Relix 44: The Weavers’ ‘Wasn’t That a Time!’

Welcome to the Relix 44. To commemorate the past 44 years of our existence, we’ve created a list of people, places and things that inspire us today, appearing in our September 2018 issue and rolling out on Relix.com throughout this fall. See all the articles posted so far here.

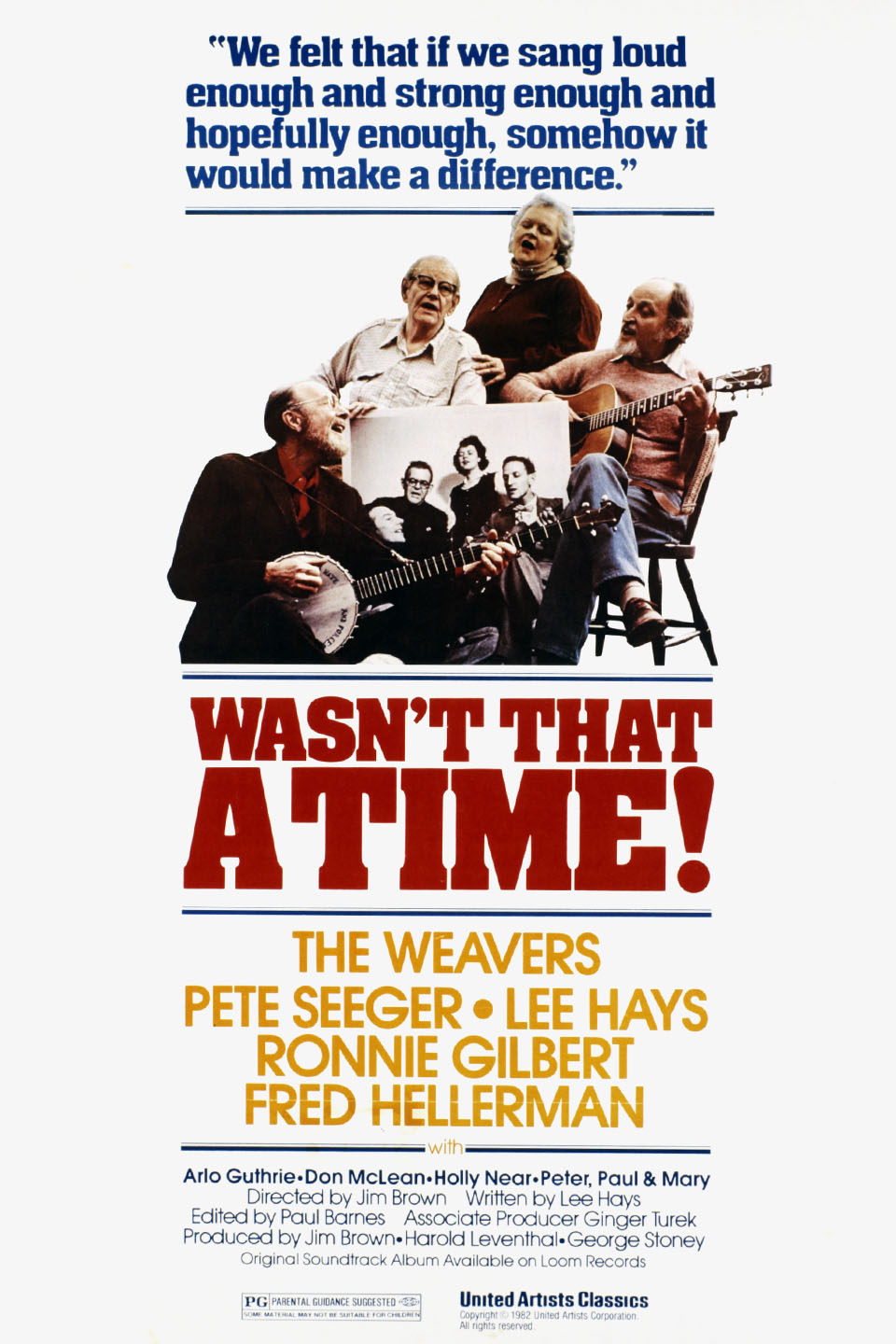

Still of the Moment: The Weavers – Wasn’t That a Time!

My earliest moviegoing memory—surely reinforced by my mother’s telling, but still lodged in me—is the weird shame of an usher not wanting to admit me to see Jim Brown’s Wasn’t That a Time!, the 1981 documentary about the reunion of folk quartet The Weavers. We’d driven into the City from Long Island for it. They were unquestionably my favorite band—my first favorite band. I was taken by the energy of their voices, the mysterious old folk melodies, and Pete Seeger’s friendly spirit. My mother informed the usher in no uncertain terms that I wasn’t too young, and would be perfectly behaved, which I was, watching attentively and singing along, exactly as the band intended.

A genuine top-10 pop act in the early 1950s, the band’s string of hits turned folk songs into global standards, including Lead Belly’s “Goodnight Irene,” “The Wreck of John B”—what the Beach Boys retitled “Sloop John B”—the South African “Wimoweh”—with nary a line about a sleeping lion when the Weavers did it and more. They wrote “If I Had a Hammer,” considered too controversial to sing onstage until the ‘60s. Grown from the activist organization People’s Songs, The Weavers’ repertoire evolved from deeply set beliefs about class equality, social justice, and world peace—beliefs closely associated with the entwined American socialist movements in the years before World War II. Entering the hit parade at the same time that Joseph McCarthy and others began to fabricate associations between the American Communist Party and Soviet espionage, The Weavers found themselves near the center of the Red Scare, blacklisted out of a career.

Reuniting a few years later, the band swapped hit singles for best-selling live LPs, influencing musicians like Jerry Garcia, David Crosby and Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kantner, before breaking up in 1963. Jim Brown’s film captures the band a decade-and-a-half-later, reuniting (again) around Lee Hays, the band’s bass singer and chief theoretician. An alcoholic in failing health, he was nearing the end of his life, both of his legs amputated following untreated diabetes. Filled with the same quietly absurd Southern humor as during The Weavers’ peak, the Arkansas-born Hays was sometimes erroneously referred to as a former minister, and in Brown’s film, it’s easy to see and hear why.

Needing a blast of radical politics in the form of hopeful harmonies, I watched the film for the first time in years a week or two after the 2016 presidential election, and I certainly got that. But, as Marty DiBergi said, “I got more, a lot more.” Watching the band find closure for Hays, it’s also possible to sense—however fleetingly—the wounds they’d collectively endured, and the intentionality with which they’d done their cultural battle.

My book about the Weavers, Wasn’t That a Time: The Weavers, the Blacklist, and the Battle for the Soul of America—their first biography—comes out in November (on Election Day), named for the same Weavers song as Brown’s film, a song that earned all four members subpoenas from the House Un-American Activities Committee. More than anything, though, it was Lee Hays who sent me spiraling into the band’s history, speaking exactly the words I needed to hear when I watched the film decades later.

“This too shall pass,” he told the Carnegie Hall audience, only a few weeks after the 1980 presidential election. “I’ve had kidney stones and I should know.”

This article originally appears in the September 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.