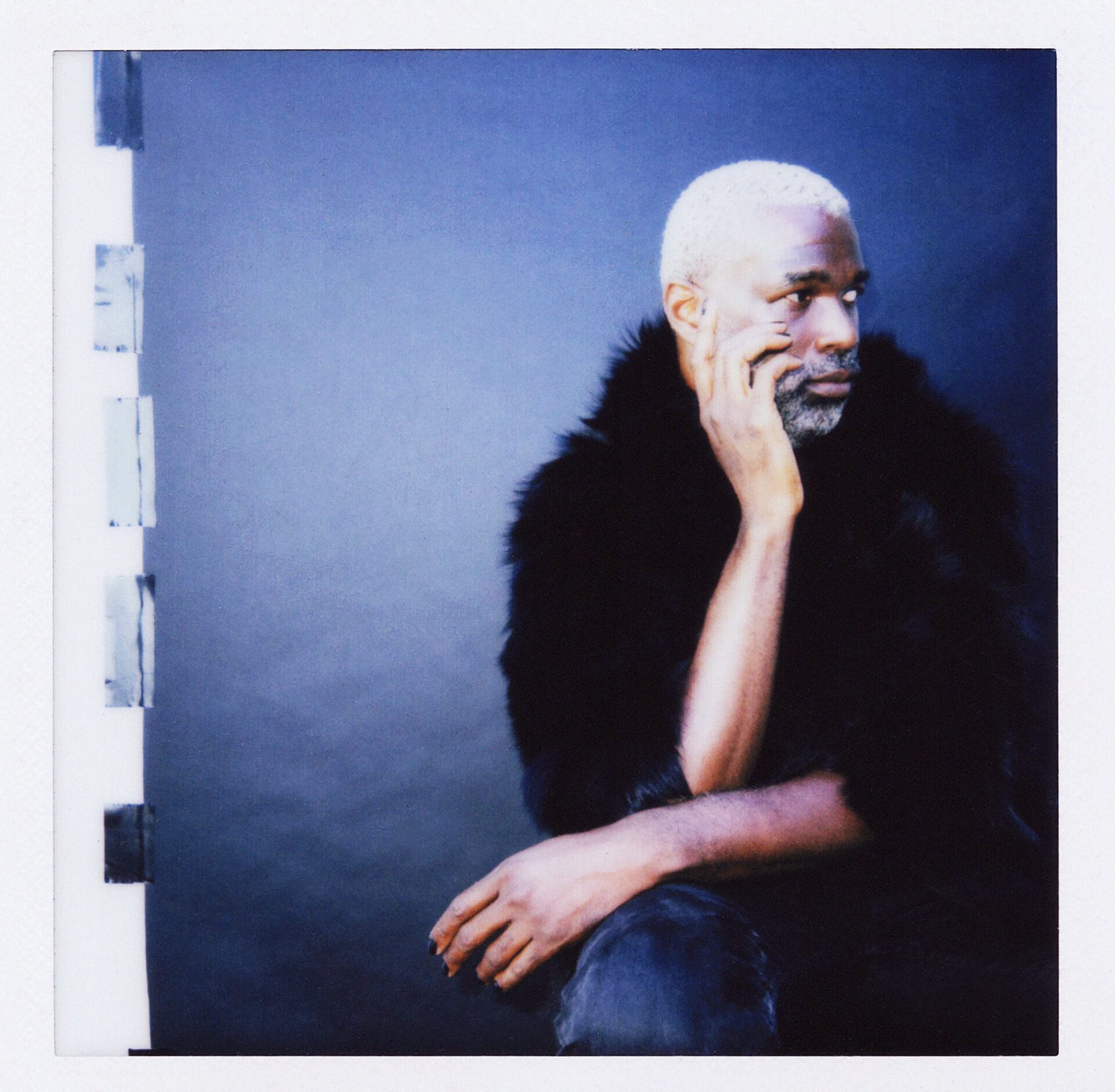

Tunde Adebimpe: Depth of Field

Photo: Xaviera Simmons

***

On stage with TV On The Radio, the art-rock kings of 2000s Brooklyn, Tunde Adebimpe was known to make a ruckus—an often-intense, cathartic ruckus pulled from deep, dark places. Maybe the most famous example, from 2006, is the band’s transcendent Late Show performance of “Wolf Like Me,” a distorted barnburner that finds the singer howling, “Got a curse I cannot lift/ Shines when the sunset shifts.”

Adebimpe’s colorful solo debut, Thee Black Boltz, features no such primal outpour, favoring the brighter, more graceful flavors from his band’s five acclaimed LPs. The project was catalyzed by similar angst—in this case, the unexpected death of his younger sister, extreme social unrest in the United States and the general uncertainty of post-pandemic life. But this time, instead of funneling those feelings back out into the world, he’s countered them with escapist warmth.

“When I was younger, there were some TV on the Radio songs where it’s like, ‘I’m really not in a good place, and I’m going to express that on these songs,’” he says. “There’s more of an anger than an antidote in some of them. For me, that was a product of—I don’t know if it’s not having the tools or just not being receptive to pulling myself out of that place. The [solution] was, ‘I’m going to transfer all of these horrible feelings to, for lack of a better metaphor, this painting, so that when people come here, they’re gonna know.’

“I sympathize with a lot of very sad music, very angry music,” he continues. “It definitely works and has a place, but I feel like there are two forms of it. When greater tragedy comes into your life, there are moments where you’re like, ‘I don’t actually want to be in that place at all.’”

The nice thing about touring all these heavy TV on the Radio songs, he says, is that the repetition transforms them. It’s impossible to be in that same emotional space hundreds of times. Ruminating there, he recalls playing a transformative bill with the dreamy alt-rock band Blonde Redhead.

“It was when we first started out, probably 2005 or something, and we were supposed to open for them,” Adebimpe says. “We were actually late, so we had to play after them. Right before they went on, I was like, ‘This band has written some of the most heartbreaking [songs]. You sympathize with this very down place they’re in. How are you gonna do that? What place do you have to get in? What’s it gonna be like in the room?’ But when I watched it, they were clearly having a very good time playing, and the way they brought this much to people, it was like a scale model of those feelings, as people who’d stepped away from those feelings so that they can present them. It was lightly theatrical, which was beautiful—and a real lesson to be like, ‘We don’t have to be basement hardcore and get exhausted after every show.’”

Adebimpe applied those lessons during the joyful creation of Thee Black Boltz, which was co-written and co-produced with a crew of key collaborators. This sense of creative community has always been crucial to Adebimpe, who split his childhood between Pittsburgh and his parents’ original home of Nigeria. When he moved to New York for college, he fell in with some fellow visual artists and aspiring indie-rockers—sharing an apartment with Antibalas founder Martín Perna and Daptone visionary/Dap-Kings bassist Gabe Roth for a time—attending NYU Film School and initially pursuing a career in stop-motion animation. (He wound up working on the bizarre and darkly comedic MTV show Celebrity Deathmatch.) Adebimpe, an obvious polymath, ventured into acting—a passion that’s bloomed even further in recent years, particularly after TV on the Radio slowed their pace in the mid-2010s. And he also started experimenting with bedroom four-track recording, which led to meeting producer Dave Sitek and forming the band we all know and love.

Thee Black Boltz, naturally, marked a shift in his process, as he worked closely with Wilder Zoby, best known for his work with hip-hop duo Run the Jewels. The producer had known Adebimpe since roughly 1999, back when the former’s band Chin Chin played shows with early incarnations of TV on the Radio. Zoby, a Louisville, Ky. native, grew up knowing multi-instrumentalist Jaleel Bunton, and the friendship circles overlapped once the latter joined TV on the Radio. Despite having known Adebimpe for two decades, Zoby had never worked with him, until they were united by an unlikely gig—scoring the animated PBS Kids show City Island.

“He did the first season all himself except for the final episode, which was pretty much all music and maybe felt like a little heavy lifting for him,” Zoby says. “He called me up and said, ‘Can I come over to your place, and we can work on this episode together?’”

“The workload was kind of heavy,” Adebimpe admits. “It was a real factory style thing, so I just called Wilder in to help out with instrumentation and mixing and stuff. We just realized we were both around. While we were doing that, I had two demos going, and I was thinking about producers, and I said, ‘If you’re bored and want to give these a try…’ He was like, ‘Oh, I’d love to.’”

“That was when I had a back house that I was able to use as a studio,” Zoby adds. “He came over and we did this one episode, and it went really well. About four months later, he hit me up and said, ‘Hey, I have a record deal. I had so much fun working on that thing with you. Why don’t we make this record together?’”

***

However, despite his impressive résumé, it wasn’t exactly easy for Adebimpe to land a record deal. In fact, despite his status as indie-rock royalty, he had a hard time finding any takers at first.

“It was definitely a weird feeling [that no one wanted it],” he says with a smile. “I started making these demos in 2019 or finding stuff that I thought [I might use]— I didn’t know if it would be a record, just something. When I finally got it together, it was a little bit after the pandemic had started. Everyone was figuring out what was going on, and I started shopping them around. There were two things where it was a wholesale rejection. It was a combination of things. People said, ‘These are cool, but it doesn’t seem like it’s for us,’ and they also said, ‘We don’t know what’s going to happen with the pandemic, and we don’t know if people are going to tour and if we can take risks on new things.’ It was a combination of practical and aesthetic things. Looking back on it, knowing a bit of the pandemic stuff made it a little easier to take, but I certainly had a moment where I was like, ‘It’s not 2008, and it’s not the band. It’s just me, and perhaps no one gives a fuck.’” [Laughs.]

But Adebimpe certainly did, sending a mountain of ideas at Zoby—from skeletal demos (mostly with drum machines, vocals, and bits of synth or guitar) to random fragments he threw into a folder named “Bits and Bobs.” Zoby was immediately excited: “He was like, ‘I trust you. Do your thing with these.’” But Adebimpe’s busy schedule did initially give the producer pause. “I knew he was working a bunch as an actor. And, not too previous to that, I was working on a project that ended up getting deaded,” Zoby says about Adebimpe, who has turned in well-received performances in films and television series like Spider Man: Homecoming, Marriage Story, Star Wars: Skeleton Crew, Strange Planet and Rachel Getting Married. “When he first [asked me to work] on his record, I said, ‘Absolutely, no question. Whatever you need, you got it.’ Then maybe about two weeks later, I called him and said, ‘Before we get too deep, I’m a little worried we’re gonna work on this for a few months and make a bunch of progress, and then you’re gonna get called to make a movie somewhere and your life goes on a different path. What level of commitment is this?’ He said, ‘I’ve told my agent I’m only open to things in [Los Angeles].’ He called me a week later and said, ‘I swear to God, you had a premonition: I have to go to Oklahoma for three months for Twisters.’ [Laughs.]”

Ultimately, it was a blessing in disguise: Zoby wound up working on the tracks by himself for around three months, establishing some “ground-level” elements that Adebimpe could expand on once he returned to the studio. (The duo now share a space in Los Angeles.) Their end result had a “mixtape” feel, the singer says.

Mixtape is a fitting description of Thee Black Boltz: Some tracks, like the tense, synth-pulse post-punk of “Magnetic,” call to mind Adebimpe’s classic work with TV on the Radio; other moments might surprise people, like the sparsely fingerpicked love song “ILY” or the collage-like “Pinstack,” highlighted by dusty Motown-style drums, choral vocals and a wonky Frankenstein’s monster of a guitar solo. “There are so many types of music that Wilder and I love and mess with,” Adebimpe says. “It was a real joy to be like, ‘We can actually put this ridiculous fuck-off guitar solo in the middle of this absurd song about reincarnation.’ It was nice to have that open road to do it. I don’t want the words ‘too much’ to be anywhere near [this record]. We should push it as far as possible.”

Another example of the album’s chaotic joy—centerpiece “The Most,” an air conditioned blast of stammering synth lines and radiant chorus hooks. It actually began its life, many years ago, as a demo Adebimpe wrote somewhere between 2011’s Nine Types of Light and 2014’s Seeds.

“I remember playing it for the band,” he says. “And they were like, ‘Eh,’ and that was fine! Back in the file. [Laughs.] You get to that point where you’re like, ‘Nobody else likes this? I really like it, and that’s enough.’ I took it to Wilder, and he was immediately like, ‘Yes, let’s do something with this.’ It’s one of a couple songs on the record about some kind of breakup, and the ultimate sentiment is that, however things went down with this person, we taught each other something about love or affection. It’s like, ‘I can’t waste my precious time hating on you’—you just can’t. There was always this kind of rocksteady lilt to it, so I feel like we pushed that. There’s this beat that’s in a lot of older dancehall songs called the ‘Sleng Teng’ beat. This was during the pandemic, and I was nerding out while going through everything. It’s just a setting on this certain Casio. We got that keyboard, which is good for a lot of things, but we put it in there in the middle as an Easter egg for DJs or fans of dancehall or old rocksteady.”

***

None of this experimentation will shock TV on the Radio fans—few albums are more sonically exciting than Return to Cookie Mountain or Dear Science. But working without the safety net of his longtime bandmates—with the exception of Bunton, who contributed to two songs— pushed Adebimpe to gently adapt his process, and you can hear that evolution. “With the TV on the Radio stuff, after a while, you kind of figure out, ‘If I do three quarters of this, I know Kyp [Malone] is going to take care of this section,’” he says. “Whatever he does, I feel like it will totally work and we can talk about that. Dave will have his hand on all of this stuff.’ It was just knowing who to tag in and how, which became sort of second nature after a while. This time, it was just super bare-bones in terms of the structure and what could go where. I had to kind of not think that way, and I actually didn’t want to think that way.”

However, that’s not to say Adebimpe has any clue what Thee Black Boltz even sounds like—or that he’s ever been able to describe his early music. “This might sound very strange, and maybe it’s because of how we do it or because I’m inside it, but I have no predictive thing about what a TV on the Radio record should sound like,” he says, before turning his thoughts to the handful of dates the group has turned in since reemerging from a five-year performance hiatus this past fall. “I guess I could step away and get an overview, but I’ve actually never listened. I had to do it because we’re going back for these small reunion shows, but I’d never listened to a whole record of ours outside of, ‘OK, it’s been mastered. Let’s sit there and give it a listen.’ You’re like, ‘Maybe in 10 years, I’ll be able to do it.’ With these, it was just sketches that I wanted to flesh out, and it was kind of like, ‘I’m just gonna do whatever and see what sticks.’

“The thing I did do consciously,” he adds, “is that if I felt uncomfortable about something being in there, most of the time, I would not get precious about it. I’d be like, ‘That’s great. I want to feel out of my depth with a couple of these things.’ There were things where both Wilder and I were like, ‘I don’t know if this works. I don’t think it doesn’t work, but I don’t know if it works, and that’s a circuit for someone else to complete.’ In a lot of ways, after you’re done with something, it’s none of your business what anyone thinks about it. Fugazi did not care what I thought about their record. They weren’t like, ‘What’s this kid in Pittsburgh think about it?’ It was also this David Bowie thing of, ‘Your feet should never be touching the bottom of the pool.’ You should always be a little like, ‘I don’t know,’ because that keeps you interested.”