Glen Campbell: A Satisfied Mind (2011 Interview by Ira Kaplan)

Upon the death of Glen Campbell at the age of 81, we share this 2011 interview in which the singer, guitarist, TV host and actor sits down with Yo La Tengo frontman Ira Kaplan on the eve of releasing his final album of original music and final tour as he battled an increasingly debilitating case of Alzheimer’s disease.

When offered the opportunity to interview Glen Campbell, I didn’t have to be asked twice. But I did have a question that couldn’t wait, so I asked his publicist: What could be in it for the 75-year-old legend, after 60-plus years in the business, having gone public with his diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, to set up camp in a New York City hotel and talk the day away with some journalists?

The answer was touchingly simple: He’s got a new record and with that comes the job of promotion, an understanding so ingrained by now that the calculus of benefits versus better things to do is no longer a consideration.

(A diversion and not the last: When Yo La Tengo had the privilege of opening three shows for Johnny Cash in 1994, among the many awe-inspiring things that these three flies on the wall witnessed was Johnny – clearly not in the best of health – going into a suburban Philadelphia theater parking lot after his concert to sign autographs for as many people who wanted them.)

Glen Campbell – where to begin? The hits, perhaps, or maybe not. Lots of people have made hit records, but has anyone had a career like Glen Campbell’s? Here’s a guy whose behind-the-scenes work as a session player would be enough to make him a vital part of rock history; and then he eclipsed it with what followed. Who else can that be said of? Carole King and…can you think of someone? I can’t. (How appropriate that their careers overlapped when Campbell played guitar on some of The Monkees’ songs that King wrote.)

Campbell is everywhere – equally comfortable working with two of the most polarizing artists of the ‘60s, Tommy Smothers and John Wayne (the latter of which got him caricatured by Mad magazine). He’s on Lenny Kaye’s “first-psychedelic-era” Nuggets comp, of all places (side four, track four: “My World Fell Down” by Sagittarius, lead vocal by Glen Campbell).

After losing a bet – I could look this up, but I’m enjoying the haziness of the recollection – Johnny Carson paid up on-air by singing “Rhinestone Cowboy” astride a horse, one American icon acknowledging another.

My personal portal into Campbell’s world is “Guess I’m Dumb,” the impossibly beautiful 1965 Capitol single co-written and produced by Brian Wilson, perhaps as a thank-you when Campbell filled-in on tour for Brian, in the role later filled by Bruce Johnston.

(Another diversion: In one of life’s great coincidences, I met the co-author of “Guess I’m Dumb” just a few weeks prior to my interview with Campbell. While rehearsing for the Ponderosa Stomp’s “She’s Got the Power” girl groups show where I played in the house band, a gentleman sat down at the piano to play The Cookies’ masterpiece “I Never Dreamed” with us and was introduced as none other than the great Russ Titelman!)

I heard the song for the first time on a 1981 Australian Beach Boys Rarities LP. As the obscurities of Nuggets inexorably led to the deeper secrets of the garage-focused Pebbles series, the failure of “Guess I’m Dumb” in the marketplace reinforced that the music that was going to strike the loudest emotional chords for me was likely in hiding, and, 30 years later, it seems like there’s more digging to do than ever.

Memory is a slippery thing at best. Tell a story enough times and it acquires a truth of its own. (One last detour: As a youngster devouring rock magazines, I couldn’t believe it when I read artists profess not to listen to their own recordings. Personal experience has taught me not only that it’s true, but that I frequently don’t even recognize records I’ve made when I hear them played. Songs take on a life of their own in the intervening years to the point that they zig right where you would’ve sworn they zag.)

I’m not sure that what follows is an interview.

Talking to Glen Campbell today – as warm, generous and affable as he is – is something else entirely (at least it was for the hour I spent with him). He didn’t answer the questions I asked so much as seize on a word or phrase to jog him somewhere or other. It’s entirely possible that to some extent, he’s always been this way – he would hardly be the first interview subject to talk about what he wants to talk about, regardless of where the interviewer tries to steer the conversation.

But clearly his condition is affecting him. We at Relix elected to edit the transcript with a heavier-than-usual hand, in the interest of readability. Campbell and I were joined by his wife, Kim, who served as his pass protection, getting him back on track when his mind blanked, filling in facts when they went missing or were in error, and very politely bringing up his new Ghost on the Canvas record every so often, when it seemed like neither her husband nor this Wrecking Crew-obsessed interviewer were going to do so.

And when it was over, unbidden, but correctly taking the measure of his audience of one, he sang “Guess I’m Dumb” for me.

EARLY DAYS

Campbell, born in 1936, grew up on an Arkansas farm as one of 12 children. His parents were cotton sharecroppers and, in order to make ends meet, the children frequently helped them in the fields. The entire family, as Campbell notes below, was musical. Glen, in particular, showed musical promise to the degree that his father bought him a $5 Roebuck guitar from Sears, fashioning a capo – a simple device that would have a key role in Campbell’s career – out of a corn cob to make the strings easier for his four-year-old son to strike chords on. He credits his Uncle Boo with teaching him how to play. (As a teenager, Campbell eventually moved to New Mexico to play with another uncle, Dick, in his band The Sandia Mountain Boys.)

As a little boy, you listened to the radio, right?

Whatever I could get on the radio. It was a battery radio – if it went out, that was it. Daddy didn’t buy another one.

And did you strictly listen to country music?

It was everything from country to jazz to big band. I listened to anything that I could get on the radio because that might be the only chance I would get to listen to that song ever. [Laughs.]

It seems like your whole family was musical.

They were singers and all of them could play chords. Everyone was what we called a “hokum player.” (Ed note: A hokum player is someone who is not necessarily a good musician but is a good player.) Music was something I wanted to do full-time.

What instruments were in your house?

We had a guitar – that was mine – and a mandolin. That was it.

Your father also played the guitar a little bit. Would the family sing together?

Oh, yeah. We’d sing everything.

Kim Campbell: The brothers did a lot of Bob Wills’ stuff together. The Western swing – that’s what Shorty and Gerald wanted to try.

It sounds unimaginable that a family of that size would be living without electricity.

We sang and played anywhere. It was amazing.

Kim: His mama said she’d be pregnant – out there picking cotton – dragging another baby along on a cotton sack.

INFLUENCES

Part of what made Campbell such a fantastic session musician and solo artist was his wide range of influences. In place of any formal musical training was inspiration from musicians like gypsy jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt and country music luminary Hank Williams. While these types of early influences provided the bedrock for Campbell’s musical sensibilities, he continued to adapt and change through his various gigs as a sideman, song interpreter and tour partner with bands and singers ranging from The Beach Boys and The Champs ( “Tequlia” ) to Frank Sinatra and Neil Diamond.

You talk about listening to everything. Was rock and roll just another kind of music for you? Were you against it?

There are some good licks in rock and roll stuff. But it’s basically one- or two-dimensional, something like that. When I started playing, I listened to Django Reinhardt. I got a tape – it was him and [jazz violinist] Stéphane Grappelli. Django Reinhardt was the best guitar player that ever lived on this earth. He would play stuff that was just alien, man. [Laughs and imitates Django’s guitar playing with his voice.] I sat there and just laughed as I listened to his record. And they did all those songs from way back, like “Sheik of Araby.” He’d do the lick and then he’d play his own lick over it. I wish he had lived long enough to have recorded some more of those songs, because they would have been wall burners, you know what I mean? [Laughs and skats Django’s playing style some more.] It was maddening!

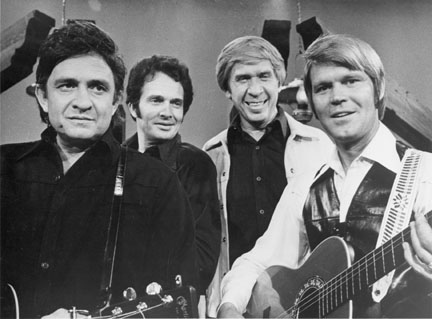

Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, Bucks Owens and Campbell on the set of his show, The Goodtime Hour on January 11, 1972

It seems very special to me that someone like you, who loves Django Reinhardt, was not anti-rock and roll – you could appreciate everything. A lot of people in your position would reject certain types of music.

Mmm, hmm. I listened to it strictly for the music and if they didn’t like it, I liked it. In other words, I wanted to listen to what I wanted to play and sing. I was given the freedom to do that with my Uncle Boo and the band. I was a very young kid and they said, “Just play what comes in your head – make up a song if you can.” That didn’t hold up for very long. [Laughs.] I said, [singing] “Oh, I love you darlin’” or some dumb thing. It was probably as abstract as that. When I went out to California, that was the whole ball game right there. I got to see some of the best players in the world then. Wow, it was something.

You toured as a member of Rick Nelson’s band. Do you think you learned anything from his singing style?

He had his own way of singin’ and the way he did it really came out good. [Singing] “Hello Mary Lou.” I thought he held onto things a little bit. I wouldn’t have [singing again], “Hello Mary Lou, Goodbye Heart.” He would drag things out a little bit more than me, but he was really a good singer. He doesn’t sing anything up and down – it’s just good, basic, straight ahead singing. And he had a good sounding voice too.

SONG SELECTION

Campbell actually didn’t write any of the songs that he’s best known for. Instead, he relied on his instincts for knowing a good melody when he heard one in conjunction with having a few key writers regularly feed him new material. Part of Campbell’s gift is his ability to hear how he could reconfigure a song as his own in real time. Despite some initial success with Buffy Saint-Marie’s “The Universal Soldier” and his own “Turn Around Look at Me,” it wasn’t until he took on John Hartford’s “Gentle on My Mind” that Campbell became a true star. And his work with the songwriter Jimmy Webb delivered his steadiest stream of hits: “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” “Witchita Lineman” and “Galveston,” among others.

Glen: It’s like the guy who asked me, “Who are you going to please with that?” I said, “myself.” I was going to please me. And I don’t mean that as a selfish thing. I’d ask the writer, “Do you mind if I change up a couple of things here and there?” And he’d say “no.”

Let’s take “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” as example. How did you first hear that song? Did you hear as a demo record or did you hear Johnny Rivers do it?

Pat Boone was the one who did “By the Time I Get to Phoenix.”

So, did you hear his version and think, “I could sing that song?”

I went by how good the song was. I never listened to how good the singer was. Had I, it would’ve caught my ear. And Pat Boone did catch my ear. Not singing it, but it’s the way you phrase something. He sang, “By the time I…[pausing]…get to Phoenix.” I don’t know what made him want to do that. You know [snapping his fingers and singing] “By the time I…get to Phoenix…She’ll be risin’.’” It didn’t rhyme, so I did it the way I wanted the song to be. If I wanted to hear it that way, I put it that way.

Did you improvise it in the studio or had you rehearsed it and knew that’s how you would sing it?

The guys that I knew that had records out, I would see how they phrased them. Like [Boone] doing, “By the time I…get to Phoenix.” I think you’ve gotta keep it in context. Later on, I found out that that’s what I was doing with the phrasing – totally unknown to me. I said, “Thank you, Lord. Wow. This is a better way to sing it.” [Laughs.]

Kim: He’ll change tempos, too. He’s known for that. Like “Galveston” was so slow when [Hawaiian singer/entertainer] Don Ho did it.

“Galveston!” He goes, [singing slowly] “Galvestoooonnn…Oh, Galvestoooonnn.” I said, “My God, when’s it gonna stop?” [Laughs.] I believe in me and it’s worked for me. I’ve been successful with it.

“Galveston” is a beautiful song. How fast did the band rehearse it?

I had mine down like I wanted it. And I told the guys what to do.

In your brain, do you know how you want it to be and then go into the studio?

You don’t know how many times I’ve looked up and said, “Thank you, Lord.” I don’t know where it came from. It would come out and be just, “wow!” Especially with “By the Time I Get To Phoenix.” I was cryin’ at myself before we were with Jimmy [Webb]. It was such a great song with great lyrics. Now, with a great lyric like that, I’d want everybody to hear it.

Those Jimmy Webb songs – you made them sound easy. And they weren’t easy.

They weren’t.

What was the process like with Jimmy Webb? Was he writing songs and you’d choose or was he writing songs specifically for you?

No, he was just writing in general and I’d choose the songs.

Kim: Except for “Wichita Lineman.” That was the only song – or the first song – that Jimmy ever wrote specifically for a person. [Longtime producer] Al DeLory and you were doing a record and you had had great success with “By the Time I Get to Phoenix.” They called him and said, “Jimmy, write us another one just like ‘Phoenix’ right away.” He was writing “Wichita Lineman” and Al called him and said, “Is it done yet? Is it done yet?” and he goes “No, it’s not done!” Al says, “Well, just bring it over here like it is!” They brought it to him and that’s how that guitar solo happened because Jim thought it was an unfinished song. But Glen put that great, famous guitar solo in it and that became the record. That was Jimmy’s first attempt to write specifically for one person, and he wrote it for you, and it’s the most played song of…

Most played song of the millennium. Most played in the world!

Kim: I think Jimmy won some kind of award at a songwriter’s thing for that.

I was an incredible – what I would call it?

Kim: A song doctor, right?

A song doctor. Like [singing], “She’ll probablyyy stop at lunch.” You don’t say “probably” ! You say “probly.” Because prob-ab-ly doesn’t sing very well.

I guess that’s why it’s your record. You’re not the songwriter and you’re not the producer, but it’s your record, because it’s got your stamp on it.

Kim: Which is another thing [producer] Julian [Raymond] has done with Meet Glen Campbell – he gave them all Glen Campbell flare and on the new album, you can hear hints of Gentle on My Mind, Wichita Lineman and the instrumentation. I know when [our daughter] Ashley was learning the new music, she would say “There’s a phrase underneath this in the strings that sounds like it just came out of ‘Wichita Lineman.’” (Ed note: Ashley is now a member of her father’s band.)

Those records – the first big hits – it’s like a type of music that didn’t exist. “Galveston” and “Wichita Lineman” are like country but they’re pop. It’s a mixture, very personal and unique.

I’m not a country singer, I’m not a rock singer, I’m not…

Kim: Pop.

Pop! Crock – that’s what I call it. Crock is a mixture of everything. I always played something that I wanted to hear. And Jimmy Webb – Jimmy was radical at that. He did some of the best songs and the best chord progressions in the business. Best I’ve ever heard. He was just awesome. He made the voice fit into many different changes without it changing very much.

But the songs that he wrote for The 5th Dimension are so different.

Kim: Jimmy sings that “Up, Up and Away” totally different than The 5th Dimension did. You should do that, honey! That would be good.

Oh yeah! [Singing] “Would you like to ride…”

THE WRECKING CREW

Campbell played on countless sessions with the fabled Wrecking Crew – Hal Blaine, Carol Kaye, Leon Russell, to name three of them. Here, he draws a distinction between himself and the great guitarist Tommy Tedesco. Where the latter could sight read any sheet music that someone put in front of him, Campbell played strictly by ear at first, never entirely learning how to read music. His trademark was the use of the capo, a device placed across any fret of the guitar neck to allow the player to play open folk-style chords in any key.

You started at the top in movies with John Wayne. But in music, you were 31 when “Gentle on My Mind” was a hit – all of those years doing amazing records and work that people didn’t know much about. You must have stopped thinking you were going to be a star by then.

I never even thought about it. I was enjoying myself so much playing with The Wrecking Crew I was playing with the best musicians in the world. Especially the real players, the writers and all that. And I was really, really thrilled with that. I got to where I could read a chart – no little notes or nothing like that – G, F, A, B, and that’s how they’d want it.

Because I could use the capo. And they were into that big ole’ open rangin’ sound – rangin’ sound, not ringing sound, I guess – and that’s what I’d do. I’d just use the capo. Put it here, put it in any position, ‘cause that’s what I do, you know. I’d play it by ear. And Tommy Tedesco would say, “what fret you got it on today?” [Laughs.] He was one of the best readers in the world. Once they started a song off and Tedesco, he would…[sings a complicated guitar pattern] and the guy would say “What are you doing up there?” And he had accidentally put his card on there.

Kim: He put his music upside down.

Upside down. And he was reading it backward. He had the intro or something, but he was reading it upside down and that just blew me away.

It was hard work, too. I saw The Wrecking Crew documentary and the grind of those sessions.

That was the whole growth of the really good stuff. It seemed like all of the music just crossed into one at that time – for me anyway – because that’s when I did all my best songs. I didn’t worry about – it seemed like it was just there. Tickled the hell out of me. [Laughs.]

You were there for The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations.” You were there when songs all of a sudden started taking more than three hours to record. It’s an amazing thing for people like me that you just walked in and said, “Here’s how it goes,” and two hours later, the song was done.

The union wanted to change. [Laughs.] Well, I think it destroyed the union and all that stuff for those eggheads. ‘Cause we’d go in there and it’d be, “Oh, is that how it goes?” and ding-ding, bang-bang [the song would be completed]. We’d get it done in an hour and a half and you’d still get paid for the three hours. [Laughs.]

Kim: That’s the way it worked with Julian Raymond on Meet Glen Campbell and Ghost on the Canvas. Julian would bring him songs by other people and then they’d listen through them and Glen would say, “I want to do it at this tempo” or “I don’t like this lyric, let’s ask them if we can change that one word to this.” Julian would record it like he wanted it and the band would go in and sing it, and it was done. Like he said, it was really fast.

Except Phil Spector, who you worked with – he wouldn’t let you do it in 20 minutes. He would make you play it again and again.

He would sometimes. [Laughs.] He was a strange guy, wasn’t he?

Brian Wilson took his time in the studio, too. When you listen to the Pet Sounds sessions, it’s just take after take after take.

[Pet Sounds and The Beach Boys] was some of the best stuff ever. And Brian was just a genius. You know, I don’t even know what the stuff is around today.