Tyler Childers and The Food Stamps: A Journey to Jubilee

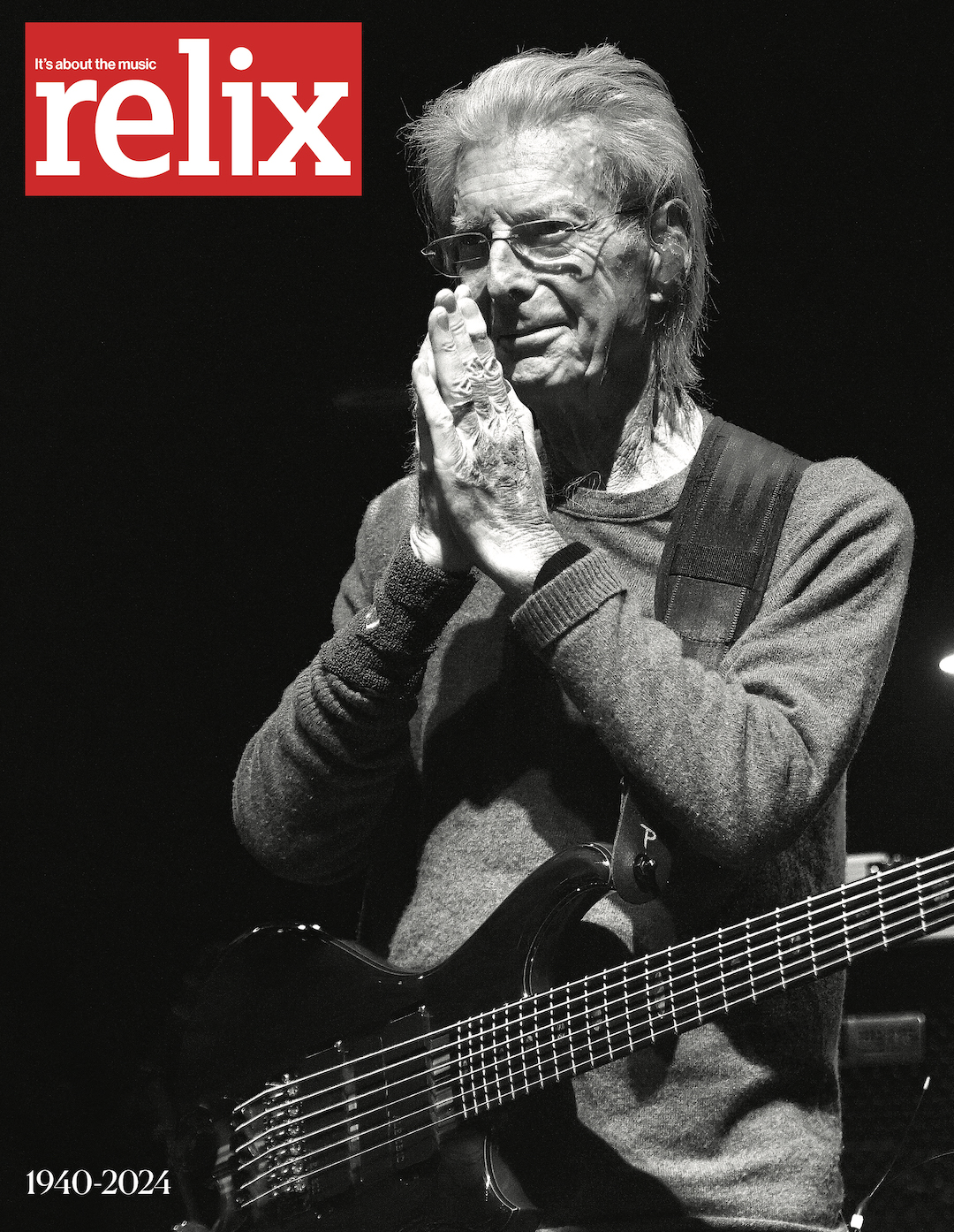

photos: Emma Delevante

***

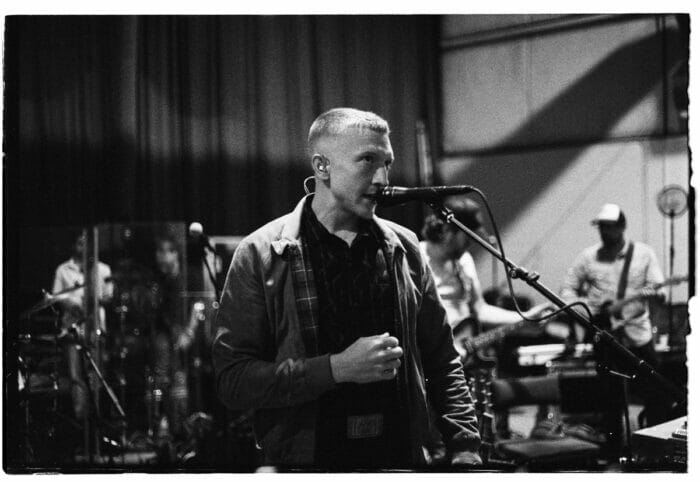

“I’m a dial-up man in a 5G world,” Tyler Childers says with a laugh after returning to a video conference with the six fellow musicians in his longtime band, The Food Stamps.

Childers had briefly disappeared from the Zoom after moving from his initial location in a nondescript room, then walking down a hallway and a stairwell before resurfacing in the rectangle occupied by bandmate Jesse Wells. The pair had driven to Nashville earlier that day to participate in the next evening’s Hello From The Hills benefit concert.

Despite Childers’ comment, he is no Luddite. His new three-record release, Can I Take My Hounds to Heaven? utilizes a variety of sonic techniques to present the same eight songs in three unique settings. The opening album, Hallelujah features Childers and The Food Stamps on their first-ever studio record after nearly a decade of live performances. Jubilee expands the palette, and the seven musicians are joined by horns, strings and even a sitar player as they reimagine the tracks. Finally, on Joyful Noise Charlie Brown Superstar (Brett Fuller) remixes the material, incorporating samples from The Andy Griffith Show, comedian Jerry Clower and portions of some church services sourced by Wells, who is the archivist at the Kentucky Center for Traditional Music at Morehead State University.

“You have the Hallelujah with just me and the boys,” Childers explains. “And then the Jubilee. So you watch that sound grow and then further warp into the Joyful Noise.”

Although the material on Can I Take My Hounds to Heaven? harkens back to Childers’ earliest days as a Baptist churchgoer, it is ecumenical in spirit. The record touches on the commonalities that unite individuals despite their personal perspectives, all of which is manifested in the song variations themselves.

This larger concept also informed Childers’ 2020 “old-time fiddle-record” Long Violent History. That album contained eight instrumentals, followed by the title track, which called for empathy in combatting racism and police brutality. Childers—who recently became a first-time father with his wife, fellow musician Senora May—has said that he attained sobriety during the process of recording Long Violent History. Proceeds supported the Hickman Holler Appalachian Relief Fund, a charity Childers created with May to aid philanthropic efforts in the region.

Indeed, even as Childers attains global renown, he remains conscious of giving back to his local community. The Hello From The Hills show raised funds for the John Prine family’s Hello In There Foundation along with Hope in the Hills, which Childers co-founded in an effort to address opioid addiction in his home region. In mid-December, Tyler Childers and The Food Stamps appeared at Christmas Jam, which has long provided assistance to Warren Haynes’ hometown of Asheville, N.C.

Childers notes, “Warren has been doing that for 30 years and I definitely appreciate and admire it. I hope to continue to do things like that because we wouldn’t be who we are if it wasn’t for the people and the places that shaped us. Growing up in the church with the idea of tithing and offering 10% to your community is a big deal.”

Just as the songs on Can I Take My Hounds to Heaven? developed over the course of three iterations, so too has Childers’ Appalachian-based group evolved over the years. In 2011, the Paintsville, Ky., native released his self-financed Bibles and Bottles album, and after expanding his ambit into Huntington, W.Va., he debuted at Shoop’s, opening for local trio Deadbeats and Barkers. Those three musicians would come to join Childers as The Food Stamps: James Barker (pedal steel), Craig Burletic (bass) and Rodney Elkins (drums). Wells followed in 2017, lending fiddle, banjo and acoustic guitar following the release of Childers’ breakthrough album, Purgatory, which was produced by Sturgill Simpson and David “Ferg” Ferguson, and featured some Nashville studio all-stars. Keyboardist Chase Lewis entered the fold two years later after Simpson and Ferguson returned for the follow-up, Country Squire, enlisting some of the same players. Finally, acoustic guitarist CJ Cain, from “rhythm and bluegrass” quartet The Wooks—of which Wells also is an alum— completed the current lineup when he came on board in the summer of 2022.

The septet—who last performed together a few weeks earlier at Christmas Jam—maintain a lively, affectionate patter throughout the Zoom conversation. Since the pandemic, they have only performed intermittently and clearly welcome the fellowship that they have forged over time, spending up to 250 days a year on the road together. Their fans share this sentiment—every date on the upcoming Tyler Childers and The Food Stamps tour, from April through September, is already sold out.

To get things rolling, can each of you talk about the first album that resonated with you when you were growing up?

CRAIG BURLETIC: The one that made the first impact on me was the Nirvana live CD, From the Muddy Banks of the Wishkah. My brother had that one and he handed it down to me.

JAMES BARKER: I shared a room with my older brother growing up, so there was already a pretty good selection of alternative rock stuff. But the first record I bought with my own money was the first Foo Fighters record with the ray gun on the cover, and I still have it.

CJ CAIN: When I was a kid, my dad was really into Steve Earle. The album Guitar Town was the first music I remember being attached to at age 3 or 4. I had a little red plastic guitar, and I would set the plunger up as a mic stand.

TYLER CHILDERS: Ricky Skaggs was a hometown hero and I remember carrying around one of his cassettes when I was five years old. My first concert was seeing him real close to home when I was 5. So Ricky Skaggs made a big impact on me. I didn’t do the plunger microphone stand, but I did do the coat-rack guitar, which was a really big guitar. I jumped around on my bed with that coat rack playing guitar to CCR.

CHASE LEWIS: My parents owned a Christian bookstore, so we had lots of free demo CDs from Southern gospel groups. I can remember putting on headphones and learning all the songs to the Gaither Vocal Band. I used to steal all their piano player’s licks. [Laughs.]

JESSE WELLS: Mine was John Hartford’s Aereo-Plain. My parents had it on a reelto-reel player and that was one of the first records my mother listened to when I was in the womb. So it’s been with me my whole life. Tyler and I were talking about it on the drive down today.

RODNEY ELKINS: Mine was probably Billy Joe Shaver’s Live at Smith’s Olde Bar. I had it on tape and then I wore it out. My dad had it on CD, so I stole it from him but I also wore that out. It doesn’t play anymore but I still have it, though.

Tyler, did the vision for the new album come to you in one fell swoop or did the idea develop over time?

TYLER: It definitely developed over time. As far as the three installments go, I looked at it as an opportunity to experiment with production and how that can affect the songs individually. I was thinking of my personal experiences recording in a studio. I had my first go-around in a studio when I was 17, getting ready to turn 18, and I did Bottles and Bibles.

I’d saved up 500 bucks. I knew a guy that had a studio in Paintsville, and I had a dear friend—an old high school teacher— that agreed to come and accompany me on acoustic. Then I paid John Rigsby $75 to come play fiddle on two songs. It sounds the way it does because that’s all I could afford.

Then there was Red Barn One and Two, which were live. On one of those I was playing with a bluegrass band and on the other one I was playing acoustic. That was how I was playing live at those times. Red Barn was kind enough to allow me to have four tracks off each of those performances. So that’s how people perceived my sound—because it’s what I packaged and was selling.

Then I ran into Sturgill and got with Thirty Tigers. So I was able to go into Ferg’s studio with these amazing musicians and really flesh out this sound [on Purgatory], which was different for listeners who had heard Bottles and Bibles and these very stripped-down things. Then I did it again on Country Squire.

This time, it was an experiment on further fleshing those things out—“What happens if you are able to experiment with every whim that you have in your head.”

When you’re writing songs, do you typically write for the live show or for the record?

TYLER: I write for my health. [Laughs.] I also try to write for the band. My songwriting changed a lot when I started playing with these guys. Before, it was more like a young dude with an acoustic guitar, playing kind of singer-songwriter-y. Then once I got with the boys, it changed the songs I was writing. So I write with the band and the live performance in mind and then, hopefully, they make it to a record eventually.

As you were thinking about this album, did the versions of the songs on Hallelujah always appear first in your head? Did any of them take on a new meaning for you after altering the arrangements?

TYLER: The different installments of the album add different textures. I think what justifies the importance of both of them living together in the same place is the ability to hear what those different textures can do for the song. “Heart You Been Tendin’,” with just the band, is this heavy hitting, rocking thing but it feels so much deeper and intense with those strings backing James’ solo into the rock ether. But on a certain day, that’s not necessarily where you need to go so you’ve got the band one.

The version of “Jubilee” that appears on Hallelujah is an instrumental, while the song’s traditional lyrics are added for the version on Jubilee. What led you to approach it that way?

TYLER: The way that it is on Hallelujah is the way it is if we only have members of the band playing. I heard a woman singing that, and I heard Luna specifically. But, because she wasn’t in the band, I put her on the Jubilee part, along with the sitar and the dulcimers. It was really cool to have the dulcimer and the sound of the sitar and then those two things playing off of each other within that song.

CRAIG: I didn’t know there was gonna be vocals on that song or on “Two Coats” when we recorded them. It can be a challenge to make a fiddle tune sound funky and not sound hokey. So it took a little bit of planning to make an arc in that tune with nothing else going on. Then when I heard the Jubilee version with Luna singing on it, it was this really beautiful moment for me.

Can you talk about the new version of “Purgatory” and how that came together?

CRAIG: When we were doing this session, that was one of the first ones Tyler brought up. He asked us if we thought we could do it funky. We thought we could, so we messed around with it and eventually came up with the themes that you hear. I think the original “Purgatory” is such a perfect recording that we needed to have that direction to do it funky and change it up.

TYLER: I wanted to make a version that was ours. The Purgatory version of “Purgatory” was very specific to the band that got together that day and made that album. I’ve always felt like it didn’t translate well. It just wasn’t us. That particular recording relies heavily on a lot of banjo and a lot of fiddle and the way that those two instruments play off each other. We have both of those instruments in our band, but we have one person playing both of them. He’s good, but he can’t play both of them at the same time. So I was like, “If we totally scrap that, what would be the Tyler Childers and The Food Stamps-sounding ‘Purgatory?’” The best way to do that was to give it to the boys and tell ‘em to ride it like they stole it.

That calls to mind the development of the band. Let’s walk through it, starting from the very first night when Tyler opened for Deadbeats and Barkers. What do the three of you remember of that first evening and what did you hear in Tyler’s music that drew you to it?

RODNEY: We were at Shoop’s [in Huntington, W.Va.]. He played solo and we played later. The way he played and sang—and the great songs that he had—just shut the whole room up. His songs were so much fun to listen to and they were so beautiful. They made you feel something. We wanted to lend whatever we could to help make those amazing songs just a little bit better. Anybody seeing Tyler in those days could tell he was going to be going somewhere. So if he was gracious enough to take us with him, we were definitely along for the ride.

CRAIG: We were a trio that did a mixed bag of music. We did rock, country and funk songs. In Deadbeats and Barkers, each of us sang the songs that we wrote and we passed the mic around. Sometimes all three of us would sing lead on the same song. We were writing our own music, but we also idolized The Band. So I think, in some ways, we were ready to find a Bob Dylan.

Tyler, what did you hear in Deadbeats and Barkers that made you think they would be a good match for your songs?

TYLER: My first paid gig in Huntington was at Shoop’s, opening for them. It was my first time meeting the boys. After getting to know them and hearing their rock band, I was really excited to play music with them. They allowed me to put more punch and grit behind the songs.

Ever since high school, I’ve listened to a lot of Drive-By Truckers and Chris Stapleton-era SteelDrivers with these rocking, visceral vocals. I wanted to bring that sound into what I was doing. So getting with these boys allowed me to do that.

They were good dudes for the job because they were all great at their instruments, but all three of them also were songwriters and played with a songwriter’s mentality. A lot of times, drummers will just come in, and they will be like, “I’m just going to play the shit out of these things.” But Rod would look at the lyrics and think about what the song was trying to convey, which would shape what he did on something. I also remember, very specifically, Craig asking me, “So this verse is kind of talking about reincarnation, but it also seems like it’s talking about the band being on the road, right?” Plenty of other musicians would only care about what key it was in and the chord changes. But he wanted the lyrics to inform what he was doing.

Jesse, you joined a few years later. What drew you in and what were your initial thoughts on the band and the material?

JESSE: I’d played with Tyler during the Red Barn days some, so I knew his prowess as a songwriter and a performer. Then, one night in Denver, CJ and I sat in. I had a fun night and got to know Craig, Rod and James a little better.

RODNEY: It was right around the time that Purgatory came out.

TYLER: Purgatory was really heavy on fiddle. I was like, “Man, we need to find a fiddle player.” Then it occurred to me: “I used to play with Jesse in a bluegrass band and Jesse’s been playing some of these songs longer than the band’s been playing these songs.”

Let’s jump ahead for a moment to Joyful Noise. Jesse, you played a major role in sourcing some of the material through your role as an archivist at the Kentucky Center for Traditional Music. How did you approach that?

JESSE: Tyler was looking for certain church services and certain textures to add. I had a great repository at Morehead State University to draw from. Fortunately, we had some recordings from nearby where Tyler and I both grew up and we sourced those. I brought many hours worth of material to Tyler for him to sift through. Then he chose what he liked and shared that with Brett, so it worked out rather well.

Tyler, what led you include snippets of The Andy Griffith Show in this portion of the record?

TYLER: That goes back to the three installments—experimenting with production and how much you can add to something and what that does to change it. I felt like we were all standing around cooking down syrup, cooking down sorghum, where you keep on adding the heat to it until it gets thicker and thicker. That was what Joyful Noise was. But it was also this abstract combination of intangible influences.

Andy Griffith is one of those influences. If we were going to go back to the three cassette tapes that I had as a kid, I had Ricky Skaggs and then some Jerry Clower tapes. So the Southern humorist was as much of an influence on me as any musicians that I was listening to.

Andy Griffith was one of those Southern humorists. The two scenes in Andy Griffith that always stuck with me were the Paul Revere story when he is telling the kids “the British are coming,” and his explanation of Romeo and Juliet. I really wanted to put that within the context of this music.

Resuming the chronology, Chase, can you talk about your connection with Tyler and the band?

CHASE: At the time, I was working exclusively on cruise ships. I don’t know if you know much about the cruise ship world, but when you’re out there, you don’t really even know who the president is because you’re so detached from the U.S. But I was home for vacation in between contracts and I posted something on Facebook like, “Hey, I’m back home for a couple weeks. I’d love to get together with some guys and play, if anybody needs a piano player.”

Then Jesse messaged me and he said, “Hey, I saw your post. We just had a new album come out and we need a piano player.” I was like, “Oh, you mean for a weekend?” He was like, “No, we’re pretty much gonna give you this gig if you want it.” That was a lot to take in. [Laughs.]

TYLER: I’d met Chase in Prestonsburg, Ky., when I was like 15 and he’d made an impression on me. I always kind of kept up with him because he was one of the baddest piano players I knew of from back home. Country Squire had a lot of important piano parts, and I asked Jesse: “When’s the last time you talked to Chase Lewis?” He was like, “I think he’s on cruise ships.” It turned out that he was looking to come off the boat, and we were looking for a piano player.

CJ, that finally leads us to you. You were the last man in. What did you think that you could bring to bear?

CJ: I definitely was the last guy in, but I’ve been around these guys for a long time. It’s been cool to watch them grow into Tyler’s music and also bring their identity to it.

Tyler’s songwriting is the most important thing. On some of these newer songs, I feel like he’s really getting after it vocally, but it might be uncomfortable to play an acoustic guitar and sing the way he’s singing.

The Wooks were on hiatus and I was staring down the barrel of potentially getting a desk job or something awful like that when Tyler called.

Tyler and The Wooks had performed together and we’ve all been around each other. Jesse was in The Wooks, so the only person that I felt like I had to prove myself to was Chase. I figured out that, as long as I laughed at his jokes, I’d be OK.

TYLER: With this new album, I was focusing a lot more on the singing aspect of what I do. So I wanted to focus less on holding down the acoustic guitar. But if I’m not playing it live, then that sound is sonically missing. So I was thinking of who I would want to be on the road with—stuck in a fart tube driving 75 miles an hour—who also plays acoustic and is a great hang. And I was like, “CJ freaking Cain!” So here we all are. When I was little, I always wanted to live in an apartment with six of my best buddies and that’s kind of what I do.

CJ: A really tiny apartment.

TYLER: That you can’t shit in.

CJ: So depressing. [General laughter.]

Jumping back to the record, Tyler, can you talk about how “Way of the Triune God” originated?

TYLER: I was listening to old Alan Lomax recordings and a lot of my favorite ones were the ones that like Bessie Jones was singing on, like “Turtle Dove.” I’ll get really stuck on a song, and I’ll listen to it on repeat for hours and hours a day. That was one of those and I was thinking, “If I was to write a song to pitch to Bessie Jones, what would it sound like?” So I wrote the song with that in mind, as if I was pitching it to her. It lived as an a cappella voice memo on my phone for a long time. Then, when we were getting together to work on this album, I said, “I think this would be in F. Let’s just go with that and see what happens.”

Bessie Jones felt it was her mission to preserve the cultural heritage of her forbears. Do you feel a similar charge to present the music of your home region or is all of that incidental to creating great songs?

TYLER: I do feel there is a responsibility, although right out of the gate I don’t know how much of it was incidental and how much of it was intentional. First and foremost, I wanted to present myself and my art, which is a product of a culture and an area and all of that. But, now that we’ve been given a platform and an audience, there is a responsibility that comes with that to help preserve where we came from and influenced where we’re going.

I don’t necessarily feel a responsibility to be an archivist like Jesse, but if I can shine a light on things that have influenced me from my area, then I definitely want to do that.

You recorded the album in Kentucky and West Virginia. To what extent do you think those locations have a presence on the album?

TYLER: It’s got this gritty sound to it like the music scene that we cut our teeth in. We recorded in Huntington where we grew up as a band and a lot of the boys literally grew up. It’s where we met and where we practice. Also, some of the reverb on the album is from a sinkhole in Kentucky, so it’s an organic reverberation of the place where we’re from, creating the sound that you hear. James, it was recorded at your place. What do you think?

JAMES: Along with what Tyler just said, it’s comfortable to be at home. It’s also where we rehearse a lot of the time. We don’t have much more to think about other than getting the job done, which is different from when we’re on the road. So we can get straight to work and not have to worry about easing in so much.

Earlier, you all spoke about formative albums. Can you talk about impactful live shows?

CRAIG: Going to live music performances wasn’t a thing my family did, so I didn’t go to anything until I was like maybe 12 or 13. Then I went with my friends to X-Fest. I was in a mosh pit and I got destroyed—these combat boots came flying down and hit me in the head. But I thought, “This looks cool. I want to do that.”

TYLER: I always wanted to go to X-Fest.

CRAIG: I went to like three or four of them. I saw Nickelback do a Rage Against the Machine cover. They did “Bulls on Parade” and the lead singer in Nickelback was wearing a cowboy hat and playing Rage Against the Machine. It was pretty wild.

TYLER: You were the coolest kid in middle school, man.

RODNEY: For me, it was Marty Stuart at Buckle Up when we got to see him after we played that music fest. It was kind of raining and they came out in purple suits, didn’t say a word and started playing “Stop the World (and Let Me Off ).” It just kicked me in the chest and I looked over at James and Craig and was like, “I’m doing this forever.” [Laughs.]

CHASE: I couldn’t tell you the first concert that influenced me. I wasn’t a concert-going kind of kid and I’m still not. I saw Taylor Swift open up for Brad Paisley, although that didn’t influence me as an artist.

TYLER: I thought you were gonna say X-Fest.

CHASE: I wish I had something cooler to say, like Alice Cooper as a 10 years old or something. I did see Elton John recently and that revived my love for music and what it can be.

CJ: I grew up in two different musical worlds. My mom was into country music so I saw a lot of Travis Tritt and Vince Gill shows. My dad was into the Grateful Dead, and he got into bluegrass through that. But as far as an influential concert, that didn’t happen until Tony Rice came to the Kentucky Theatre around 2000, after I got a Tony Rice CD called Tony Rice Plays and Sings Bluegrass. Peter Rowan played with him and J.D. Crowe sat in. I thought, “I want to be like this guy.” Also, Guy Clark opened and he later became one of my biggest songwriting influences.

JAMES: My dad took me to see Rush when I was 9 or 10. That was pretty huge in all aspects. I also had a really good Bonnaroo one year, running around to see the Allman Brothers, Herbie Hancock and the Headhunters, and Modest Mouse [in 2005]. That was a pretty good trifecta.

JESSE: For me, it was growing up seeing my family play—my dad and my uncles. There was lots of live music all the time.

TYLER: Jesse has played with like every Kentucky legend that you could think of at some point or another. He has been the formative show for a lot of people.

Tyler, when CJ mentioned the Grateful Dead, it reminded me of your performance with Bob Weir at the Ace anniversary shows last year, which now appear on a new album. To what extent did you listen to the Dead growing up?

TYLER: I had an older cousin who helped encourage my love for music. She came from Indiana to take me to see Bob Dylan when I was younger, and she followed the Dead around when Jerry was still alive. She introduced me to the Dead when I was a young ‘un, and I listened to a lot of the Dead and read The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test when I was like 14. Then all of a sudden, I ended up meeting Bob Weir and now our movies are connected. It was a long, strange trip kind of moment. It was super cool.

What led you to pick “Greatest Story Ever Told?”

TYLER: They reached out and asked me if I wanted to be part of that evening and told me that they were going to play the album top to tail. Then they asked me to pick one or a few songs that I wanted to sing on. So I sat down with Ace, heard that big war whoop on “Greatest Story” and I could see myself having fun singing that song. Then I was like, “Slow down, and keep listening. That’s just the first song.” But, in the end, that’s the one I wanted to sing.

When I last spoke with Bob for Relix about performing his songs, he said, “The more able I am physically, the more those characters have to work with when they step through me.” Do you echo that approach in any way?

TYLER: That’s pretty awesome. We’re vessels for the spirit. So keeping your head right and keeping yourself fit is allowing yourself to become more in tune and able to receive that spirit. I definitely feel that since getting sober and trying to live healthier. I feel more aware and less numb to my surroundings. It definitely helps my performance.

Plenty of people cover your music. Is there an interpretation that led you think about one of your songs in a new way?

TYLER: I’m really excited about Elle King’s cover of “Jersey Giant.” That really made me appreciate that song and fall in love with it again. I wrote it when I was 19, and I wore it out, personally, within two years. I hadn’t played it since I was 21 or 22. I kind of forgot about it. Then somebody found an old SoundCloud recording of it and it got TikTok trendy or whatever.

So RCA contacted us because Spotify had reached out and said, “People are messaging us on our socials asking for Tyler to put out a ‘Jersey Giant’ recording.” I was like, “No, if I was gonna do that, I’d have done it in the last nine, 10 years.” I just don’t connect with it anymore.

Then I remembered meeting Elle in Ohio a few years back and thinking that she was really cool. I had been following what she was doing. So through the RCA connection, I was like, “Do you think that Elle would want it?” They reached out to her for me, then we spoke about it and she was totally down to do it.

When she came back with her recording of the song, the way that she performed it and treated it gave me a new appreciation for it.

Back to “Greatest Story” for a moment. You’ve continued to perform that song, including a memorable version with the McCourys.

TYLER: It’s up there in my register, and if I could get away with singing it every day, then I would sing it with everybody all the time. But I’ve realized that it is one of those special occasion ones where I’ve really got to be feeling it and I am in tip-top shape. The vessel has to be fully prepared for that one.

I saw one performance where you seemed to be downing some honey before you went into it.

TYLER: Somebody once told me that they saw Mars Volta chugging honey and I was like, “That’s ridiculous.” Then we were on the road, back before COVID, and I was drinking a lot. We were all living pretty unhealthy and we were on the road 250 days out of the year. This one day, I didn’t feel like being at the show, but it was go time and there was always honey for tea. So I was like, “Screw it. I’ll take that onstage and chug it.” And it helped. It probably wouldn’t be advised by vocal therapists or professional singing teachers, but neither would eating a whole pizza and pounding a six pack before you go on the stage. I don’t know—cirrhosis, diabetes . . . we all gotta go some way.

Do you have a formative show, by the way?

TYLER: Well, I did get to meet Ricky Skaggs when I was 5 years old. He told me to never quit playing and I definitely didn’t. But I think a really big one was when my dad took me to Prestonsburg to see John Prine when I was 14. Just watching him on stage really stuck with me—like, “If I keep on writing my songs, maybe one day I can do this for a living.” Then I ended up opening up for him and eventually going to Australia with him.

I can’t imagine engaging with his music at 14. I’m still wrapping my head around some of his songs now.

TYLER: I feel like John Prine wrote songs that you could grow up with. You could be a kid, and if you’re not emotionally mature enough for everything, they’re still fun songs. Of course, you’ve also got your heavy hitters that might go over your head. I listened to “Sam Stone” but I didn’t appreciate it until that moment seeing it live. I remember getting chills up and down my spine after he told a story about Sam Stone and then played it. But there are also songs like “Please Don’t Bury Me” or “Fish and Whistle.”

As you grow up and you experience heartbreak, loss and fear on a very deep level for yourself, your family and the state of the world, there are also songs in that catalog that are ready when you get there.

Tyler Childers and The Food Stamps have only played a limited number of shows since the pandemic. Your major touring will finally resume later this year. Do you think that music in general, or live music in particular, means something different to people these days?

RODNEY: It’s more important now than ever. There was a good long time there where you couldn’t go see anything and, quite frankly, it sucked. I know my world was a little unhappy because of it. I listened to more records but if people couldn’t get together and make said records, then that was a problem, especially with the state of the world. People have got to let those feelings out and put something out there that makes people feel things.

CRAIG: Before we got together and did the Hounds record, we had played “Old Country Church” for years. But this was our first time seeing each other in six or seven months after previously seeing each other however many days a year for years. Then hearing Tyler sing the line that says, “With my friends in the old country church” with such conviction, made me realize that the old country church was James’ studio, and I was back with my friends. Then when we had our first show back, we opened up with that song and it had an impact on me because there we were, back with a Tyler audience.

TYLER: I don’t think that the nature of live music and performing has changed so much, but maybe COVID led to a reevaluation of what it meant for people individually. A lot of us took it for granted, and once we did get to play again, it gave us a greater appreciation for it. The importance of the live show is fellowship. It’s our church and that’s what it is for a lot of people. That’s what live music should be in a sense— a communal gathering.

JAMES: I think it’s important to have a diverse a group of people in the room. That’s especially true these days with social media and people surrounding themselves with other people who have the exact same thoughts and are just reinforcing those thoughts. I want people who have never heard of Tyler Childers to come to these shows, just like I want to go to shows that aren’t in my comfort zone and be around people who aren’t in my comfort zone.

TYLER: I want to sing songs about reincarnation and psychedelic drugs to hard-shell Baptists.