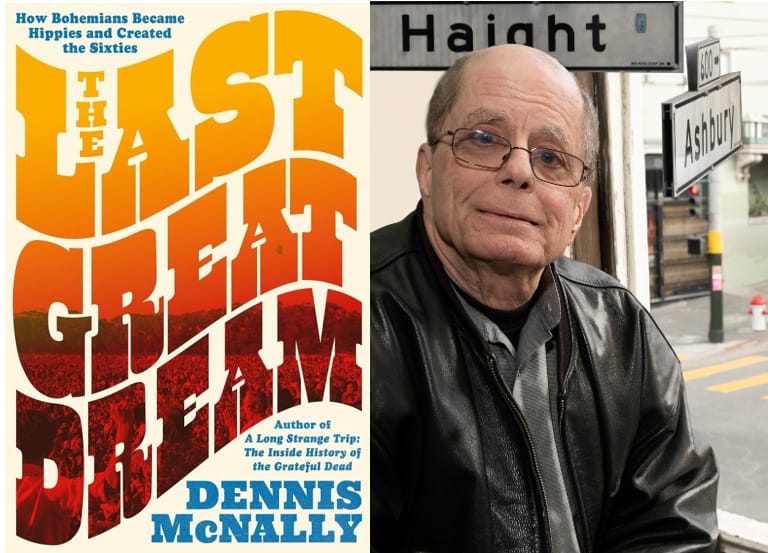

Dennis McNally’s Last Great Dream: Working with the Grateful Dead, Tracking Kerouac and Exploring How Bohemians Became Hippies

“Starting in World War II -era San Francisco, a thread of artistic discourse focused on freedom coalesced into a subculture,” Dennis McNally writes in the introduction to The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties. He adds, “It was not premeditated, ideological or planned; it simply happened… What was remarkable about the Haight scene was that it took the insights of a small group of avant-garde artists and made them accessible to the better part of a generation through music and culture, with ripples of influence that in many cases have only grown since 1967.”

The Last Great Dream, which takes its title from the Bob Weir song “Two Djinn,” is McNally’s fourth book. The first of these, Desolate Angel: Jack Kerouac, The Beat Generation & America (1979) started as his doctoral thesis in history at the University of Massachusetts. From there, he began an extended stint as the Grateful Dead’s publicist, after which he completed his biography of the group, A Long Strange Trip (2002), which he had initiated prior to working with the band in an official capacity. This was followed in 2014 by On Highway 61: Music, Race, and the Evolution of Cultural Freedom.

McNally acknowledges, “What I eventually came to realize is that all four of these books connect. I never anticipated that I was going to have a life pattern of writing a cultural history of bohemia in America after World War II, but that’s how it turned out.”

In thinking about the throughline across your work, let’s start with the Kerouac book. How did that come about?

I got incredibly lucky. I was sitting around one night talking about the Beats. This was 1971, and I was thinking that most graduate school history departments would never allow you to address a subject as recent as the Beats. Then a friend of mine said, “Do Kerouac. His papers are at Columbia.”

He was a graduate student in math, but the great good fortune of my life is that all of these things have just popped up. As it turned out, while my dissertation director was a Civil War historian, he also loved the idea of doing something literary. He thought Kerouac was literary and bingo! I got incredibly fortunate.

My friend also said, “You can stay with my friends in the Bronx.” That’s where I met a number of people who are still very dear to me, although, unfortunately, my friend has passed away.

That same friend turned me on to the Dead. From there, I moved onto becoming a Deadhead and, eventually, I became their publicist because I needed a job and they needed a publicist. It just rolled from there. I did very little in the way of making conscious decisions.

Kerouac died in 1969, at which point scholarship about him was at a nadir. Did it feel like you were rowing against the current?

Oh, wildly. Remember, I’m not a literary scholar, I’m a historian. I was interested in Kerouac in a couple of contexts. One was that he was a kind of diarist. His writing was not only based on his own life but also this decision to write in a style that was completely opaque to most American readers.

The whole idea of what he tried to do with On the Road and then, in particular, with Vanity of Duluoz and Visions of Cody was to write what he heard, which was jazz. That was something he knew about. So I just kept following it.

After the publication of Desolate Angel, you had an inkling that you’d like write about the Grateful Dead in a similar form. How did you approach that?

I recognized that I couldn’t just march up to them and say, “I want to write a book about you.” What I did intuitively know is that Jerry and Kerouac had a link. So after I completed the Kerouac book in the fall of ‘79, I mailed copies of the finished book to Jerry and Hunter. Then I just sort of waited. I had no idea what to do. The band’s phone number wasn’t readily available.

Then I decided that I would write an article about New Year’s as a ritual for the San Francisco Chronicle. So on 12/31/79, even though I was sicker than a dog, I went to the show. In January of ‘80, I interviewed Bill Graham, who was quite accessible. At that point, I experienced some Grateful Dead karma. I came out of the interview and Bill’s assistant, Jan Simmons, said, “Have you talked with Eileen [Law] yet?” When I said no, she said, “Well, here’s her number.” The way I got the Grateful Dead’s number was a Deadhead at BGP handed it to me. All this stuff was just perfectly in synchronicity.

I went to see Eileen and we ended up talking for two hours. She came to the office on her day off and we schmoozed. Eventually what happened was that, in the fall, when they were preparing for the Franken and Davis skits for the Halloween shows at Radio City, they said, “Eileen, bring us some Deadheads.” The idea was that you would tell stories of your adventures on the road.

So I went there, met Jerry and subtly mentioned the Kerouac book. He got very excited because Kerouac was really important to him. Then this idea sort of percolated and a couple of months later, I met with Alan Trist and Rock [Scully] at the Warfield during the December 1980 Dylan run. They told me: “Jerry says, ‘Why don’t you write a book about us?’” At which point I said, “Gee, that sounds good. I might be able to f it that into my schedule.”

In 1984, you became the band’s publicist. To what extent were you able to work on the book while also functioning in that other role?

In 1985, I tried to do both simultaneously, which was insane for a number of reasons. One is that the mentality of being a historian is not the same as being a publicist. Of course, I didn’t know what a publicist was since I’d never been one.

The way that came about was that at some point, they decided they needed a publicist. So Jerry said, “Get McNally to do it. He knows that shit. Send him up to my house and I’ll tell him what to do.”

So I went up to his house and he said, “Well, first, we don’t suck up to the press.” I went, “OK, got it. Don’t suck up to the press.” I might’ve even written it down. [Laughs.] Then he said, “Really, that’s about it,” and he fired up a joint. We spent the rest of the afternoon shmoozing.

What it boiled down to was that it was simultaneously the easiest job in the world and the toughest job in the world. I had to deal with things like the crew and the arcane oddness of the way the Grateful Dead fit together. But at the same time, the band wasn’t nagging me for coverage or attention. They said, “We don’t give a shit.” That was the last thing in the world they cared about. The only person that ever wanted PR was Mickey, who had these odd, wonderful projects that were really quite interesting.

When people wanted to talk to Jerry, he would honor the request if I thought it was important. He was the best boss in the whole world. You would get Jerry if it was something interesting. For instance, we did an interview with Buck Henry, who was the room clerk in The Graduate. The last interview Jerry did was for AMC’s The Movie That Changed My Life. They pitched me and I immediately said, “Aha!” At that point, I hadn’t done an interview with Jerry in a year because it’s not as though we needed the press. The question was, “Do we want to do this? Do we need to do this?” Typically the answer was, “No, let’s not bother.”

But I got that one, and it was hilarious because it was Garcia Band at the Warfield and I went in the dressing room and I said to Jerry: “I think I finally have something interesting for you.” And he said, “Well…” I said, “The movie that changed your life,” and he immediately sat down and did the interview for me [on Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein]. He loved talking about Abbott and Costello, and his childhood memories and all this stuff. It was fun. That he wanted to do, the other stuff, ehhh.

What precipitated the decision to write On Highway 61?

I went from Kerouac to Grateful Dead, and when I had finished the Kerouac book, I fell into a pretty serious postpartum depression. So I recognized that I should have some idea of what I want to do next. Eventually, what I realized—although it took me a long time to figure it out—was that I wanted to write about how white people got their ideas of hipness. I started around 1850 with the origins of corporate culture and realized that it was a consequence of following Black culture.

On Highway 61 tells the backstory of the elements that would become things like Kerouac following jazz. Before that it was ragtime. Even earlier, with Thoreau, it wasn’t Black music because he had no knowledge of that, but it was about abolitionism and social philosophy. It goes from there through Twain and on up into the 20th century.

What led you to The Last Great Dream?

I was proud of how On Highway 61 all fell together. After that, I sort of knocked off for a year and read books that weren’t research for the next book. Then what happened was I got hired by the California Historical Society to curate a photo show celebrating the Summer of Love. This was in 2016, and the next year was the 50th anniversary, which was a very big thing in San Francisco. So I started working on that and about a month into it, I suddenly went, “You idiot, this is your next book. This rounds it out. This is what you’ve been after all along.”

At some point, somebody’s going to ask me: “What was the biggest surprise you encountered in researching this?” The real surprise was that nobody had done it before. All these people had done books about the Summer of Love, but none of them approached it from a deeper point of view. So I started poking around.

The photo show ended up starting with the Beats because there was a limit to how much room was available on the walls of the display space. But then once I started thinking about it, I went, “All right, I’ll start with the poets, in particular, [Kenneth] Rexroth.”

So I started with what was called the San Francisco Renaissance. That’s Rexroth, [Robert] Duncan, and then you get in a bunch of other poets. From there you get in the artists at the Art Institute and it all f lowed downhill.

I find that poets are often overlooked in works of cultural history.

Well, it all connects. In my life, you go back to On the Road and, before that, to the Beats and Allen [Ginsberg] reading “Howl” at the Six Gallery and all that stuff just sort of comes together. The Six Gallery was so-called because there were six people who contributed 10 bucks apiece—60 bucks a month rent—to create that little gallery. One of those people was Wally Hedrick and one of Wally Hedrick’s students on weekends at the Art Institute was a guy from the Mission named Jerry Garcia. All this stuff connects in the most obvious kind of ways, and it makes sense.

I don’t know if this is a hot take, but it feels like “Howl” isn’t given its due these days relative to the role it occupied within the zeitgeist of the time.

No, I agree. It is a very important document—that and On the Road—because it arrives at a moment when you have this void. There’s this stagnant America, and suddenly you have Allen proposing to do something a little more lively and it works.

Back to the subject of connections, Neal Cassady is a direct nexus between the Beats and hippies. He’s driving across the United States as Dean Moriarty in On the Road. Later on, he’s behind the wheel of Furthur with Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. Then he attends the Acid Tests where the bus footage is screened and The Warlocks perform. Of course, you’ve also bridged this in another manner, having written about Kerouac and then the Grateful Dead.

Jerry selected me as the biographer because On the Road was his Bible. It all added up to him, particularly when he recognized my perspective on this.

Certainly Neal was someone who appreciated Beat culture. That’s central and it just all fits together. I keep coming back to the obvious, but it’s true.

Was there someone who appears in The Last Great Dream that you were particularly thrilled to present to an audience who otherwise might not have heard about them?

Yes, Lucien Carr. He moved Jack greatly. Lucien Carr killed a man, spent time in prison and ended up working at UPI forever. He was my first major interview for the Kerouac book and he ended up sort of being a father figure to me for years after.

This stuff all connects. I introduced Lucien to Jerry at RFK Stadium and it was the only time I ever saw Jerry nervous. He was fanboying because here was one of the people who appears over and over again in Jack’s books. It was fascinating to see what Jerry’s priorities were. I introduced him to the Vice President of the United States, and he didn’t give two shits. [Laughs.] But Lucien was important to him. So that’s Jerry for you.

At one point, the book departs American shores for Swinging London. Then you return a few times to build out the story. Was that your intent from the get-go?

It seemed like there was going to be a certain emphasis on San Francisco, but my agent encouraged me to move beyond that. Of course, you can’t talk about bohemia in America without the Village, but researching is wonderful. You start poking in corners and you have no idea where you’re going or what you’re doing. Eventually, you start digging up things. LA turned out to be avant-garde painting, the weirdness of LA as a source for unusual religions and for [Aldous] Huxley and acid.

As for London, that came into focus when I realized where I was going to end the story. I thought about it for a while and figured out that I should end at Monterey Pop. I ended it there and a passage sort of sums it up: “The enduring image of Haight-Ashbury is of beautiful, beatifically high young people, flowers in their hair, listening to wonderful music while positively exuding peace and tranquility. For four days at Monterey, it was reality, and it colored the next decade and more of the youth culture.”

The more you study Monterey Pop, you can see why it could have been a disaster, but it wasn’t at all. Among other things, it presented psychedelic music to the world. That’s so ironic because psychedelic music was being presented by Lou Adler, who wouldn’t know psychedelic if bit him on the ass. But he knew that was the zeitgeist, whether or not he knew the word psychedelic.

You have it coming from San Francisco and from LA with The Byrds—although, by then, they were sort of past their sell-by date. You have it coming from New York and, finally, from London by way of Seattle, by way of Jimi and, of course, The Who. So it all comes together.

Given the scale and scope of the narrative, I imagine that various readers will take away different aspects of the story.

That’s exactly what I was after. When I was in the middle of my research and sort of brewing away, I decided that I wanted to cover the whole history of the counterculture. By then, I had a fairly decent grasp of what would be in the book, it was just a matter of putting it all together.

When did the title come to you?

Maybe halfway through, I suddenly recognized that it’s about dreams. Then one day, I was listening to “Two Djinn” and I realized that my ending was Bobby’s song.

[The lyrics quoted at the close of the final chapter are:

A short while back, the door f lung wide/

We all saw good luck on the other side/

The door blew shut, but here’s the deal/

Dreams are lies, it’s the dreaming that’s real/

Dreams are lies, it’s the dreaming that’s real/

It’s the dreaming that’s real]

I went, “OK, that fits there.” Then I called Bobby to explain that I wanted to use his song, and he said, “Sure.”

As for the title, I can’t tell you precisely when I got it but, as soon as I heard it, I knew it was the right one. For the Grateful Dead book, I had a title for years— remember, it took 20 years to write the damn book. The title was Waiting to Be Born from “Crazy Fingers”—“Something new is waiting to be born”— because every night was new.

But my father, bless him, used to say that if you have to explain a joke, then it’s a bad joke. The same is true of a lot of things— if you have to explain anything, then you’re making a mistake. I suddenly realized that late in the game, and I went, “OK, what am I going to do?” Then I said to myself: “Well, what’s the line Hunter contributed to the English language that succinctly describes the whole point of the band and their lives?” So that came at the end.

With Desolate Angel, it’s normal to select a variant on a book title for a literary biography. So that made sense.

On Highway 61 was appropriate because that ties it all together. It unites Dylan, the blues and everything. It all adds up.

The word “dream” captures the way that hippies were often portrayed in mainstream culture. They were presented as out of touch, almost to a comical degree, without much consideration as to how their ideas might have been manifested, particularly in the long term.

That is absolutely the case. There’s a sentence in there about the emphasis I placed on San Francisco because of The Diggers. I’m not saying that they were realistic, but they did some very serious thinking about non-consumption, thinking about the concept of being free.

As for the overall thesis of the book, how would you describe your theory of the case?

Once a year, I come into a high school class on the ‘60s, and I teach for a day. I try to explain to these students that it’s really quite interesting that they’re taking a class in something that happened 50 years before they were born. Clearly the so-called hippies did not achieve political power, although they did achieve cultural power. So there’s all manner of cultural influences that the hippies left behind, whether it’s food, yoga or you name it.

To this day, it’s really important, and those young people in the class take one look and they go, “Oh, yeah, right. That’s where we come from.” None of this has gone away. The idea of following a path of peace, a path of psychedelics, all of that stuff, it’s still part of our lives.