehow playing solo; it felt like I had broken through. I want to have the same feeling when I’m playing with a group—just being able to play whatever I want at any moment, that kind of freedom.”

The still somewhat-reticent Frisell—who recently moved back to New York City after decades in Seattle because, he says, he found himself spending so much time in the jazz capital anyway—even allowed himself to serve as the subject of a 2017 documentary film, by director Emma Franz. In Bill Frisell: A Portrait, a lineup of musicians ranging from Paul Simon and Bonnie Raitt to jazz greats Jack DeJohnette, Zorn, Carter and Jim Hall pile on the praises for the Grammy-winning (and recipient of numerous Downbeat Best Guitarist awards) musician.

When he was first approached about the film idea, Frisell says, “I was open to having [Franz] around, but I didn’t know what it was going to be or what she was gonna do with it, really. It went on for quite a while to the point where I thought, ‘Wow, how much stuff do you need?’”

He’s happy with the result. “I feel like it’s really honest,” he says. “It’s hard for me to watch myself talk, but it wasn’t like the story of my life or anything like that, and it’s not chronological. It’s more trying to show the process you go through to try to write music or play music.”

Just don’t expect the film to explain Bill Frisell in any definitive way. “The reason I play is so I don’t have to talk,” he says, returning to the new album’s theme, “Music is my true way of expressing myself and it really is impossible to put into words what that is. Every time you put a name on it, the danger is that it limits you.”

This article originally appears in the June 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interview, album reviews and more, subscribe here.