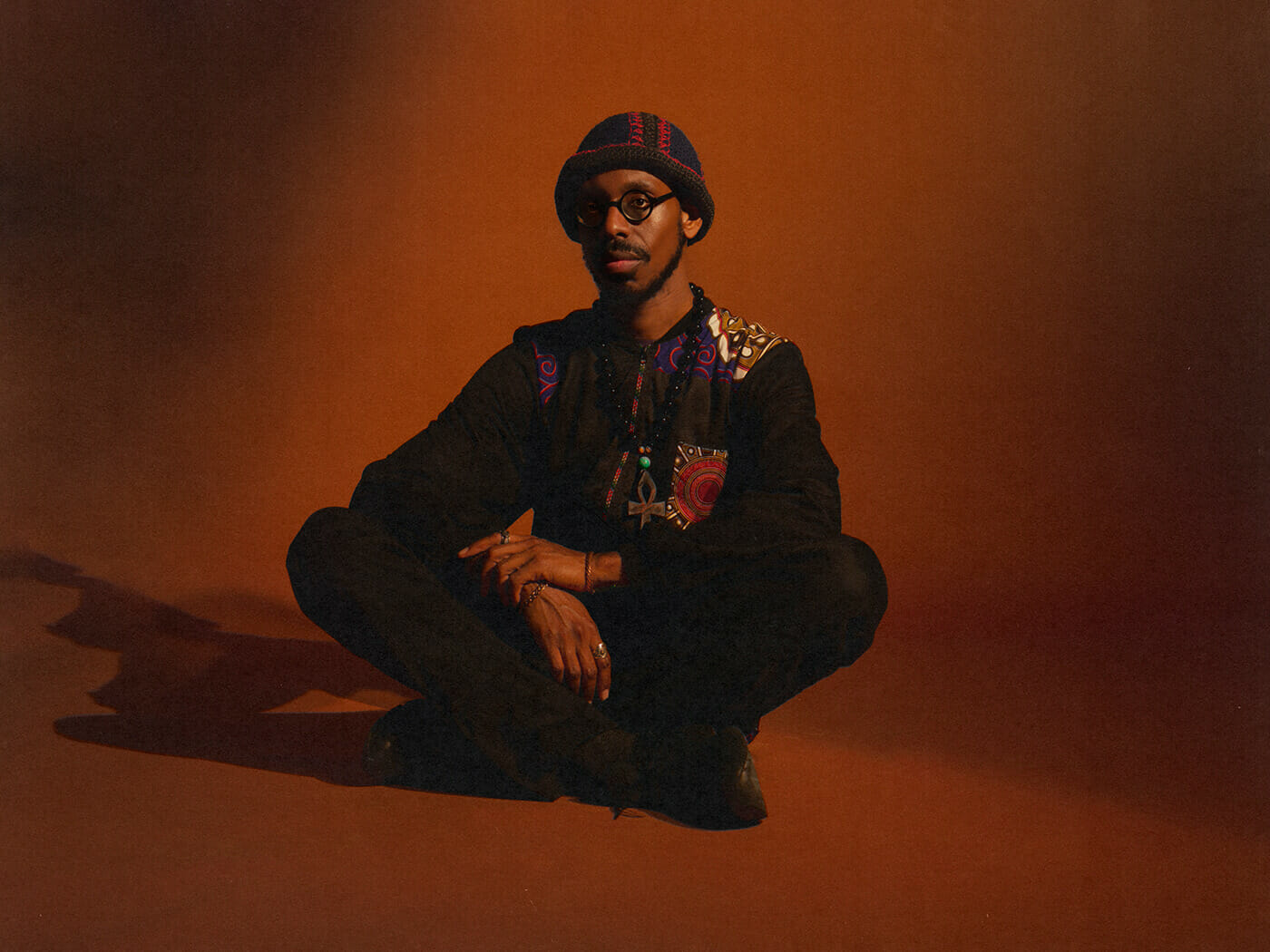

Swing Time: Shabaka Hutchings

photo credit: Udoma Janssen

***

For someone whose playing is often aggressive, propulsive and frenetic, London jazz bandleader Shabaka Hutchings is surprisingly restrained, even meditative, on his latest album, Afrikan Culture.

“There’s a tempo and a pace in terms of how you make the music, which is slower and more considered,” Hutchings says of Afrikan Culture, his first release under the name Shabaka. “The idea isn’t to rouse people up in a franticness. It’s actually trying to get people to be stiller.”

The set finds the horn player, best known for his saxophone prowess, shifting gears and focusing on the flute. “This is an album that dwells in that space and makes that the center,” he says. “That’s opposed to that area being the tagalong to something that’s more hyped and instantly gratifying on an intensity level.”

The latter might be more descriptive of Sons of Kemet, the adventurous double[1]drums-and-tuba outfit that the saxophonist leads, or his The Comet Is Coming combo, a synthy psychedelic trio that’s due to put out its fourth album this fall. Or maybe you’re thinking of Shabaka and the Ancestors, the mostly South African sextet that explores the African diaspora from all corners of the cosmos and released We Are Sent Here by History as the pandemic took hold.

Keeping track of Hutchings’ myriad projects—he also has a book in the works—can be exhausting and confusing. But, though one might think that it’s a challenge for the 38 year old to separate each band in his head, he actually finds it quite easy to compartmentalize his various groups.

“It becomes difficult when you try to think about it, but if you actually just act intuitively, it’s easy,” he says. “If I’m writing something for Sons of Kemet, I am writing for Theon [Cross] and Tom [Skinner] and Eddie [Hick]— those specific individuals. And it’s really simple because certain dynamics and the way that we all play suggest [a certain approach]. Whereas with Comet, that specific combination suggests another idea of melody and a different temperament—musically.”

If there’s a throughline to Hutchings’ many projects, then it’s a simple one—him. “That’s how I see it,” he says. “I’m just trying to be myself in different contexts. This may be a thread that’s quite complex in terms of what I’m interested in and how I position myself as a kind of African diasporic person.”

Hutchings, who was born in London but came of age in his parents’ native Barbados, uses his music to explore African culture and he continually challenges the listener to learn more— tackling race, oppression and Black Lives Matter through song titles and spoken-word narratives (often from poet Joshua Idehen, who has guested with Kemet and Comet). But the message isn’t always clear or obvious, which is the point. “Sometimes, if you give people too much information, then there’s no work that they need to do because you’ve done all the work for them,” he says. “I like to think the unpacking is the message—that things just need to be unpacked. You think, ‘Start here and just continue forever.’”

Musically, his groups often look to the past while simultaneously pushing toward the future. Each project is out there and experimental in its own way, stretching the definitions of jazz and African music. “If you see these ideas of past, present and future as being a kind of cyclical continuum, then all [my] groups deal with the past in order to have a vision of the future. But, all the groups still exist in the present moment,” Hutchings says. “And all of them deal with a particular element of the past. Because of the non[1]genre based approach, they’re not trying to fulfill very rigid rules of what the music should be. When you view the music, you’re projected into the future because you don’t feel like you’ve heard it before.”

One of those bands, however, is about to become a thing of the past. Despite releasing the acclaimed Black to the Future set last year, Sons of Kemet recently announced that they “will be closing this chapter of the band’s life for the foreseeable future” after finishing a batch of 2022 tour dates.

“Who knows?” Hutchings says of the decade-old band’s future. “Everyone didn’t necessarily want to make an announcement but I definitely thought, ‘If I was a fan of a band and there was a break coming up, then I would want to see one more gig.’ At the moment, we’re just saying it’s stopping, and then we’ll just see what the future brings. It’s that point where everyone has other things to do.”

Sons of Kemet drummer Skinner is playing with Radiohead’s Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood in The Smile; tuba player Cross has solo projects and Hutchings has his calendar mapped through 2024, starting with a Comet Is Coming tour this fall. Then, Hutchings says, “I just want to focus on my own music, which is more down the texture of African culture. The only way to do that, for me on a personal level, is to actually fully commit to doing things that way—at least for a period of my life—and focus on making that music.”

The new Afrikan Culture hints at that future, which finds him leaning on woodwinds like the shakuhachi (a Japanese bamboo flute). “I’ve actually been focusing on the flute a lot more than the saxophone in recent years, but the bands that I play in have the saxophone written into the way the music’s constructed,” Hutchings says. “With Afrikan Culture, the audience is brought up to date to what I’m doing when I’m not doing the gigs with the bands.”

Hutchings has also recently spent time recording at Rudy Van Gelder’s famed New Jersey studio with such renowned American jazz musicians as bassist Esperanza Spalding, drummer Marcus Gilmore, pianist Jason Moran and multi-instrumentalist Carlos Niño. “I’m spending my time with the material and crafting an album from it,” Hutchings says. “It’s all gonna be on flutes and clarinets.” And despite working with musicians who often play in the traditional jazz space, he says, “The music doesn’t sound anything like what you would associate with traditional jazz. It’s just using them as creative musicians to get into a space and to make that space.”

The vision for that space is becoming clearer by the day. Just recently, he jotted down a mission statement of sorts, a guiding light as he maps out the next chapter of his sonic evolution: “I want to make music which looks into the distance at dawn or dusk.”