Henry Rollins Wants To Build Your Record Collection

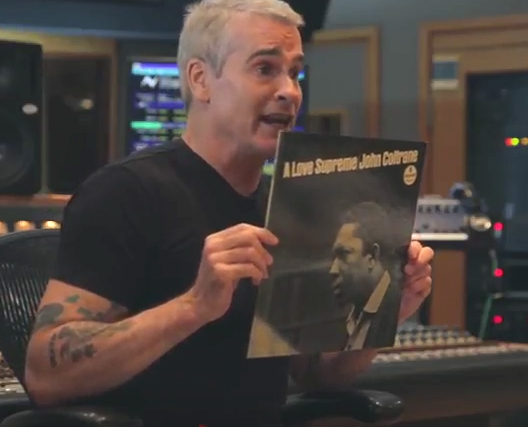

“Vacation” isn’t a word in Henry Rollins’ vocabulary. Since ending his tenure with Black Flag, the beloved iconoclast has traveled the world, written books, performed spoken-word poetry, hosted his longtime radio program and more. For his next venture, Rollins is teaming up with Sound of Vinyl, a new music curation service that sends you personalized vinyl recommendations via text message, and allows you to purchase them right on your smartphone. Rollins’ role within the company is that of a music expert and content developer, recommending his favorite albums, sharing stories from his life on the road, and conducting interviews with industry professionals. “You should check out every record that I recommend,” he says. “I’m not telling you, I’m begging you.”

Phoning from the Capitol Records building in sunny Los Angeles, Rollins was eager to discuss his new partnership with Sound of Vinyl, as well as his massive record collection (“Death, birth and divorce have given me some of the rarest records I own”) and his little-known love for the Grateful Dead.

So, just to start, how did you get involved with Sound of Vinyl as a featured curator, and what does that role entail?

A few weeks ago, I was here in this very building for the listening party for the new mix of Sgt. Pepper’s. And afterwards Jason Feinberg—one of my bosses at Sound of Vinyl—came up to me and said, “I’ve got this website, and I want you to help develop content.” And he gave me the Cliff Notes, and I said, “How about this. I like what I’m hearing. Book a meeting, and you and I will sit down for an hour and you can roll this out in slow motion.”

I came back a week later, and he said, “We’ve got this website and we’re selling high quality re-pressings—exclusive pressings that you can only get on this website. We want this site to have great interviews and educational stuff, like how to handle vinyl and how records get made. We want you to be the interviewer. We want you to be interviewed on it. To write for it, to be the face on it and help wrangle talent.” And I said, “Well, yeah! Okay.”

So basically it’s a vinyl lover’s website geared towards people who love records and people who want to get a record collection, and want to learn. So for the last several weeks, my job has been to get interesting people in the building, put a mic on them, throw two cameras on them, and I interview them about what they do. And I’ve been bringing in people that represent different aspects of the music industry: producers, artists, record company owners, mastering engineers, people re-mastering important catalogues. So when this stuff gets posted, you can go to this website, buy a record, and Ron McMaster—the great mastering engineer—will walk you through what it means to master a record. You might say “mastering” but you don’t know what you’re talking about. I want to change that. I want you to be 17 years old and know exactly what mastering and lacquer-cutting means, because you watched it on this website, and we made it really cool and really fun.

How important is it to add that human touch in our increasingly digitized world, and particularly in the increasingly digitized world of music?

It is _the_ important part. What we want is that enthusiasm, because I don’t know if you can get that from a digital source. For me, it’s holding the damn record in your hand. We want to have this thing where you can go on our site and get turned on. Like, “Wow. Henry just did his Top 10 for the second half of this year. Wow, if he likes it, I’d better check that out.” And they should. You should check out every record that I recommend—you really should! I’m not telling you, I’m _begging_ you.

What we’re doing is putting a very human stamp on the music world, which now, to a great degree, is digital. Streaming, listening to music out of your phone—that’s cool. But if you really want to connect with a band’s record, to me, it’s all about the vinyl experience. And Sound of Vinyl sells a ton of records—good ones. Old stuff, new stuff. I don’t want to be the old guy saying, “Back in my day…” Because I buy records that are coming out next month—I buy new releases. So that’s kind of the spirit of this.

“Community” is a word that is a buzzword for us. I want you as my neighbor online. I want you to come and check out what I have to say about these records… I want people to have a lot of vinyl at their house and a turntable. I want all new homes built with solar panels on the roof and a turntable factory-installed in the living room.

And with the SOV site, we’re trying to be a great vinyl destination and education destination for both an old geezer like me and 16 year old that has nothing but questions and enthusiasm and curiosity. I want to satiate all of that and have a vinyl delivery system that’s so immediate, it’s almost like you just touch your cell phone to your forehead and the record shows up. This is what we’re trying to do. We want the passion, the fun and the excitement to ooze from this site. Because that’s what vinyl does to me. I’m one of those guys that will talk your ear off on vinyl. I’ll waste your day.

Let me ask you about your personal vinyl collection. Roughly how many records do you own? Is it a living organism? Are you adding to it every day?

I don’t know the exact number. I know that it’s several feet—it’s like walls of vinyl. Two large walls of LPs and a wall of boxes—audiophile, acid-free boxes of singles. And then there’s boxes of records in different rooms. I have six stereos.

Do you organize them by genre or alphabetize them?

I listen to records in a lot of different ways. I listen culturally. You know, like music from this continent, or music from the ‘70s. But I also dig genres. I’m into the rock. I’m into the punk. I’m into the jazz. I’m into the avant-jazz and the avant-classical. However much you want to split those hairs, I’m probably into it. My record collection is basically a roach motel. My records come in, but they don’t go out. If I bought it, chances are I won’t have a chance to play it immediately. This sounds like an exaggeration but it’s not—I buy one to three records every day, which is nuts. I try to listen to five pieces of vinyl a day, even if it’s just five singles.

I have a folder of files on my computer called “I Heard That,” and I write down every record I listen to. The format, the pressing, and the order I listen to it. So I can type into my computer, “David Bowie, Dutch Pressing, Scary Monsters,” and it’ll show me what day of what year I played it.

Obviously, you have super broad taste. I don’t know how familiar you are with the history of Relix, but we started as a Grateful Dead tape-trading newsletter back in the ‘70s.

I know Relix very well. I’ve always admired the archival historical bent.

I’m curious if you have any Grateful Dead bootlegs or live records?

I’ve got a lot of cassettes, because that’s how Dead tapes came to me back in the ‘80s. I was in a band called Black Flag. Our roadie Tom was our road crew t-shirt salesman, and he was a Dead guy. He’d follow The Dead around when he wasn’t with us, and he had a suitcase of cassettes. I heard that he had the 45-minute “Dark Star” or that really fun show where Bill Graham bet the band that they couldn’t play Blues for Allah all at once, and I started dubbing those tapes off of him. Because as soon as I heard them, I just loved them. And so, with my meager earnings—I made crap money in those days—I’d buy used copies of Aoxomoxoa, Anthem of the Sun, Workingman’s Dead. Early Dead.

Then whenever we could, we’d go see them play.

And so, on a night off from tour, the band and I would drive to go see the Dead. We had a real Dead connection. We liked them and we would communicate that to their road crew—we kind of knew some of them. We’d say, “Hey, just so you know, we’re big fans.” And that got to the band, and I think they thought it was oddly amusing. I started acquiring Dead materials by ’84. And I have some bootlegs on vinyl, but mainly my bootleg stuff is cassette just because that’s how it came to me.

That’s where our magazine name comes from. “Relics” were the actual tapes being traded back and forth—these holy items being passed among fans.

And like I said to you before, that’s a community. I used to trade tapes like Nick Cave, the New York Dolls, Iggy—anything I could get. And I still know some of these people that I traded tapes with 30 years ago…Literally, friendships I have to this day because a guy dubbed me his MC5 in Sweden tape in ’84. And it’s a community of music lovers. We’re not ripping off the bands; we bought all the records. We just want more. That’s what I’m trying to get going with Sound of Vinyl: “Let’s see what Henry is listening to this month.” For me, music has always been about community. It’s about hanging out, going to the record store, having the wizened elder tell you what to buy…

Exactly. The apprenticeship aspect of it. Where you’re getting led by the cool guy at the record store. I feel like that’s kind of what you’re reviving…

Henry: Right! And now I’m that guy!

You’re the cool guy at the record store now.

Yes! That’s why I have a radio show.

I take any opportunity—I’ll substitute for anyone’s radio show just to spread music. And so, when these guys said, “Hey, do you want to help us build this website?” I kind of jumped over the table. Because this is basically me getting to make a fanzine website thing, and draw people into this great world of vinyl.

Is there a “white whale” vinyl that you’re still searching for? Something rare that you’re trying to hunt down?

Oh yeah! There’s a bunch of them. Unfortunately at this point, it’s not a record I’ve never heard, it’s a record I just don’t have that exact pressing of. The Indian pressing—literally, from India—of “Silver Machine” by Hawkwind. I saw it on Discogs like two years ago for a thousand bucks, but I didn’t buy it. And I’ve never seen one again. I wrote the guy and said, “Can you come down a little?” He said, “No. You’re never going to see this again.” And the next day a guy bought it, and I’ve never seen it again. I’ve got a bunch of those, where I’ve never heard the particular pressing, or I know there’s a test pressing or an acid tape out there. So in those cases, I’m waiting for the guy to keel over and die—or get divorced—and put his collection on sale.

That’s why he puts his collection on sale…

Death and divorce—I’m not trying to make light—but they’ve led to some of the rarest records I own. Also birth. Like, “Hey, I have a kid. I’ve got to build a new room on to the house and I’m selling off my collection.” And I’m like, “Let me take the pain away. Sell it to me!” Death, birth and divorce have given me some of the rarest records I own.

To take it all the way back to the beginning, do you remember the first record you ever bought?

Yeah, the first record I ever bought with my own money was a really awful, horrible-sounding Parlophone repressing of Sgt. Pepper’s. I had destroyed the one my mom gave me. So I went to the record store and bought another one. And even on my crap record player, I could tell it didn’t sound as good. It just sounded wrong. It wasn’t the thin vinyl; it was just poorly mastered. It sounded really high end-y. That record had been printed on my brain so hard that when I put it on, I went, “I can’t listen to this.” And I was like nine! It was like, “Am I a snob already?”

To wrap things up on a jamband note, are you into the Allman Brothers at all? Were you moved to put on Eat a Peach or At Fillmore East when Gregg Allman or Butch Trucks passed?

Yeah! I have all that stuff. As a guy who used to be in a band, those records—anything Butch Trucks is doing or whoever—that’s musician’s music. Obviously, it’s for everybody. But if you’re in a band and you hear the Allman Brothers, you realize that’s what you’re aspiring to play as good as.

That kind of telepathic playing—you hear it in the live jams. They’re just in a zone. And once you’re a musicians in a practice room—no matter what you’re doing—you’re trying to get to that point. Where you can feel the drummer, but you’re not looking. It’s like the no-eyes pass that the LA Lakers used to do with Magic Johnson—they’d play without looking at each other. The Allmans did that.

The Allmans—especially on those live records—you can feel the energy in the room. Those moments where it feels like you’re in the crowd and it’s absolutely swelling.

I had an apartment in the 90s, and I lived right behind the Fillmore East when they were leveling it. I watched the Fillmore East get leveled out of my back window. At six in the morning you’d hear everybody in that apartment wake up and go, “Goddammit!” You’d hear toilets flushing. You’d hear things slamming around because everyone got rudely awakened by the construction. But as I watched the demise of the Fillmore, I would think about that great photo of The Allmans on the road cases. I would think of that photo every morning when I’d look out the window.