Robbie Robertson: Seeing Around Corners

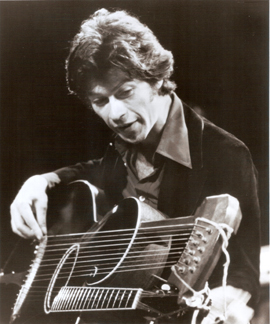

Photo by David Jordan Williams

Robbie Robertson carries the legacy of rock and roll with him, as someone who witnessed its birth almost first-hand and then put his heart and soul into shaping its future. With legends like this, there comes a time in their lives – one not necessarily easily recognized – when history needs to be accounted for. With How to Become Clairvoyant, his fifth solo album and first in ten years, Robertson’s time for reconciliation has come.

When Robertson walks into the lobby of The Village Recorder studios in west Los Angeles where he has a private office and studio, you can almost see molecules moving flowing past him in the air like a boat’s wake. The room is filled with a ping-pong table, but there is poshness to the place that. Everyone from The Rolling Stones to Bob Dylan to Pink Floyd have recorded here.

Dressed in black, Robertson has formidableness and exudes an earthy elegance like he’s both a man of the mountains and Manhattan. While he’s seen most of what rock and roll has to offer, he’s still searching for elusive moments and pieces to complete the experience.

Much of Robertson’s creativity follows a straight-line link to his earliest inspirations. It’s a sleight-of-hand where he is able to record such an autobiographical album as How to Become Clairvoyant and remain completely in the moment.

He has always found allies from a variety of sources, whether they were film noir classics or blues kingpins like Sonny Boy Williamson. The way that Robertson melds it all together is unique to him. When asked how he does it, he points to a lifetime of experiences.

“I happened to find myself in some amazing places,” he explains. "When we met up with Sonny Boy in Helena, Ark., he may have been near the end but he was also very aware of holding his own and defining that he played the blues. Very prideful, too. ‘I do not play no rock and roll,’ he’d say. That always stayed with me.

“I used that in the first song on the new record, but I got the title [ “Straight Down the Line” ] from the movie Double Indemnity, where Fred McMurray tells Barbara Stanwyck when they’re planning to kill her husband: ‘Yeah baby, don’t worry. We’re gonna do it straight down the line.’ Those kinds of lines never leave you."

When it came to writing music for The Band, Robertson called on experiences like the one with Williamson to deliver material that seemed like it was from the American South, so it’s hard to imagine Robertson being Canadian.

If listeners are still enthralled by what The Band created, then most don’t know the first-hand events that it sprang from. Today, Robertson lights up while remembering how it happened.

“It was an overwhelming experience, going from Canada to the Mississippi Delta when I was 16 years old to play with Ronnie Hawkins,” he says of his formative time with The Hawks prior to The Band. “This was where rock and roll grew up out of the ground, in that little area where Arkansas, Tennessee and Mississippi all meet. In that 100-mile radius, 75 percent of the music that I liked came right out of there.”

The Hawks, mostly young Canadians – along with Arkansas-born Levon Helm – got a glimpse into a world that was starting to vanish. Elder bluesmen, shake dancers and mountaineers were part of a surreal amalgam of characters. “Going there when I was young had such a powerful effect on me,” Robertson says. “It came out years later in my songwriting because all of those things were stored away in a kind of attic in my mind. When it came time to really sit down and write songs – to go into that attic and see what you could call on – it was like an American mythology of music.”

Today, he laughs at how The Hawks were fired from the Peppermint Lounge in New York City early in their career and learned a lesson that stayed with him forever. “They wanted us to play twist music, but we thought that was really corny and said no,” Robertson recalls. “We were coming from a different place. We’d been out there hearing music from up and down the Mississippi River and capturing that. When Music from Big Pink first came out [in 1968], people said you could hear gospel influences, mountain music, blues – all these things we’d gathered with a certain kind of maturity. We incorporated that into what we played without ever being too obvious. There wasn’t music like it then, but we felt like it was our music and stayed with it.”

Longtime fans will find an incredible depth in how Robertson looks back at the unraveling of The Band on How to Become Clairvoyant. For the first time – really – he clearly faces that historical juncture, singing: “Walking out on the boys was never the plan/ We drifted off course, couldn’t strike up the band.”

It’s a literal look at where that group lost its way. After The Last Waltz concert in 1976 at Bill Graham’s Winterland arena in San Francisco, the five members were at a crossroads. For Robertson, continuing on as a group without drastic changes to their lifestyle was not an option. “I just knew I couldn’t work in the circumstances we were in,” he says. "We needed to turn things around or put them upside down from how we’d been working. Everything had become so unhealthy and dark, but I didn’t know what to do. But I never said I was quitting The Band.

“What I was saying was we can’t go out on the road in the condition that The Band was in. We can’t do that. So the idea was to go off and shuffle the deck, do some solo projects and freshen up. Then come back together. But nobody came back. Everyone was relieved to be off on their own. I just saw the writing on the wall and acknowledged it.”

For fans, that might have made Robbie Robertson the bad guy; but for him, it was a matter of staying true to what he thought the group’s legacy was.

How to Become Clairvoyant is Robertson’s fifth solo album and his first in more than a decade. It feels like the one he’s been meaning to make since he left The Band all those years ago. There is a breathless self-awareness at the heart of each song that pulls his five decades of music making together into a cohesive whole. For those who still think that The Band was the apex of a certain school of rock and roll, this new music will arrive like an alluring postcard from a longtime friend who’s been out of sight but not out of mind.

The songs tell a life story even though that wasn’t the initial plan. “It evolved into that,” Robertson says, “and very naturally. That’s why I was able to go and write in such a reflective tone. I’ve never been very comfortable doing that in the past, which is why I wrote as more of a storyteller using fictional characters. Of course, a lot of your personal life seeps into that. Still, I was always adverse to the ‘me, me, me’ songwriting syndrome. It was a self-indulgence thing I was never comfortable with. And when I started writing for The Band, I was writing for others. I couldn’t show up and say, ‘Guys, I just wrote another song about myself.’ That wouldn’t have worked.”

For an artist like Robbie Robertson, there comes a point when he must decide whether it’s worth trying to make new and relevant music. After a ten-year gap of solo albums, the dilemma seemed quite real for him. “Without sounding presumptuous about this, I thought quite a few years ago, I thought, ‘I’ve done what I’ve done,’” Robertson says. “I decided I’m going to do what I like and not going to do what I don’t like. I’ve earned that. For me, though, I have a real yearning for learning things and challenging myself. I like to do things that I don’t quite know how to do, and making discoveries. So that’s how I set out to make this album.”

Robertson’s basic building blocks of a band for How to Become Clairvoyant consisted of bassist Pino Palladino and drummer Ian Thomas. With those two on board, he traveled to London – to “someone else’s ‘hood” – to work with longtime friends Steve Winwood and Eric Clapton and flesh out the album’s sound.

The sessions quickly took on the immediacy of a working group. There is the push and pull of what humans come up with in a recording studio that remains the essence of rock and roll; it cannot be made to order or duplicated. It’s the magic that lets players conjure life from the air and put it on records for infinity. Those that chase those spirits know the ground that they’re walking on. And that includes Robertson.

“Winwood and Clapton are guys I’ve known for years, but we’ve never done anything like this before,” he says. “It was my job to figure out how to make something really special happen in this situation. They’re always good at what they do, but to make it take on that other feeling without showing off – that’s what we went after. When Eric and I are playing together, nobody is trying to do acrobatics. This is like talking guitars having a conversation. It’s not about seeing who could yell the loudest. We’re past that.”

Robertson’s background in The Band is proof that he believes in musical fellowship and knows that artists collide when things come alive onstage or in the studio. On new songs like “When the Night Was Young” and “This Is Where I Get Off,” those collisions are career highlights for the musician.

“Something deeper happened,” he recalls of finding the sessions’ stride in those songs. “We quickly found out that place that’s above and beyond, where you know you’re in the zone, which made me so happy. We hit a certain kind of grace – something that’s the real thing. It’s interesting because sometimes you don’t know what you’ve got when it’s happening. You just want to live in that place the best you can.”

After the band had recorded in London for three weeks, the album took a fortuitous left turn. Robertson returned to the U.S. to work on the soundtrack of Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island film. As he began searching for the right modern classical music for the movie, the process began to influence How to Become Clairvoyant.

“It was an interesting experiment and it let me hear how some outside touches on the London sessions might open things up,” Robertson says of the soundtrack project. “So when I came back to finish my album, I saw it in a different light. I could see how opening up the casting could really help the music become something even more. Working with [singer] Trent Reznor, [guitarist] Tom Morello and [pedal steel guitarist] Robert Randolph gave me a clearer vision of the possibilities and allowed me to go down a new path. In the end, it allowed me to be even more reflective in the songs. I got lucky.”

One of the best examples of this luck is “He Don’t Live Here No More,” a song that still gives Robertson a bit of the shakes. He looks at the end of the ‘70s, a time excess in the entertainment world – and for him.

“It was something that had developed in the culture of music where I didn’t know anybody that didn’t have that excessive lifestyle,” he says. "There was a certain kind of decadence then and a lot of cocaine everywhere. Some people dabbled and some crashed and burned. Some hit a wall and learned you can’t do that or you’re going to die. Everybody I knew was indulging.

“Instead of driving fast cars like in the ‘50s, there was a different kind of recklessness. In the ‘60s, it was more of a ‘do something good, be free, change the world and stop the war’ mood. The ‘70s was a different game completely. So this was a hard song to share. Looking back, I saw my own experiences with Martin Scorsese. He and I went through the bubble together and it burst. Thank God. I lost a couple of brothers in The Band to drugs and alcohol, so I saw it first-hand.”

How to Become Clairvoyant is something of a primer of Robbie Robertson’s life so far. When told how he’s always enveloped himself with a certain sense of mystery – noting those photographs of his hooded eyes in the early Band images – he laughs quickly and shakes his head. A bit of acceptance is behind that laugh, though, and he knows it.

When pressed about the notion of clairvoyance and how that talent comes in handy during such a long history in music, he admits that it’s something he’s always respected. “Sure, I yearn to see around corners,” he admits, “and to the best of my talent, I sure try every way I can. I’ve been very fortunate to have worked with a lot of the best musicians over a very long period – some you’ve heard of but also many you haven’t. It’s helped me see what’s important and taught me a lot. As for seeing the future, I don’t claim to have it down but I am in search.”

In his office at Village Recorder, the various guitars hanging on the four walls give silent testament to Robertson’s legacy as they seem to almost smile on their owner – simply glad to be part of his continuing journey. One in particular, an older blonde Fender, catches the eye. When asked if it’s the instrument that Robertson played on John Hammond’s So Many Roads album in 1965 (before he’d made his name helping Dylan storm the walls of rock and roll), he says no, but that it was a similar one. Forty-six years later, it’s just another entry on a long laundry list of credits.

Ever gracious, Robertson gives thanks for the memory and heads back into the studio. He has more songs, more sessions and more phone calls to make. The sparkle in his eyes says that he wouldn’t have it any other way.