Luther Dickinson: Dynamic Dead Roots

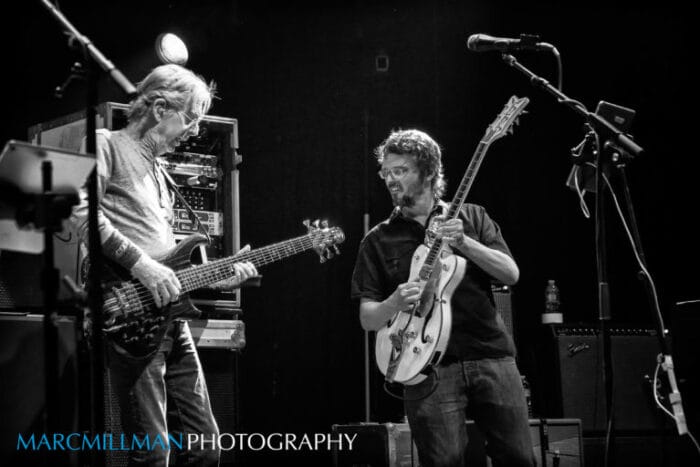

Datrian Johnson and Luther Dickinson (photo credit: Camilla Calnan)

***

Although Phil Lesh provided Luther Dickinson with his initial tutelage in the music of the Grateful Dead, Dickinson soon discovered that he had long been a student of the repertoire. Or at least a vital facet of it.

Growing up in Mississippi, as the son of renowned producer Jim Dickinson, who founded the visionary Americana group Mud Boy and the Neutrons in the 1970s, Luther had long been exposed to the Dead’s bluesier material introduced to that group by Ron “Pipgen” McKernan. The young guitarist connected to these songs though his dad’s musical endeavors as well as his own predilection for the genre, which led him to form the North Mississippi Allstars with his brother Cody in 1996.

Jim Dickinson passed away in 2009 and during a period when Luther was still coming to terms with this, he received an invitation from Phil Lesh and his son Grahame to join them for some performances at their new venue in San Rafael, Calif. The guitarist recalls, “I started playing with Phil at a time after we’d recently lost our father, and Grahame had recently started playing with his father, which warmed my heart to no end. Grahame and I became fast friends, and I would always reach out to him musically on the bandstand. We just hit it off.

“This was mainly at Phil’s place—Terrapin Crossroads—and he would delegate the Dead repertoire out to the different musicians. It was obvious that I couldn’t sing Garcia—that was way out of my range or skill set—but the Pigpen material was right up my alley. It was just like what my dad and all his friends did back in Memphis. They played psychedelic roots music. They even had a jug band acoustic alter ego. They also had an electric band with puppets and dancers and costumes, which they called their Dream Carnivals. It was like their own Acid Tests but a decade later. Memphis was behind the times, but it was really wild in the 70s. So as I was working with Phil, that was my in. I could do the Pigpen material, which led me to realize that they did a lot of blues classics.”

These are the songs that Dickinson interprets on his new studio album Dead Blues Vol. 1. The guitarist offers absorbing takes on such offerings as: “One Kind Favor,” “Who Do You Love,” “King Bee,” “Minglewood Blues” and “Little Red Rooster.” Grahame Lesh makes an appearance, as does Luther’s brother Cody along with some of their longtime cohorts.

Still, the revelation is vocalist Datrian Johnson who takes these tunes in thrilling new directions, while yet honoring their origins. Johnson and Dickinson first met via John Medeksi, after the Asheville-based singer appeared on the Saint Disruption’s debut album, in which Medeski teamed with Jeff Firewalker, who Johnson describes as “my spiritual father before he was my musical mentor.”

As Luther reflects on the material that appears on Dead Blues Vol. 1, he muses, “My rap is that in the big picture of art, if you go back to cave art or architecture or Renaissance or whatever, in the big picture of human expression, American music is a really young art form. Pop music is disposable by design and that’s great, there’s nothing wrong with that. Improvisational music is the same way, it just comes and goes and makes the world go round.

“But American roots music as an art form needs to be preserved and protected and passed on because it’s important. The language, the poetry, the melodies, the rhythms, they go back. Robert Plant can sit and tell you how this blues song actually came from Ireland and this rhythm came from a specific part of Africa. But the American experience is still a relatively young thing. It’s just so fruitful and potent.”

Since you can trace this album back to your earliest days as an artist, would you say that you chose music or that music chose you?

Man, I was born into it. I’m fascinated with musical families and the traditions and the way it passes on. But it’s not just music, you see it in sports and science, you see it in all walks of life—carpentry, artists, actors.

I don’t know scientifically how to explain it, but I really believe that learned skills and even thought processes can be passed down genetically as part of the way humans evolve and the way families evolve. I feel like it’s more than, “Oh, they have the music bug.”

Beyond that, to answer your question, I don’t remember a time when I didn’t know I was going to be a guitar player. As a little kid, I was not a natural and my dad was brutally honest. He took it very seriously as a professional musician.

I used to paint and draw, but I was not a natural musician, unlike Cody, who was a natural. So my dad was very brutally honest. He was like, “If this is really what you want to do, you’re going to have to practice.” He was right. I practice all the time. I work all the time.

I feel like having that direction, knowing what you want to do, can be a greater advantage than natural inherent talent because I’ve seen natural inherent talent actually take people down some dark paths.

How would you characterize the connective tissue between the material on Dead Blues Vol. 1 and your own creative development?

My dad was brutally honest about my guitar playing, but I did have an inherent creative process that he recognized and encouraged. For me, that can be anything from putting a band together, producing a record, writing a song, doing the dishes or cleaning up my closet.

Dad used to always say, “Trust the process.” You don’t have to understand it when you do it, but as long as you honor the process and trust the process and just move forward, it’ll work out. There are all kinds of little sidebar lessons that fit into that, but this record is a great example of that because I made this music just for fun, and then later it dawned on me that we could put the vocals on top of this music that already existed. That was a great example of just blindly creating and then letting the process lead the way.

The backstory of my relationship with the Grateful Dead and their repertoire was that my friends always tried to turn me on to the Grateful Dead in my youth. I definitely reaped the benefit—the whole southern psychedelic scene reaped the benefit—of the 90s Grateful Dead parking lot, which supplied the south with LSD whenever they rolled through. [Laughs.]

I only went to one show, though, one of the first shows at the Pyramid in Memphis. I was hardcore into Allman Brothers and Jimi Hendrix, and I’ve always been protective of what I listen to because I’m easily influenced. Then, after I left the Black Crowes, Phil Lesh started hiring me. Thank God I had heard live Grateful Dead while hanging out with CR in the back of the Black Crowes bus for about five years because he was listening to the Dead nonstop.

So it was in my subconscious. I didn’t know the names of the songs, but I’d heard it and I came to love it. I was like, “Man, this is wonderful.” I was totally in.

Thinking back to your initial connection with the tunes on the new record, how did your father approach them?

What our dad taught us and what he did with his band Mud Boy and the Neutrons was that you can look at a roots song as a structural foundation for improvisation and reinterpret it.

That’s what they would do in the same way that a jazz musician would look at a standard. The idea of playing American roots music wildly different night after night was what they loved. They never rehearsed. They would push each other to be as extreme and abstract as possible. It was very similar to what Phil taught us at Terrapin. He said that their strategy was to never play it the same way once.

Mud Boy’s approach to their own songs was very similar. Our dad recognized that, although he wasn’t a Deadhead. He was roughly the same age as Garcia, Dylan and Robert Hunter. Those cats weren’t hippies. They were Bohemian kids from the 50s into the 60s who grew up with an alternative rock-and-roll lifestyle before hippies.

I think that generation of songwriters is fascinating because they grew up listening to the radio as opposed to TV. Hunter, Dylan and my dad each had a fantastic way with words. I think that generation grew up listening to the radio and they had a mindset for lyrics.

So we grew up watching our dad and his friends play acoustic and electric, and that’s why I always wanted to be a guitar player. Our dad was a piano player, but he worked with great guitar players that I always idolized, including Ry Cooder, who is another fantastic re-interpreter of roots music.

When Phil invited you out to Terrapin, what was his advice regarding the repertoire?

He taught us the repertoire by hand. We’d get the setlist the day before or the morning of the show and we’d have that morning to shed. Thank God our father raised this with these session players. I was working with David Hood, and these musicians making the most beautiful chord charts.

When I played with the Black Crowes, I had to learn a hundred songs in six weeks. This was around the time Jimmy Herring had joined Panic. I saw them in one of his early shows, and he had a songbook of handwritten roadmaps. I was like, “Ahh, that’s how you do it.” So I made a Black Crowes book—a rock-and-roll roadmap. It wasn’t a proper session player chord chart, it was just enough to keep myself from messing up. I didn’t trust my memory, so it could jog my memory in the heat of the moment. I would spend the mornings making charts of Dead material, and then Phil would teach us so many different little intricate strategies or nuances of music.

To what extent were you initially comfortable with the Grateful Dead songbook beyond the soul and blues covers?

Literally for five years with the Black Crowes, I heard the live recordings nonstop. I never went in on my own because I was on so many other musical journeys. But what was so fascinating was that studying roots guitar, the vocabulary of American guitar, and then studying Garcia, I was like, “Oh, there’s Chuck Berry. There’s Django Reinhardt. There’s Charlie Christian. There’s Doc Watson. There’s Mississippi John Hurt.” I recognized so many of Garcia’s influences I had studied myself. So even though I hadn’t studied his playing, I had studied all of the people that he looked up to, and that made me feel better. I’d rather have a like-minded foundation than learn the tablature note for note.

You eventually organized some Dead Blues shows with Phil. How did those come about?

Working at Terrapin I realized how many folk songs and blues songs they did. Grahame and I would curate these Dead blues songs and it felt so cool to cooperate.

Then we did those shows as a device to bring in musicians from further outside of Phil’s orbit. We did a show with the Blind Boys of Alabama, we did a show with Charlie Musselwhite and then younger friends like Devon Allman, G. Love and J.D. Simo. It was a great opportunity to bring in someone like Junior Mack, who I love from the Allman Brothers community and widen the gene pool. Grahame and I did one show in New Orleans that Phil wasn’t on, but usually he would be there and it was fun. Introducing Phil to the Blind Boys of Alabama or Charlie Musselwhite was really a gas.

I’m surprised he hadn’t met Charlie Musselwhite by that point.

It’s crazy because they were in all the same places at the same time, so to hear them catch up was really, really fun.

Phil played his ass off when we backed up the Blind Boys. They came to join us and he played their material. The funny thing was that night when they showed up, I was like, “Phil, I think these gentlemen are older than you.” He was like, “It’s not possible.” Of course they were in their early 90s, so I told him, “I think they got you beat.”

At that time did you think you might do something of your own with the concept?

Nah. It was just a fun way to do shows.

Back to Phil for a moment. On a couple occasions I stood just outside the pre-show huddle, leaning in as best I could without being intrusive. Can you talk about the way he characterized his musical goals and expectations in a manner that could be abstract and metaphoric?

Sometimes that’s what you have to do becausetalking about music is like dancing about architecture.

I think the pre-show huddle itself—just being there and making abstract noises together, like Bobby McFerrin meets Ornette Coleman— was just a fantastic joining of the spirits before you go on.

Thinking back, what also comes to mind is something sweet he said to me at Terrapin. When I would take the Pigpen role there were these blue-eyed soul, blues or Stax covers that I’d do in a psychedelic Memphis soul style. To do it, you’ve got to be bold. If you do a Pigpen rap, you’ve got to talk some silly bullshit. You’ve got to go all-in, and part of that concept is to recognize a medley or a tease. So I was kind of bold in that I would interject another song that wasn’t even on the setlist if the music led me that direction. I remember one night I was singing “Love Light” and then I went into Sly Stone’s “I Want to Take you Higher” and different things like that.

I was just bold about it because you have to be bold if you’re going to do that gig. Then after a set one night—although I think he might have been talking more about musical improvisation—he came up to me and said, “You have the proper type of mind.” I was like, “Oh, man, that’s fantastic. Thank you.”

That is quite a compliment coming from Phil.

It made my life. I’ll put that on my urn.

If you liked riding down the dusty trails of psychedelic rock-and-roll, he could get you there faster than anyone I’ve ever played with—just that feeling of wild, loud, electric, improvisational music. He cleared the path. If you followed his lead you’d get right to that feeling, which I love, I crave more than anything. That’s what I live for.

One thing about reinterpreting roots music that applies to this record, as well as North Mississippi and the Dead, is that the lyrics and the melodies are to be protected. What gets outdated are the rhythms. So I like making it danceable, camouflaging an ancient lyric in a more modern, palatable rhythm.

You’ve said that you recorded the songs on Dead Blues Vol. 1 as instrumentals and then set them aside. What had originally prompted you?

Oh, it was just fun. During quarantine, my friends and I made an instrumental record called MEM_MODS and this is an extension of that record.

I was learning home recording for myself. I always used the recording studio and the collaborative process of producers and engineers, but 2020 changed my life. I finally had to buckle down and learn how to do it. I always had tape machines and I hated recording on computers. I resisted it and I finally learned it.

I like to work on a lot of different things all at once. I just let things simmer on the back burner for years until the time or the inspiration comes to finish them.

What happened was when I turned 50, it was my resolution to finish all my back burner projects, with this being one of them.

Did you succeed?

Oh yeah, I did. Yeah. There are two long lifelong projects that I’m still working on, but every hard drive has been emptied at this point.

It’s a long list, with my children’s album (Magic Music for Family Folk), the Dead Blues album, the jazz record with Medeski and Vidacovich (Mississippi Murals), and an ambient drone record called Gravel Springs. So it was four projects and finishing is the hardest part. Man, it took a while.

After you’d finished, did you find that liberating, intimidating or a bit of both?

Both. It’s fun because I am writing tons of music that I don’t know where it’s going to go.

I’m working on some projects, including the two I mentioned that are bigger and beyond my skill set. So as a self-confessed control freak, it’s fun and intimidating and scary to work with bigger teams that know how to do things I don’t know how to do.

With Dead Blues, what let you to return to those songs with Datrian?

The instrumental record was on the shelf for months, nearly a year. Again, it’s trust the process, and one day I just woke up and I was like, “Oh my God, Datrian could sing Dead blues lyrics over this record.” I wrote that down, thought about it for a little bit, called him up and it just worked like a charm.

He’s so emotive and expressive. How would you characterize what he brings to bear?

It’s beautiful. He’s so humble and soft spoken and carries himself so unassumingly. I’ve never seen anyone shake an audience the way he can because the audience will just gasp. They’ll just be like, “What just happened? What did you just do?” But he is not showing off. It’s just beautiful talent, and a sad story. He lost his brother and came up hard. He came up in the church for gospel music, but also as a hip hop kid. He’s just a beautiful minister of music.

How familiar was he with these tunes?

Luckily he did not know the original material, which really helped him to interpret it. I would come up with the lyrics and I had a rough sketch of “I think these lyrics can go with this music.” I’d kind of sketch it out to get the vibe of it. In a couple of places I would reference the original melody but I’d really just let him have at it for the most part and then I’d reshape the music around it.

Was there a particular song you recorded where you felt like you’d either attained or exceeded whatever you’d had in mind for this project?

Yeah, it was probably the first two on the album, “One Kind Favor” and “Who Do You Love.”

The whole record was inspired by this idea that I wanted to make a record where I didn’t play guitar. I wanted to write the record on bass and keyboard, and for the most part, my friends are playing guitars on there. So I would write basslines and build little tracks with drum machines and then send them to my friend Paul [Taylor], who goes by New Memphis Colorways. He played on the majority of the record. Once I got the drums, I would keep expanding on it, adding keyboards and just following the music.

When “One Kind Favor” came together, which has horns and is the biggest, most produced track, the vocals were so breathtaking. I just couldn’t believe it was happening. I was like, “Oh my God!”

Then when we put the “Who Do You Love” hook on top of that synth melody of the song, it was a real cool moment. I didn’t know how we were going to handle that but it happened so naturally and easily.

I finally did play guitar at the very end. The fun thing was to go back and reference the actual vocal melodies in some of the guitar parts. I thought it would be fun to play the “Little Red Rooster” melody on the guitar as opposed to having him sing it.

What have taken you taken away from the process as whole that you might apply to future projects?

Well, I really have to say that building a super interesting instrumental band track is a powerful device. I’ve always started with the song and worked backwards and never wanted to put too much baggage on a song. I don’t want to overdecorate the tree, but this proves that if you have a really interesting band track, it’s only going to make the vocal even more interesting.

Since you’ve mentioned turning 50, you grew up surrounded by a number of older, accomplished musicians. Now that you’ve been at it yourself for some time now, do you feel a certain responsibility or impulse to share some of what you’ve learned with emerging players?

Totally. My dad used to say, “If you’re lucky enough to learn something, it’s your responsibility to teach it to at least 10 people.” I’ve always taken that to heart. R.L. Burnside taught me by hand. Otha Turner taught me by hand. My dad and his friends taught me by hand. Phil taught me by hand. So many great teachers, and when a musician teaches you their repertoire later in their life, I feel like they’re investing in the extension of their legacy.

Especially when it comes to folk music like Burnside or Otha or my dad—Phil had nothing to worry about—it’s your responsibility to keep those songs resonating, to keep ’em heard. It’s also your responsibility to find younger musicians and pass on what you know.

That’s been so fascinating, and what’s beautiful for me is that the young musicians, I’m learning from them. These guys are monsters. Talk about the evolution of the human mind and skill set. The younger musicians are unbelievable, not only in the evolution of technical prowess, but just how deep, how emotional, how much feeling they evoke.

When it comes to reaching out to the younger generation, thank God Butch Trucks reached out to us and we started the Roots Rock Revival Band camp because that has been the outlet. As a touring musician, it’s hard. It’s not like I have a community of musicians that I give lessons to at home. I’m never home.

The Roots Rock Revival camp—Oteil inherited it and we help him, but it’s his vision—is just a fantastic community of musicians, young and old, and a great place for us all to learn from each other. So I really appreciate Butch doing that. He had this yearning to tell his side of the story and pass on what he had learned. That’s why he started the camp, and man, it was really a great intention that has paid off a hundredfold.

Butch was also a forward-thinker when it came to things like his Flying Frog record label or his Moogis streaming platform.

I’ll tell you what, that’s true musically as well. I grew up loving the Allman Brothers, but as a guitar player, playing with Butch you just fall into these rhythms that you think, “This is how Duane or Dickey played.” His rhythmic vernacular was so strong that you just fell into these rhythms with him.

I often return to the concept of being confident but egoless, which he embraced and applied to his music.

The point is that you have to be confident enough to be there, and you have to be confident enough to maintain the state of mind—to be open enough to let the music come through. You have to get the ego out of the way because we are just vessels, if your intentions are such. I live for those moments when the music is playing itself.