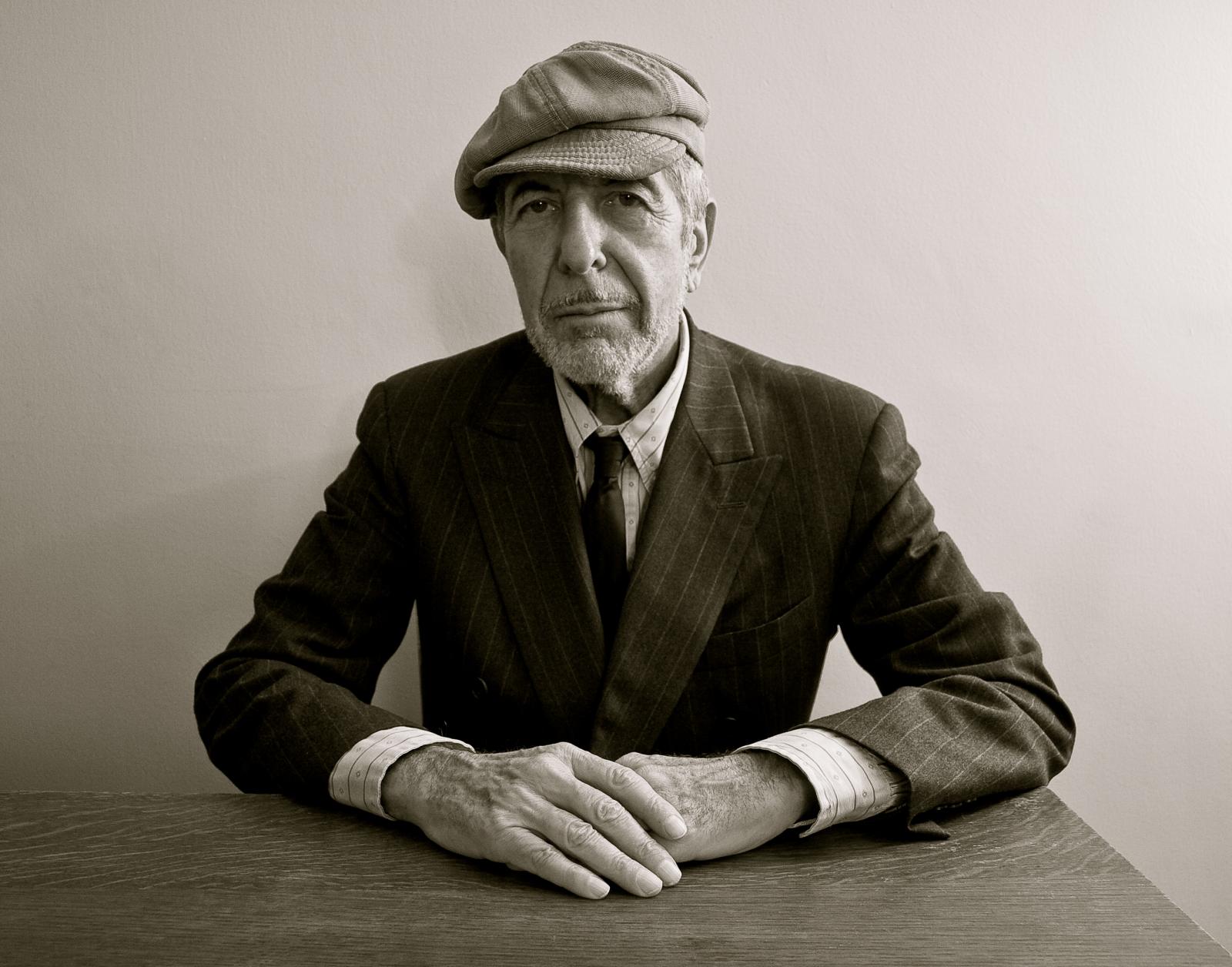

Leonard Cohen: The Mourner’s Kaddish

Leonard Cohen turns in another landmark album from beyond the grave, thanks to his son Adam and an all-star indie-rock cast.

There’s an interview available on YouTube of a young Leonard Cohen, conducted by the Canadian Broadcast Corporation in 1966. At the time, Cohen was still a budding songwriter—poetry was his main gig—and the interviewer grills him in a way you rarely see artists grilled these days. She’s tough and challenges him on his philosophies about art and poetry, and what it all means in the grand scheme of things. But Cohen doesn’t waiver; he remains steadfast throughout the process and, at times, seems to relish in his defenses. They come to him quickly as if there isn’t a choice. Poetry will stand up against anything—any skepticism—but doesn’t need to be defended at all.

“Everything keeps going or it stops,” he told the interviewer. “You know when you’re happy. There’s been so much talk about the mechanics of happiness—psychiatry and pills and positive thinking and ideology. I really think the mechanism is there. You just have to get quiet.”

Quiet is an apt word to describe the last several years of Cohen’s life. Well into his 70s and early 80s, he released several albums that placed him back into the pop-music spotlight, beginning with 2012’s Old Ideas, and continuing with 2014’s Popular Problems and 2016’s You Want It Darker. The work was strong and Cohen’s distinct baritone and wry wit flourished throughout. But the music was sparse, which gave his voice an extra weight behind it.

When Cohen passed away in November 2016, just weeks after You Want It Darker was released, he was 82 and, by all accounts, exhausted. He had Leukemia and was dealing with compression fractures of the spine. One Darker song even included a line from the “Mourner’s Kaddish,” a Jewish prayer traditionally recited in memory of the dead.

But he kept on recording until shortly before his death, choosing to work with his son Adam, who is a musician and producer in his own right. Cohen would often have to sit down during those final sessions—but the work that was released on Darker wasn’t actually the last music he recorded. He left behind a handful of unfinished ideas and vocal takes, a parting gift that Adam has now turned into a new, original posthumous album. Thanks for the Dance picks up where Darker left off, boasting nine numbers that aren’t necessarily a last statement as much as they are one more glimpse into the mind of a master poet and musician. Everything keeps going until it stops.

To assemble the music behind the vocals, Adam tapped longtime Cohen guitarist Javier Mas, Death Cab for Cutie keyboardist Zac Rae, and engineer and multi-instrumentalist Michael Chaves, who’s worked with a wide range of artists over the last two decades, including John Mayer and Sarah McLachlan. “When we began under Adam’s direction, we all knew what to play because we were guided by Leonard’s voice,” Chaves says of the Thanks for the Dance sessions.

“The foundation of each song came quite naturally and quickly. “This album is an extension of You Want It Darker,” he continues. “We began work on most of these songs with him in his final days. Some he sang to a simple keyboard and bass drum beat, and some of them were readings that he had not yet set to music but recorded because he felt that we would need more songs for another record. Leonard said to Adam and myself: ‘You guys finish these; you know what I like!’ So we’ve been working on this collection of songs, off and on, over the past two years.”

***

Understanding what Cohen wanted was critical to making Thanks for the Dance. Posthumous albums are a common occurrence in today’s musical landscape. From a business and fan perspective, it makes sense to make every last bit of an artist’s work available. But rarely do they sound so complete—something that the artist would have released if he or she was still with us.

To that end, Adam expanded his father’s musical palette in subtle ways for this last hurrah. He brought in famed producer and musician Daniel Lanois (U2, Bob Dylan, Neil Young) to add some piano and guitar effects and to help out on backing vocals. “My ears were fresh, my input was fast, and my advice to Adam was clear and pure,” Lanois wrote on his website of the experience. “I sang, I dubbed, I spun, I played the piano, played the bass and waved my arms to keep any dust from collecting on me. I left my dust at home because I knew Adam would have his own dust to deal with. It’s just the way it goes with record-making—the process eats away at innocence.”

Lanois wasn’t the only other guest to drop in on the sessions—in fact, Adam assembled a host of indie-rock luminaries to help flesh out the songs. Beck played the guitar and Jew’s harp on one standout number, “The Night of Santiago”—a song that finds Cohen reminiscing about an intense love affair. Jennifer Warnes, who collaborated with Cohen in the ‘70s and ‘80s, lent her vocals to the title track. The tracks also made a pitstop in Berlin. In August 2018, numerous musicians descended on the city for the PEOPLE Festival, an arts event curated by Justin Vernon and The National’s Bryce and Aaron Dessner. While there, Adam had a handful of musicians come by to offer their input and lend their talents: Feist and Damien Rice provided some vocals, Bryce played guitar and Arcade Fire’s Richard Reed Parry added some bass to “Santiago.”

“I didn’t know about it until about a half an hour before it was happening,” Parry recalls of the spontaneous session he found himself involved in, after being introduced to Adam by a mutual friend, Montreal producer and former Arcade Fire drummer Howard Bilerman.

“You enter the chamber and your jaw drops a little bit when you realize you’re hearing these songs from beyond the grave,” Parry says. “[The songs were] lyrically and vocally as strong as anything he ever did. Adam was quite relaxed while people were coming into the studio to hear this stuff. Obviously, we were all musicians and had a certain sensitivity. He was playing this secret record that he was assembling. It opened the floor up to me—I was there only for so long. He was like, ‘What do you hear?’ ‘What do you feel?’ ‘What are you struck by?’ He genuinely wanted to hear my response and if I had any ideas.”

“As for the instrumentation on this new record, we wanted it to be a journey through the Leonard Cohen catalog—from his classical nylon string guitar to the female background vocals and lush pianos and strings he often utilized,” Chaves says. “We wanted it to feel like traditional Leonard Cohen, and still honor his love for exploring new sounds as well.”

For Canadian musician Patrick Watson, who co-produced the song “The Hills” and played synthesizer and organ, the challenges were two-fold. “One thing is: You’re working with a legend. And when you’re working with a legend, there comes a responsibility to do a great job and do it justice. And also you’re dealing with a master lyricist. To put music behind a master lyricist is quite an amazing thing. It’s a privilege, if anything. It was a very special thing to do.”

***

Leonard Cohen rarely gave interviews toward the end of his life. But one comment he made in 2016 speaks volumes about where he was during his last years.

“You’re dying, but you don’t have to cooperate so enthusiastically with the process,” he told The New Yorker. “I no longer have that voice that says, ‘You’re fucking up.’ That’s a tremendous blessing.”

“My memories of those days are quite joyous,” Chaves recalls of the time he spent with Cohen during the Darker sessions. “Despite the fact that he was in a lot of pain, he managed to get the work done while having some fun at the same time. I miss sharing cigarettes with him on the balcony, having him pour me a tequila or watching him get up out of his chair to dance to something he liked.”

These outlooks—the balance between pain and joy, the end of a life and the beginning of something new—shine through on Thanks for the Dance in remarkable ways. Cohen’s voice is extremely low and, at times, quite hushed. But the intonation feels deliberate and Cohen speaks and sings with clarity.

On “Moving On,” over a gorgeous acoustic guitar, he questions, “Who’s moving on?/ Who’s kidding who?/ I loved your face, I loved your hair/ Your T-shirts and your evening wear.” The song is a sequel of sorts to his classic “So Long, Marianne”—a tribute Cohen wrote for his former muse Marianne Ihlen after she passed away in July 2016. The album’s opener “Happens to the Heart” positions Cohen’s voice among lush guitars, where he declares, “I was working steady, but I never called it art/ I got my shit together, meeting Christ and reading Marx/ I’ve come here to revisit/ What happens to the heart.”

“It was extremely moving, hearing such a naked track,” recalls Avi Avital, who plays the mandolin on “Moving On.” “You can only imagine discovering a new song. I immediately closed my eyes and knew what I wanted to bring in terms of the mandolin. It’s clear that a lot of soul was put into this album. Everything is meaningful.”

The album’s final track, “Listen to the Hummingbird,” came to life in an even more unusual way. Cohen gave fans a preview of the song at an event for Darker in October 2016, when he recited the lyrics to “Hummingbird” live. A recording of that moment was used as the vocal track, with the background noise removed.

Those types of moments will no doubt one day be ingrained in listeners’ minds as much as, say, Cohen’s most famous song, “Hallelujah” or one of his recent concerts. After stepping away from the live-music world for a while, Cohen returned to the road near the end of his life and eventually found himself playing arenas worldwide. His final show took place on Dec. 21, 2013 in Auckland, New Zealand. In more ways than one, he went out dancing—the last song he performed was even The Drifters’ classic “Save the Last Dance for Me.”

Cohen died in his sleep on Nov. 7, 2016 after a fall during the night. He was buried in his hometown of Montreal, laid to rest next to his mother and father. About seven months later, Adam picked up where he and his father left off.

“It’s about the writing at the end of the day,” Parry says. “Underneath the songs, it’s the lyrical aspect—it’s remarkable. The music is just there to create a frame around the words.”

“Obviously Leonard isn’t around, but you’re hearing all these different ways he touched people,” Watson says. “And that’s going to come with the sounds that were chosen. That is equally as beautiful. You have access to the way people heard him—even though, in their brains, they were probably like, ‘What would he do?’ But that’s an impossible question to ask.”

This article originally appeared in the Jan/Feb 2020 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more subscribe below.