Lord Huron: I Am The Cosmos

The title of Lord Huron’s third LP, Vide Noir, is French for “Black Void,” a seemingly bleak image for an album of such immersive color. “Aimless drifting in a far-off place/ Hurtling through the vast unknown,” frontman Ben Schneider sings on opener “Lost in Time and Space,” his falsetto beaming down with a mystical harp glissando. It’s like a movie dream sequence where the frames ripple at the edges, signaling to the audience that they’ve passed into a new realm.

That’s an odd combination—the heavenly and the nihilistic, the cosmic and the divine. But that disorienting sensation reflects the album’s core theme: confronting the unknowable mysteries of existence. “When I consider the realities of the universe, part of me starts to feel a sadness, a loss of meaning,” Schneider says. “But the more you consider it, the more it starts to take on its own beauty—how enormous this universe is. Every living creature you encounter has the same sort of inner landscape that you have. It seems so vast, thinking about the conscious space in this world. It’s kind of remarkable and beautiful, without having to lay on this mythology. As we move away from religious thought into the scientific age, I also feel a lamenting for the loss of that way of thinking because it is so beautiful. It’s creative, really. A lot of it is artwork itself. And it can be beautiful to see people who find that really deep meaning in it. But at the same time, it’s one of those things where, once you know what you feel to be the truth, it can’t be unknown, so you have to come to terms with it—and that’s what staring into the void is about.”

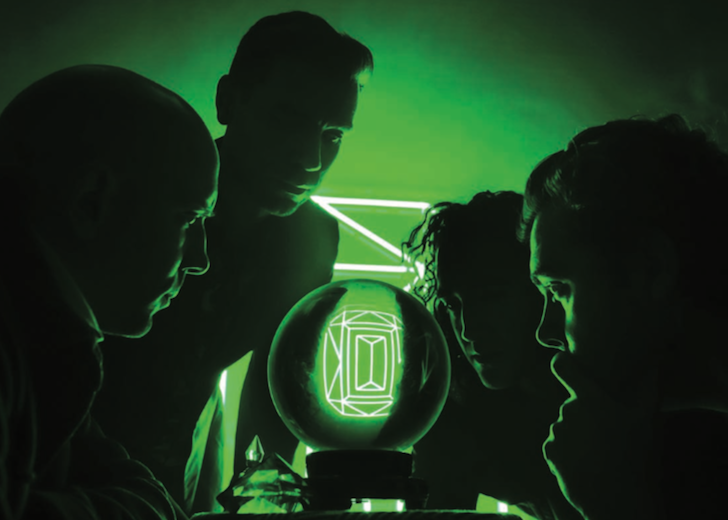

Vide Noir, like Lord Huron’s past work, is a flip- book of impressionistic short stories. But these 12 trippy tunes tap into a more supernatural vibe, with references to fortune tellers (two-part epic “Ancient Names”), mythological gods (“Secret of Life”) and mysterious relics (“The Balancer’s Eye”), among other queries of the world’s hidden secrets.

Schneider started this existential journey alone, late at night, driving around the vast expanses of LA—a city filled with people, but somehow still lonely. On many evenings, he’d take “deep dives” into new music, absorbing new sounds as he drifted aimlessly through the scenery; sometimes he’d let Henry Rollins, and his eclectic KCRW radio show, do the digging for him. Gazing out at the shifting landscapes of water and hills, he found himself in a contemplative mood—and, suddenly, melodies and rhythms and words jumped into his brain.

“It had a lot to do with the geography of LA, the landscapes out here,” he says. “I’ve always been inspired by nature. I know it’s weird to be driving around the city and be inspired by nature, but you’ve got the mountains in the distance, the ocean out to the west, this sprawling grid of lights and hills in the middle, and the stars up above—all of that was merging together. We think of cities as these man-made creations outside of nature, but I started thinking about them as an extension of nature—or our nature now. Seeing that grid of lights merge with the stars in the sky and getting swallowed up in the ocean at the coast, I started thinking about how there are all these incredibly rich stories and a consciousness rolling around this vast galaxy of lights throughout the city and, by extension, the cosmos. It’s funny how your mind can just wander while you’re driving.”

After many of these spaced-out trips, Schneider had amassed enough fragments through his iPhone Voice Memos—from beatboxed grooves to ideas for general “vibes”—to start “jigsawing” songs together back at the band’s studio/rehearsal space/club house, Whispering Pines. This overall process has remained unchanged, dating back to Lord Huron’s debut LP, 2012’s Lonesome Dreams. Schneider wrote and demoed the songs, before bringing in his bandmates—drummer Mark Barry, bassist Miguel Briseño and guitarist Tom Renaud—to flesh out the arrangements. That situation, which allows Schneider to function as their creative vessel, suits everyone involved: “They all trust me to have the vision in the writing, which is hugely beneficial,” Schneider says. “I feel very lucky that they trust me to do that.”

Lord Huron technically originated as the Michigan native’s solo project. In 2010, years after bouncing around from the University of Michigan (where he studied visual art) to France to New York City and LA, he recorded two folky, calypso-inflected EPs and gradually built local buzz. But as his sonic ambition started to swell beyond these modest beginnings, he realized he needed to recruit his childhood friends.

Schneider, Barry and Renaud grew up in the same circle of music-obsessed kids, and they played together in a local band that morphed through ska and punk.

“[It was] the music of the times,” Barry says. “We were decent. We played together all throughout high school and rehearsed in my parents’ basement. But everyone went to college and did their own thing.”

In 2010, Schneider played him the early Lord Huron tracks. “I was living in Nashville at the time, and I said, ‘Why don’t I just drive out there and we start a band?’” Barry recalls. “So I just drove out there and expected to come back to my girlfriend in Nashville, but I ended up staying in LA. I knew I needed a change. I wanted to sink into something, and it was the perfect opportunity. Ben’s always been crazy talented, but I just didn’t recognize it at first. I was like, ‘Dang!’”

After they drafted Renaud and Briseño (whom Barry first met and collaborated with in high school into college), Lord Huron had blossomed into a more expansive ordeal than first expected. And the music followed suit, evolving from the dust-blown, Fleet Foxes- style Americana of Lonesome Dreams to the widescreen, slightly dreamier folk-rock of 2015’s Strange Trails. At this point in their evolution, the progression seemed clear. As their profile grew, so did their budget—along with the grandeur of Schneider’s songwriting. But no one—probably not even Lord Huron themselves, to a certain degree—could have anticipated the kaleidoscopic shift of Vide Noir.

Schneider still considers it a “pretty organic” transformation. “For me, it’s been a mixed blessing with streaming and online music,” he says. “When I was younger, exploring and discovering music was all about going to record stores and getting recommendations from the guys there. And I loved that. I loved the social aspect of it. But you were limited by your budget which—especially back then—could be very limited. But nowadays, exploring music is so much easier. It’s just endless. There’s really no specific genre or person I’ve listened to over the past few years, but just having this expansive universe of music at my fingertips had a lot to do with the variety of sound and the scope of this record. It relates to the theme of the record, too—being adrift in this endless universe, and coming to terms with your smallness. To me, that’s all related to the way the record sounds, too: this vast, psychedelic and sometimes disorienting wash.”

Vide Noir’s scope is jaw-dropping—from a newfound emphasis on groove to the atmospheric mixing of psych-rock legend Dave Fridmann (The Flaming Lips, MGMT) to loads of unexpected instrumentation. Barry even cites the soulful “When the Night Is Over” as their first song that “swings.”

“A lot of that stuff was there from the beginning with the harps and flutes and Mellotrons because those sounds are so evocative,” Schneider says. “They’re such good storytellers because they come with all this evocative imagery that people associate with those sounds. I’ve always been interested in using shorthand with the sounds we use, whether it’s a ‘50s rhythm or a ‘60s guitar sound. It’s amazing how much you can communicate with just the color of a sound. People associate a certain emotion or time in their life with it. You don’t know exactly what you’re going to evoke, but some stuff, like the harp, has this dreamy, celestial quality.

“My wife started playing the harp,” he adds. “She’s a pianist, but she picked up the harp and started practicing it in our house. It’s probably the most pleasant instrument to hear practiced in your home. I’d be napping and hearing these lovely glissandos and chords coming from the other room, so it was kind of in my head when I started to write. It’s nice to have a community of musicians who play all these instruments so you have this grand toolbox.”

Even the song structures are more experimental, like on the two-part—or, truthfully, “five- part”—epic “Ancient Names.”

“I imagined it almost like you’re traveling through different dimensions or places in time as it goes along, like the song is moving through dimensional portals,” Schneider says. “At the beginning, you’re hearing it performed by some kind of fortune-teller’s flutes, and then you pass through a portal to some ‘60s R&B backing band—it’s a little late at night, and they’re getting a little loopy. And then you go through some kind of cosmic electronic interlude with bells, and then you pass through one more portal into a punk club where this band is ripping through the song, and then at the very end, there is some sort of world music group. That goes with what the song is about: being trapped in this feedback loop of time and space.”

But for all its stoner-friendly headphone quirks, Vide Noir is still rooted in human pain, loneliness and loss—the very emotions that pushed Schneider to dream up such philosophical thoughts in the first place. A good example is the pulsating rocker “Never Ever,” which the frontman admits “veers into the paranormal” realm.

“I’ve always been interested in telling good stories but, for me, that always starts with something personal,” he says. “The core of all of it—in order for it to seem authentic and for me to be able to express myself well—has to come from something that happened, whether it’s to me or someone close to me. And from there, I can let it go into fiction—let it spin off into other fictional realms. Just because I think I can explore it more deeply that way, not being tied to reality necessarily. Sometimes, that’s a faster way to get to the truth. I’ve always found that fiction can pack quite a punch, in terms of philosophical truth and bigger truths that are sometimes hard to get at through reality.

“The starting point was having a connection with somebody and feeling like it’s almost too good to be true, and then it sort of ends up being too good to be true—or imaginary,” he continues. “I think it’s something a lot of people have gone through, in one way or another. I wanted to take that universal experience and thrust it into some sort of extreme realm—in this case, something that seems to be verging on the cosmic, supernatural. I’m a believer in science and hard facts and truth in reality but, to me, there’s a real beauty to the sort of spiritual, paranormal stuff that humans invented to explain things—none of which, to be honest, I put any stock in. I’m not a religious person; in practice, I’m not a superstitious person. But there’s a certain utility to that kind of way of thinking. There’s so much truth in human consciousness, kind of wrapped up in myths and legends. I’m interested in trying to unpack that stuff—and maybe even create some new ones.”

This article originally appears in the July/August 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interview, album reviews and more, subscribe here.