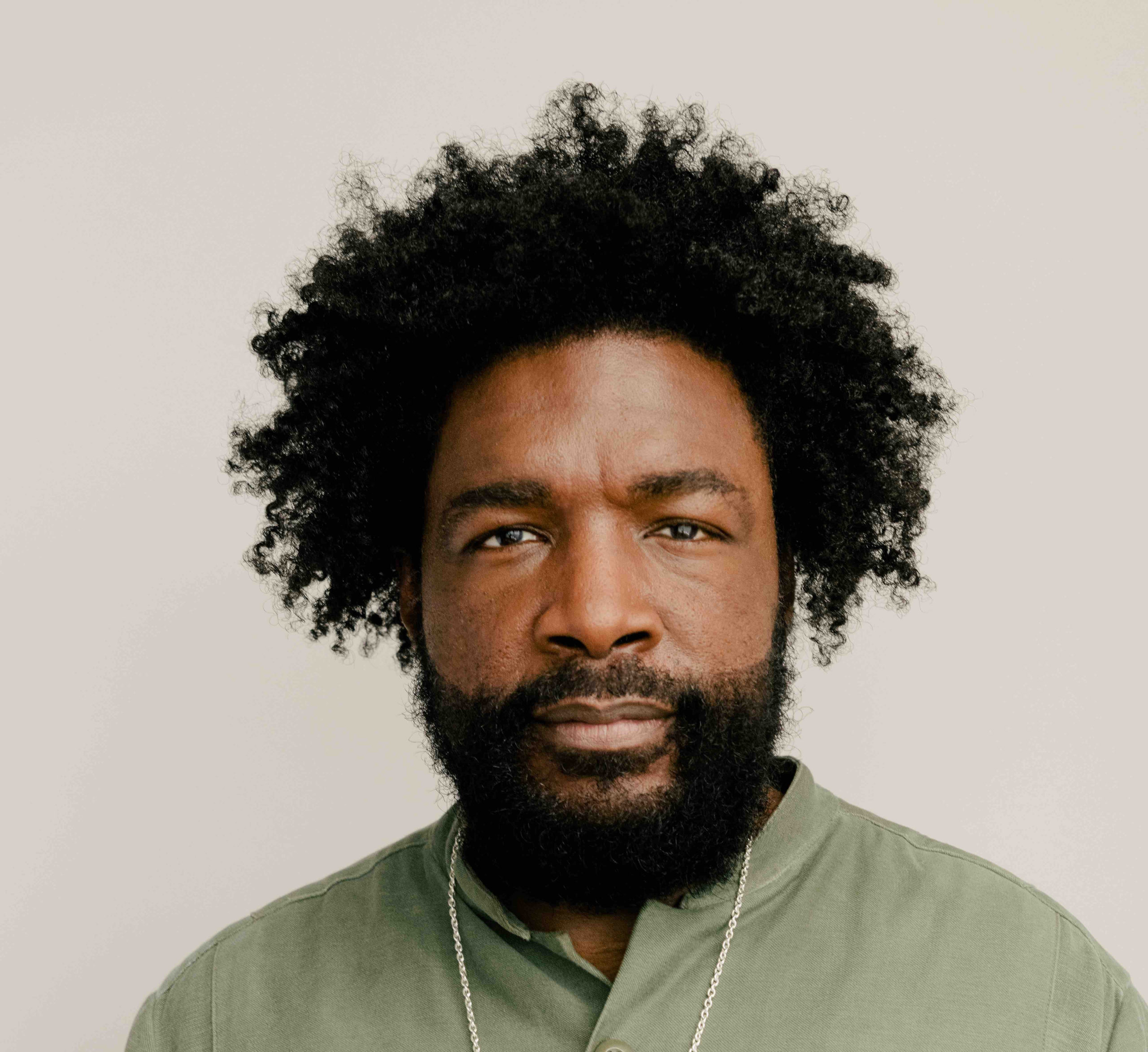

Questlove: The Soul of Summer

Photo credit: Daniel Dorsa

In honor of director Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson’s Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) winning the Oscar for Best Documentary feature, we revisit our June cover story…

***

Relix Publisher Peter Shapiro and Editor-in-Chief Dean Budnick speak with The Roots’ Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson about his directorial debut: a Sundance award-winning documentary that rediscovers an extraordinary cultural event nearly lost to history.

**

Questlove had his doubts.

Film producers had approached The Roots drummer and musical director for The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon about the possibility of directing a documentary drawn from previously unreleased footage of the Harlem Cultural Festival. Taking place over six weekends in July and August of 1969, the event featured performances from numerous artists at the peak of their musical powers, including Sly & The Family Stone, Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, the Staple Singers, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King, the 5th Dimension and Gladys Knight & the Pips.

Yet, despite being a self-described music nerd, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson had never heard of the Harlem Cultural Festival, which was later dubbed Black Woodstock by TV producer Hal Tulchin in an ill-fated attempt to generate interest in the 50 reels of tape moldering in his basement.

After Tulchin passed away in 2017, fears regarding the deterioration of the footage resulted in a renewed push for an intrepid filmmaker to take command, which is how Questlove came to receive the pitch—even if he had yet to direct a project. However, he was not immediately receptive.

“When this was initially presented to me, I might’ve been a little bit arrogant, a little bit cocky,” he acknowledges. “I was like, ‘I know everything that happened in music and there’s no way you’re going to tell me that some random concert featuring Sly, Stevie, B.B. King, the Staple Singers and Nina Simone happened and I don’t know about it.’ So when they presented me with the idea, I just thought that they were just trying to finesse their way to get some tickets to The Tonight Show.”

But, he soon discovered that both the festival and the offer to direct a documentary on it were in fact real. Maybe a bit too real at first—although Questlove is a best-selling author, podcaster and multi-media presence, he had yet to direct a film and he began to experience doubts about whether he could deliver.

“I thought we’d never see those guys again but, when they came back the next week, my heart dropped,” he says. “It was like, ‘Wait a minute, they weren’t lying. It’s all true.’ That’s when I went the opposite way, which was like, ‘I just got my permit, why do you want me to drive this 18-wheeler?’ So at the very beginning, I was like, ‘I don’t know if I’m the guy to do this.’ They had to convince me and say, ‘Dude, this is the moment you’ve been waiting for. You write books, you curate shows, you know music, you’ve studied this your whole life and now you get to apply everything that you know about music into this project. You can do it.’

“I kind of thought that I had to sing for my supper,” he continues. “At the time, I was teaching at NYU, but I didn’t go to NYU film school. I was like, ‘How do I do this?’ Working with the guys at Radical [Media], especially my producer Joseph Patel, is the greatest learning experience I’ve ever had, as far as going into a place of creativity that I wasn’t as familiar with as a drummer or DJ. But I realized that this movie was really a chance for me to take my own advice. There was the irony of me of writing a book about creativity, and then being near-paralyzed and panic-stricken about going into new territory.”

As it turned out, the neophyte survived and thrived. The documentary Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) premiered at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, where it won both the Grand Jury Prize and Audience Award. Searchlight Pictures acquired it for theatrical release, and it also will stream on Hulu.

When asked whether he’s become infatuated with the filmmaking process, Questlove responds, “I hope so. I’ve got four more projects down the line. We’re currently at the beginning of a Sly & The Family Stone film, and there are three other projects that we will announce. I was a guy that would always say, ‘Someone needs to make a film about a particular subject because I really want to see how it happened.’ And now I’m that person. So I’m happy to be in this position.”

Watching Summer of Soul, the whole vibe and the relationship between the artists and the audience feels like a hippie festival today or Woodstock back then.

When I show the film to younger people, I explain that the legend of Woodstock really came to prominence after the movie came out. There’s a great story in Prince’s autobiography in which he talks about one of the nicer times that he had with his dad, which was when his dad took him to see Woodstock at the age of 11. That really changed his life growing up. So for me, one of the burning questions I had was whether this film would have had the same effect if it had been allowed to develop and if it received a nationwide release back at the time when Hal Tulchin was trying to shop it. A big part of the narrative is the fact that, for 25 years, he kept trying to sell and get people excited about this film, but they were just sort of like, “Ehh.”

He was the one who came up with the name Black Woodstock, hoping that might help?

His last minute attempt to get people excited was to tell everyone: “This is Black Woodstock!” But people were still like, “Nah.”

Do you think that characterizing the event as Black Woodstock hurt the prospects in certain respects?

The way that he did it was sort of like a last-minute Hail Mary attempt. When I first got the film, I was immediately like, “We’re going to call this Black Woodstock.” That’s how it’s come to be known. However, in the final stage of editing, I thought, “Man, it is really doing a disservice to this film to contextualize it that way and to paint it as the Cinderella step-sister or Rudolph who didn’t get to play any reindeer games. This will forever put a stain on it when it could otherwise be its own thing.”

So in the last two months, I called a meeting with everyone and I was like, “I don’t think this film is Black Woodstock. I think it’s its own thing.” I’m really glad that we made that decision because, at the time, it was a passion project for me and I didn’t think that it would really garner that much attention, especially because we were in a pandemic. I was just like, “Well, maybe, if anything, this will take people’s minds off of panicking for two hours.” But I surely didn’t think that this was going to be received the way that it’s been received. So I’m really glad that we made that decision to not call it Black Woodstock.

The footage has a vibrancy that is all the more impressive when one realizes it’s 50 years old. The yellows and oranges really pop and leave a lasting impression. Can you talk about how you approached that?

We were so fortunate. Once we finally took those tapes, there were like 50- plus reels in the basement, but we found out that there were only two people in the United States we knew of who actually had the technical capabilities to play the reels back to us. There was also the process of baking the film and then brushing off the dust and all those things—restoring it without destroying it or scratching it. That took about five months, which was actually a good thing because, during that time, I was able to live with some of the footage.

The very last time that Hal Tulchin attempted to make this happen—either on the 20th or the 25th anniversary, he tried to do it as an indie or that sort of thing—he transferred a good part of the footage to video cassette. This was about 20 hours worth of footage and I kept that rolling 24 hours a day in my house. I called it my aquarium. I kept it rolling on every monitor—in the bathroom, my bedroom, the living room. When I was out or in the studio, it was on my laptop. I wanted to really live with it so that I didn’t miss anything but I also wanted it to be natural. I didn’t want to just take all the footage and then carve out the hours to sit there and watch it.

So once I had the five months on my hand, I just lived with it and kept taking notes—“This part’s interesting and I also like that part.” So I felt I was ready once the footage came back.

Once it did, the footage was flawless. That’s the one thing I wish I could take credit for, but no one was more shocked than we were about how little work we had to do.

As far as the look, there was a discussion about whether or not we should transfer it to film so that it would come off looking more like a 35-millimeter film instead of a sort of primitive 1969 video thing. But it felt more natural in the state that it was in. So we didn’t try to do anything like stretch the film out or any of those things. It was as if you were watching it on television in ‘69.

The audio is equally impressive. Did that require a lot of work?

Now that is one of the biggest mysteries ever because I come from a band that uses 76 outputs. My top snare is miked, my bottom snare is miked and so are my second snare, my toms and my bottom toms. But when we went through Hal Tulchin’s notes, I was baffled to discover that they only used 12 microphones. I’m amazed that they were able to get that sort of clarity and snap. The best sonic example of that was when we were mixing B.B. King in 5.0 and the Dolby stuff. It was as if you were sitting onstage listening to it in real-time.

So what you’re hearing is basically the flat board mix. We gave these audio reels to Jimmy Douglass, who didn’t enhance it. He just did a little sweetening. Of course, he was kind of a wish-list name. He’s an engineer who has done so many classic soul records. He was 17 when he first started with Barry White and rose to prominence mixing a bunch of classic soul records in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Then he took it a step higher, working with Timbaland and Missy Elliott in the ‘90s and the early ‘00s. He engineered the Amazing Grace movie with Aretha Franklin, and I felt like he got exactly what we wanted to achieve sonically.

Who ran the mix at the shows?

There was a list of the staff but it didn’t specify who did that. In watching the raw footage, though, I will tell you that the way they achieved it was something else. I’ve never seen such precise, absolute thoroughness with such little technology. Each act had to sort of do a soundcheck before they performed. On the raw footage, you can watch them set up for Edwin Hawkins. They were trying to figure out how to perfectly place the microphones so you get the full gist of what the choir was going for. It was a miracle; it was a complete miracle.

One of the things I discovered was that the camera guys and the sound people were available for all of the performances except for one. So the way they organized the festival, they decided to make the last show the “throwaway show” that wasn’t documented. It was the Miss Harlem beauty pageant—a local New York band that I later found out was an 18-year-old Luther Vandross’ first band performed that day. Unfortunately, that performance wound up on the ground. But I later found out that the sound people and the video people couldn’t make that show because they had to shoot the pilot episode of an unknown show on PBS called Sesame Street. We lost the last day of footage because Sesame Street was just starting.

These were shot on Sunday afternoons. Did everyone just come in that morning and soundcheck that day?

That’s the way that the story is told to me. Some of it was videotaped, a lot of it was documented on camera, and it was in Al’s notes. I also wondered, “Did the act come onstage to soundcheck in front of the audience?” I hate when we have to linecheck or soundcheck in front of the audience that we’re about to play in front of and someone’s like, “Play a song.” My feeling is that the audience is watching us—I don’t want to give a song away.

But to them, it wasn’t about, “We’re throwing a concert.” It was always, “We’re shooting a television special.” In watching the Edwin Hawkins linecheck, they would ust kind of just ignore that 30-50,000 people were watching them and they would just linecheck and someone would explain to the audience: “OK, this is for television. So put your best face on in five, four, three, two, one.” To them, it was like watching a television show, not a concert.

If you’re a creative person and you have an opportunity to try something new, you lean into it. Tony Lawrence was someone like that. Not only was he the promoter but he was also the host and he performed at the festival as well. Can you talk about him?

He was a special individual. One of the humorous, yet frustrating aspects of the film were the many “close, but no cigar” moments of trying to figure out Tony Lawrence’s life. We found the people that surrounded him and there was a paper trail up until maybe 1991. But, then we couldn’t find anything because he has such a common name. I even tried to use a private-eye connection but he’s one of the most elusive people ever. He truly went under the radar.

Thank God that at least four of the organizers that were there to assist him were around to help guide us. I mean, just watching him, you have a sense of his power. There’s a point where Sly & The Family Stone starts and it seems like it’s about to get a little rowdy because the kids are excited but he was able to have complete control over that crowd. He was dealing with somewhere between 50-70,000 people per show but, when he said jump, they asked how high. He’s clearly a man of the people and you see the trust that they had in him as a promoter and as a Harlemite. He spoke the language. It’s such a hard position to be a businessman but also one of the people—to shake hands with dignitaries and politicians but also just kick it with the homies on the corner. That’s an amazing skill.

Also, his wardrobe was off the chain. [Laughs.] Hats off to Tony Lawrence, man. I’m so glad that he had the vision to really see that through.

What else did you learn as you began researching the event?

I discovered that one act who wanted to play the festival and got rejected was James Marshall Hendrix. Jimi Hendrix also wanted to play the Harlem Cultural Festival, but they were like, “You’re a little too radical there, Jimi. You might be over the heads of our audience.”

I later found out that Hendrix picked the month of July to get back to his blues roots once he disbanded the Experience and was about to get with the Band of Gypsys. They were playing Harlem nightclubs doing blues sets; he wanted to return to his blues roots because he felt like people thought he was a novelty act or just the guy that sets his guitars on fire. And he wanted to show he was serious about his musicianship. So I really wish that Hendrix had a chance to perform at the Harlem Cultural Festival. That would have meant a lot to him and could have meant something to us.

What makes the festival’s decision not to allow him to appear so funny is that during the Herbie Mann set, Sonny Sharrock takes one of the most atonal, craziest guitar solos I’ve ever seen in my life. It was to the point where it was like, “Oh, this isn’t just loud noise; this is him crying. This is him expressing grief.”

I will say that one of the issues that I wanted to bring forth with the film is that music was often the outlet for mental health for a lot of Black people during that time period. I’m really glad that we got to explain the cathartic nature of how music works with jazz and gospel and those things. So when you’re watching people doing these crazy solos, or singers yelling these loud, primitive noises, it really means something.

Beyond the performances, you also add some cultural context and social history. Was that your intent from the start or did it come together over time?

In the very beginning, I knew what I was up against as far as history is concerned— all the great classics like Wattstax and Soul to Soul. There’s even a When We Were Kings supplement, Soul Power, about the music before the Muhammad Ali fight with George Foreman in 1974. There was actually one more directed by Stan Lathan called Save the Children that I think he’s about to restore and put out next year for its 50th anniversary. But, when we got this project, Aretha Franklin’s Amazing Grace had just come out and I thought it was interesting that Sydney Pollack’s footage was just the concert without any context whatsoever.

I was fine with that but the music nerd in me also wanted to know the stories behind it. So, when I got into a conversation with Bernard Purdie and Chuck Rainey—the rhythm section for Aretha Franklin—they had all these stories, like about how The Rolling Stones parked in James Cleveland’s spot and how he was angry about that and cursing. James was upset that they were tripping over wires, and Aretha was flustered watching her dad come in five minutes late to the thing. There were a lot of stories behind that performance, but I also admired the boldness of just letting the music speak for itself. Initially, I was like, “Alright, let’s just do a straight-up, two[1]hour concert with no context whatsoever.”

After I thought about it, the first thing that I wanted to do was find out if there were any people still alive who could recall memories of it. The risk of doing that is anyone who was under the age of 10 back then—who would be in their mid-50s right now—might have a spotty memory of it and not be too sure of their recollection. Then on the other side, those who were slightly older in their early 20s are now 75-80 years old. And their memories might also be a little spotty. But we found the perfect combination of people who at the time were just getting out of high school—a lot of them were 17, 18, 19— which means they’re now 71, 72, 73.

For me, the game changer was our first interview, which was Musa Jackson. Within 10 minutes, there were already tears in his eyes. And that was instantly the green light—“Oh, we should investigate this further.” He was five years old when he went, so he wasn’t too sure if he remembered stuff, but he told us what he remembered. He said this was his first memory of being on Earth and he accurately described everything, even though we didn’t show him the footage yet. We asked, “What do you know about it?” And he said, “I remember those orange outfits.” And sure enough, we were like, “Wow, he’s spot on for a five year old. He remembers everything.”

And then, when we showed him the footage, it just broke him open because he thought that maybe it was a figment of his imagination. He wasn’t too sure. So when we showed it to him and it just verified his first memory in life, that touched him. Then it was like, “Alright, we’ve really got to open the chamber now and see who else is out there.”

There were so many little tidbits and stories. Probably the funniest story I didn’t share—that wound up on the floor— involved the two women who snuck off to see Sly & The Family Stone and lied to their parents about it. One of them gets home, she commits the perfect crime, goes to bed and her mom happens to watch the 11 p.m. news. And who’s in the front row losing her mind at the concert but her daughter? [Laughs.]

For me, there’s a historical context, but there’s also this stuff that I wanted to know as a music nerd and as a working musician. I wanted to know if there was such a thing as a rider back in ‘69. Did you have a cheese spread? What was your backstage like—were there couches? And were there hotel accommodations? I wanted to investigate all of these things.

So, I got a little bit of both. I got the historical context and then I got Gladys Knight talking about how they had to rehearse five hours a day and those sorts of things. So there’s an embarrassment of riches; there’s over 40 hours of footage, music and stories from the participants.

When I come in the door—the same way I do with music and other projects—I leave no stone unturned. At first, I thought about including three performances from each act, but that would have been a lot. My first cut was close to the three hours and 20 minutes. So there was a lot of magic I had to leave on the floor. But the experience of editing this film is something I’m going to apply to my music and everything else I do.

As a band leader, music director and someone who does all the other things you do, it seems like you’ve been in training to direct this film for many years now.

I’ve come to realize that, at the end of the day, it’s not about whether I’m a drummer or an author or a food advocate. I think creativity is the umbrella and there’s just different facets under it. I think there’s creativity in sports. I also learned three years ago that there’s even creativity in the medical field because I had to give these speeches at hospital facilities. And I was like, “Wait a minute. What does creativity have to do with the hospital industry?” And they’re like, “With anything that requires experiments and trial and error, there’s creativity.” I feel like I’m sort of a real life, living example of discovering what’s under the umbrella of creativity.

Thinking back on the music in this film and of that era, is there another band that you would have liked to be the drummer for other than The Roots?

You know, it’s weird, having talked to all the members of The JB’s, they each convinced me: “Trust me, Ahmir. It is better for you to have watched it in hindsight than for you to have lived it in real-time. We had to endure 14-hour bus rides and countless rehearsals so that you can have enjoyment in your life 20 years later with James Brown.” I will say that, of all the ‘70s collectives, I would have enjoyed a run with Earth Wind & Fire because of where they were going with their theatrics and mysticism. They were using Doug Henning in ‘74, levitating in concert and doing all these magic things that would lead to P-Funk with the theatrics and whatnot. That probably that would be my dream assignment.

The film ends with Musa Jackson’s earnest reflection: “How beautiful it was.” That also could have been an apt name for the documentary. As you began cutting the film, did you always slot his remarks in that spot or did you add them later?

Musa was my very first interview. Then after the interview was over, we were just casually talking. But I’m glad they kept the cameras running because, by that point, it was like, “Alright, well, thank you very much.” And he was like, “I’ve got to sit here and process that. You guys don’t understand—you just showed me my childhood.” So that definitely could have been our title. We went through everything from A Sea of Blackness to Soul 69. We went through every title, but Summer of Soul really just stuck out to me.

When it comes to the ending of the film, when we started the process, I begged everyone for rigorous honesty. I told them: “This is my first film. I don’t want to be embarrassed. I don’t want you guys to be like, ‘Oh, that’s great, Ahmir,’ and then it’s not great.” So anytime that there was anything close to a cliché or amateur hour, I absolutely begged them: “Please let me know. Don’t let me walk out of this house with a mustard stain on my shirt without telling me.”

Initially, when we got to the subject of Black erasure and why was it so easy for this festival to not have any historical context, I wanted to almost Sopranos-end the movie, where it just instantly cuts off, just drops out in the middle of a sentence. And they were like, “OK, we get where you’re going, but you can’t do that. People will get angry at you.” [Laughs.] And so they talked me off that ledge.

But I always knew there were three things that I had to establish. I had to establish a surprising beginning and, hands down, nothing surprised me more than Stevie Wonder on a drum set. I had to find a middle or a climax in the middle, which, initially, I thought was going to be the whole moon-landing sequence. And then, at the end, I thought, “OK, I’ll save the best for last—Mavis versus Mahalia. That’s the showdown we were waiting for.”

When we got more into 2020, once we were in the pandemic, there was a different tone and, suddenly, the Mavis- Mahalia moment felt way better in the middle as kind of a somber stop-your[1]heart moment, than just an ending. And then I felt that the fire of Nina Simone would be more apropos at the end because of where we were politically as a country in 2020. I’m glad we made that decision. My initial ending sort of had it nicely wrapped in a bow, a kind of kumbaya moment with Mavis and Mahalia.

How would you define the legacy of the Harlem Cultural Festival, and do you think that the release of this film might alter that legacy in certain respects?

In hindsight, I wonder if this film could have changed the trajectory of musicianship, especially for the Black community, if it had come out in ‘72 or ‘73. After the initial ‘50s-‘60s migration from the South to the Midwest, a lot of families got factory jobs, got better houses and then they bought their kids instruments to keep them off the street. That’s why Ohio was seen as the funk capital of the U.S. Every funk band of the ‘70s had a similar story of their parents buying them instruments and that sort of thing.

I wonder if this could this have changed a lot of musical lives. I was lucky enough have parents that were cool enough to wake me up at 1 a.m. to watch Midnight Special and Rock Concert and In Concert. Even Soul Train came on at 1 a.m. where I lived in Philly. My parents were that cool, but not everyone was.

I’m also kind of hoping that, maybe 50 years later, things will come back around. The most important lesson to be learned is the way that artists use their voices for activism. That, to me, is something that Black people kind of lost around 1997. Hip-hop was once the voice of the politically active. And it’s almost like there was a point in ‘97 where all that went out the window and there was never a return to it. When the war happened in 2003, I told a publication: “The good thing about us being in these times is that I know the music is going to reflect how people feel. There are going to be protests, so it’s just going to be like it was in 1969.” But it didn’t do that and I was shocked.

I really hope, especially with what America’s been through politically in the last year, that this opens the door. It didn’t happen for Prince at the age of 11, but someone is going to take their kids to see this and it’s going to affect them. Hopefully, it’ll all come full circle.