Behind The Scene: Linda Wolf on Two Generations of Mad Dogs and ‘Cocker Power’

Photographer Linda Wolf was only two years out of high school when she took to the road with Joe Cocker and Leon Russell on the Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour. Shortly afterward, Wolf relocated to Provence, France, to attend the Institute of American Universities and L’Ecole Experimental Photographic. Her portraits of villagers in the South of France are now exhibited in galleries across the globe. She has gone on to teach photography at the college level, produce a number of critically heralded mural projects, release a few books (including Daughters of the Moon, Sisters of the Sun: Young Women & Mentors on the Transition to Womanhood) and create the nonprofit organization Teen Talking Circles.

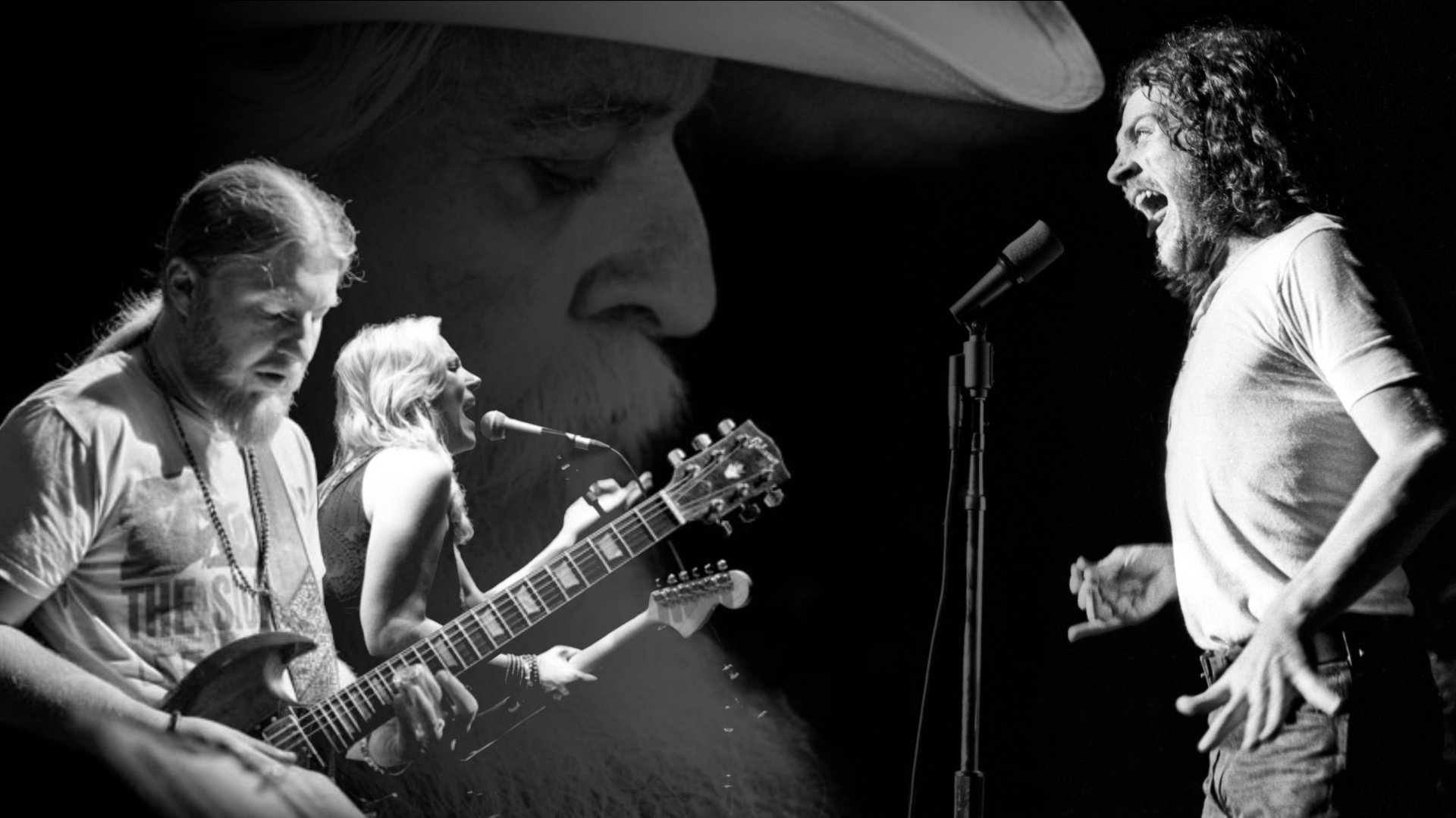

Still, as Wolf explains, “music has always been my first love.” So, in 2015, she eagerly accepted an offer to become the official photographer for the Mad Dogs & Englishmen reunion event at LOCKN’. Her new book, Tribute: Cocker Power, honors that legendary 1970 Joe Cocker: Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour, as well as the more recent celebration at LOCKN’.

What initially drew you to photography as a medium?

Images were always a part of my life. My father was a cinematography major at USC and also one of the stuntmen for Johnny Weissmuller when he was a teenager. My mom was a fashion model before she became a university professor. My grandmother was the righthand person to Sol Lesser at MGM, who was the producer for the Tarzan movies. Also, my grandfather was the owner and manager of the Lincoln Theater, which was referred to as the “West Coast Apollo.”

So I grew up around the industry, and my dad would document me endlessly. He also put a camera in my hand when I was young. Before I was even a teenager, he gave me an old Kodak box camera that I used to shoot the county fair. So I just got interested in recording through him.

Photographing people helped me express myself. It was another way for me, as an only child, to research how to be a person in the world. That’s how I learned how other people lived—what was going on inside them and how I could compare that to my own growth process. I wanted to convey what was going on inside the person. I wasn’t interested in the superficial; I didn’t fit in at school. I was always sort of an outsider—one of the peace freaks, the flower children, the hippies. We were outsiders in this system. I wanted to look inside of people; I wanted to know what was really going on.

Early in your music photography career you shot Fanny, a group of women who, much like yourself, defined their own path. How did that come about?

First of all, as a young teenager, I was a Beatles maniac, a Rolling Stones maniac, a Dylan maniac. And I was also into the blues. I got backstage at a T.A.M.I. show, where I met all The Rolling Stones when I was 14. So I was just totally into music as an expression of my feelings. Since I hadn’t quite started using my camera as an expression of my feelings, I was mostly doing that through the music of the day.

A bit later—I must’ve been about 17 or 18—I needed to earn some money, so I went over to Reprise Records, hoping to be a temporary worker. I couldn’t type but I guess I looked good enough to be a secretary. My office was next to Richard Perry’s secretary at Warner Brothers, in this big open office situation where all the secretaries were. Richard came over to me one day—his secretary wasn’t there—and he said, “Look, this all-girl rock band that I just signed is coming in and I want you to make sure that they’re taken care of.”

I’d been there for about three weeks when June [Millington], Jean [Millington], Alice [de Buhr] and a couple of other women came strutting down that aisle. Normally, it was always guys so I was taken aback. I was already a feminist and I was just like, “Hey, who are you?” We talked a bit and they asked if I played piano. I told them I did, so they asked me to come over that night and try out for the band because they were looking for a keyboardist.

I went over to Fanny Hill that night and we all had a great bond. We were all synced, in terms of our motivation as young women who wanted to be more than just secretaries or receptionists sitting around. We really wanted to be part of the music. I played for them but, unfortunately, I didn’t play well enough to cut it and join the band. But we liked each other so much that June said, “Why don’t you just be our photographer?” I said, “That would be perfect.” So I moved in and took my dad’s Nikon. June gave me her father’s camera—this beautiful old Leica—and there was a dark room behind the rehearsal room.

So it was all set up for me. It was this perfect entry into having a full presence with a band, full permission to shoot everything and anything. Whether we were baking muffins that day, running around naked or whatever, I had the freedom. At that time, freedom was the word, and, as a photographer, I had all the freedom in the world.

What led to the Mad Dogs tour?

My old boyfriend, Sandy Konikoff called me up and said, “There’s a rehearsal starting tonight at A&M Records. Can you drive me there?” I thought I was just dropping him off, but I went in and that’s when I met Denny Cordell. I saw what was going on and I said, “Oh, my God; I want to go on this.” And he said, “What can you do?” I said, “I can be the photographer.” And he said, “Show me something.” I saw that Jim Gordon had a camera. Jim had gone to my high school. I didn’t know him, but I went up to him and asked him if I could borrow his camera. There was some guy following me around who said, “I have a dark room,” and I said, “OK, great.” So, I took some pictures, went to the dark room, and came back with damp proof sheets. I showed them to Denny and he said, “OK, you can go.”

I was 19, so I was still living with my parents at the time. But I went to them and said, “I’m going on a rock-and-roll tour in six days and I’m moving into Leon Russell’s house tonight.” I left with what clothes I could fit into a small suitcase and the camera my dad gave me, and moved into Leon’s. All kinds of things happened during those six days. I also shot the rehearsal, but I have no idea where those films are. I don’t know if I gave them to Denny or if Denny ever processed them, but nobody ever gave them back to me, which is too bad.

It was an amazing time—an extraordinary experience. I was this nice, middle-class young woman. I was one of the youngest people on the tour and, by the third or fourth day, I had figured things out. Leon had said, “You can dance at the front of the stage; you don’t always have to take pictures.” But I really never thought I would do that. It felt like a cheap thing to do. I thought I would look like a go-go dancer, which is the last thing that I wanted to be. I was a hippie flower child, but, by the third show, I was dancing my ass off onstage. I was just really loosening up, freeing myself and growing up in so many ways. I achieved my goal, which was to be fully part of the music on that level and to have the freedom to be creative, expressive and deep. I could really get inside the people I was shooting. Like with Fanny, there were no prohibitions. It was not “I should be in the pit for the first three songs.” I didn’t even know what the pit was. I was onstage the entire time or I’d go out into the audience and come back. I just had complete and utter freedom.

When you think back to the Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour, what’s the first image that pops into your head?

I’ve seen that picture of Joe in the spotlight a thousand times. There are so many moments from that tour that are profound. If there were categories, then they’d be: What was the sexiest moment? What was the moment I discovered my own need for the limelight? What was the moment that I got in trouble? What was the moment that I got saved from being in trouble? What was the moment I lost all my luggage? What was the moment my father came and my mother didn’t and why? What was the moment my grandma came to the hotel with us after the show with a button on her lapel and people kind of freaked out that she was a really strange weirdo wearing a “Cocker Power” button. What was it like getting on the plane? What was it like being on the plane? What was it like being on acid on that tour? There are just endless moments that stand out in my mind. Some of them are just these strange, ephemeral, dreamlike states. I would say the majority of the time, 99 percent of us were giving everything we had and it was amazing. I was exhausted when the tour was over and my mother put me in bed for a week.

To what extent do you think the early photos you took of these performers informed your later work outside of music?

My friend Mimi DeBlasio once said, “Music is love.” The reality is: I grew up with music that had many levels of deeper meaning inherent in it. Like Bruce Springsteen said we learned more in a three-minute song than we learned in school. So, for me, I feel like I grew up at the perfect time. The music was a sound track to those times. I was influenced by it all – the music, the politics, the social justice movements, and the freedom – the freedom to be alive. It was all about being real, and authentic, and honest and open, and I incorporated all that into my being and my work going forward.

As a photographer, that made a huge difference because people trusted me just by my vibe. So I could go into various cultures and make friends immediately with people because I didn’t seem threatening and I was just trying to take their picture. I was after self-discovery and mutual relationships, which is what I got in the music industry from the very beginning. It’s this mutuality, being part of something together—being expressive together—that really influenced me. And it’s lived with me ever since.

When I photograph people, it’s not about getting something from them; it’s about sharing something with them— something that’s as human to me as it’s human to them.

I saw Leon Russell, both at rehearsal and onstage, at LOCKN’. He seemed reserved, offering guidance in a quiet way. Is that how he was in 1970?

Well, anyone close to Leon will tell you that he was agoraphobic. He holds back a lot and observes—he’s taking it all in. Sometimes Leon would expose himself, but he was mysterious, he was withdrawn and it was difficult to get to know him. Having said that, he was much more emotional in 2015—he’d already been through brain surgery. I know he and [drummer] Chuck Blackwell wept with each other pretty much daily, just hugging and having these small little moments because they had known each other since they were teens.

Leon had changed an awful lot, but he was still very reclusive and shy. His nephew told me that he got into the car after some of the rehearsals and he would say to his wife, “I think they like me, I really do, don’t you?” I mentioned this to Derek [Trucks] who told me, “Yeah, we were saying the same thing. I think he really likes us.” And he did. He had tremendous love for Derek and Susan [Tedeschi]—he wrote songs for her after the tribute concert.

How has the 2015 Mad Dogs reunion at LOCKN’ impacted you?

I feel like I fulfilled many of my dreams and longings. I feel fulfilled. I was able to honor and pay tribute to everyone involved and thank them. And I’m particularly thankful to help keep Joe Cocker and Leon’s legacies alive, along with everyone else who was involved. Creating relationships with these people as human beings—that, in itself, has been very fulfilling. It was great to be able to reconnect with all my friends from the past as adults—as mature people. It’s been lovely—particularly reconnecting with my female friends from the band. There’s this deep sense of fulfillment in me, this sense of belonging. It makes me feel like I can move on with my life in areas that matter deeply to me.