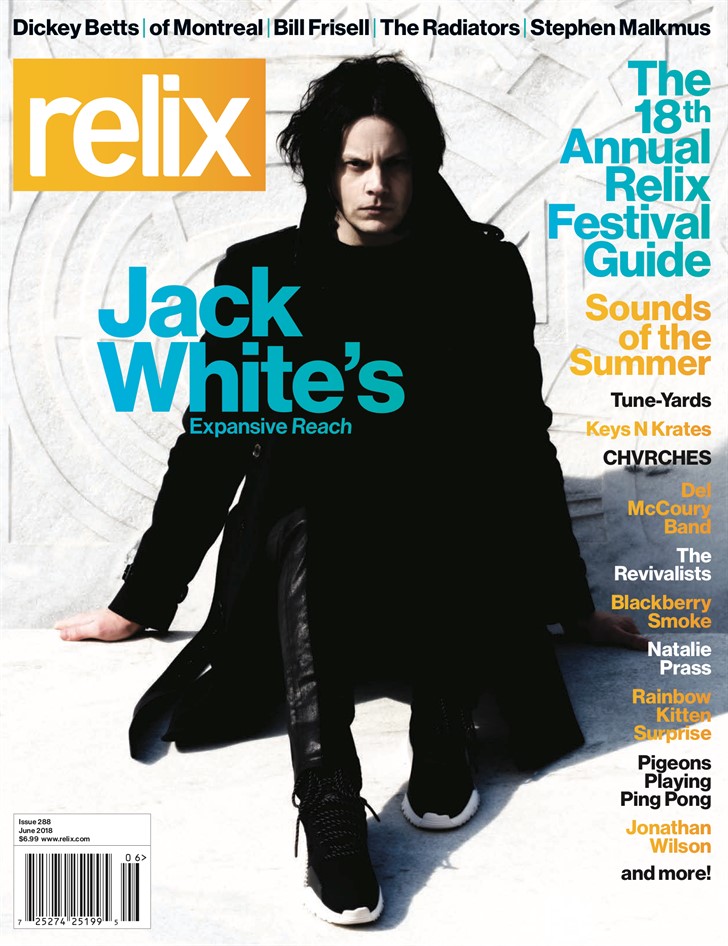

Jack White: All Within Reach

Theon Delgado

This article originally appears as the cover story for the June 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.

Although Jack White is brimming with opinions, there is one subject that renders the otherwise garrulous musician altogether tongue-tied.

When it comes to the topic of recording his vast and varied new album, Boarding House Reach, he balks at inquiries regarding any mirth or merriment he may have experienced during the process.

“A lot of people tell me: ‘Wow, it sure sounds like you had a lot of fun making this record,’ and I just don’t know how to answer that. That’s a word that I’ve really struggled with my whole adult life. I want to say the right thing—‘Yeah, it was a lot of fun.’ But, that really diminishes all that went into it. There are a lot of musicians who worked really hard, a lot of engineers who worked really hard. ‘Fun’ makes it seem like we went to the amusement park.”

“I think ‘fun’ is what Weird Al Yankovic does,” he continues. “That’s not an insult; I like him a lot. What he does is really fun. And I can’t imagine them not laughing when they’re recording. And then on the other side, I’ll see how Captain Beefheart, Frank Zappa and Beck are able to figure out a way to combine humor and music in a way that makes sense. You can hear Captain Beefheart laughing on Trout Mask Replica because he loves the words so much. I laugh at metaphors that mean three different things at once. A while ago, in an interview, I said how, in The White Stripes, Meg and I didn’t high-five each other at the end of a song after we mixed it. It wasn’t like, ‘Wow! We got somewhere; what a blast!’ It was me in a room, with an engineer who wasn’t saying anything and Meg who wasn’t saying anything. I had to think, ‘Where are we going with this and why are we doing it?’ That’s different than a group of four or five guys all kind of getting high and making each other laugh, cracking up and trying to have a blast. I don’t really know if I’ve ever experienced that. Maybe I shouldn’t.”

Indeed, although White grew up Catholic in Detroit, he has plenty of New England Puritan work ethic in him, and that drive proved indispensable during the process of honing the material that became Boarding House Reach. He recorded the album on two coasts using separate teams of adroit, artful players who pushed the music well beyond the two to five minutes that White intended for the final tracks. And, by dint of necessity, he employed Pro Tools for the first time in his recording life in order to shape the results.

White’s protracted digital editing sessions were prompted by the creative freedom he granted to his studio collaborators, most of whom were new to him and originated in the hip-hop and funk worlds, including drummer Louis Cato (Beyoncé, Q-Tip, John Legend), bassists Charlotte Kemp Muhl (The Ghost of a Saber Tooth Tiger) and Neon Phoenix (Kanye West, Herbie Hancock), synthesizer players DJ Harrison and Anthony “Brew” Brewster (Fishbone, The Untouchables), percussionists Bobby Allende (David Byrne, Marc Anthony) and Justin Porée (Ozomatli), and keyboardists Quincy McCrary (Unknown Mortal Orchestra, Pitbull) and Neal Evans (Soulive, Lettuce).

Evans is the member of this estimable roster who is likely most familiar to Relix readers and, as White explains, “Neal brought a great feel to the recordings we did in New York—lots of energy and funk in his playing. I wish I could take everyone who recorded the songs on tour, but I figured it might be interesting to see what Neal could come up with onstage along with Quincy McCrary. They have different styles, but both are so soulful.”

His touring band, which also includes bassist Dominic Davis and drummer Carla Azar, will be able to experience those halcyon days before cell phones began to vie for the audience’s attention. White has requested that concertgoers place their phones in Yondr pouches during the performances to enable him to better read the crowd while delivering his fully improvised setlists. “Maybe this will catch on,” he suggests. “So far, it seems like it’s really working for the best. I just played in Brooklyn and I haven’t seen a louder, more engaged New York crowd in 12 years. So that’s pretty cool.”

So much of what you do is purposeful, yet we live in an age in which precision is in short order. People will make a statement, irrespective of the facts, and then modify that later with a tweet, sometimes contradicting their initial thought altogether. Do you find this baffling or disheartening?

One thing that I’m always looking for when I read about other artists is some kind of methodology about how they’re doing what they’re doing. I would say 95 percent of the music that’s made out there—popular music and music with a big label behind it—has the same story. An artist goes into an expensive studio, records on a computer, and involves the best writers and producers in order to try to make a hit record. There’s nothing that interesting about that.

It’s not like going after a certain sound with a certain type of mechanical instrumentation, recording devices, microphones, environment, economic constraints or anything like that. I almost never hear stories about the methodology. It’s probably because people are afraid to be pretentious on one side and, on the other side, it just doesn’t matter to them. They don’t care how it’s done; they just want it to sound good. They’re putting themselves in the hands of people who care about how to record and how to set up a microphone, and a lot of those people want to play with whatever the brand-new toy is. If it was 1983, then they’d be playing with gated reverbs, Eventide harmonizers and things that were the hot, new toys at that time. Now, it’s whatever the latest plug-in is for Pro Tools, which is usually an emulation of something that really exists—like a fake reverb emulator to imitate actual reverb in real life.

I wish there were more people who had some sort of methodology, at least for my sake. I just want to care about how it’s happening. Bob Dylan is one of the few who uses methodology whenever he works on something. The thing people misinterpret about what I’m trying to do is that I never put any thought into what kind of music I’m going to write or record. I focus on the methodology, which is the environment and the means to get there—the equipment and the people and the room.

For myself, it would be a mistake to say, “We’re going to record a country song today.” That’s not my goal. A pop singer will go in and say, “We need to write a hit song because I’m a pop singer and people wanna hear hit songs, so we’ve got to figure out how to get there.” They’ll hire a team of songwriters, hire the hottest producer, spend the right amount of money and go into the best studio. For me, the sound of the song and the type of song it’s gonna be are not my goals, which is probably why, on my albums, every song takes on a completely different character than the last song. I don’t begin by saying, “I’m going to make a punk-rock record” or “I’m gonna make a soul, R&B record.” I just set up the scenario like, “This is how many days we’re doing it, this is who’s gonna be here, this is the environment, this is how much money we’re gonna spend, these are the microphones we’re gonna use and then whatever happens, happens. The music becomes real for me under those circumstances.

How important do you think it is for the listener to comprehend the context in which you are creating your music?

That’s been an interesting dilemma for me over the years. It’s also a modern scenario. If you loved a movie in the ‘70s that had an amazing train wreck in it, you would talk with other film lovers about how they did that train wreck, how they positioned the cameras, how they made it look realistic, how they made this horse or man fall off a cliff, and what they did to make something happen. Now, if you see something amazing on screen, the answer is simple: It was done on a computer, end of conversation.

I used to think that if I’m doing something, at least I want to be able to say, “Here’s how it was done and here’s how we got there.” Then, I’d be able to defend it by saying, “We used a ribbon microphone and we used this kind of compressor into a tape machine onto analog tape, and we edited it with an actual razor blade. We didn’t use any computers or any Photoshop or CGI.” I used to think that people thought that was very important. Over the years, I’ve learned that it’s mostly the people in my environment who think that stuff is interesting: engineers, at times other musicians and people like you who care about music.

While a lot of the fans going back to the ‘60s-‘70s and even all the way through ‘90s would care how something was done, the modern teenager doesn’t care what is making any of those sounds on the new Cardi B song. I don’t blame them for that—why should they care? If they like the song, they like the song. If they’re watching some superhero movie the night before, then why should they care what program went into making that spaceship explode? When I was a teenager, I definitely cared where things were coming from because I liked so much about music and, also, because I was learning how to record.

Although, to present the perspective you would normally offer, doesn’t that add richness and nuance, allowing someone to connect on another level?

Oh, of course. If it’s my teenage son, I want to explain all that to him—“Here’s how The Beatles got that drum sound. They used this Fairchild compressor, they put damping on the cymbals to get that tone.” But, if I didn’t say that to my son, who would? If he doesn’t really love music in an in-depth way, will he seek it out? I don’t know. It’s hard to say.

When I say these things, I sometimes think people believe I’m preaching to them about the way they should enjoy music. People should enjoy music however they want to enjoy it.

Another thing happens when I start talking about the historical side of music too much, like I have many times: It makes people think that you’re trying to emulate a Charlie Patton or Robert Johnson or Howlin’ Wolf recording that you heard once. I remember when The Raconteurs played in Detroit, my hometown, someone told me that a friend in the crowd had said, “For a guy who loves The Stooges so much, I don’t understand why this band sounds nothing like them.” And it was like, “OK, so if I say in interviews that I love The Stooges, then somehow that means everything I’m writing is supposed to sound like The Stooges?” Sometimes I think that maybe I shouldn’t say stuff like that because then I’ll have to answer for it and people will think I’m failing at what I’m trying to accomplish. [Laughs.]

But I definitely agree that the nuances, and the how and where are interesting. If a song is beautiful, I want to know, “Well, who wrote it? How did they record it? Where did they record it?” Whenever you go into a studio, they’ll say, “This was the board they used on Pet Sounds” or “I bought this compressor from Olympic Studios and all the early Yardbirds stuff was done on this. You’ll hear stories like that from every engineer in every studio—almost proof that this is a good piece of equipment.

Theon Delgado

Theon Delgado

I always think it’s a mitzvah to at least give people the opportunity to absorb these details.

Oh, man! Are you kidding me? I’ve been spending my whole adult life doing that. At Third Man Records [White’s record store/label], basically everything we do is to try and expose people to the beauty of this side of things. I’m trying to sound realistic, not negative. If a teenager comes into Third Man and buys a blues record and asks, “What was Paramount Records?” or “Who is Blind Willie McTell?” any one of us who works there will sit down for an hour to discuss that. But if you’re asking why they should care, that’s a whole other dark, depressing thought [Laughs.]

All of this is related to something that I think about all the time, which is whether it’s worth putting out records for the public. Is it worth the energy? Is it worth the long hours and maybe even the negativity that comes along with every aspect of all that work? It also means sitting in mud-covered festivals in the Netherlands, or on long plane rides away from your children. And the idea of who people think you are and what you’re allowed to do musically and artistically—all the baggage that comes along with all that.

What do people expect from you and what will they allow you to get away with? You have to be sneaky at times if you want to get past everybody else’s sensors. But this time, I was pretty blatant: Here is how this song sounds, and this is how my voice sounds and this is all it’s gonna be. That’s it. You either love it or hate it. This album is much more divisive than I thought it was going to be. That, to me, is really pleasing because it reminds me of all these conversations I had throughout the years with other people who love music and who are musicians and writers—talking about the merits of a certain album in coffeehouses or bars, and talking about certain songs, albums or bands. It’s great to hear people discussing a record like what I’ve just put out and discussing the pros and cons of it. I’m really glad about that.

I haven’t really read about a divisive record in a while, so I’m glad that those conversations are happening. That’s why I’m a huge supporter of those brick-and-mortar record stores and vinyl records. The vinyl is really the MacGuffin; it’s the format that makes more sense for us all to circle around. But the real point is for the appreciation of art and music, and for the conversations that come out of it. Those record stores were the meccas for those conversations to occur. You walk in and say, “I wanna buy a Led Zeppelin record,” and then maybe someone behind the counter would say, “If you like that, you need to check out this Sonny Boy Williamson song, and you need to check out this Willie Dixon record.” And if you’re smart enough to do that, then you’re on your way to a lifetime of fulfillment.

Jumping back to Pro Tools, did you agonize over the decision to utilize that on this record?

I had recorded in New York with a group of musicians and then in LA with another group of musicians. So when I got back to Nashville, a lot of these songs were 20-30 minutes long and they had 16-18 tracks of music. Now, for most modern recordings, that’s absolutely nothing but, for me, it’s a lot. I usually record on 8-track. For example, Revolver was recorded on a four track—16 tracks involves way too many opportunities and choices that I don’t even want to be involved in.

So I was in a conundrum of how to edit this stuff down and the only way to really do it was on Pro Tools. Now, in Pro Tools’ defense, I think it’s brilliant as an editing tool. I’ve never liked the sound of digital recording—the tone of it, the plug-ins, the emulations, the fake reverbs, and the fake compressors and stuff. That’s not to say that anyone can’t use it and make something good-sounding out of it, but I’ve just never been able to.

I’ve directed videos and short pieces that I’ve edited on Final Cut Pro and said, “Hey, let’s cut the frame right there and then let’s change this to infrared-looking black and white.” Or, I’ll think, “What does it look like if you do this, if you add this solarization?” You can look at it for one second and see if you like it. Back in the days of film, it would’ve taken days to have someone process the film and edit it with scissors and tape, and then you might see it and say, “Nah, I don’t like it. It doesn’t look right.” Now, you can look at it in two seconds and see if you even like that idea. That’s really nice. I think for editing, computers are incredible.

This is your first album since 2014’s Lazaretto. Was there a specific moment you decided to go back in the studio?

I had been thinking that, for a couple years, I’d just spend time with my kids. The only thing I had done was rent an apartment and set up some equipment so, whenever I wanted, I could just go there and be by myself with no distractions and write. But I didn’t have a time frame in mind for that. I just thought, “Well, that’s a scenario. I’ll go there once in a while and work on music by myself and use a couple of different methods, then we’ll see what happens. Maybe it’ll be something interesting.”

I had no time frame where I had an album set to come out, and I wasn’t booking shows. I turned down festivals and all kinds of offers for two or three years because I didn’t really have it in mind. But as 12-13 songs started to pile up, I thought, “I think it might be time for me to go into my studio in Nashville and see if it makes sense to make larger versions of these songs.”

When you brought those songs to New York, were they relatively spare when you presented them to the players?

Most of them were really light—just a couple of notes or a drumbeat or a drum loop I’d have them play along with. I would record a drum loop in Nashville, play it for them and say, “Here’s the melody,” or the riff, and I’d see what happens. Then, I would take that same recording to LA and have a whole new group of musicians play on top of what we just did and add even more to it. So some of these songs have three or four drummers on them, or three or four pianos or keys, and just a lot of choices. I would say this album was mostly an editing scenario. The writing was very fast, in a lot of cases.

The musicianship was outstanding—all these musicians’ energy was incredible because nobody knew each other. We were all strangers so everyone’s got this great energy in the room—electricity—trying to impress one another, trying to add something cool. They know that we’re not there for long, so we better hurry up and figure something out quickly. So we got that great energy on tape and then I spent months editing it, almost like someone editing a film.

Not every method always works for me. You try different things out—“Over and Over and Over” had a complete structure to it because the song was so old. I had recorded it so many times and it never worked out. I had that song mapped out already—this verse, this chorus, this change, these notes. It was just a matter of: “Can we capture the right energy and sound and tones on tape that really bring it to life?” I’d failed at that many times but we finally got it.

Then, with “Corporation,” I had a drum loop and I gave them the riff, they played along with it and I didn’t tell them to do anything. They just did whatever they wanted to do and we jammed for 20-30 minutes. Then, it becomes a question of: “Man, there’s so many good sections where somebody would play some amazing clavinet solo or some really cool bassline.” And you have to figure out how to edit them all down and make them work together. I would love to release the 20-minute versions of these songs one day because they’re so cool. But it was a matter of trying to get it down to a palatable time frame. One thing I knew was I didn’t want to make a double album. I wanted to make a single album, so a lot of these songs had to be cut way down to three or four minutes—something that made sense for a single album.

Your work is often aggressively dissected by fans and music critics alike. Do you ever find that you give away too much of yourself in a song?

I honestly don’t. There are definitely times when, if you are a certain person in my life, you would probably know what incident I was referring to, but I’m definitely not writing about “this happened to me,” in that Taylor Swift kind of way—where it’s like this is about my boyfriend so hear me out. I also don’t really feel too much catharsis, in that sense. That’s one type of artist, one type of fantasy, where the artist paints a painting about something that happened in their lifetime. But there’s a lot of ground out there to write about characters that aren’t you and characters that don’t exist.

I’ve even gone back and changed pronouns in a song and turned she’s to he’s and he’s to she’s just because I don’t want to deal with the aftermath of people thinking that it’s about something in particular. That’s a shame because you shouldn’t have to do that. But, then again, when The White Stripes covered Dolly Parton’s “Jolene,” I didn’t change the pronouns because I was trying to prove a point that we weren’t being ironic by singing this song; we weren’t trying to be funny and the song was important. It was trying to get to a deeper part of our own band by playing this song as heavy as possible.

Dean Budnick

Dean Budnick

Do you remember the first song you ever wrote? What was your intention?

When I was a kid, all I cared about was the drums. There were guitars at my house that my brothers had and I had written this little bluesy thing. I thought that it was me imitating some blues song that was already out there, or that I had heard somewhere but now, when I look back I’m like, “No, that was the first song I wrote.” I didn’t write lyrics for it, and I actually constructed it in a 1-4-5 sort of blues progression, which was funny. I taught myself how to play, and I didn’t know anything and I didn’t really care. But nowadays, if my son did that, I would have been like, “Whoa! What was that you just played?!” That didn’t happen around me; there’s so much stuff going on when you’re part of a big family. You don’t even notice that somebody right next to you is building a thermonuclear device.

I was forced into playing guitar by proxy. I didn’t have a band where we were a group of teenagers and we would all get together. So when I got a four-track in my room and I just wanted to play drums, I would record a guitar part just so I could play along to Fugazi or “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” Bob Dylan, old folk songs or something I wrote myself. At the upholstery shop that I worked at, Brian Muldoon, the guy that I was apprenticing for, played drums just like me. In order for us to play together, I said, “I guess I’ll play guitar.” Up until The White Stripes, I considered myself a drummer and only played guitar because I didn’t have a band to play drums for. That’s when I realized I’d been writing songs and that I could reach people a lot easier with that instrument than with the drums.

You mentioned Captain Beefheart. Third Man Records is rereleasing Trout Mask Replica at the same time that your new album is coming out. Did some of that spirit animate Boarding House Reach, which is similarly wide-ranging?

There’s definitely some amazing timing going on there, which is pretty hilarious. Just when we announced the record, Ben Blackwell at Third Man said he had talked to the Zappa family and worked out a deal for Trout Mask Replica. It’s one of the greatest records ever made. It’s like we’re putting out The Beatles’ “The White Album” or Benny Goodman’s Live at Carnegie Hall. So when we did this vault package with my new record, it was funny that the next time we were gonna make an announcement was on April Fool’s Day, which was also Easter Sunday, and the day that Beefheart and the Magic Band went down to the studio to listen to that record for the first time. I was like, “Oh, my god, that is just cosmically perfect; this is crazy.” It just coincidentally worked like that.

As far as Trout Mask Replica, I came to that from this band I was in, The Go. John Krautner was the other guitar player in the band and he was big Zappa fan and, by process, I became a big Beefheart fan. He told me about Beefheart and I always thought that name just sounded like some goofball. I never paid it any mind, never heard any of his music. But he brought that John Peel Beefheart documentary [The Artist Formerly Known as Captain Beefheart] over to my house on VHS tape and I just lost it, man. I couldn’t believe what I’d been missing for years. I was 23-24 by then and that just opened up a whole new realm. “Moonlight on Vermont” and “Ella Guru”—I just couldn’t believe the process, the way that album was made, the conditions it was made under. That’s some methodology—it is just absolutely incredible. It definitely borders on abuse, really. And that gets into a whole realm of Phil Spector’s firing- a-gun way of working or James Brown fining musicians $50 for missing a note. It’s definitely pleasing to read about that and wonder what it would have been like to be a musician working on a project like that along with people like James Brown or Beefheart. But it gets into a kind of realm where I’ve never gone, so far. [Laughs.]

This article originally appears as the cover story for the June 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.