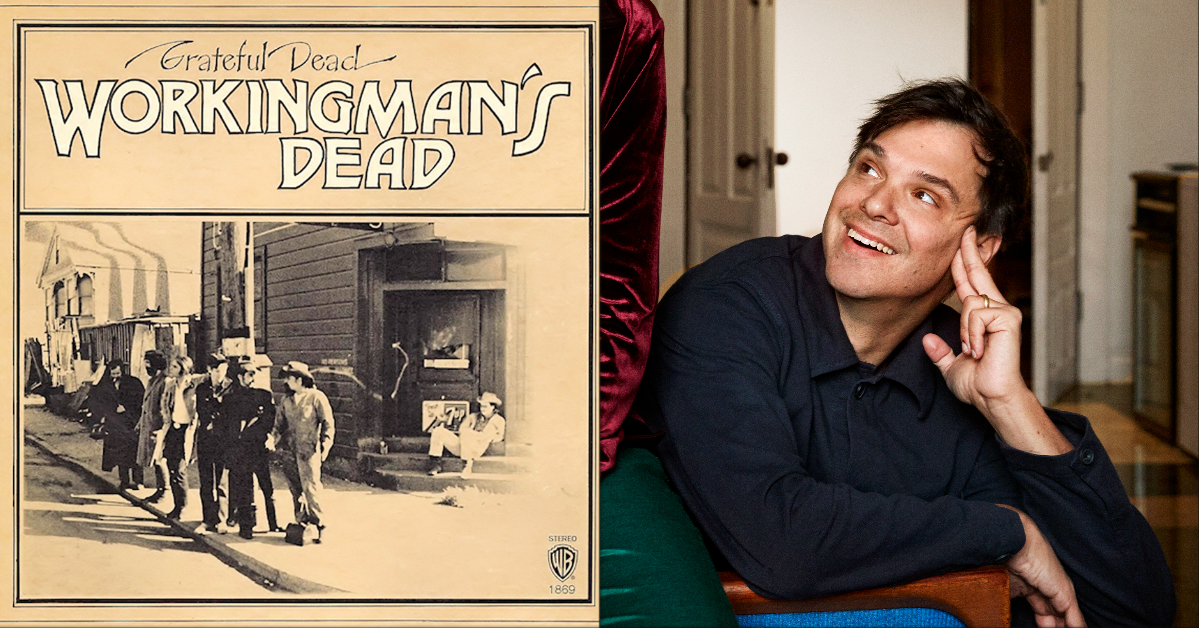

Dirty Projectors’ David Longstreth Reflects on ‘Workingman’s Dead’

For Vinyl Me Please’s upcoming Anthology: The Story of the Grateful Dead, a number of modern musicians were enlisted to pen liner notes about their favorite GD releases.

One such individual was Dirty Projectors’ David Longstreth, who took a deep dive into the band’s California Country opus, 1970’s Workingman’s Dead.

Click here for a chance to win the entire VMP Anthology: The Story of the Grateful Dead set.

Below, the Dirty Projectors frontman shares his thoughts on the classic LP…

The story of Workingman’s Dead is that it’s an about-face from the baroque acid-tinged psychedelia of the Grateful Dead’s early work into sepia-toned Americana. It is one of a crop of records between 1966-1970 — including John Wesley Harding, Sweetheart Of The Rodeo, Beggars Banquet, Let It Be and others — that abandoned the paisley and sage of the mid ‘60s for sounds tinged with country, roots, folk and bluegrass. This was music for getting out of the cities and going back to the land — “workingman’s music,” as Garcia noted to Robert Hunter.

My parents’ old, tattered copy of Workingman’s Dead was in constant rotation in our household when I was a kid: music for washing dishes and petting the dogs. It was a long time before I became aware of the album’s status as a sort of Boomer cultural bible: a back-to-the-land grail. In what might’ve been the last radical act of their radical ‘60s selves, my parents moved in 1973 from the Bay Area — where they saw the Dead at the Fillmore a half dozen times — to rural Upstate New York, to start a small farm. Personal particularities aside, they were, in a way, following the Workingman’s Dead manual.

So the paisley and sage of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s Bay Area was my mythical prehistory. The sepia-toned Americana was where my brother and I began. It’s funny to think that when I was 29 — just a year older than Jerry when he was making this record — I too moved to a remote part of upstate New York to make Dirty Projectors’ own back-to-basics album, Swing Lo Magellan. To me that feels like a testament that the roots of Workingman’s Dead go both backward into the past and forward into the future.

Articulating an archetype as it emerges: there’s not a much higher achievement for an album!

Workingman’s Dead is a great album for a lot of reasons. From the purple mountains’ majesty of inventive steel guitar and pedal steel (“High Time,” “Dire Wolf”) to the fruited plains of goofy choogles (“New Speedway Boogie,” “Easy Wind”) and the nimble flatpicking and banjo (“Cumberland Blues”), this album is a nation of guitar. Also, I just love the sound of Jerry’s guitar through the Leslie rotating cabinet on “Casey Jones” and “High Time.”

These songs are harmonically unorthodox, with progressions both lyrical and inspired. The surprising minor key outro of “Uncle John’s Band!” The mid-phrase key change in “High Time!” The ninth chords in “Black Peter,” which feel almost like Satie moves! And, lest it all get too muso, this album plays yin to its own yang: for every wonderfully non-repeating labyrinth like the bridge of “Dire Wolf,” there’s a two-chord blues workout like “Easy Wind.”

The way the drums drop in on the second verse of “High Time” — quietly, stuffed entirely into the right channel, but full of character — feels emblematic of Kreutzmann and Hart’s approach. What a melodic and sensitive double-rhythm section team! There are so many details in the kit playing and percussion that elevate these recordings: the brushes on “Black Peter,” the guiro on “Uncle John’s Band,” the handclaps and maracas (mixed surprisingly loud!) on “New Speedway Boogie,” the beautiful snare tuned high on “Uncle John’s Band,” and elsewhere. The carefully calibrated dynamics and drum tuning throughout are really marvelous.

And let’s not forget: the singing is pretty incredible too. Jerry, taking lead duties on every song except the Pigpen-fronted “Easy Wind,” is at his most commanding and soulful. (“New Speedway Boogie,” “Casey Jones,” “Dire Wolf” and “Black Peter” are particular faves). His performances are brought into sharper relief by the blithely loose harmonies from Bob, Phil and Pigpen that pepper the record and remind me, happily, more of the Wailers than of the Dead’s smoother Californian contemporaries like Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young or the Byrds.

There are the occasional hokey old-time tropes about miners and trains and gin — which, hey, Jerry almost pulls off — but many of these images and rhymes have a kind of legitimately out-of-time uncanniness. “Come on along or go alone, he’s come to take his children home” sounds like a lost couplet from a 300-year-old nursery rhyme. These songs feel like stories, but often the particulars aren’t quite clear — like old tales that have shed so many details in retelling that they’ve lost literal sense, but acquired a kind of sculptural presence.

And that’s what Workingman’s Dead is to me: a totem — of America, of a band — in vibrant, blooming transition.