How to Steal a _SMiLE_ : An Alternate History of The Beach Boys’ Lost Classic

As Brian Wilson turns 70 today, we look back to this feature on SMiLE from our December issue

There are those who maintain that the “Mona Lisa” on display in the Louvre in Paris is a fake, replaced by a forgery after its daring 1911 theft. The appearance of The Beach Boys’ SMiLE during this shopping season might raise similar eyebrows, but it will undoubtedly induce equally deep ear-to-ear expressions of happiness a few inches below.

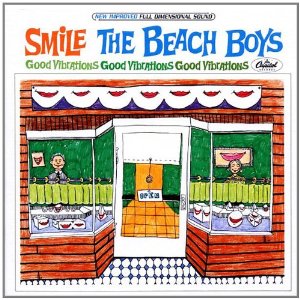

Indeed, the package (officially titled The SMiLE Sessions ) presents itself with the original jacket art designed by Capitol Records’ Frank Holmes for the concept album’s scheduled 1967 release date. On the cover, a cartoon shop offers disembodied grins for sale. Just like the smiles on display, this box set for rock’s most legendary unfinished album comes in multiple flavors with double and quintuple-disc varieties, featuring bonus LPs and 7-inches.

All in all, some six hours of remastered music represent Brian Wilson’s milestone – a would-be, segue-filled statement of the American Dream shot through with pure harmonies that stun the human ear whether it’s trained on Bach chorales or Auto-Tune.

Despite all of this, though, this latest (and seemingly final) edition of SMiLE is not quite the real thing. But don’t tell Capitol Records.

The first person to abscond with SMiLE, metaphorically and half-accidentally, was an excessively charming Liverpudlian named Derek Taylor. As it turned out, it was a very, very good thing that Taylor engineered the heist of SMiLE from Brian Wilson’s brain in exactly the manner he did. Because Brian’s brain wasn’t quite the same afterward.

The Beach Boys hired Taylor, a Daily Express reporter turned Beatles publicist and confidant, in May 1966 to introduce Pet Sounds to a British audience. A towering achievement for the band’s 23-year-old leader, Brian Wilson, Pet Sounds transmogrified sweet post-teen anxiety into complex, moody masterpieces played by a team of California session musicians and sung by the Boys, then comprised of Brian, brothers Dennis and Carl, cousin Mike Love, and neighbor Al Jardine.

In the United States, Pet Sounds hit No.10 on the Billboard chart, a relative flop for The Beach Boys. However, with Taylor’s help overseas, it reached No.2 on the British charts and garnered a new critical respect for the band. By the time Taylor arrived in Los Angeles to work full-time with The Beach Boys later that summer, Brian was already an unprecedented dozen sessions into a follow-up single, “Good Vibrations,” in an age when most songs took a few hours at most.

Had it not been some 40 years too early for the now in-vogue term “trans-media narrative,” the then 24-year-old Taylor surely would have used it to describe what he was doing with his boss’ in-progress goods: building a story through multiple mediums.

“The excitement of a recording session transforms him into a human dynamo,” Taylor wrote in an early report titled “Brian Wilson: Whizzkid behind The Beach Boys,” one of many that he dispatched (and arranged for other writers) as Wilson held session after session. “He races from studio to control booth, in his effort to be both singer and producer,” Taylor described. In December, Brian appeared on CBS’ Leonard Bernstein’s Inside Pop television special and performed a solo piano rendition of a new song called “Surf’s Up.”

The sessions continued, as did the breathless updates in magazine features and gossip column notices that explained exactly how this new-fangled concept album was going to work. Without leaking a note of actual music, Taylor uploaded SMiLE to the world long before it was done. It would prove to be quite useful.

The Beach Boys – color band photo © 2011 GuyWebster.com – Courtesy of Brian Wilson Archive

Wilson had been recording nearly continuously since the 1961 breakthrough novelty single, “Surfin’,” creating hit after hit. These tunes were the culmination of some two centuries of American westward migration – the sunshine and golden life ebulliently written, arranged and further promised in song form. They remain licensing gold, a sound that Hollywood production companies like AudioSparx still mimick with titles like “California Vibes,” “Young Hapiness” (sic) and “Brian ‘66.”

The first manifestation of something profoundly un-sunshine-y was a panic attack that Brian suffered on a plane to Houston in December 1964. Replaced by Glen Campbell and then Bruce Johnston for road gigs, Brian stayed home to write music. And to the record-buying world with all of the Boys’ releases, that is exactly what it seemed throughout 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, and even beyond.

As he started SMiLE, he was fresh off the biggest single of his career, “Good Vibrations.” Released in October 1966, it hit No.1 in December. Seven months later, and still barely a year since Pet Sounds, arrived Smiley Smile. It contained only hints of what Taylor and others had reported. Two more albums followed within nine months. Though more SMiLE -intended songs turned up (including “Our Prayer” and “Cabin Essence” on 1969’s 20/20 and the title track of 1971’s Surf’s Up ), The Beach Boys continued to insist that SMiLE was imminent. (In 1972, Carl Wilson announced it at a press conference.)

The band never officially shelved the album. As Brian contributed less and less, The Beach Boys continued to use it to leverage credit with both underground radio and record companies and later had to return an advance to Warner Brothers when they couldn’t deliver it. The SMiLE period would later be thumb-nailed as Brian’s descent into drugs, serious depression, and years of cheeseburgers in bed. That all happened, though, a little later.

Derek Taylor left quickly. Brian wrote a song called “Busy Doin’ Nothing.” While that was increasingly true for him, the Beach Boys kept recording and touring, slowly unraveling into wooly bitterness and long-repressed family drama. They briefly returned to the top 10 in 1974 with a greatest hits album, Endless Summer, but their hit-heavy setlists only cemented their reputation as nostalgia-mongers. Lawsuits, death (Dennis in 1983 by drowning; Carl in 1998 to cancer), a Sunkist ad, collaborations with John Stamos, and more lawsuits followed.

Throughout the years, beginning with their initial surfer persona, The Beach Boys embraced countless trends, from transcendental meditation to vegetarianism to comebacks to Reaganomics to plastic surgery. (Let us please not speak of Brian’s 1989 rap single, “Smart Girls.” ) But during the 14 months between Pet Sounds and Smiley Smile, The Beach Boys played at being conceptual kings of high California culture. It has taken four decades to reconstruct their benevolent, harmony-laden reign.

Bootleg versions of SMiLE began to abound in the mid-1980s. First, Byron Preiss, who was working on an authorized Beach Boys biography, acquired a tape containing half-a-dozen outtakes. Producer Curt Boettcher got some too, and soon shared them with British collectors. For a while, the only way to hear them was at annual Beach Boys Stomp fan conventions in the United Kingdom, where they were played at the end of each weekend. Moving much more efficiently than the tapes were the legends of what SMiLE was supposed to be.

There was supposed to be a “Bicycle Rider” leitmotif linking the songs, as well as a so-called “Elemental Suite” (both true). Brian destroyed the tapes after blazes ravaged the neighborhood near the studio on the night he recorded the “Fire” segment (false). Paul McCartney munched celery on the “Vega-Tables” rhythm track (maybe). Brian recorded the Boys singing while lying on their backs (yes) at the bottom of his empty swimming pool (it’s possible).

“Heroes and Villains,” meanwhile, was supposed to be a half-hour long suite (not really) and Brian was a crazed acidhead who couldn’t function in the studio (maybe a stoner, but still a doofy human dynamo). Mike Love bullied Brian and lyricist Van Dyke Parks about imagistic lyrics like “columnated ruins domino” until Parks quit (yup). Love refused to finish his parts (thankfully, not). Brian had his grand piano placed in a sandbox under a sultan’s tent in his living room so that he could smoke hash and feel the beach under his feet as he wrote (like, way true).

Still more intriguing were the tapes themselves, filled with dubbed-down bits of instrumental exotica and scrambled modular compositions. A fan culture emerged to piece it all together. One Beach Boys freak, Domenic Priore, assembled Look! Listen! Vibrate! SMiLE! – a 300-page dossier featuring reproduced articles originally published during the album’s recording, session logs and Brian’s handwritten track list.

The SMiLE Sessions- Brian Wilson-CJasper Dailey: Courtesy of The Peter Reum Collection

“Every little piece was a major turn on,” Priore recalls. “I remember hearing ‘Child Is Father to the Man’ for the first time and thinking the piano and basslines were so ominous. The road to finish SMiLE has been extremely long. By 1989, I thought we had most of the stuff, but even that was quite short of what we could do by 1994. And even in the late 1990s, we got a major revelation because there was a tape of Brian Wilson on piano demoing ‘Heroes and Villains’ that revealed how ‘Heroes and Villains,’ ‘I’m in Great Shape’ and ‘Barnyard’ fit together. One of the real missing links was this backing track to ‘I’m in Great Shape,’ which only made it out in the last few years.”

Another fan, Lewis Shiner, wrote a science fiction novel, Glimpses, in which a time-traveling stereo repairman showed up at the sessions and helped Wilson finish. "Instead of fading where the single did, [ “Good Vibrations” ] went into a brief orchestral section, which recapped the bicycle rider theme, slipped into a few seconds of ‘George Fell into His French Horn’ and then segued, amid the laughter of horns, into ‘I’m in Great Shape,’" Shiner fantasized.

SMiLE was a perfect dream – all things to all fans. To some, like Will Cullen Hart of The Olivia Tremor Control, it begat a musical worldview. “Man, it’s everything ,” raves Hart, whose own albums became SMiLE inspired odysseys. “Conceptually, the musical stuff [is amazing] – the idea of the sections, each of them being a colorful world within itself. [Wilson’s] stuff could be so cinematic and then he could just drop down to a toy piano going plink, plink, plink and then, when you least expect it, it can fly back into a million gorgeous voices. Of course, you’ve got Van Dyke Parks’ lyrics.”

After the release of Look! Listen! Vibrate! SMILE!, Priore dubbed tape after tape of the bits and pieces that he had for inquiring musicians. “I was getting letter after letter saying, like, ‘make me five copies!,’” he remembers. He sent tapes to XTC, Gay Bikers on Acid, Apples in Stereo, and many others. To some, it was a source of income. Though the bootleg vinyl industry had long ignored The Beach Boys for being so primally unhip, SMiLE eventually began to appear on LP, often adorned with Frank Holmes’ cover art. Capitol Records nearly released the sessions again (but didn’t), and folded part of the material into its 1993 Good Vibrations box set.

Despite never coming out, SMiLE somehow even became, arguably, too hip. In 2001, cartoonist and critic Peter Bagge wrote a contrarian seven-page essay titled “In Defense of (and Praise For) Mike Love,” arguing for a Love and Carl Wilson-centric reappraisal of the Beach Boys vis-à-vis their post-SMiLE output. “[ Sunflower ] has a richness and a fullness and GLISTENING GOLDEN GOODNESS to its sound that hasn’t been matched before or since,” Bagge wrote. (Well, true.)

And, somehow, Brian Wilson got better. Not better better, but well, enough to get free of svenghali therapist Eugene Landy (a whole ‘nother story) and record some new albums. He acquired a backing band called The Wondermints, led by SMiLE collector (and Priore conspirator) Darian Sahanaja. They performed Pet Sounds live and, in 2003, announced that they would do the same to SMiLE – just as soon as Brian, Sahanaja and Van Dyke Parks finished it.

This is where things become problematic.

Wilson, Sahanaja, and Parks split SMiLE into three parts, beginning (as many Beach Boys scholars agreed) with “Our Prayer” and “Heroes and Villains,” and flowing into “Do You Like Worms,” replete with new vocal inserts. The middle act closed with “Surf’s Up” and the last concluded with “Good Vibrations,” scrubbed partially of Mike Love’s contributions and repurposed with a rave-up finale that doubled as a slam-bang finish for their live shows. Nonesuch released a studio recording in 2004.

While it made for fun listening, Brian Wilson presents SMiLE was not the same as the album at the heart of its meta-title. Its most obvious sign of forgery was its three parts – an error that the SMiLE Sessions box makes plain with its vinyl edition, which spreads the album out over three LP sides, unthinkable for an album slated to be released 1967. The less-obvious but more revealing error is in its mid-album placement of “Surf’s Up.”

“I don’t always subscribe to things Brian Wilson may say now because, a lot of the time, I think Brian is kind of reading ad copy, in a way, when you talk to him,” Priore notes. “But when the SMiLE compilation was done in 2004, Brian actually revealed to Darian that ‘Surf’s Up’ was part of ‘Wonderful’ and ‘Child Is Father to the Man.’” But memory can be a weird and unexpectedly moving part.

Gently put, Brian Wilson circa the early 21st century is not the most reliable narrator. He followed Brian Wilson presents SMiLE with a Christmas album the next year, though – when interviewed about it – seemed to betray no memory of singing holiday songs with his family in the early 1960s, despite this being a well-known story about how The Beach Boys first came together.

That the new box set uses the 2004 running order is perhaps both its greatest flaw and its happiest gift. Like SMiLE, the SMiLE Sessions might be all things to all fans. “You can walk into a Wal-Mart and buy this trippy concept album,” Priore happily notes. But in its non-finality – ready to be remade as one’s own – SMiLE remains alive in the present tense, a grin still worth grinning.