The Story of the Ghosts, or How to Build a Forest (Part One: Sketching Ghosts)

photo credit: Jake Silco

Trey Anastasio: It’s my favorite thing to do. It’s so scary. I walked out on stage in Maine, on the first night of the tour, and it was so different.

Over a 35-year career, Trey Anastasio has performed in a rock quartet and with symphony orchestras, with cosmic free jazz big bands and Broadway pit musicians, with collaborators he’s had for decades and players he’s only just met. However, Ghosts of the Forest constitutes something new for him. And not just new in the sense that of an original album and limited edition band, but a new kind of new altogether.

Ghosts of the Forest–the album and ten live performances with an additional dozen songs–remains its own body of work, self-contained and unlike anything else in Trey Anastasio’s career: a crafted stage show with two hours of unheard music, deeply personal lyrics, and platforms for improvisation.

In part, the project was a tribute to Trey Anastasio’s close friend Chris Cottrell, who succumbed to adrenal cancer in January 2018. Not long before, Anastasio had lost his sister. And, just after Cottrell’s passing, Trey Anastasio Band keyboardist and old friend Ray Paczkowski fell ill with a brain tumor. It was a tumultuous and emotional time. Anastasio enlisted close musical friends Jon Fishman and Tony Markellis, and eventually Paczkowski himself.

But despite its introspective roots, spectral name, and the radical notion (for Anastasio, anyway) of performing a fixed song-list each night, Ghosts of the Forest was hardly a grim monument. In tribute to Cottrell, who loved the adventurous side of his friend’s bands more than anything else, Ghosts of the Forest became a container for the present moment — and each ensuing present moment that existed as the project unfolded.

There was an album, too, released on the eve of the tour. But, as with much of Anastasio’s music, it was most alive during performance, a tangible and illuminated thread. Lift the bell jar and see.

Trey Anastasio: I’m kind of always writing, so I think something was being born, and I didn’t quite know where it was going. And then this thing started happening with Chris. But the project was actually started before that became the event of the day. I try to keep a “no resistance” relationship with music, just open and in the present moment all the time. So, then, things that happen in the present start to affect the direction of where things are going. And my experience–sitting with Chris in his last moments, drifting in and out of sleep–is what informed it and shaped it into what it was. It grew in an organic and natural way, because of the timing of all this.

After this whole thing was over, I started thinking that it had just happened so fast, this outburst of music, writing and arranging and playing. I found myself asking, “what was I lamenting here?” Everybody’s friend dies. It was a profound loss, but It still felt like there was more beneath the surface. It really haunted me.

I’ve been trying to put two and two together after the fact. I think a lot of it is about the loss of that naive feeling, all that stuff you feel when you’re a kid. And when that goes away you have to get a new mojo. And maybe that’s what it was about — more than the loss of an individual person, that this was the person that tied me to my childhood outside my work world. He was a tether to “Let’s go ride a fuckin’ raft down a river in Utah and camp out for six days in a tent,” which we did, and look back and realize you’re really not supposed to put a tent right next to a river because the river rises sometimes and people die. But we did that. It was stupid, but it never even crossed our minds. Eventually, you get too old to live that way anymore. It’s right around the age that I am now. So maybe this is more lamenting the loss of that than an individual.

Ray Paczkowski: When I was in the hospital, Trey would come over all the time, and we were talking about Chris and what happened to him. I’d known Chris for many years. It was kind of surreal to be in a hospital room, and I wasn’t sure what was going to happen, but I was pretty sure it’s going to be fine, because that’s what I was told. Trey was definitely a little crazed about it all, that I might be headed off into the other world. I think when Trey freaks out, [his personality] just gets even more Type A.

Don’t mistake the ghosts for the forest.

Where Phish have become infamous for never repeating a setlist, playing more than 230 different songs during their 13-show Baker’s Dozen run at Madison Square Garden, Ghosts of the Forest negated the notion of setlist score-keeping almost entirely. During their 10-show tour in April 2019, the band performed a fixed sequence of music. As Anastasio points out, the project wasn’t a theater piece. But it wasn’t quite a rock concert either. While the music was rehearsed and tight, and even scripted to some degree, there was flexibility and room for improvisation.

Anastasio and Phish have escalated their game over the years, from one-night-only big picture set pieces to slower long-term evolutions. But Ghosts of the Forest stands alone as a single focused moment, a standalone two-and-a-half-hour night of music consisting of 21 songs, a four-piece band, two additional singers, and staging by Abigail Holmes, meant to be performed and experienced live. It also represents perhaps his biggest step as a lyricist. Often a collaborator, Anastasio’s truly solo compositions likewise thread through his career, his lyric writing growing more nuanced and personal over the course of decades. Ghosts of the Forest represents the largest and most cohesive batch of lyrics entirely by him, and unquestionably the most personal.

Trey Anastasio: Chris was an elk hunter, but he wouldn’t get an elk most years, he just loved being high up in the Rocky Mountains. He told me that there was this Native American term, “ghosts of the forest,” to describe elk, because they would vanish into the woods when you are tracking them. They’re very hard to hunt. He’d told me how he’d be following a trail, and it would suddenly just end, as if the herd had all leapt sideways. You never knew when the trail would end.

Finally, one year he got an elk. He was all alone when he shot the elk, and he told me about this eye contact moment. It gave me chills. He dressed the elk in the proper way, which he was very proud of, and carried the elk meat all the way down the Rocky Mountains alone, hundreds of pounds of it. I would come over, and he would serve it to us. It lasted for a long time. There was an elk rug on his floor when you walked in his house.

It was the only elk he ever got, but I remember there was a change. There was a sense of pride, a spiritual shift. I could tell when we talked that it was a very big deal to him. It made me reassess my point of view about hunting, because there was nobody who loved nature more than Chris. When he died–and I was sitting with him, playing guitar, as he drifted into the spirit world–I thought back about that.

Helping to build on the narrative was Abigail Holmes. A concert design veteran with a multi-decade genre-spanning resume, one early credit that attracted Anastasio was her work with Talking Heads during their pivotal Stop Making Sense tours. Serving as lighting director for the genius re-imagining of a live rock performance–a show that a teenage Anastasio caught several times–Holmes worked with David Byrne again recently on his spectacular fusion of color guard and live music, Contemporary Color. She’s partnered with Janet Jackson, The Cure, and Roger Waters, helping the Pink Floyd songwriter stage The Wall in Berlin. She’s collaborated with longtime Phish lighting director Chris Kuroda to design the band’s last two light rigs, including the bold LED screens that surrounded the band in 2016, as well as the new movable rig that debuted in 2017. Anastasio enlisted her as a collaborator before the Ghosts even had a discernible shape.

Trey Anastasio: Abbey [Holmes, production designer] and I started to meet early on. We had coffee before I even finished writing the songs. She was kind of talking to me as it was being written, and we would talk about theatrical concepts. We talked about why you need to be, as an artist, completely concrete in the narrative and the intent behind every line, in every musical choice — even though it’s not important that the audience exactly knows my concept. But if I put nonsense in there, their radar will go off.

From a musical perspective, having Fish and Tony seemed like a place to start. They’re my close friends, which was important based on the subject matter. And it was important that it was neither Phish nor TAB as a starting place, and we started off just the three of us.

Jon Fishman: There was also a very clear element of Trey saying things like “I’ve always wanted you and Tony to play together. I kind of play with a certain abandon. And Tony plays with a certain grounded-ness. He can definitely stretch out and I can definitely tighten up, but he’s very grounded. You never have any fuckin’ doubt where the one is when you’re playing with Tony, or where the groove is, or the feel. And that makes it easy for me to get a little bit wild-eyed and play to the edge of my skill set.

Tony Markellis: I’ve been fortunate enough to play with a lot of great drummers over the years, but Jon is a whole different animal. His playing is such a balance of delicate detail with explosive, raw animal energy — a rare combination of freedom and precision. I’d go so far as to call his drumming melodic.

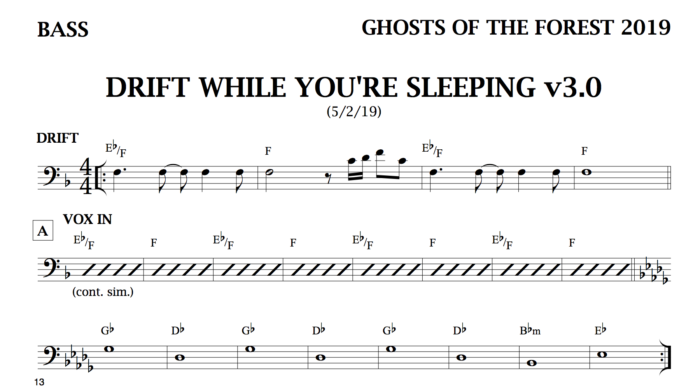

Trey Anastasio: Tony likes charts, so I’d make a chart for Tony. With Fish, I sent him [demos of] all the songs and he just went home and practiced. He’s a practice addict. He showed up knowing everything. For “Drift While You’re Sleeping,” he came up with this beautiful drum part that’s all sculpted.

Jon Fishman: I love every single one of these songs. As a songwriter, I think Trey really upped his game with this particular material. Not that the material suddenly became serious in the sense that there’s no humor to it. But, you know, Trey’s sister passed away. His best friend passed away. There was a scare with Ray. There’s a lot of death around us. Things get real. I think there was a focus on the realness of life as he experienced it up to this point, and trying to say things in a straightforward manner, and not sugar-coating. The focus was on the realness of the life experience and the beauty of the world, and the beauty of music.

Trey Anastasio: After Chris died, and I’d finished making the album, I went on a cavern tour in Utah, next to a Navajo reservation. I had a Navajo guide who started talking to me about elk. He said that when a boy turns into a man in his culture, they go hunt for an elk with a bow, and when they shoot the elk they become a man. They believe in this passage of the elk’s spirit to the natural world.

And, when the guide told me that, my head was exploding. I’d just finished the album, and the very beginning of the album–the very first lyrics of the opening song–was my attempt to write from the point of view of the elk, as Chris and the elk make eye contact in the woods: “And you’re the one to take me down, so take me down.” The Ghosts of the Forest idea is that Chris has now died and gone to that spirit world; they are together, one spirit, and that’s what the album cover eventually became, the spirits commingling in the woods.

***

Part Two: Growing Ghosts