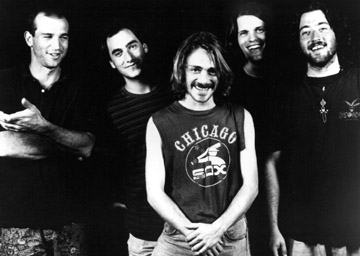

God Street Wine: Seeing Red (Relix Revisited)

God Street Wine will reunite next month at San Rafael, CA’s Terrapin Crossroads on January 21, 25 and 26. The group will open each night with a set of GSW songs, and then the members of GSW will join Lesh, Furthur guitarist John Kadlecik and Furthur keyboardist Jeff Chimenti. Looking ahead (and looking back), we revisit this Relix feature on the band’s efforts in the mid-1990s.

From the outside, God Street Wine’s seven-bedroom white house on seven wooded acres in Ossining, New York looks like any other country house. On the inside, though, it has been transformed into a 52-track recording studio, complete with white baby grand piano wired for sound. Having gone all the way to Memphis to record its first major label release, $1.99 Romances (Geffen), God Street Wine has decided to record its next project a little closer to home. In fact, the band is recording it at home.

The site of the sessions is not the only difference between this project and God Street Wine’s previous recording efforts. The band is producing this one themselves, with a little help from Malcolm Springer, who engineered the $1.99 Romances’ sessions. This time, the band is writing new songs as it records, rather than determining them in advance and working them out for months on the road. GSW also plans to record one song at a time, from start to finish, instead of recording via the usual studio method of basic rhythm tracks, lead vocals, overdubbed leads and harmony vocals.

The idea is to make this project more relaxed than the Geffen effort. “We’re going to try to just have it really open, which we haven’t really been in our recordings till now,” says God Street Wine’s drummer, Tomo. “More like inviting friends of ours who play instruments to come over and jam, and if we like what’s going on, we can always say, ‘hey, let’s roll some tape.”

Perhaps the most significant difference between these sessions and those for $1.99 Romances is that the eventual CD from these sessions will not be released on Geffen, the band having been finally released – liberated, it might say – from its contract with that label in June of ’95. The subject is a bitter one for the band. Tomo says it most conclusively: “Geffen Records has not done a single thing for God Street Wine.” In the absence of a label, the band is paying for the project themselves, having worked long and hard on the road to get the money together for the sessions.

1994’s tour, built on the success of prior roadwork, has seen God Street Wine gradually becoming one of the top touring bands in the Northeast. Its venues continually grow larger, now including those lucrative college “spring fling” gigs and a climactic, tour-ending show in late May at New York’s Capitol Theater. August marked the band’s greatest touring adventure when it joined Blues Traveler, the Black Crowes and many others on the bigger-than-ever H.O.R.D.E. tour.

GSW has expanded to the West and South as well. A fan on the summer Dead tour who had seen the band in Las Vegas described its performance there as “sick, amazing… they were phenomenal.” God Street Wine is definitely moving up into the big leagues. See them in a smaller venue while you can because that opportunity may soon disappear.

For Tomo, the secret of God Street Wine goes back to Princeton, New Jersey, where he and GSW’s vocalist/guitarist and main songwriter, Lo Faber, grew up, playing together in bands throughout high school. “It’s the water [in Princeton] or something,” Tomo says, pointing out that besides the two of them, Princeton has produced all four members of Blues Traveler, Mary Chapin-Carpenter, Chris Barron from the Spin Doctors and Trey Anastasio from Phish.

In 1988, Faber, who had hooked up with bassist Dan Pifer and transferred out of his economics major at NYU to study jazz at the Manhattan College of Music, phoned Tomo and told him the time had come to move to New York. Tomo, who was working at a car dealership in Princeton at the time, didn’t have to be asked twice.

After joining up with guitarist/vocalist Aaron Maxwell and keyboardist Jon Bevo in New York, the band rehearsed for three months, then began its career as so many bands do, on a Tuesday night in the humble environs of the legendary Lower East Side music bar, Nightingales. God Street Wine quickly became part of the same Lower East Side musical groundswell that was to produce Blues Traveler and the Spin Doctors.

Starting from those first club gigs, God Street Wine focused on the twin pillars of its success: music and road work. Through intense rehearsal and three or four nights a week of gigging, the band began to build an original sound and a repertoire of songs that now numbers over 200 originals. Faber’s earliest songs clearly showed his influences; “Imogene,” one of its maiden efforts, was accurately described by the Washington Post as sounding like a Steely Dan outtake. Over time, however, Faber developed a clear voice of his own.

The song “Princess Henrietta,” from $1.99 Romances, is representative of God Street Wine’s style, both in structure – with verse, chorus and bridge completely unique from each other; an extended, meticulously-arranged jam that sounds like it uses every chord change in the book; and the kernel of a catchy pop tune that keeps breaking out – and arrangement, especially in the interworkings of the guitarists, as Faber’s jazz-influenced guitar melds with Maxwell’s more burly, almost ‘70s rock guitar phrasings. The work between the guitarists is the trademark of GSW’s sound. The band also features extensive use of four-part harmonies.

And then there is Tomo, whose ability to move through a wide range of styles, from snare-pounding rock, to high-hat heavy jazz, to tom tom funkiness, matches Faber’s eclectic writing style and makes the drummer, along with Maxwell, perhaps the member most adept at his instrument.

In the early days, the bridge and jams threatened to choke the songs. The joke around the scene was that one day the band would put out a double live album with three songs on it. As the tunes have evolved, the band has consciously toned down the more noodling aspects of its arrangements without losing the ability to jam when the time is right. There was that night in Delaware last May when GSW played the whole show straight through, without a set break, without stopping at all, with each member being given responsibility for linking a couple of the songs together. Later that week, at the Capitol, the songs were self-contained and carefully sequenced. Experience enables this band to play within its own form.

But it was touring, extensive grassroots gigging, that built the franchise for God Street Wine. As Tomo puts it, “It became apparent to us that a record company wasn’t going to come up to us and say, ‘Do you guys want a deal?’ by us playing the Bitter End once every two weeks.” Besides, he says, “We found that playing live was what got us off.”

From the earliest days, the band attracted a group of fans known as “Winos,” who followed them to all the gigs. As the band developed, so did its fans base. Soon the band developed a mailing list, then a phone hotline and finally an Internet address where fans can get tour information, set lists and sometimes even answers to questions from band members who occasionally log on.

A major turning point for God Street Wine came in 1991, when the band held a meeting to decide, in effect, whether to settle for being a bar band or to strive for something else. It chose commitment. “We said, ‘we either do this 100 percent, or not at all,” Tomo says. “And that meant everybody moving to the house [in Ossining] and basically rehearsing and doing nothing but music.” So they all quit their day jobs, and the house became home to all five members of the band and its road crew, a place where rehearsals could take place at any hour of the day or night, where the band’s nascent four-part harmonies could be worked on, or where new songs or new arrangements could be worked out. Tomo credits the move to Ossining with really pushing the band on the road to success in terms of its musicianship and commitment to doing what it would take to succeed.

Then came what should have been the climactic moment of the band’s career: a contract with Geffen Records and the release of $1.99 Romances. According to Tomo, despite many words of encouragement from Geffen, the label’s lack of support for the record was apparent from the beginning. “It’s not like [Geffen] helped out a little and [the record] just bombed; they really did absolutely nothing,” he says.

The band began to realize what was, or wasn’t, happening soon after the album was named #4 most-added on to playlist on Triple-A radio, an alternative format that has served as a launch point to AOR radio and commercial success for acts like Sheryl Crow and Pearl Jam. “At that point, [it was] looking really good,” Tomo says. “It was time for the album to go to AOR, and Geffen just didn’t do it. Nothing. Like a wall, like a fucking wall.”

The experience with Geffen has made the band a little gun-shy about dealing with labels, which is why it is not rushing into another contract. GSW will record first, then take the product around to those labels who have offered them a deal and who are as puzzled as the band over Geffen’s lack of support. The band refuses to look at the experience with Geffen as any kind of omen, remaining convinced, as apparently do those labels wanting to sign them, that God Street Wine can become a successful recording act. “We’d like to be known as recording artists, as opposed to the road hog road warriors,” Tomo says. “Phish makes their living playing live, sold-out sheds. They don’t sell records. We want to sell records. We really do.”

The road warrior reputation coupled with the way God Street Wine has gone about building its grassroots following and the nature of its crowd ( “The same audience any band has today,” Tomo says, “your basic semi-affluent white kid” ) has elicited what seem to be obligatory comparisons to the Grateful Dead and Phish.

Sometimes the band gets tired of the comparisons. Indeed, there was the review of a GSW show by New York Times rock critic Jon Parales, who mentioned the Grateful Dead more often than the name of the band he was actually seeing, which convinced some people that he was paying more attention to the audience than to the music. “People need labels,” Tomo says, “until you get to the point where you get established enough, and then people start comparing other people to you.”

For God Street Wine, a band that has been following a relatively smooth, if not necessarily meteoric, path of ascension in the music business, the troubles with Geffen were a blow, but there wasn’t all that much time to think about it with the Ossining sessions to finish, the bigger rooms to play and the little matter of the H.O.R.D.E. tour followed by another round of touring this past fall. “It’s never taken a huge step backwards,” says Tomo, referring to the band’s career. “This ordeal with Geffen, at times it seems like going backwards, but the reality is it’s just another lesson.”