Greensky Bluegrass: The Modern String Quintet

“We’re not super bluegrass people,” says Anders Beck, dobro master for Greensky Bluegrass. “We’re a rock-and-roll band—we just happen to do it on bluegrass instruments.” Beck is calling from Nashville the afternoon after the group was forced to cancel a show in St. Louis and hightail it to Music City as the highways closed behind them due to an impending Midwest ice storm. It served as an eerie reminder of the now-established Michigan-bred quintet’s hectic early touring days.

Beck, however, was not part of Greensky back in those days, when the original trio of Paul Hoffman, Dave Bruzza and Michael Bont picked up some stringed instruments and started to cut their teeth on traditional bluegrass tunes at open mics and, eventually, weekly gigs at Bell’s Brewery, in their hometown of Kalamazoo, Mich. Their slowburn rise from those casual beginnings to sold-out Red Rocks shows and a main-stage spot at Bonnaroo has allowed the band to find a comfortable niche within both the jam and string-band communities without becoming beholden to any one group of fans. Their latest effort, 2016’s Shouted, Written Down & Quoted, produced by Los Lobos’ Steve Berlin, may very well signal their arrival into the upper echelons of both scenes.

“It was a good way to keep us progressing,” Bruzza, a self-described man of few words, remembers of the band’s early days. “Because we played every week at our local brewery, you didn’t want to play the same thing all the time.”

And while Beck may not have been present at those nascent performances when the group officially formed in 2000, he has a decent guess as to how they went.

“I imagine they were pretty terrible,” he half jokes. “Just like everyone who’s starting out. But, eventually, it evolved into something pretty cool.”

These days, Greensky Bluegrass aren’t your typical string outfit, but the pull of the genre and the tradition behind it were what initially got them playing music together. “The thing that attracted us the most was the improvising and the soloing,” says Hoffman, the flowing-haired de facto frontman in a group without a true leader. “It’s a real player’s kind of music, like being in a jazz band or something. A fiddle tune is kind of like a jazz standard—you blow the head, you improvise on the form, then you blow the head and you’re done.”

Bassist Mike Devol joined the group shortly after the release of their debut album in 2004, and the band’s early touring efforts were limited, consisting mainly of playing the route to Asheville, N.C., and back, while somehow fitting themselves— plus an upright bass—into Hoffman’s Toyota 4Runner. (“Those were the good days,” Hoffman laughs.) But this still ended up breeding substantial success, culminating in Greensky winning the Telluride Bluegrass Festival’s band competition in 2006 and their subsequent main stage performance at the fest the following year. “That put a lot of wind in our sails,” Hoffman says. “You know, the pat on our shoulder we needed. To know that people who had good taste liked us was encouraging—we must be doing something right.”

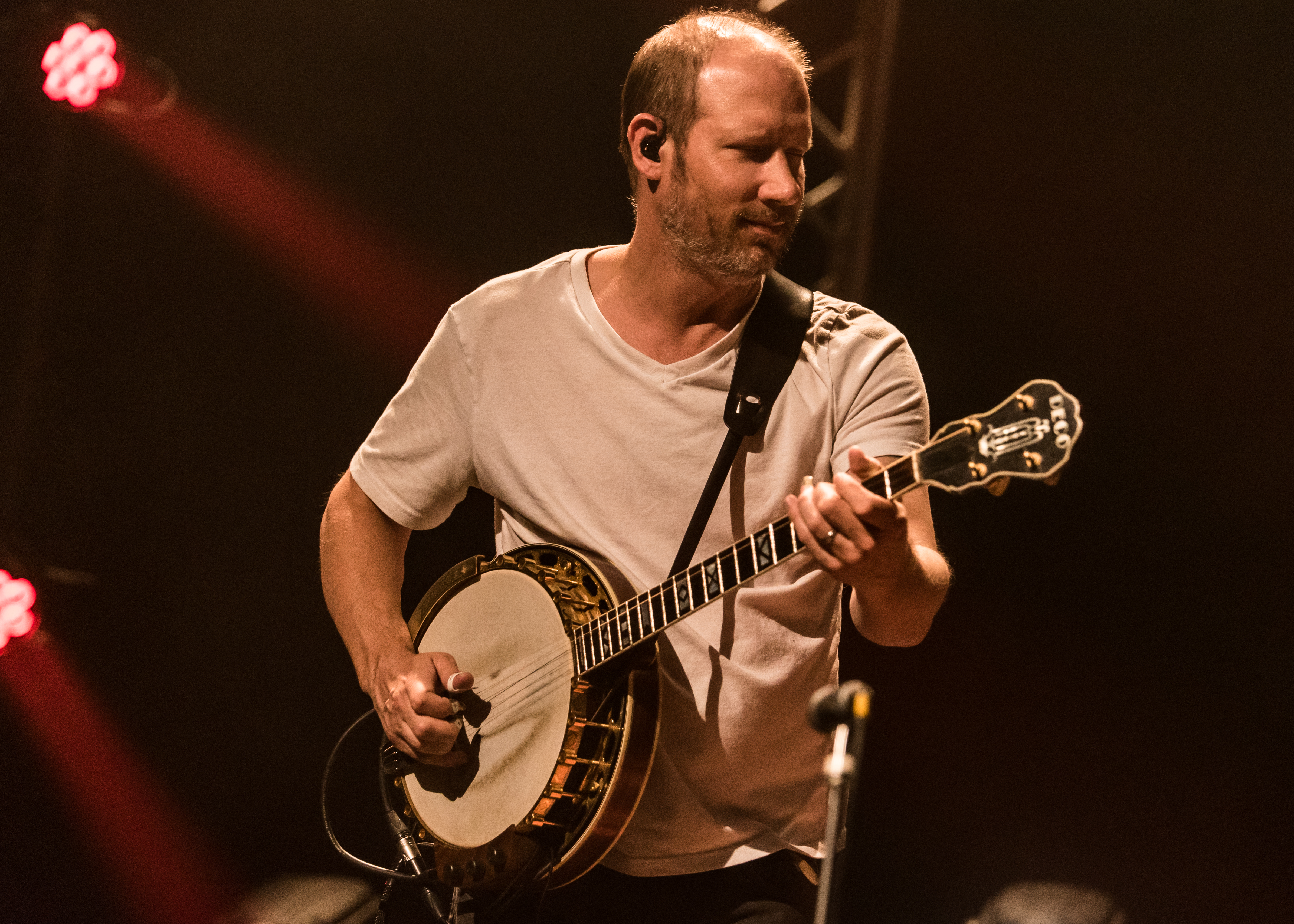

Beck joined the full-time lineup after sitting in with the band while touring with his group The Wayword Sons, with his first official show coming on New Year’s Eve 2007 at Kalamazoo’s State Theatre. Since then, Greensky have ramped up their evolution, embracing an ever-solidifying place on the live-music circuit and always looking to increase the instrumental proficiency that playing traditional bluegrass instilled in them. As Hoffman puts it: “You gotta learn the rules to break them.”

“Pushing boundaries was definitely something we all came to together,” Bruzza says. “Anders has been in the band for 10 years now, and we’ve all progressed together along those lines of open themes. Improvisation has always been important, but more so in the later years. We’ve definitely expanded on that.”

As Greensky Bluegrass’ original compositions mounted, the “trad-grass” tunes began to fall by the wayside a bit, opening the door for the extended improvisations that highlight the band’s current live show. “Early on, when we were doing bluegrass, we realized that so much of it is so similar,” Hoffman says. “We used to play these three-hour shows, and when we were playing all bluegrass songs that are three minutes long, that was lot of goddamn songs. I remember being like, ‘Why don’t we just play one bluegrass song for twice as long, instead of playing two songs that are exactly the same?’ And that’s kind of where our improvisation was born.”

With a collective proficiency now worthy of any genre from classical to heavy metal, Greensky’s improvisations continue to awe and inspire audience after audience, and that isn’t an accident. These guys are trying to jam—even though they might not fully embrace the questionable moniker of “jamgrass.”

“There’s certainly times when, all of the sudden, we’re playing a song for 20 minutes,” Beck admits. “And as long as it’s interesting, that’s cool, but if it’s jamming just for the sake of jamming, that’s not cool. Jamming for the sake of real improvisation is what we’re going for. We’re trying to go to different places each night.”

That’s not to say that the storied tradition of bluegrass doesn’t include its own form of jamming, and Greensky’s members are quick to acknowledge the master instrumentalists who have come before them and who continue to amaze while sticking to traditional ‘grass.

“In bluegrass, all the instruments solo and improvise,” Hoffman says. “Everyone’s got an important role that is simultaneously a soloist and part of the rhythmic structure of the music. That’s why it’s kind of funny—the whole ‘bluegrass jamband’ thing. Bluegrass is always jamming. That’s what people figure out when they like a band like us first, and then they go back and listen to Del McCoury records. And they never thought they’d like it, but Ronnie and Robbie [McCoury] and Jason [Carter] rip solos that shred on every song! All of a sudden, they figure that out and they’re like, ‘What?!’”

There are always inherent risks to experimentation, however, along with rewards. “In a jam, the whole band will follow each other so well, but I’ll play a wrong note—or what I consider to be a wrong note— and the whole band will go with me,” laughs Beck. “And I’m thinking to myself, ‘No, guys, don’t! That’s not where we’re going! Caution!’ But then, wrong becomes right, and something beautiful can happen out of it. It could also go the other way. But that willingness, that risk-taking, is what I really enjoy musically, and I feel lucky that the other four guys that I play music with also feel that way.”

The jamband world at large, which has had a place for bluegrass since its infancy, has taken notice of Greensky and their impressive improvisation in a big way in recent years— which makes sense, given that several of the band members are card-carrying jamband fans themselves. Greensky continue to nod to their influences too, and even devoted their most recent Halloween show to reinterpreting the range of material that Phish has covered over the years.

“That community of music fans is the best,” Beck says of the improvisational world. “We’re so lucky that they’ve embraced us and like what we do. They’re the best music fans because they really care about the music. That’s my background: I saw every single show that Phish played in 1996. That was my music; that was it for me. All of us, except for Devol, were at Big Cypress [Phish’s millennium-closing festival in Florida]. I’m not sure we even knew each other then.”

While some groups in the jamband realm gain the majority of their fame and acclaim almost solely through their live performances—while delivering studio work that doesn’t quite measure up—Greensky prides themselves on creating standalone albums that hold up under fan scrutiny, independent of their live gigs. Shouted, Written Down & Quoted presents a musically mature group that is more than comfortable experimenting with new techniques and effects.

While some groups in the jamband realm gain the majority of their fame and acclaim almost solely through their live performances—while delivering studio work that doesn’t quite measure up—Greensky prides themselves on creating standalone albums that hold up under fan scrutiny, independent of their live gigs. Shouted, Written Down & Quoted presents a musically mature group that is more than comfortable experimenting with new techniques and effects.

“The evolution of our studio music pretty naturally mimics the evolution of our live stuff,” Beck says. “One of the cool things about our band is that we can be a live band, but we can also be a studio band, whereas a lot of bands are one or the other. But we’re OK with there being a separation there. We go into the studio and try to make great records, and then we try to go play great shows, but they don’t necessarily have that much to do with each other. It’s a juxtaposition that works really well.”

With the help of Berlin, along with engineering and mastering from Michigan studio veteran Glenn Brown, who Hoffman calls “the wizard,” Shouted takes the band down roads both well-traveled and completely new.

“We hadn’t played any of the songs live before we recorded them,” Hoffman says. “And that led to a lot of openness. There was no real expectation of what they would become. And I’ve noticed too—for myself as a songwriter, and for us as a band—there’s a little less guarded pride in our ideas. It’s not like someone comes to the table and is like, ‘It should go this way.’”

Bruzza echoes this sentiment, admitting, “We were taking a different approach on a lot of the songs. It marks a lot of growth and maturity in our songwriting process and abilities as musicians. We always want to be moving forward, and that speaks to the whole jam thing. We tried some newer things that we’ve never done before, which was exciting, and also can be kind of scary sometimes, but the music was fulfilling.”

Hoffman cites album moments like Bruzza’s guitar drone in “Past My Prime” and Beck’s “triumphant” dobro tone in “Living Over” as some of the points that marked the growth of the band in the studio. “It was a fun record to make,” he says. “We had a lot more time to try stuff and just be open to it shifting and changing. It was a creative process. As instrumentalists in an acoustic quintet without a lot of the electronic options that other bands have, we’re always trying to figure out what else we can do with our instruments and how far we can push it.”

Greensky’s studio work is certainly ever-expanding and always engaging, but their live show is what mainly gets the word out about the band, especially on the festival circuit, where they have become a yearly staple. This upcoming summer, whether it is at the bluegrass-centric Blue Ox or the increasingly eclectic Bonnaroo, Greensky will encounter both diehard fans and new faces. One place where the majority of the crowd will fall decidedly in the former category, though, is at Red Rocks Amphitheatre, where the group will play for the fifth time this September, marking their second-ever headlining set at the iconic venue.

“Last year, headlining it for the first time was just overwhelming,” Hoffman remembers. “The fact that it sold out, and just seeing all those people there, in such a beautiful place, coveted by so many musicians as one of the greatest places to play. It’s been scary over the years, that’s for sure. Intimidating, but amazing.”

While Bruzza admits that his first time seeing a show at Red Rocks was when Greensky made their debut at the venue opening Railroad Earth in 2013, Beck first experienced the venue during his year-long Phish marathon in 1996.

“Walking onstage for soundcheck and finding out that our show just sold out,” Beck recalls, “there’s this element of ‘Who the fuck do we think we are?’ Because, in my mind, I’m thinking, ‘Well, only big bands sell out Red Rocks.’ And then I’m like, ‘Wait, does that mean…’ It was an incredible pinnacle in my life and career— musically and in general—and just one of the coolest things that could ever happen.”

If there was ever a watershed, “now we’ve made it” moment for Greensky Bluegrass, it was that night, when they stepped onstage for their own sold-out Red Rocks performance, in the same state where they got their big break at Telluride nine years earlier. And Hoffman, for his part, didn’t let the experience pass him by without some reflection.

“When we were a younger band, there was that pressure going into a bar where no one knew who we were, and you had to prove yourself,” he says. “And now, there’s this opposite pressure: We’ve proven ourselves to these people and we have these expectations to meet. They travel really far and they work really hard to see us, and I think that pressure is far more intense and important to me than the other one. You know, put us under a fake name and go throw us on a festival somewhere, where no one knows who we are, and I’m not that scared to do what we do and charm them— they either like it or they don’t. But send thousands of people all the way across the country to see us, and that pressure is more palpable. I take it really seriously. I always tell people that my motto is: ‘Every show should be better, harder and longer.’ Which is difficult to achieve, but I try every damn time.”