That ’70s Cult Band: Big Star Remembered

In October, Relix looked back on Big Star’s career as the cult heroes prepared to release a new box set. It turned out to be one of the last magazine features on the band to appear in singer Alex Chilton’s lifetime. Below is a complete copy of the article.

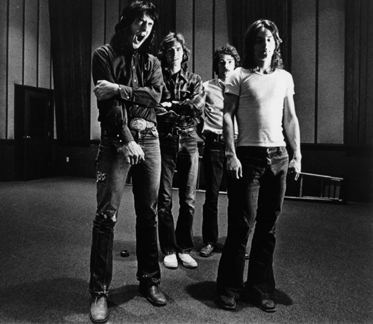

Photo by John FryIn the 35 years since Big Star’s original lineup dissolved, they’ve been the direct and indirect inspiration for scores of bands and artists, casting a huge shadow across the history of indie rock. Back when the band was initially recording and releasing records, though, it was barely a blip on the rock and roll radar. If you’re an indie rock fan, you’ve probably heard a Big Star song, whether you know it or not. “Thirteen,” from the group’s debut album #1 Record, has been covered by Wilco, Elliott Smith and Garbage, among others, while The Bangles redid “September Gurls,” from its second disc, Radio City. The group also managed some aboveground pop-cultural penetration: Cheap Trick recorded the #1 Record track “In the Street,” which served as the theme song to the sitcom That ‘70s Show for eight seasons.

Big Star was essentially an outgrowth of Memphis singer/songwriter Chris Bell’s band Icewater, which included bassist Andy Hummel and drummer Jody Stephens. Alex Chilton, a friend of Bell’s for several years who’d had a couple of hit singles ( “The Letter,” “Cry Like a Baby” ) as vocalist of The Box Tops joined the trio. The four were part of a tight-knit crew that hung around Memphis’s Ardent Studios, the backup recording location for Stax Records and host to sessions for Isaac Hayes, Sam and Dave, and Booker T. & The MGs, as well as ZZ Top and Led Zeppelin. Owner John Fry ran both an unofficial “recording academy,” teaching young local musicians the ins and outs of the studio, and Ardent Records, Stax’s rock imprint.

“I don’t wanna sound bigheaded or pompous, but I think we were our own scene,” recalls Andy Hummel. “Most people in Memphis were doing rockabilly or stuff that had evolved from rockabilly, or R&B and stuff that had evolved from R&B. There were a few of us who were really into British Invasion stuff, and I’m not sure a whole bunch of people in Memphis really were, [but] I don’t think it’s something where we consciously thought, ‘We’re different from the guys at Stax,’ or ‘We’re different from the guys at American.’”

Big Star recorded #1 Record in the summer and fall of 1972, and released it toward the end of that year. It featured 11 songs and a one minute-long outro, the enigmatically titled “ST 100/6.” The opening track, “Feel,” is a three-minute manifesto. Over strummed acoustic guitar, which is soon doubled by a distorted electric guitar and bolstered with a round, full bass line, Chris Bell sings “I feel like I’m dying/ I’m never gonna live again/ You just ain’t been tryin’/ It’s gettin’ very near the end.” It could be a typical rock and roll anthem of sexual/romantic frustration, but it’s much more. The sharp pain in Bell’s high-pitched vocals, and some unexpected left turns in the arrangement (the buzzing saxophones that appear after the second verse, never to be heard again), mark it as something familiar yet wholly new. In the coming years, this sound – high vocal harmonies, instantly memorable choruses, sugary lyrical sweetness with a slightly cynical edge – would come to be called “power pop,” and become a codified style. Think The Knack, Cheap Trick, The Romantics and many more. But in 1972, this was something that Big Star (and, to be fair,

Badfinger and The Raspberries) were doing in relative isolation.

Other tracks on #1 Record, such as “In the Street,” “Don’t Lie to Me” and “When My Baby’s Beside Me” offer a crunching, catchy, basic rock and roll sound that’s echoed in the discography of acts from Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers and Cheap Trick to the early KISS albums. But these are balanced by ballads such as “Try Again” and “Give Me Another Chance,” which showcase the plangent beauty of impeccably recorded acoustic guitars and Chilton and Bell’s vocal harmonies. The emotion mustered when the singers stretch above their normal range gives the melancholy lyrics (mostly by Bell) an unexpected power. As a whole, #1 Record is that rarest thing – an album that is both immediately rewarding and possessed with depths that only reveal themselves over time. The deceptively simple arrangements unfold gracefully like flowers blooming in time-lapse photography, making it a record that one can return to for years on end.

#1 Record should have made a commercial splash. At the time it was released, though, almost no one heard it. Stax had signed a distribution deal with Columbia, which in theory should have sent the soul label’s releases into every record store in the country. But almost as soon as the ink dried, Columbia head Clive Davis was ousted, and many projects died with his departure – the Stax deal among them. With no money to do so, the task of promoting Big Star landed back in John Fry’s lap. “We were trying to do what we could,” he recalls. “Basically what we had to work with on the marketing front was critical acclaim from the rock press – which was not nearly as widely circulated or as immediate as it would be today in the Internet age – and the radio support we had from all these FM radio rock stations that were starting up.”

Fry believes that the band might have been able to build an audience through live performances, but that didn’t happen, either. “They didn’t have a booking agent, they didn’t have management,” Fry says. “As I look back on it, it could have made a big difference if they’d gotten out there and played live extensively. But [while] it wasn’t like they hated to play live, this was in the post-Beatles era, where you have folks looking and saying, ‘those guys just became a recording entity and stopped playing live altogether.’ I never heard that verbalized, but it’s got to [have been] in the back of someone’s mind – that if you just record some good music it’ll find some way to get out.”

Andy Hummel sees things even more starkly than Fry. “We were a studio band first and foremost – and always – and when we played live it was a huge stressful deal that we all freaked out about,” he recalls. “Those times when we did play live, it didn’t seem like there were a whole bunch of people who wanted to hear us, unless the audience was a construct like it was at the Rock Writers’ Convention, where they actually brought people in specifically to listen to us.”

Photo by Mike O’Brien, courtesy of RykodiscThe First Annual National Association of Rock Writers Convention was organized by John King, an independent publicist hired to help salvage Big Star’s career. Ardent paid to fly in (and put up) as many rock critics as the label could find, including Lester Bangs, Richard Meltzer and Cameron Crowe. The convention had panel discussions, food and drink, and on the final night of the three-day event, Big Star performed. However, the band played as a three-piece – Chris Bell had already left the group, despondent over #1 Record’s lack of success.

“Things really got bad after the first LP went out…the whole commercial end of the endeavor had gone south so badly,” recalls Andy Hummel. “We put together a record that we thought was good, and apparently the judgment of history is that it was pretty good, ‘cause here it is 35 years later and people are still interested in it. But the people who were supposed to carry the business end of it just failed miserably. That was very frustrating for us as artists, especially Chris. It was very difficult for him because he was obsessed with being a famous rock and roll musician and this was interfering with his plan.”

Bell’s older brother David concurs. "I know for a fact that [Chris] was just so horribly disillusioned and disappointed that #1 Record didn’t do really anything at the time, when everybody who heard it – and certainly rock critics – all had glowing things to say. "I’m quite certain that he was probably having his first full-blown depression.

“Everything he ever did was out of place in Memphis,” Bell continues. “He wanted to smash guitars and have strobe lights and all The Who business, where most people [in Memphis] were wanting to hear some sort of Stax [sound or] whatever was contemporary at the time, but nothing that was a little bit avant-garde or was coming from England, and his focus was always what was coming from England.”

Chris Bell drifted around for a few years, accompanied by his brother, moving to England and gigging intermittently while trying to get a record deal as a solo artist. He wrote a few songs for the second Big Star album and recorded a single, “I Am the Cosmos/You and Your Sister,” on which Alex Chilton provided backing vocals. Over the course of a couple of years, Bell compiled enough material for an album (also titled I Am the Cosmos), despite struggling with drug addiction and depression. Only the single appeared in his lifetime, though. Shortly after Christmas 1978, Bell died when his car struck a telephone pole. Ultimately, I Am the Cosmos was issued on CD in 1992.

With Bell gone and #1 Record an abject commercial failure, the other members of Big Star also felt their enthusiasm wane, and the group effectively split. But the Rock Writers Convention gig – where the performances of #1 Record tracks and selected covers were rapturously received – rekindled Big Star’s creative fire, the group returned to Ardent Studios to work on what would become Radio City. Though it primarily features the trio of Chilton, Hummel and Jody Stephens, Bell contributes a few songs, notably “Back of a Car.”

The album is more ragged and more rocking than #1 Record; the most notable change is in Stephens’ drumming, which has transformed from pristine timekeeping to genuinely driving the band forward through funky, complex grooves. Album opener “O My Soul” is a thick, sinuous jam, with Chilton’s lone guitar shadowed by Hummel’s powerful bass and Stephens’ stumbling drums. The groove is irresistible, but strangely off-kilter, almost pointing toward the deconstructionism of the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion. A weird aggression pops up frequently on the album, though it’s balanced by the acoustic ballads “September Gurls” and “I’m In Love With a Girl,” the weird piano and vocal interlude “Morpha Too,” and Chris Bell’s more overtly melodic, British Invasion-influenced contributions. Radio City is not nearly as seamless of an album as #1 Record; it throws more curve balls at the listener, exchanging the radio-friendliness of the debut for a cocksure defiance that can almost be seen as a middle finger to the executives who had failed to market Big Star’s poppier work.

Bassist Hummel emerged as Chilton’s songwriting partner on Radio City, a role he seems to have adopted reluctantly. “The big drivers on that first LP were clearly Chris and Alex,” he says. “My role sort of changed a lot after the first LP, as I had a chance to learn how to operate all the equipment in the studio and spent some time getting my chops up musically as well. Somebody had to pick up the slack and I sort of gave it a shot.”

Radio City marked the end of Big Star’s initial lifespan, though. Almost as soon as the album was released, Hummel left the group. “It was time for me to go register for my senior year [of college], and the band was getting ready to go off and try to do some serious touring, and the two couldn’t go together,” he says. “I couldn’t do it and still finish college. It doesn’t seem like a long time now, but for nearly four years, none of us had made any money. We were all still living with our parents except Alex, who had money from his life as a Box Top. We didn’t have jobs except playing music at Ardent and that didn’t look like it was gonna sustain us. So I left – which at the time seemed like the obvious choice – finish college and see if I could make a living doing something.”

Chilton continued recording with Stephens and various studio musicians, in intermittent sessions that eventually became Third/Sister Lovers, a weird and depressed album that some might argue was only credited to Big Star for commercial purposes. And by the time the record was released in 1978, the group’s first two had been paired as a double disc, and a cult was beginning to form.

Throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, old vinyl copies of #1 Record and Radio City were taped and traded among musicians who formed bands like R.E.M., The dBs and Teenage Fanclub, to name but a few. The former members of Big Star, though, had moved on with their lives: Stephens was working at Ardent Studios, Hummel was an aircraft designer in Texas and Chilton was barreling down an increasingly weird and hermetic solo path, producing records for The Cramps and playing with mutant rockabilly act Tav Falco’s Panther Burns. His solo discs featured as many covers as originals, and he rarely dipped into Big Star’s catalog when playing live.

Then, out of nowhere, in 1993, Chilton and Stephens reformed Big Star with two members of The Posies filling Bell’s and Hummel’s spots. Twelve years and a few European and Japanese tours later, that version of the band recorded In Space, a studio album that, like Third/Sister Lovers, had more in common with Chilton’s solo career than Big Star’s two canonical discs. And now there’s a box set, Keep An Eye On The Sky, four discs of demos, alternate mixes, Chris Bell’s solo single, some Icewater and Rock City tracks, and a full disc of live recordings from 1973 featuring the trio version of the band playing songs from both albums and covering Todd Rundgren and Kinks tracks, among others. The band performed in London in June and there are rumors that it might do show domestically.

Thirty-five years after the original incarnation of Big Star dissolved, a full-on exploration and celebration of this pioneering power pop group is underway. And while the questions sparked by the band’s art and career – can a group that never sold any records truly be called “pop” ? Is pop a sound or a description of commercial status? – will never truly be resolved, the music speaks for itself.