Jim Marshall’s Visual Story of the Grateful Dead

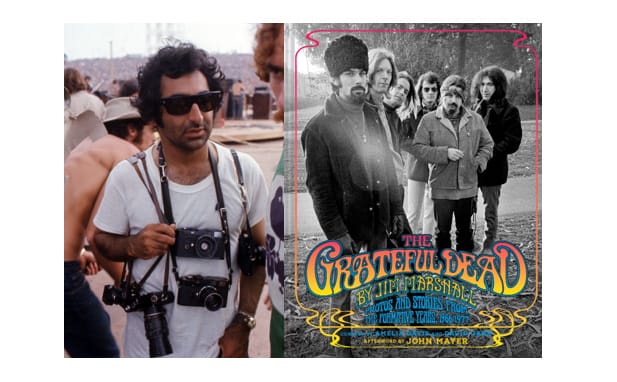

Jim Marshall was one of the most renowned photographers of late 20th century American culture, with a particular affinity for jazz and rock music. He produced iconic images of Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Miles Davis, John Coltrane and many others, as well as more than 500 album covers.

Marshall also took thousands of Grateful Dead photos, over 200 of which have been collected in a new book of images and essays. Amelia Davis, Marshall’s longtime assistant and the manager of his estate, co-created the work with journalist/musician David Gans. As she notes in her introduction to The Grateful Dead by Jim Marshall: Photos and Stories from the Formative Years, 1966–1977, they “combed through all these 52,704 images and through a dizzying whirlwind of history.” As the subtitle suggests, the images are contextualized and complemented via essays and captions from the band’s extended family.

Davis, who worked with Marshall over the last 13 years of his life—until he passed away in 2010, at age 74—observes, “Jim thought of himself as a reporter with a camera. So I approached this book thinking of the Grateful Dead as people— how they did things and how they influenced things. I learned about the Grateful Dead through Jim, hearing him talk about his experiences, and I can really hear their music in the photos. For me, that was a revelation— to be able to look at these photos and really feel what they were doing.

“Jim talked about how they were very improvisational and a lot like jazz. That’s why he was drawn to them—he loved that no show was going to be the same. A lot of it was in the moment, and you can’t replicate what you’re feeling at that moment. It also had to do with the vibe of what was happening around them. I think you can see that in these photos, even when they’re not playing, when they’re just sitting down and being goofy.”

“One of the things I’ve always loved about Jim’s photos is that I never feel like a voyeur looking in,” she adds. “I always feel like I’m a participant and that I’m there with them. I think that’s what this book does. Jim’s photos make you feel like you’re a participant experiencing everything that they’re experiencing at the same time.”

***

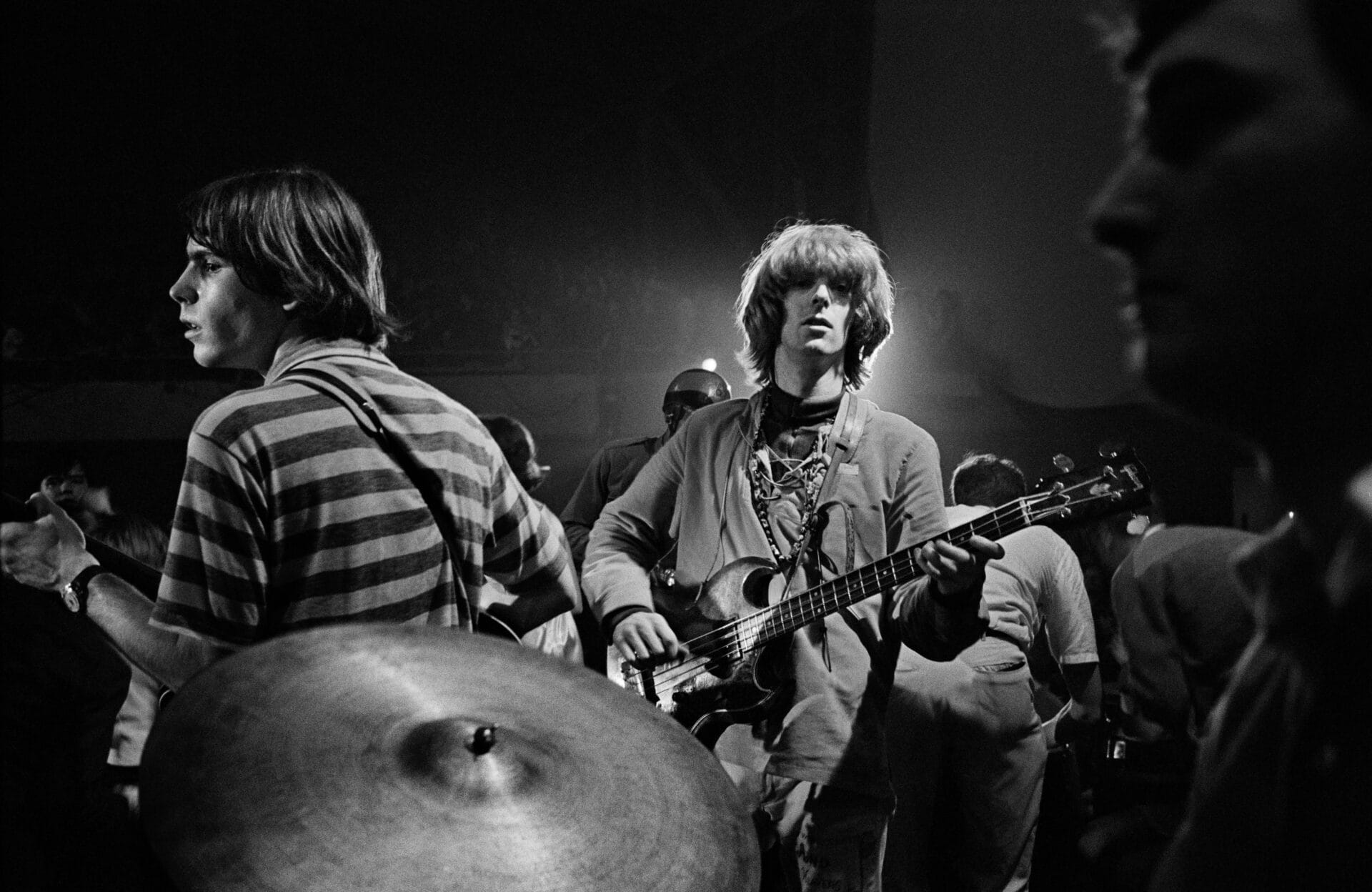

Ken Babbs and the Grateful Dead, Woodstock, Aug. 16, 1969

Some people might see this and not realize it’s Woodstock because Jim didn’t really show the photographs of the Grateful Dead from Woodstock. The ones that you typically see are of Jerry next to the “Dead End” sign. The guy in the background next to Bill Kreutzmann is Ken Babbs, who’s one of the Merry Pranksters and was tripping like crazy.

The band came on at night and had so many problems with the sound system. I think Bobby got electrocuted at one point because the wiring was so bad, and they said they didn’t enjoy the experience.

This has a different kind of vibe than you get from other Woodstock photos. When you see Jefferson Airplane, dawn was breaking and the light was coming in, but this is kind of dark. It feels dark too, like something’s not right.

Pigpen, 1967

In talking to people who knew him, you get the sense that Pigpen felt alone at times. He was kind of the bluesy guy, then as the Grateful Dead started to switch out of that, he began to feel left out. I get the sense in this photograph that he’s just by himself walking down the street. To me, that’s also how Jim felt a lot of times. He had an outsider kind of vibe and view of himself. It spoke to me that maybe not only is this Pigpen, but it’s also kind of a self-portrait of Jim feeling alone. That’s how I look at that photo.

Grateful Dead, Straight Theater, Sept. 29, 1967

The Grateful Dead advertised this as a dance class because the artists who had fixed up the theater had been denied a permit from the city. So this was a way to get around it. I love how it says, “Dance Class,” and then you’ve got the psychedelic projections, where they would stick oil on a slide to get weird movements and drips and stuff. Then, if you look in the corner on top of one of the speakers, there’s a God’s eye that they made out of string, which is so from that era. If you’re talking about it from a technical point of view, you’ve got the projection light, and you have the house lights on, but they’re dim. Jim still got the shot, though, which is amazing,

Grateful Dead, Santana and Jefferson Airplane, KQED-TV A Night at the Family Dog special, Family Dog on the Great Highway, Feb. 4, 1970

This was from an old ballroom that was at Playland on the beach. Chet Helms organized this event, and what’s really wonderful about this photo is you can see all these San Francisco bands coming together and jamming. It shows the camaraderie between the bands themselves and the respect they had for each other. It’s got that San Francisco vibe to it.

Grateful Dead, Artists Liberation Front Free Fair in the Panhandle, Oct. 16, 1966

Mountain Girl said this was a very important event for them. They advertised it and it was family-friendly—they had things for kids to do, like face painting. But the Grateful Dead didn’t expect so many people. They were spilling out into the streets and you can kind of feel that. You’ve also got these really goofy speakers and the stage was thrown together with two-by-fours. So it’s just not something you would see today. There’s also no police presence really to speak of. So people are right up at the front of the stage—again, that would never happen today because it would be gated off. So you have this feeling of a time when it was all so open and free, and everybody was there enjoying it.

Bob Weir and Phil Lesh, Trips Festival, Longshoremen’s Hall, Jan. 23, 1966

Jim often had to be improvisational, just like the band, when he was photographing them on stage. From a technical standpoint, this photo was incredibly hard to get. He was in this venue where there’s very little light, using available light with his completely manual camera and he got the shot. This was an Acid Test. Prior to this, those kinds of events were hush hush. You didn’t go to them unless you knew the secret of how to get there. This one was out in the open at Longshoremen’s Hall, and they advertised it. So anybody who was willing to put down $2 could get in.

***

Jim is often described as a photojournalist as much as a music photographer. Can you talk about his approach and development?

Jim was a self-taught photographer. In 1960, he bought his first Leica camera, which was an all manual camera, in which you’re not looking through the lens itself. You’re looking to the side of the lens through a viewfinder, which enables you to compose the photo. For people who are not used to that, it throws you off. It’s a serious camera that a lot of photojournalists, like [Henri] Cartier-Bresson, used. One of Jim’s heroes was Robert Capa, who was a war photographer.

So you see the subject and you capture it with your camera. It’s very mechanical and you have to have an eye for composition. But for Jim, it was about capturing the moment and feeling that moment through the photograph, which is something that can’t be taught.

Jim was 3 years old when his family moved to San Francisco. Then, by the early ‘60s, the jazz scene was really happening in North Beach, so that’s when Jim went into the jazz clubs and really taught himself about the manual camera and also about available light. In those jazz clubs, it’s smoky, it’s dark, people are moving, and he was able to teach himself the different film speeds and apertures to capture the moment in that kind of environment.

That’s where he became good friends with Miles Davis and John Coltrane. They really trusted him, and he took a lot of photographs of those jazz guys and also the counterculture. It was starting to happen with the poets of North Beach and at City Lights—you had Allen Ginsberg with Howl and all that going on.

Then Jim did stuff for record labels on the West Coast. A lot of it was jazz because there really wasn’t much rock-and-roll yet in the early ‘60s.

From there, he moved to New York from ‘62-‘64, to establish himself as a photographer on the East Coast. That’s where there were the big record labels like Atlantic and magazines like Life. That’s where he met Bob Dylan. There was a huge folk scene going on. It’s where he took the famous photo of Bob Dylan rolling the tire down the street with Suze Rotolo. So he did a lot of folk, he did more jazz and he also did a lot of civil rights stuff because in ‘63 and ‘64, the U.S. was still segregated.

Then he came back to San Francisco when Haight-Ashbury and the counterculture started booming, and everything kind of went on from there with the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane.

By the time he came back to San Francisco, he was a very well-known, established music photographer and photojournalist. So he befriended a lot of the bands. As a result of that, he always knew what was going on, like when they were going to do a pop-up in Golden Gate Park. So he was able to be there and he had that access.

There is an intimacy to many of photos, yet he often had multiple cameras hanging around his neck. How did he prevent his subjects from becoming self-conscious?

Even later in life, when he was not really photographing anymore, whenever we would go out, he would grab for his camera. It was just habit. He never wanted to miss a moment.

When he was younger, he had five different cameras. He had fixed lenses, so he knew which lens could get which kind of composition based on how far away the subject was. His cameras were an extension of him, and he knew exactly which one to use for the moment he was in.

People got used to Jim wearing all these cameras. It became one of those things—“Oh, it’s Jim.” So he was able to get these very intimate, unposed moments.

Part of the genius of Jim is he used available light, so he wasn’t carrying around backdrops and studio lights where he’d have to set things up. Whatever the light source was, whether it was inside or outside, he was able to capture it because he knew his cameras so well, and he knew that he could get that photo.

I also think he was able to have a connection with these musicians because he felt like an outsider. Jim called himself Assyrian, but he was Iranian. He wasn’t this blond, blue-eyed guy. He looked like a foreigner, and he fit right in with these other people who also felt like outsiders, including the whole counterculture movement.

His personal demeanor is often described as erratic. So when I read how meticulously he organized his work, I was somewhat surprised.

He was very abrasive. A lot of the times, he would say things to shock people, just to see how they’d react, and if somebody pushed back, he was like, “They’re OK.” He did drugs— he never hid the fact that he was a cocaine addict. He also carried around guns and knives, although one of the reasons is because he felt like an outsider, so he always thought he had to defend himself.

That was the persona and you’d think this guy would just be crazy. But he was also very strict and organized when it came to his photography because that’s how he made his money. He was a working, breathing, living photographer. If he was not organized and wasn’t able to find his images quickly, he wouldn’t get the job.

Jim was married twice, but he never had children, so his photos were his children. He protected those children—they were organized and taken care of.

Photography was Jim’s life, and that’s why he had two failed marriages. He couldn’t really be in a stable relationship because, for him, photography was 24/7. It was his first love and that came first—above everything in his life. So he respected and cared for his children.

How did you approach that treasure trove of more than 50,000 potential Grateful Dead images?

I was his assistant for the last 13 years of his life. So we talked a lot about his photographs and he’d tell me stories. I’d also file things, and when the gallery sold a photograph, we’d get the negative taken to the printer and have it printed. I knew his system because I had worked it.

Inheriting Jim’s millions of children was overwhelming, but I knew the organizational aspect of it, and I knew the stories behind them. In taking care of Jim’s archive, I’ve discovered so many gems that nobody has seen because Jim had so many photographs, but he would tend to print the ones that people wanted and he knew he could sell.

So on a roll of film, the proof sheet, maybe there’s the hero shot of Jimi Hendrix with his arm in the air at Monterey Pop. But on that same proof sheet, there might be six or seven other extraordinary images that Jim never printed. Going through his archive, I felt like an archeologist on this important dig, uncovering all of these things that nobody had seen before. Jim entrusted me with his legacy and part of my goal has been to show people these things that Jim wasn’t willing to show when he was alive.

Did you have an overriding theme that informed your selections for the book?

We wanted to make people feel like they were part of the family. So as you look at these photos and you read the stories, you’re welcomed in and invited to see how they lived. The goal is also to show people that the Grateful Dead were human beings, they weren’t these gods.

It was fun to work with David because he was like a kid in a candy store. He’d say, “Oh, my God, I’ve never seen that! I’ve seen tons of Grateful Dead photographs, but I haven’t seen these!” He was so enthusiastic, and it was such a fun book to put together because everybody’s heart was in the right place.

There’s never been a book of Jim’s Grateful Dead photos. He’s had his photos in different books and magazines but never just one book. So we felt it was about time. Like I said, Jim got stuck in his ways. Once he saw that a photo sold, he was like, “OK, I’m just going to stick with this one photo and print this over and over again.” With the Grateful Dead, a lot of it was that Jerry “Dead End” photo from Woodstock that people loved. That one is kind of cool when you think about it because it was not set up, it just happened. That’s Jim seeing the moment.

I don’t think people understand how much thought goes into a book. It’s not just throwing photographs together. A lot of it is picking the photographs that are visually interesting and powerful and tell a story as well. That’s what I think this book accomplishes. It’s a visual story of the Grateful Dead through Jim’s eyes.