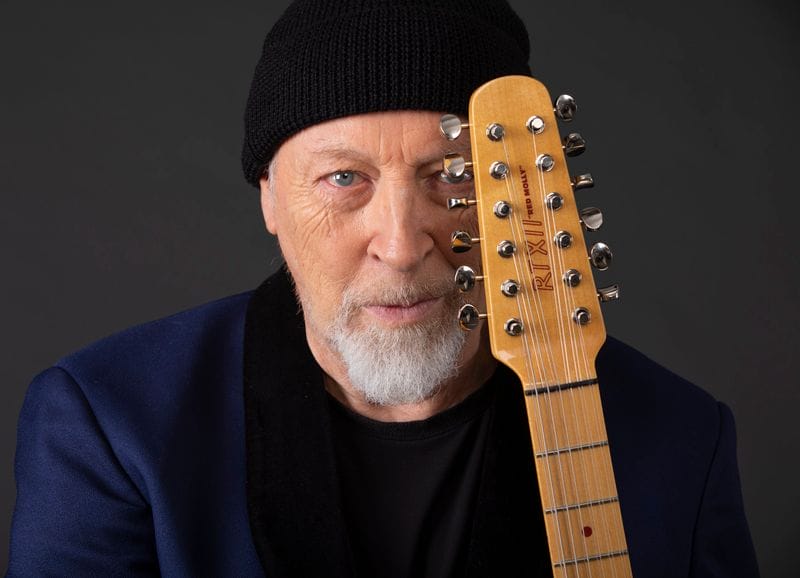

My Page: Richard Thompson “The Ghosts Were There After All”

photo: David Kaptein

***

Ship to Shore, my new album, is named after a chapter in the autobiography of MJ Trevelyan, about his life as a trawler fisherman in Cornwall, from World War II up until his retirement. I am grateful to his widow for access to the unpublished manuscript. He was an extraordinary seaman, but perhaps his reputation on the shore made him an unlikely candidate for a publishing deal. In the aforementioned chapter, he describes the lifeline that communication with the coastguard provided, saving many lives in the unpredictable seas around South East England.

Although my life and Trevelyan’s were profoundly different, I was struck by metaphorical similarities and incidents in his life gave me inspiration to create songs that reflected on my own.

“Singapore Sadie”—This refers to his earlier life in the Merchant Navy and an unrequited affair. The way he describes her, she was probably from a wealthy family that had fallen on hard times.

“Freeze”—Trevelyan was a model captain at sea, but he was notoriously indecisive on land. He bought and sold the parcel of land next to his cottage a total of three times. He once moved to Clovelly, and then he moved back again.

“Life’s a Bloody Show”—Again on land, he could be manipulative, arrogant, drunk and a grifter. You would think he lacked a compassionate bone in his body.

“Turnstile Casanova”—The love of his life, Elsie Banks, was stolen from under his nose by a popular Plymouth Argyle footballer. She then dumped the footballer for a sordid affair with a married TV personality.

“Maybe”—This is another song about Elsie, taking place during Trevelyan’s long pursuit of her.

“The Fear Never Leaves You”— Trevelyan lost half his crew in a terrifying storm in 1952, but, if not for his actions, they would have all perished. The way he wrote about it suggests he suffered from PTSD for many years. His bravery deserved a medal, which he did not receive.

“The Old Pack Mule”—His children treated him like a cash machine, and they couldn’t wait for him to pass away so that they could receive their inheritance. His two sons refused to crew for him after a couple of years, and his daughter moved away to Canada. Reading between the lines, he was not a great success as a father. None of his children survived him.

“Lost in the Crowd”—His first wife, Beersheba, walked out on him after years of abuse. She was always happier when he was on a long fishing trip, so she jumped out of the carriage of the Cornish Riviera Express at Waterloo Station, and even though he pursued her, it was morning rush hour, and he lost her in the press of commuters. She went back to her mother.

“We Roll”—Trevelyan wrote, or at least adapted, a sea shanty of that title, which he sang regularly in the local pubs. I wrote my own song reflecting my own land-bound life on the road.

“Trust”—He trusted absolutely no one on land. He was swindled over an investment in the Cayman Islands, which seemed to sour him against just about everybody. I wrote my song about his dark view of his fellow man, in spite of his upbringing in the Plymouth Brethen. At sea, where trust and teamwork is everything, he was a different animal.

“What’s Left to Lose?” —His despair after another rejection in love. There were many.

“The Day That I Give In”—He was romantically pursued in his 60s by one Mary Slattery, a washerwoman whom he found uniquely unattractive. This was all while he was married to his third (and surviving) wife. She mistook his coldness for religious adherence, apparently. She died of heart failure (or some say a broken heart) after three years of fruitless pursuit.

So much for the songs. I was living in Woodstock N.Y., and thought it would be a fine thing to record locally—not really expecting the ghosts of Dylan and Van Morrison to stop by. I had done some demos with my son Teddy at Applehead Recording, which seemed like an excellent location, so we flew the band in and nailed the tracks in a week. Any studio with goats gets my vote.

Applehead is a big, converted barn, with booths for drums and vocals—although, after a while, we put the drums into the main room and just went for live, the way records were made before multitrack recording. There is a lot to be said for spill—every instrument spilling down every other microphone. It creates a sound that puts you right there in the room. Chris Bittner was our engineer, and the studio had accommodations for Michael Jerome, Taras Prodaniuk and Bobby Eichorn, on drums, bass and guitar respectively. My wife Zara sang harmony and David Mansfield joined us on fiddle.

As has been my practice on the last few albums, I collected talismanic objects in the immediate area of the studio and around town, one for each song. This may sound like meaningless bollocks to others, but it’s a practice that has helped me to focus in on the music. From the Woodstock flea market, I bought an old toy cowboy, a salt shaker and a little pharaoh—or what was left of it—surely not from ancient Egypt. Around the studio, I found a pine cone, a catalpa leaf, a Fender pick and a six-sided die. From where we were staying, I found a field vetch, a clover and a cypress cone. I kept them all in a bag and took them out from time to time to focus on a particular song. Weird old hippie, I hear you cry—well, it works for me. Do I have to tell you which object goes with which song? At the end of recording, I put them on the fire—cleanse the mind, make way for the next record.

We lasted a year in Woodstock. The weather, the constant power cuts, the internet and backup generator failures, it all finally drove us south. And the process of digging my car out of a huge snow drift and a vast ice storm that brought down 400 power lines in the county is what finally convinced us that we were suburbanites. Perhaps the music did capture some of the vibe of a special, artistic place—and the ghosts were there after all.

**

Richard Thompson released his latest set, Ship to Shore, on May 31 via New West Records. The self-produced 12-song album was recorded in Woodstock, N.Y.