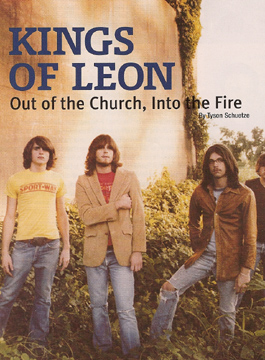

Kings of Leon: Out of the Church, Into the Fire (Relix Revisited)

Today as Kings of Leon announces some U.S. dates in support of its new album, Come Around Sundown, we present our June 2003 spotlight piece on the group.

The Saint in Asbury Park, New Jersey is one of those rock clubs that wears its eclectic history on its black-painted walls. The roughly 150-person-capacity venue is covered with bright-colored flyers, photos, posters and stickers from bands that have played the club since it opened in 1994. A lot of the bands are underground and obscure; flashes in time preserved more by their logos and graphics than by anybody’s memory of them. Behind the bar, standing in front of a black and white King of Leon press photo, Scott Stamper, co-owner of The Saint, discusses the time Cake played, Derek Trucks, moe., the several shows Ween played under aliases and other bands who stopped in before they broke out.

At the back of the club, facing the stage, the Kings of Leon are huddled together, nearly standing on top of one another, their beat-up boots only inches apart. They are watching the opening band. Sixteen year-old Jared who is the youngest member and bassist of Kings of Leon, is bobbing his head and moving to the music. The other three members seem less enthusiastic, but sway from time to time, occasionally moving closer, talking and then turning their heads to check out the few Jersey girls.

It is the first stop of a tour that lead singer and rhythm guitarist Caleb Followill says lasts “forever” and will crisscross the globe, exponentially increasing the number of shows the band has played in its brief existence. Kings of Leon do not look like a rock band on the cusp of a world tour and potential worldwide acclaim. Minus the shaggy hair and circa-seventies-Allman Brothers skin-tight clothes, they could be a group of Jersey teenagers who snuck into the bar.

Kings of Leon officially formed about a year ago. Principal members, Caleb Followill and brother Nathan Followill (drums), had been writing songs for about a year prior to the formation of the band and were signed immediately to a publishing deal. “Our publisher was proud of the stuff we were doing and wanted to see what some people out there thought. We just took some acoustic guitars and we went to New York and had some meetings with a few labels. We sat in their offices and played for them,” says Caleb. Recruiting fellow brother Jared and cousin Matt Followill (lead guitar), the band signed with RCA and was in the studio shortly thereafter recording its first five-song EP, Holy Roller Novocaine. “We had been a band for like one month before we did that. I had been playing bass for one month,” says Jared.

The Kings of Leon are aware that hype and explosive commercial success are not always good for a young band. “It is kind of scary if we sell a lot,” says Caleb, “because then it’s like, what are we?” Despite this admission they walk toward their future with the wide-eyed optimism that can only accompany a young band on the verge of something beyond their control.

Kings of Leon have not had much time to question who and what they are musically, but describing their sound, Caleb says, “To me it is rock and roll and blues and country. It’s just a combo of everything that we like.” Jared describes it a little differently: “It’s got a garage feel, a little bit of country, punk energy.” The garage comparison is probably the most accurate, as that was the only place the band had ever played prior to recording their EP. “Before we started playing gigs we would play in the garage and we would just bring as many people that could fit in the garage in there and we would have shows, just getting ready and getting prepared. And then we moved on,” says Caleb.

Twenty-five miles northeast of Nashville, the four members of Kings of Leon and their cousin live in a house with a soundproof rehearsal space that was purchased with an advance from RCA. Across from their house on Old Hickory Lake lives Johnny Cash. They describe the area as generally quiet, real country with tall grass, definitely laidback. It’s the very picture of domesticity compared to their nomadic childhood, following their father Leon, a traveling Pentecostal Evangelist, from revival to revival throughout the South.

“He was a different church every week, basically,” sys Nathan. Often accompanying their father on these excursions and playing the music at the revivals (which Nathan calls “gospel rock and roll shows” ) provided the best possible training for the Followills’ current life on the road as musicians. “We did 18 weeks one time, all five of us in the cab of an ‘88 Dodge Ram, three-and-a-half hours one way. We’d get out of school, get in the truck, drive to church, drive back that night, get home at two o’clock in the morning – from Tulsa, Oklahoma to Gravette, Arkansas,” says Nathan.

It was in the church that the Followills first fell in love with gospel music, which soon led to other music. “At first I guess coming out of the gospel influence, I really connected with oldies music. I used to sleep with a radio under my pillow,” says Caleb. But oldies music was a gateway to the blues to Chuck Berry to Tommy James and the Shandells to the Pixies, and to the time-honored southern tradition of walking away from the church, drawn by the secular sounds they found outside its doors.

“It is funny how in every one of our songs, people think that we’re doing something religious,” says Caleb, addressing the fact that religious themes do not exist in their current music. “Our songs are pretty much exactly the opposite. They’re about murder, transvestites and prostitutes,” says Jared.

“‘Holly Roller Novocaine’ was the only song that we’ve had any religious undertone in… and it’s not really religious,” says Caleb. The story of “Holy Roller Novocaine” documents a lascivious and horny Southern preacher and is taken directly from the Followills’ firsthand, behind-the-scenes experiences. “It’s calling someone out,” says Nathan.

“Straight outta 1966,” says Warren Haynes, describing the band. Haynes is leaning against the wall at the back of the Mercury Lounge in lower Manhattan two nights after the show at The Saint. The scene is considerably different; the air is thick with the smell of leather, attitude and reservation as Kings of Leon take the stage in front of over 200 music industry insiders for their first major showcase in the Untied States. Slowly people begin to warm to the band and by the end they have won over a good portion of the attendees, most skeptical of the considerable hype. The show, far from flawless but filled with raw enthusiasm and energy, is approximately the band’s twentieth public performance. “It was refreshing,” says Haynes.

In many people’s eyes, a group of young white relatives from the South who play rock music are either Lynyrd Skynyrd or the Allman Brothers. “It’s obvious that there’s only a few bands from the South that they can pick from and say, ‘alright, you’re this and you’re that,” says Caleb. A man who knows a thing or two about southern music places their music across the ocean. “They sound kind of British,” says Haynes. While the accents are clearly different, Kings of Leon fit the archetype of the young British-garage bands who invaded America in the mid-sixties and figured out how to play their instruments as they went along, not allowing their inexperience to stand in the way of their music.

The following day I meet the King of Leon in the lobby of their hotel. They are happy with the response to their show from the previous night. In between stories of the groupies in London, discussions of Warren Haynes’ presence, daydreams of returning to the church at the end of their career as a house band in Montana when they are bald and fat, there is one question that seems to loom larger than the others. Before I can finish the question I am cut off with a resounding “yes.” Do you ever feel all of this is happening too fast? “We’re all sitting here going ‘what the fuck,’” says Caleb. “We can look at each other and know that we’re not fuckin’ rock stars. We’re a bunch of assholes who are just lucky and getting to play music.”