Reflections: John Simon

The Band’s defining early producer and unofficial sixth member celebrates the 50th anniversary of his monumental year behind the board.

When John Simon says that “1968 was a good year for me,” he’s making an understatement, to say the least. In that fleeting 12-month span, the producer racked up the following credits: Big Brother & the Holding Company’s Cheap Thrills, The Band’s Music from Big Pink, Simon & Garfunkel’s Bookends, Blood Sweat and Tears’ Child Is Father to the Man, Gordon Lightfoot’s Did She Mention My Name and An American Music Band by the Electric Flag. And, if you push that time frame back just a slim month to December 1967, you could add his work on Songs of Leonard Cohen, the poet-musician’s rapturous debut. “It all comes down to what I like,” Simon admits. “If my tastes are in line with the artists—as it has been with most of the ones I’ve worked with—then everything works out great.”

So great, in fact, that many of the albums in Simon’s canon rank among the most pivotal releases of the last half-century. To pull back the curtain on his key role in those projects, the now 77-year-old Simon has just published Truth, Lies & Hearsay: A Memoir of a Musical Life in and out of Rock and Roll. Adopting a jocular tone, the book avoids axe-grinding, but does include some terse record-straightening. Simon bats away hearsay that his production credit didn’t originally appear on the cover of Cheap Thrills because he hated the music, or that he convinced Janis Joplin to dump Big Brother or that Leonard Cohen disliked the orchestrations that Simon added to his debut.

Instead, Truth, Lies & Hearsay details an obsession with music that dates back to when Simon’s father taught him violin and his main instrument, piano, at the tender age of four. Originally inspired by musical theater, he began writing songs in high school and continued to craft musicals after enrolling at Princeton University (including one that somehow refigured Macbeth with a happy ending). Upon graduation, he took a job with Columbia Records as a “trainee,” moonlighting at night as a songwriter for musical revues like The Mescaline Hot Dance, which was based on Timothy Leary’s experiments with LSD. His first projects at Columbia were spoken-word pieces. One captured parts of the McCarthy hearings, another chronicled Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium Is the Message. Simon served as an apprentice to Goddard Lieberson on a series of Broadway cast recordings, like the Stephen Sondheim bomb Anyone Can Whistle and a production of Hamlet starring Richard Burton. His pop crossover, and first production credit, came in 1966, when he oversaw The Cyrkle’s smash hit “Red Rubber Ball,” a song co-written by Paul Simon. His key contribution to the record was an organ part. “Essentially, I’m an arranger,” Simon said. “I’m not an engineer. I don’t know a bolt from a knob.”

Simon and Garfunkel had already started Bookends when he was brought on by Columbia honcho Clive Davis to “move them along. They were going very slowly,” Simon recalls. “We hit it off great, but I couldn’t move them any faster than they wanted to move.”

In fact, the project took so long that Simon had to leave after completing just three tracks. He was already set to produce Leonard Cohen’s first LP. “Leonard was supposed to be working with John Hammond,” says Simon. “But he kept cancelling, so he asked Clive for another producer, which was me.”

Though a seasoned poet and older than most rock-era stars, Cohen “wasn’t a very confident performer at that point,” Simon offers.

Besides some lovely orchestration, the producer also added something that became a central motif in Cohen’s career. “So many of his songs were about women, so I figured I would try adding women’s voices instead of sustaining horns,” he notes.

The next project represented a major step ahead in his career, especially financially. Al Kooper suggested he leave Columbia to work as an independent producer. “I was naïve; I had no idea producers got royalties,” reveals Simon.

His work on Blood Sweat and Tears’ inaugural album birthed the so-called jazz-rock movement. “It was like a James Brown horn band but with more complicated arrangements.”

Another crucial connection came when Simon met Albert Grossman, Bob Dylan’s manager, who also worked with Joplin, The Band and Gordon Lightfoot. Simon reworked Lightfoot’s sound, augmenting his acoustic ballads with strings. “He didn’t get it at first,” Simon says. “Eventually, he liked it so much he started having concert dates with full orchestras.”

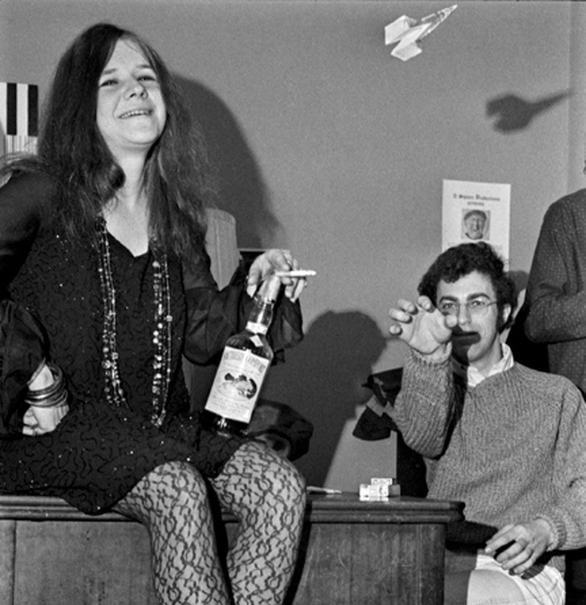

Simon also worked with Joplin and Big Brother & The Holding Company on Cheap Thrills, which was billed as a live album, though the end results are far from it. “After the success of their appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival, everyone wanted a live album,” he says. “We went to tape them at Winterland, and the band had all the energy, but they made so many mistakes. So we decided to make a studio album that was a fake live album because there was already a lot of publicity that they were going to cut it live. The only live thing is ‘Ball and Chain,’ though we changed the guitar solo.”

The only reason Simon’s name doesn’t appear on the sleeve is because an associate had, briefly, convinced him that “credit corrupts. If you don’t put your name on it, then it’s art for art’s sake,” he says. “Not the most commercial idea.”

Regarding the decision to ditch Big Brother, Simon believes that it probably came from Joplin or Grossman. Unlike others, he doesn’t single Big Brother out for their inferiority to the singer. “Janis outclassed every band she was with,” he said, including the excellent one on Pearl.

As much as Simon liked Joplin, he found his greatest rapport with The Band on their first two albums and The Last Waltz. Robbie Robertson has described Simon as part of the band’s brotherhood. “There was nothing that went on those albums that all six of us didn’t go for,” he says.

He yearned to join the group as a formal member, but Robertson told him: “We already have two piano players.”

The group’s seminal albums laid the blueprint for the Americana movement. “They started a new tradition,” Simon notes. “The Beatles and The Beach Boys stayed in the pop direction. But The Band went into more authentic folk, blues, early rock-and-roll and 19th-century music. They wanted to be considered important.”

And they instantly were, inspiring everyone from The Beatles to Eric Clapton to “ruralize” their sound. Simon went on to shape other significant works, including Mama Cass’ first solo album—which Dunhill label chief Lou Adler disliked because it shunned commercial expectations—and Steve Forbert’s late-‘70s album Jackrabbit Slim. “We recorded every single thing with Steve without a single punch in or overdub,” Simon recalls. “It was beautiful.”

By that time, Simon had also begun recording his own quirky solo albums. He pulled back from the business when disco and metal surged, and with the advent of click-tracks and Auto-Tune, which he refers to as “terrible stuff.”

Throughout his projects, he has maintained a hands-on approach. “I was never the kind of producer who liked to sit behind glass and say, ‘OK, take one,’” he reflects. “I want to participate. I’m in it for the music.”

This article originally appears in the October/November 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.