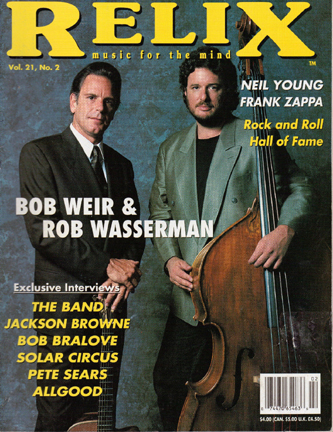

Rob Wasserman: Bass-ically Unique (Flashback Friday)

Celebrated bass player Rob Wasserman passed away on Wednesday at age 64. Today we look back to our Jan/Feb 1994 issue which featured this article on Wasserman.

Rob Wasserman’s resume is so full, it’s ridiculous. To say that the tall, curly-haired bassist is in demand is an understatement. It is no wonder because Wasserman, at 41, has already accomplished much. He has recorded and toured with legends, garnered acclaim in Critics’ and Readers’ Polls and even earned music’s coveted prize, the Grammy.

Some of the California native’s collaborations include funky pop with Oingo Boingo; soulful rock from Ireland with Van Morrison; fast-pickin’ bluegrass and swing with David Grisman and Frenchman Stephane Grappelli; soulful female rock with Rickie Lee Jones; blues with the man who gave the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin something to sing about — Willie Dixon; urban rock poetry with Lou Reed; and his most recent association — an acoustic duo with Grateful Dead rhythm guitarist, Bob Weir. In addition, Wasserman has also managed to put out two critically-lauded solo albums.

Now he has finally released the long-awaited Trios on MCA/GRP. This astounding third album and final installment in a unique trilogy built around the acoustic and electric upright bass is also a bizarre mesh of new live-in-the-studio recording that refuse to follow pop trends or rules. The release is accompanied by a 32-page art book that highlights photographs of the many sessions as they were being performed. This high budget, spiral bound book will help propel the project in its marketing.

Featuring a smorgasbord of musicians from diverse realms of the rock, blues, jazz, alternative and classical worlds, Trios is a project like no other. The Grateful Dead’s Jon Cutler co-produced the 14 tracks with Wasserman, most of which were recorded at the Dead’s studio in San Rafael. Wasserman and his bass join forces with an eclectic collage of twosomes, and the results couldn’t be more varied: main Beach Boy Brian Wilson and daughter Carnie collaborate for the first time on the heartshaking “Fantasy Is Reality/Bells Of Madness;” Elvis Costello and Marc Ribot swing their way through their campy “Put Your Big Toe In The Milk Of Human Kindness;” Bruce Hornsby and Branford Marsalis jazz up “White-Wheeled Limousine;” Edie Brickell and Jerry Garcia wax strange and psychedelic on the spontaneous “Zillionaire” and the truly out-there “American Popsicle;” Willie Dixon and drummer Al Duncan groove on “Dustin’ Off The Bass;” Bob Weir and Neil Young strum neogrunge-like on “Easy Answers;” Chris Whitley and Primus leader Les Claypool play funky folk on Whitley’s “Home Is Where You Get Across;” and two inspired cellists, Matt Haimovitz and Kronos Quartet’s Joan Jeanrenaud, integrate beautifully the classical form and backwoods gypsy spirit. Wasserman’s specialized six-string Clevinger electric upright bass ties it all together.

Organizing 16 word-class musicians, however, proved to be a painstakingly slow process, soaking up five years in-between Wasserman’s other high-profile projects. “Some sessions were two years in just the scheduling,” cites Wasserman.

The most difficult tune to organize was the Wilson track, which is two pieces molded into one. The “Bells Of Madness” section was composed by Sam Phillips, wife of producer/musician T-Bone Burnett. Phillips is an accomplished songwriter in her own right and contributed the heartfelt lyrics. She poignantly captures the difficulty of a father-child relationship in a troubled family: When I hear the bells of madness ring/I will listen to the silence/Love is louder than anything/and peaceful in its violence.

Wasserman and the elder Wilson then added the “Fantasy Is Reality” bridge section, which is pure ‘60s style Beach Boys doo-wop harmony. “It was quite a challenge to put that together,” says Wasserman. “It was just a major venture; that one took the longest.”

Whereas such a diversity of material could threaten to disrupt the flow and cohesion of a concept album, Wasserman and his cohorts steered clear of possible confusion by remaining true to the spirit of improvisation and collaboration. It is, in fact, the spirit and variety of artistic freedom that provides its strength.

“It’s not a light album, it’s not like light beer or anything,” laughs Wasserman, and then adds in his casual understated tone, “you’ve gotta actually listen. It’s not a party record.

“The first side is more Western,” he continues, “the whole thing goes from West to East. West as in pop, a little more in the pocket, accessible, Western harmonies. And the other side gets more and more swampy, improv. That’s the way I wanted it. If you hang in there ‘til the end, it’s an adventure!”

Wasserman’s adventure began in 1983 with the release of Solo (Rounder), a fluid and sparse collection of bass pieces performed live with no overdubs. On Solo, Wasserman ably proves that a bass can simultaneously provide rhythm, melody and even harmony. Produced in part with the help of a composer’s grant from the National Endowment of the Arts, Solo attracted critics’ and fans’ ears alike.

In 1988, he stepped up to the major leagues with Duets, released on the giant MCA, featuring classy interpretations of old standard swing tunes, Tin Pan Alley songs, a specially written Leonard Cohen piece and several others. Performed by Wasserman and a handful of the best singers around today, Duets was nominated for three Grammys, won one (for Bobby McFerrin’s “Brothers”) and brought Wasserman a heaping load of glowing media praise.

Consequently, then, Trios begins where Duets left off, escorting the listener through five decades of musicians and several hemispheres of cultural influence on its strange journey from the Wilsons’ opening number to its Garcia/Brickell conclusion.

Sitting on the wooden deck of Bob Weir’s hillside Mill Valley home, Wasserman relaxes as he ruminates about how his trilogy came together. “[Solo] was sort of a sketch, an overall vision of what I wanted,” he explains. “It became more apparent when I was doing Duets. So one led to the next, and then I realized it was a trilogy. That seemed like it completed the cycle.”

Since Solo is just that, one bass and no special guests, it is also the lightest, in form and content, of the trilogy. Venturing into the land of flamenco and classical, Wasserman utilizes the bow to create a resonant, cello-like intensity. Beautiful and stark in its sparseness, however, Solo sets the stage for something bigger.

Duets takes the listener to a world before rock ‘n’ roll. The sparseness is still there, but this time there’s the added attraction of the splendid vocals of Aaron Neville, Rickie Lee Jones, Jennifer Warnes, Dan Hicks, Cheryl Bentyne, Bobby McFerrin, Lou Reed and the crisp violin of master Staphane Grappelli. Putting composition aside for the moment, Wasserman and his eight duet partners play “songs they’ve loved since they were little.” Except for one bass duet (with himself) and McFerrin’s own “Brothers,” all of the pieces on Duets are standards from earlier decades. Jones’ contribution is a piece her father wrote and sang to her when she was a child.

Unlike many of the so-called duet albums of recent years, Duets takes the name literally and features actual live duets. “That’s what bothers me about all these duets’ albums that are coming out,” says Wasserman. “If you call two people singing amidst a sea of sidemen, ‘duets’, then I don’t know what a duet is anymore.”

For example, Frank Sinatra’s recent all-star ‘duet’ album had the manufactured aspect of Sinatra recording all of his parts first and having the other singers put their parts on at a later date. “From what I’ve heard,” says Wasserman, “[Sinatra] never even saw half of the people he recorded with. Not only that, they used orchestras and bands. To me, a duet is just two people.”

And, as Wasserman is quick to point out, the same rule applies for Trios.

“Trios is just three people a track,” he emphasizes, “and if sometimes it sounds like twenty, it’s because we’re playing twenty parts, but it’s still the same three people. No side people allowed.”

And while the concept of recording reach tune live in the studio remains the same, the big difference with the new project is that each song is a new one. The exception is blues pioneer Willie Dixon’s contribution, “Dustin’ Off The Bass,” which he wrote thirty years ago.

Following “Country” (part one of Wasserman’s own instrumental trio that is interspersed throughout the album) and “Zillionaire,” comes the gruff voice of Dixon barking out his lyrics “Rub it!” in true blues fashion. Dixon and Chuck Berry drummer, Al Duncan, slide into the mix with a smooth and swinging drum part. “You can’t get a machine to play that,” says Wasserman.

“[Dixon] did [“Dustin’ Off The Bass”] with his son who was a bass player,” Wasserman explains, “as a way to jam on stage with two basses — upright bass and electric bass. They did that for years in the show. And then we met, and I told him I wanted to do a tune with him playing bass, and he immediately wanted to do that because that was the one he’d always done with his son.”

Wasserman, who is dedicating Trios to the late bluesman, was asked by Dixon to be a part of his Dream Band in 1990. “We were gonna do a bunch [of shows],” recalls Wasserman. The whole idea, originally was for him to be the emcee and play bass with me, like he did with his son on a couple of tunes. But then he got sick. I talked to him, and he said that was the first gig he missed in twenty years. Then he died; it was real sad. I was extremely honored that he’d considered me someone he wanted to play his bass parts. I was sort of astonished.”

“As far as I can see,” offers Bob Weir upon joining us at his home where our interview took place, “there’s about nothing god on the face of this earth that you couldn’t dedicate to Willie.”

Weir’s own contribution, “Easy Answers,” comes after the Dixon tunes, barreling out like an industrial assault. With lyrics supplied by Robert Hunter, the tune is actually credited to five people, looking like a law firm on paper: Weir, Wasserman, Hunter, (keyboardist Vince), Welnick and (Grateful Dead MIDI and computer expert) Bob Bralove.

“I came up with an ascending progression a couple of years ago,” Weir says of the tune, “and I had it sort of worked into another tune, and then I got dissatisfied with the rest of the tune, but I liked the ascending progression.”

Recorded at Neil Young’s home/barn studio, “Easy Answers” features both Young and Weir playing electric guitar in the same room, providing for a crossover of heavy, distorted rhythm guitar. Wasserman’s electric bass has never sounded more sinister.

“It’s edgy,” says Weir. “It sort of hangs on a flat-5 for a long time, which is not the most tonic [note]. Hunter did the lion’s share of the lyrics,” he continues. “I did the lion’s share of the music, but there were other people who got stuff in there, so we just incorporated them in the authorship.

“It’s an example of why one writes a song to get across a point or a feeling…because sometimes just words won’t do,” Weir further explains. “Words in poetic form with music, will. It’s like Willie Dixon. If you read his lyrics off of the page, they’ll oftentimes seem just sophomoric. But once you sing them with the melody, it all falls together, and we’re talking serious poetry.”

Both Weir and Young’s heavy guitar sounds on “Easy Answers” are reminiscent of Lou Reed’s distorted guitar on “One More For The Roads” from Duets. “Neil had a seriously altered signal path,” says Weir. “One of the reasons I liked that particular ascending progression was because I was getting the sound of as circular saw. That was interesting to me. To have a sound that’s the edgy for these edgy lyrics, I thought it fit particularly well. Actually, I came up with that riff early on in the process of writing it, and Hunter was listening to it, and I think that might have sort of coaxed him into the direction he went. So, marrying up the lyric with the feel.

“I think we did two takes. We took…the second take, it might’ve been the first take,” Weir looks to Wasserman. “I’m not sure. Neil doesn’t like to spend a lot of time. I think we recorded six verses and cut out a couple. For instance, my guitar solo, I didn’t know I was taking a guitar solo at the time!” Weir laughs, “Neil thought that that was perfect.”