Exposed: Q&A with Burning Man Cultural Co-Founder and Aerial Photographer Will Roger

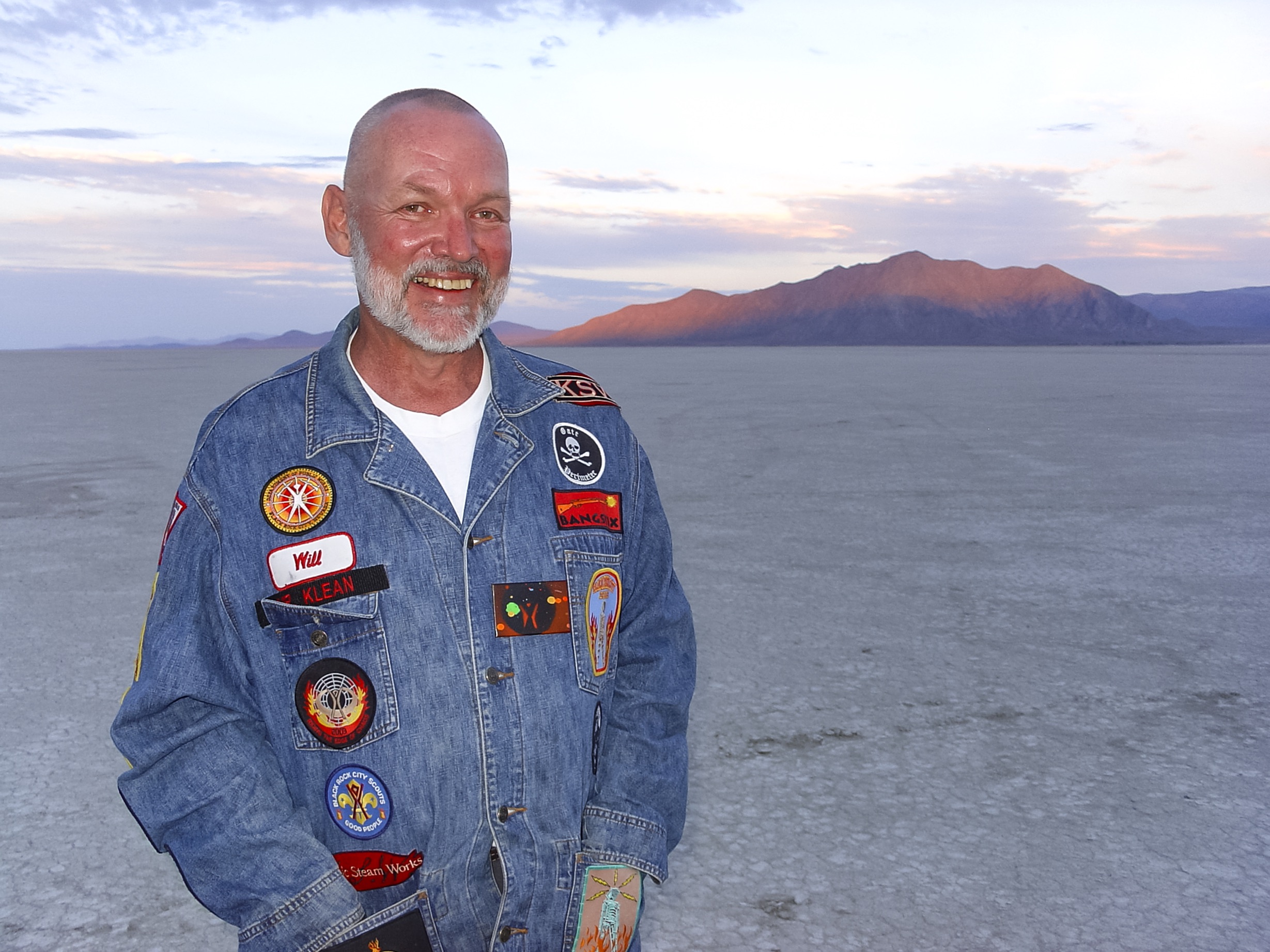

For the upcoming September 2019 issue of Relix, we spoke with Will Roger, a cultural co-founder of Burning Man who has been with the festival for nearly two decades. Roger recently release a book of aerial photography of Burning Man’s Black Rock City, Compass of the Ephemeral. Below is an extended Q&A with Roger featuring material not published in the issue.

“The key words are ‘Burning Man community,’ as compared to what we call the ‘default culture’—the culture we live in outside the event, where people often feel separated from each other,” says Will Roger. “When at Burning Man, the ‘10 Principles,’—[along with] unconditional love and overpowering creativity—are some of the things that make Black Rock City different from the default culture and powerful as a life changer. The culture of Burning Man provides an opportunity to celebrate the world and humanity in an authentic expressed form.”

As a cultural co-founder of Burning Man, an annual weeklong communal gathering in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert in late summer, Roger has been a part of the event for 25 years. He first discovered Burning Man through his life partner and inspiration, Crimson Rose, in 1994; together with several others, they are also co-founders of Black Rock City, LLC, the company that has produced the event for almost 20 years.

A favorite memory that stands out for Roger took place in 1997: “It was the year we transitioned from a casual campout with friends to becoming Black Rock City, a real city in the desert. It was the first time we to had to apply for permits, hold a business license and create mechanisms and processes to support a city. It was an incredibly creative and collaborative experience. Every day was filled with magic.”

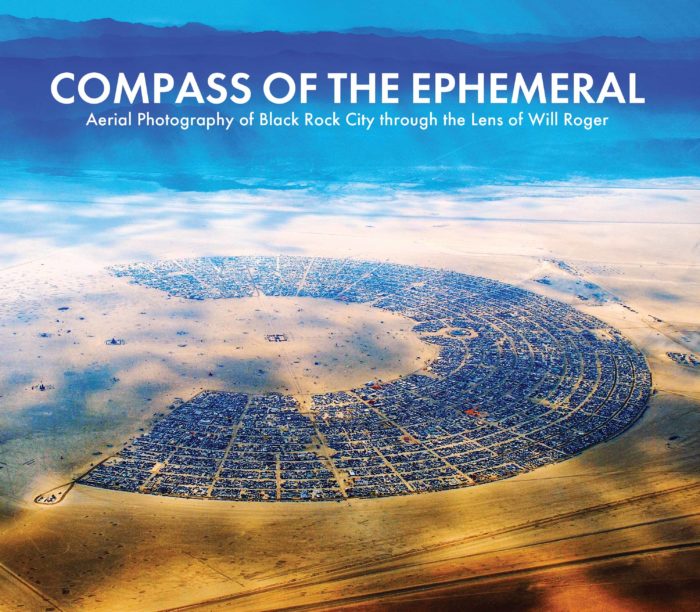

Though Roger has been a photographer for several decades, this is his first book of aerial and drone photography,Compass of the Ephemeral: Aerial Photography of Black Rock City Through the Lens of Will Roger, published earlier this year via Smallworks Press. The book includes a collection of his photographs documenting the Burning Man build-out as the desert space transforms into a temporary city. It includes additional art and photos chronicling the history and evolution of the global community that has grown to support over 70,000 citizens, as well as historical and artistic essays.

In addition to documenting the ephemeral cityscape of Burning Man with his camera, Roger founded the Black Rock City Department of Public Works (DPW), a team of hundreds of volunteers who manage the logistics and production of the event, including building and deconstructing its physical infrastructure. He actualized an FAA approved airport and started traditions like the Gold Spike Ceremony ahead of the event, celebrating the builders of the future city each year. Roger also focuses on conservation efforts for the Black Rock Desert.

Each year, Burning Man culminates with the symbolic burning of a large wooden effigy (“The Man”) and Black Rock City—which becomes the fifth largest city in Nevada for a week in time—vanishes without a trace.

“The freedom to explore all art forms on such a massive scale is an incredible phenomenon and experience,” Roger says. Here, he shares some of his original photos as well as other images from his book, as he takes us through a visual history of the Burning Man community.

Did you have any idea that Burning Man would become a global movement and cultural phenomenon when you first started out?

No, not at all. It was a campout with friends—hanging out, having a good time. Luckily, from the beginning, it was all the right people. Then other people wanted to join and it grew organically. In the beginning, we didn’t talk about changing the world. Year by year, at the end of each event, we started thinking about next year. In the ‘90s, there wasn’t that many people. Once the Burning Man regional network began, we then realized that we had created something special.

How long have you been documenting the experience with photos and drone photography?

I have been photographing for a long time, but I lost a substantial part of my portfolio due to a digital systems crash. In 2005, I was offered to go up in a plane. I decided to take pictures as I had experience doing aerial photography. The pictures came out great and I give the prints away as gifts to our staff and cooperator agencies. The photograph featured on the cover of my book is part of the traveling museum exhibition, “No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man.”

I started drone photography five years ago. At Burning Man, you must have a permit to use a drone. We don’t like a lot of drones flying around, and there are only 30 registered drone pilots every year. I try to go out and fly my drone whenever I can in the morning. There is hardly any wind at that time. I usually spend two or three mornings with the drone when the weather cooperates.

You discovered Burning Man in 1994 via Crimson Rose—how do you and Crimson Rose still inspire one another today?

We have been together for a long time and it is a powerful, loving relationship. What we have nurtured in each other is our independence. We allow each other to be everything that we can be as individuals. We [don’t] need the other to make us feel whole. It is the inspiration to be a better person for ourselves that cultivates our relationship to each other.

What sort of process is the build-out and setup like? (How many people and what sort of scale?)

Several thousands of people are involved. Preparations begin months before the event. In my book, I talk about the Gold Spike, the first stake in the ground to survey the city. Once the survey commences, it will take one month to build. There are many departments responsible for different aspects of the build. These departments work in harmony and it is truly a magical thing to witness. Moving materials, installing art, and the coordination of people, camps and structures are all carefully choreographed.

Talk about the art cars and artistic contributions of festivalgoers and how this creative exchange of ideas came to be?

Again, it’s one of those organic things that happened. In the first couple of theme camps, people just got creative and began to expand on ideas. It was probably in 1994 when someone showed up with an art car. Then someone salvaged a yacht from the crusher and put it on wheels. Someone else decided to build a massive shark on wheels. Next thing you know, the yacht is trying to catch the shark and a great chase ensued. People became inspired by such shenanigans and imaginations grew.

We now have the Department of Mutant Vehicles (DMV). People must register their vehicles for day or night use or both. Safety is paramount. I think the art cars are very interesting because they are so unique to Burning Man.

Would you describe the temple as a sacred space? What purpose does it serve for the community?

The temple is very much a sacred place. It becomes a memorial to the trials and tribulations of what it is to be human. Burning Man is loaded with energy, but the temple is so sacred that, by Thursday or Friday of the event, you cannot help but feel that energy and the power of the place. Burning the temple on Sunday night brings closure. It truly is one of the most powerful experiences of the Burning Man event.

Where did the idea of burning an effigy at the end of the festival come from and what does this mean to you?

It started at Baker Beach. There was no real focus of what it meant, but everybody brings their own intentions—whatever it means to them. I think that that holds true today. We don’t have a dogma or a message to give. Bring your own meaning!

Tell me about the site’s “leave no trace” mentality. What’s it like to go from having thousands of people onsite one week to appearing like no one has been there at all the following week?

After the event, our staff and several hundred people are onsite for a couple of weeks to meticulously remove every foreign object. In total, it takes a month to leave no trace.

“Leave no trace” is a mentality, an intention. If something falls to the ground, then pick it up. We ask people to take away all of the garbage that they brought with them. We teach our community to be responsible for everything.

A version of this article appears in the September 2019 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.