Fillmore Fellow Travelers: Carlos Santana Reunites His ‘Santana III’ Band

It took quite some time for the years to melt away.

The alchemy itself was nearly instantaneous, as decades dissolved within moments, expunged by a few musical notes. The moment of inception, however, required countless months of preparation.

“I’m so glad I chased this with Carlos,” explains time-travel catalyst Neal Schon. “I was on a mission, and I just thought how great it would be to go full-circle. I was met with a lot of resistance, but I kept running into him. It felt like an omen. If I was down at the mall in Corte Madera, [Calif.,] then he was there. If I went to a restaurant, then Carlos was there. He probably thought I was following him… and I was.”

Schon, who was still a teenage Bay Area guitar prodigy when he spurned an offer from Eric Clapton and joined the Santana band in late 1970— only to depart a couple years later to form Journey—laughs at his joke.

“Seriously, though, at some point, it felt like a sign from above that I should pursue this. Carlos finally said OK because I was driving him nuts. So we sat down and talked about what we could do together, and putting the original band together was part of that discussion. I knew there was going to be healing involved, but I really thought this would turn people’s heads around.”

Carlos Santana acknowledges that Schon’s pure intention and raw indefatigability finally held sway. “My heart surrendered to Neal because he was so gracious and vulnerable in the way he was approaching me. It’s a supreme compliment that Neal’s heart and his graciousness were so diligent. He was looking at me the same way I look at John McLaughlin, Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock. I needed to sit down with Neal and say, ‘That’s so complimentary’ because usually guitar players are like dueling banjos, and I never wanted to do that with him or Jerry Garcia or Eric Clapton or anybody.

“Some people want to compare or compete; I just want to complement and compliment. If Jerry Garcia goes up and down, then I’m going to go left and right. If Jerry Garcia goes left and right, then I’m going to go up and down. And Neal constantly put his ego aside in reaching out to me and saying, ‘I really want to play with you; I think we need to do something together.’”

While the impetus came from Schon, the musical direction flowed from Santana, who reflects, “When we finally decided, with clarity and integrity, to do a new album, I said, ‘Why don’t we call it Santana IV?’ Because I think, after the third album, it wasn’t Santana anymore. Caravanserai [the fourth Santana record] was an experiment. I think Santana III was the last collective, in unison—not looking over our shoulders at what Weather Report was doing or what Miles was doing. I thought, ‘Why don’t we accept that this is Santana IV, which is a continuation of Santana III.’”

Gregg Rolie, the group’s original keyboard player and vocalist, was touring with Ringo Starr in the Pacific Rim in early 2013 (at the same time Journey and Santana were making the rounds), when he received a few enthusiastic texts from Schon about the possibility of a reunion. “I called Carlos when I got home,” Rolie remembers, “and what he said was: ‘I want to get the guys together and call it Santana IV because the band stopped with Santana III.’ I thought that was brilliant because it should be Santana 40— he’s done so many recordings. But it expressed everything in those two words: Santana IV.”

Originally dubbed the Santana Blues Band, Carlos’ group was a true product of the collegial Bay Area music scene of the late 1960s. “I take it as a badge of honor,” the guitarist says, “when I tell people, ‘One minute I’m in Mission High School, and then, the next second, I’m playing on a truck at the Panhandle, and I just smoked a joint, and I’m playing ‘Jingo’ and ‘Chim Chim Cher-ee’ from Mary Poppins, and I open my eyes, and I’m sweating, and there’s Jerry Garcia and Michael Bloomfield, looking at me and laughing.’ Not laughing at me, laughing with approval.”

The classic Santana lineup that would regroup over 40 years later originally came together piecemeal. In 1965, percussionist Michael Carabello was a high school student at San Francisco Polytechnic. Mutual friends introduced him and Carlos, who was then attending the nearby Mission High. The two shared a similar sensibility, and Carabello joined the guitarist’s nascent group, which was just starting to emerge from a blues-based aesthetic through exposure to artists like Gábor Szabó, Chico Hamilton and Willie Bobo.

Similar to many like-minded area musicians, Carlos was a steady presence at the Fillmore Auditorium, taking in all that promoter Bill Graham had to offer. One night, in October of 1966, during a chaotic set by the Butterfield Blues Band in which Paul Butterfield sat out due to an intense acid trip and Michael Bloomfield moved to organ— subbing for an absent keyboard player—one of Carlos’ friends secured an invitation for him to sit in for “Good Morning, Little School Girl.” He soloed alongside Jerry Garcia, who had showed up to lend a hand.

Santana’s efforts earned him a return invitation from Bill Graham, which soon yielded a new bandmate. A week later, Carlos was washing dishes at the Tic Tock hamburger stand when Tom Fraser, a singer and rhythm guitarist from Palo Alto, who had seen him at the Fillmore, tracked him down and invited him to a jam session. Carlos hopped into Fraser’s car for a ride out to a Mountain View, Calif., farmhouse, where he plugged in opposite keyboard player Gregg Rolie.

Santana’s efforts earned him a return invitation from Bill Graham, which soon yielded a new bandmate. A week later, Carlos was washing dishes at the Tic Tock hamburger stand when Tom Fraser, a singer and rhythm guitarist from Palo Alto, who had seen him at the Fillmore, tracked him down and invited him to a jam session. Carlos hopped into Fraser’s car for a ride out to a Mountain View, Calif., farmhouse, where he plugged in opposite keyboard player Gregg Rolie.

Rolie, who was also a teenager at the time, was playing in a Paul Revere & The Raiders knockoff band called William Penn & His Pals. Rolie’s group, which donned tricorn hats and uniforms, had gained a local following by performing the music of The Animals, The Yardbirds and The Rolling Stones.

Rolie recalls, “When I met up with Carlos, I realized he was doing exactly what I wanted to do, which was make my own music. We played in this farmhouse. It was all open field at the time, but it’s right where Shoreline [Amphitheatre] is now. We were playing real loud and the police showed up, and Carlos was 20 yards in front of me headed for this tomato patch. I thought it was a great idea and I joined him in the tomato patch.

“From then on, I was driving or hitchhiking from Palo Alto to San Francisco and working on Santana while I was going to college. I was going to be an architect, or try to be one, and the turning point was when I had a little meeting with my dad, who said, ‘You can’t do both. Give it five years and, if anything happens, great, and if not, you can always go back to school.’ That was his advice and I took it. I didn’t become an architect.”

Drummer Michael Shrieve’s indoctrination into Santana has a similar ring. He explains, “Michael Bloomfield and Al Kooper were playing [at the Fillmore], and I called all of my friends and said, ‘Let’s see if we can sit in.’ Everybody thought I was crazy, but I wanted to say I’d tried because Bloomfield was the Eric Clapton of America. I went up to him and asked if I could sit in, and he said, ‘Let me ask the drummer. He’s a really nice guy.’ So it happened and that was a big deal for me. Santana’s bass player, David Brown [who passed away in 2000], was there, along with their manager, who said, ‘We’re thinking of getting another drummer, and you sounded good. Can I get your number?’ I gave it to them and I never heard from them.

“Then, one day, as I was walking into this studio in San Mateo where I was hustling time, their drummer was literally walking out the door— they just had a falling out. A couple of the guys remembered me from that night, asked me to jam and then they asked me to be in the band right then and there. They followed me home to my parents’ house, where I woke up my folks and said, ‘See you later.’”

As Rolie describes it, although they were all still in their teens and early twenties, “The seriousness we had toward the music was everything. Carlos played with his back to the crowd. We played to each other, like jazz guys. It wasn’t some act going to the tip of the stage—it was all about the music itself. The most important thing was: How did it sound and where are we going with it?”

They developed that sound at Bill Graham’s Fillmore Auditorium (and later the Fillmore West) not only through their own performances, but also by soaking in the eclectic music bills at those venues. The diverse lineups served as a template for the music that the group would come to perform. Santana acknowledges, “You become what you love, you become what you adore—Miles opening up for the Grateful Dead or the Grateful Dead and Sun Ra or the Grateful Dead and Babatunde Olatunji. Then, it was Jeff Beck with Rod Stewart, headlining over Sly Stone, when Sly Stone was dangerous—this was before Woodstock. The Doors opening for The Young Rascals. Jimi Hendrix opening for Gábor Szabó and Jefferson Airplane. It was incredible and I was at the ground zero for adventure. Bill Graham was like Barnum & Bailey, Ringling Brothers—he was the ringmaster.”

During the summer of 1969, that ringmaster traveled to Bethel, N.Y., lending his assistance to the foundering Woodstock Music & Art Fair, on the condition that Santana, whose first album still had not been released, could join the lineup. Under Graham’s aegis, the group was in the Catskills a few days before the event took place and their very presence—at a time when traffic choked to a halt—thrust them into the spotlight through a spontaneous Saturday afternoon set. Originally, they were told they would appear three slots after the Grateful Dead, but when Jerry Garcia explained to Carlos that the Dead’s set would extend past midnight, Garcia offered some mescaline to help bide the time—so that when Santana performed more than 12 hours earlier than expected, Carlos discovered that his guitar had transformed into an electric snake, which accounts in part for the animated facial expressions that brighten the Woodstock documentary. The group’s career-making performance was amplified by the imminent release of their debut record, followed by the Woodstock film six months later.

By the time Santana started recording their second studio album, which would be called Abraxas, they had become international superstars. Yet despite the trappings and potential distractions that come with fame, they remained musical free spirits, still eager to pursue new collaborative opportunities that promised creative exhilaration. Such a prospect led Rolie to invite local guitar prodigy Neal Schon into the studio during the Abraxas sessions. Just 15 years old, Schon was the son of a jazz musician who moved his family to the Bay Area from New Jersey when Neal was 6 years old. Schon studied woodwind instruments under his father’s tutelage but, eventually, migrated to the guitar. “I got frustrated because he didn’t have much patience to teach me, so I decided to play something that he didn’t play,” he explains.

Schon devoted himself to the instrument from the age of 9 and, as a young teenager, turned heads. He became friendly with brothers John and Jack Villanueva, Santana crew members who took an interest in him. “Jack picked me up every week, took me into the city and introduced me to all of the club owners. He brought me to the Keystone Korner, where Elvin Bishop had this thing every week, where guitarists of all ages would have a shootout onstage for the title. I ended up keeping the title, so Elvin was kind to me. One night, he said, ‘We’re going to go down to the Fillmore. B.B. King is playing there, and I’m going to introduce you to him, and we’re probably going to be able to go onstage and jam with him.’ That was the first big show I ever played. I had studied all B.B.’s music, and we had a cool exchange onstage. I knew his picking style, vibrato technique and choice of notes, so he’d hit a note, and I’d look over and answer him. I had a lot of chops—I could be fast—but I decided to slow down, be tasty and show him respect. He loved that and we became friends. I played with him many times after that. The same thing happened with Albert King.”

Gregg Rolie became a booster and advocate. “He was brilliant at 15. It was amazing. He could play more of that Clapton stuff than anybody I’d seen, and he had that air about him. So I brought him around during Abraxas, thinking I would love to have his guy in the band, but it wasn’t my place to go, ‘We should have another guitar player.’ Although I thought it would be a great idea because they played differently. It could open up yet another color in this electric music we call Santana.”

A moment of truth arrived when Eric Clapton came to town with Derek & the Dominos. Bill Graham facilitated an informal gathering at Wally Heider Studios that swiftly evolved into a jam session. Carlos sat out after ingesting some psychedelics, but Schon dazzled Clapton, earning him an invitation to make a guest appearance the next night at the Berkeley Community Theatre. It went so well that Clapton asked Schon to join the Dominos, which, in turn, prompted a similar offer from Santana.

Shrieve laughs. “So here was Neal in the schoolyard the next day asking himself, ‘Hmmmm, should I go with Eric Clapton or should I go with Santana?’”

While flattered, Schon opted to play for the home team, which he held in the highest regard. Schon also had an inkling that drugs were taking their toll on Clapton and his group. He had arrived at the Berkeley Community Theatre to find everyone asleep. “I thought, ‘What’s going on, man?’ Even being that young, I sensed that there were some issues.”

Although his bandmates were somewhat surprised at Carlos’ willingness to welcome Schon into the fold, the band’s namesake explains, “Everywhere I looked, people were having two guitar players: Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir, Duane Allman and Eric Clapton, even Peter Green went out and got another guitar player. So I was like, ‘OK, there’s something about two voices creating one symmetry.’ I remember Miles Davis asked me, ‘Why did do you do that?’ I told him, ‘Because that’s what my heart told me to do.’ He said, ‘I think it’s a big mistake.’ Consequently, he had two guitar players: Pete Cosey and Reggie Lucas. At one point, he’d also had Sonny Sharrock and John McLaughlin.”

With Schon in place, the band started working on their third record, which would become the group’s second consecutive No. 1 album (and the group’s final chart-topper until Supernatural, 18 years later). Opening with the vibrant instrumental “Batuka,” featuring the guitarists’ twin leads, the record also includes the ebullient “Everybody’s Everything,” which became a pop hit, and the burning, FM-radio favorite “No One to Depend On,” both of which emphasized Schon’s new role with the group. Other tracks, including “Toussaint L’Ouverture” and “Guajira,” remain Santana setlist staples to this day. The band traveled back and forth across North America and touched down on five continents, earning lavish accolades for their dynamic live shows.

However, the road lifestyle began to take a toll on the group and, during the fall of 1971, Carlos said goodbye to his longest tenured bandmate, Michael Carabello. The guitarist had grown frustrated with an increased cocaine presence and staged a sit-down strike, leading the group to begin a tour without him. Schon helped persuade Carlos to return, but this also necessitated a personnel purge, which included Carabello.

By the time that Santana entered the studio for their next record, in the spring of 1972, a deeper schism had developed. Carlos writes in his memoir, The Universal Tone: “We had gone from rooting for each other to tolerating each other to being two bands in one, in conflict musically and philosophically.”

Carlos’ vision aligned with Michael Shrieve’s, who explains, “Bitches Brew was happening with Miles, and Return to Forever with Chick Corea, Lenny White and Stanley Clarke, and also Weather Report. It seemed like that was where the shit was happening, rather than just more rockand-roll music. He and I were moving in a different direction, spiritually, from the rest of the band, and we went guru shopping as well.”

Rolie attests, “I didn’t want to play all ethereal. I thought the exploration became more than the music we were doing. I thought it was great to educate our audience, but I didn’t want to lose them.”

As it turned out, the Santana audience would lose both Rolie and Schon by the time of October’s Caravanserai release and tour. After breaking from Santana, Rolie initially put the music world behind him, opening a restaurant with his father in Seattle. While he entered this partnership with great optimism, the venture began to take a toll on him. (“It’s like going from the pan to the fire. You think the music business is tough, try restaurants—you need 4,000% capacity to make it happen because no one’s going to eat in the same place every day.”) So, when he received a call from Neal Schon about the possibility of joining a new project to be managed by former Santana roadie Herbie Herbert, Rolie decided he was ready to reenter the music world.

“Originally, it was going to be called the Golden Gate Rhythm Section,” Rolie says, “and we were going to be a backing band for solo acts that came into town, like the Eagles did a few years later with Linda Ronstadt. But, that idea didn’t last long. Within two weeks, we started writing and everything came together. We needed a new name and that’s how we became Journey.”

Santana IV concludes with a soaring instrumental track titled “Forgiveness.” Schon and Santana’s guitars are in full communion on the first-take recording. The song is a fitting cathartic coda to the new record and the long process that birthed it.

In 1972, when he heard the name of the group’s fourth album, Bill Graham quipped, “Caravanserai? More like career suicide.” While Santana would later joke that he had gone through multiple “career suicides” over the decades that followed, this first one came with the dissolution of his original tight-knit company of Fillmore fellow travelers.

In The Universal Tone, Carlos discloses that during the recording of Caravanserai, “I found myself crying a lot— asking myself what was wrong. My body was shedding tears at the dismantling of my relationships with everyone, mourning the fact that we didn’t have each other’s backs like we used to. To this day, I listen to ‘Song of the Wind’ and break down inside hearing Gregg’s playing on that one— no solo, just a simple, supportive organ part that is not flashy or anything, but supremely important to the song.”

Given the raw emotions associated with that formative era, it is no wonder that Carlos initially remained standoffish to Schon’s entreaties. Beyond the four decades of roiling sentiment, Carlos was also juggling any number of ongoing endeavors as an artist, father, philanthropist and, as of December 2010, a newlywed, having proposed to drummer Cindy Blackman onstage that summer.

Schon remained upbeat and persistent, doggedly determined to work again with the man he still identifies as a mentor. “It was a five- or sixyear process. But, after talking to him many, many times, one day, he invited me to his house in the Bay Area. I always knew the original band would be a cool thing to do, but I didn’t want to come with that so fast, so I tried to ease into it. When we disbanded, it was not on a good note for everyone. There also was some healing involved with me and him. Growing up, I was a cocky little shit, and you say stupid things and you do stupid things, and then, you grow up and go, ‘Oh, that was really dumb and I’d like to amend all this.’”

Schon’s initial pitch was for a music festival he wanted to call Guitar Zoo. “I told Carlos we could get all our favorite guitar players from different genres. He thought about it and said, ‘Great, I can call Eric Clapton and you can call Jimmy Page, and we can get Jeff Beck and John McLaughlin…’ But as we were talking about it, I realized we had one major problem,” he says with a chuckle. “We weren’t going to have enough money to pay everybody.”

The idea then morphed into a studio album featuring many of these same guitar gods, before Schon returned to the concept that had originally galvanized him.

“As we continued talking, I said, ‘How about if we just did the original band?’ At first, he looked at me like, ‘What?’ But then he said, ‘Let’s do it.’ I had been talking to Gregg, Michael Shrieve and Michael Carabello to tell them I was working on it and they had said, ‘Dude, you are dreaming—that is never going to happen.’ It was kind of like, ‘Hell will freeze over’ with the Eagles and I had said, ‘Well, I’m getting a good gut instinct here.’ [The four musicians had kept in touch over the years and even recorded an album together as Abraxas Pool in 1997 along with former Santana members Alphonso Johnson and José “Chepito” Areas, the latter of whom also appeared on percussion during the early years of the group, but proved to be “difficult” when it came time to discuss reunion plans.] Then, all of a sudden, we got everybody on the phone and it was happening. We just had to wait until our schedules opened up and we were all free from our different tours.”

“We were in a holding position for quite a while,” Michael Carabello remarked at a press conference shortly before the April 15 release of IV. “There was talk of it for some time. I like to think of it as if we were part of a positive sleeper cell, that when they called and said: ‘This is your mission should you choose to accept it,’ we were ready.”

For Carlos, it became a unique opportunity to “get back together, jump on our horses and ride—not into the sunset, but into a new sunrise.”

They first saddled up again in 2013 at Carlos Santana’s rehearsal space in Las Vegas. Although the recording sessions would eventually include current Santana bassist Benny Rietveld and percussionist Karl Perazzo, initially, the five musicians went at it alone to gauge the vitality and viability of it all.

Gregg Rolie marvels, “We played for about six hours. It was incredible. The years disappeared. I could have done this last year or 40 years ago. It’s like old friends you haven’t seen for a long time and, then, you see them and it feels like you had just seen them yesterday. Playing with these guys, you kind of know where someone is going and if you don’t, you better be quick.”

The project immediately took on its own momentum, as the musicians began sifting through their grooves to identify seeds that could be nurtured and blossom into songs.

“I walked outside to get some fresh air after we’d jammed for 40 minutes,” Carlos recalls, “and when I came back, I said to Gregg Rolie, ‘You did this thing in the middle of this jam, and I’m going to grab that thing and that’s going to be the intro. And Neal, you did this and that’s going to be the verse and we’re going to do this…’ I’m very grateful and honored to say that they trusted me to be the interior decorator because, when you look at the music, it’s like a puzzle and I learned to do the borders first.”

The group crafted the instrumental “Fillmore East” in one take after Carlos suggested, “Why don’t we imagine what it’s like to scrape the wall of the Fillmore East and hear The Doors and Ravi Shankar and Miles Davis and the Grateful Dead and Sly Stone and Santana?”

Some of the material came in more fully formed, such as Greg Rolie’s “Anywhere You Want to Go”—the album’s first single—which features the band’s signature rhythms, punctuated by a resonant organ solo and strident guitar declarations. When asked if this song was written for its own sake or with this specific band in mind, Rolie responds, “When I sit down to write things, it’s always with this in mind.”

Santana IV fulfills its time eliding mission statement, and truly feels like a spiritual, sonic follow-up to Santana III. A similar rhythmic foundation undergirds Santana’s vigorous, melodic lines and Schon’s burnished, galvanic riffs. Rolie’s bright-hued organ bed and robust vocals are imprinted on both records. Just as III is enhanced by the presence of like-minded guest players, including the Tower of Power horns, IV features a guest turn by The Isley Brothers’ lead vocalist Ronald Isley. “Aretha is our queen and Ronnie is our king,” Carlos offers.

The public promptly embraced the latest embodiment of the Santana sound from the very musicians who pioneered that sound. The album debuted at No. 5 on the Billboard album charts and remained a Top-15 seller at Amazon weeks after its release.

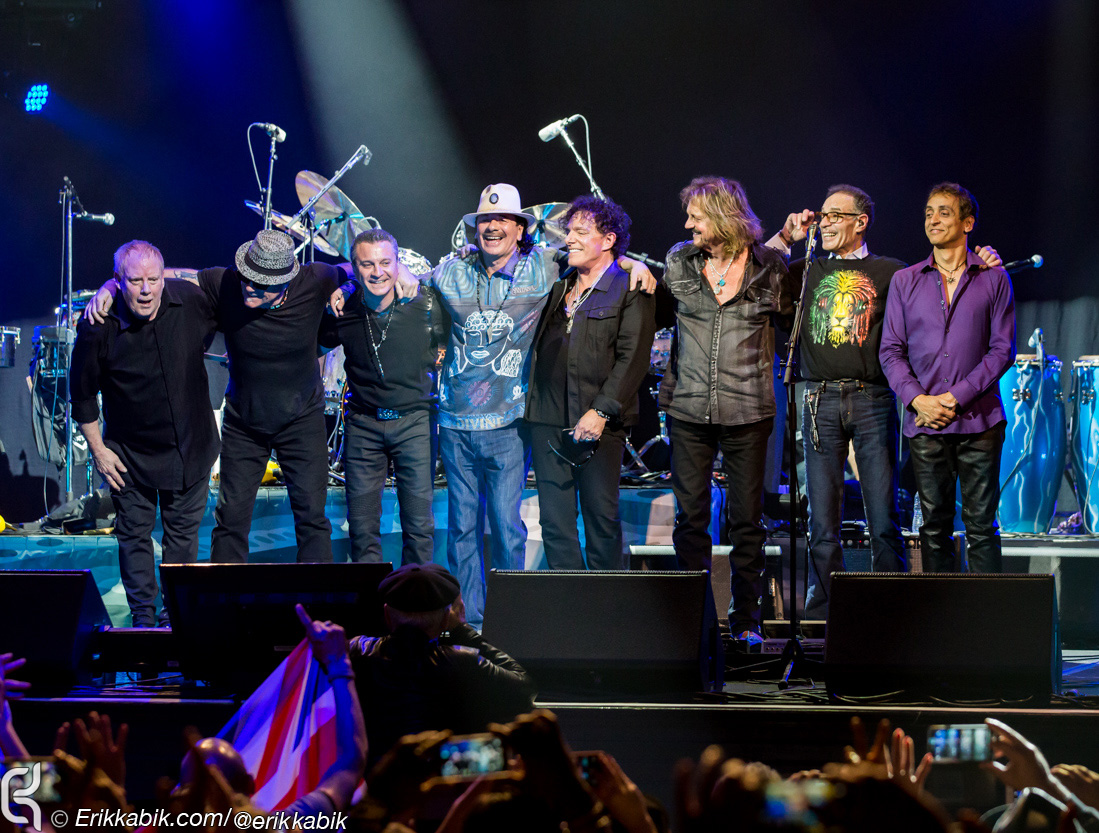

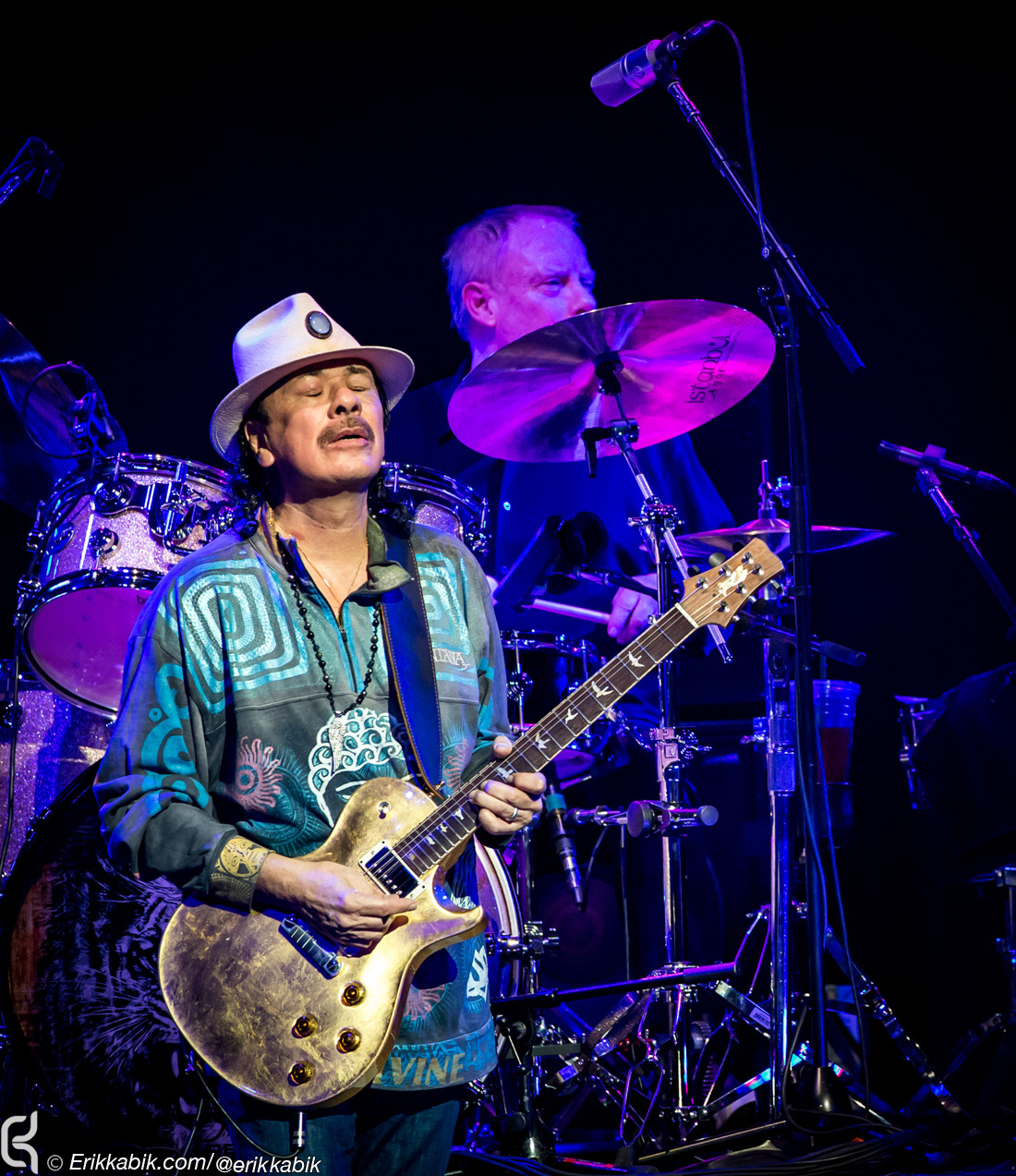

Still, while Santana has had historical success in the studio, the ultimate sandbox and proving ground for the group is the live setting. The band was put to the test for the first time on March 21, 2016, when they assembled for a special show filmed at the House of Blues in Las Vegas.

Michael Shrieve reveals, “What I did at 20 didn’t make it easier on my 66-year-old self, so I went into training: physical therapy three times a week, the gym, juicing, smoothies, practicing for hours, playing through a set with a heater on like hot yoga so I could put myself in that situation of being on the stage with lights, the whole thing. There’s a lot expected of this band. People don’t care about your age; they just want you to go out there and kick some ass. And we only had one night of rehearsal after not playing a gig in 30, 40 years, so you damn well better be ready. But it was really great; it was triumphant.”

Michael Shrieve reveals, “What I did at 20 didn’t make it easier on my 66-year-old self, so I went into training: physical therapy three times a week, the gym, juicing, smoothies, practicing for hours, playing through a set with a heater on like hot yoga so I could put myself in that situation of being on the stage with lights, the whole thing. There’s a lot expected of this band. People don’t care about your age; they just want you to go out there and kick some ass. And we only had one night of rehearsal after not playing a gig in 30, 40 years, so you damn well better be ready. But it was really great; it was triumphant.”

“The energy that comes off the stage goes to the people and, if they’re energized, they give it back to you and then it comes back to them, and it’s just a round robin of energy,” Rolie adds. “That’s what happens with this group because we play to each other and enjoy it. There are no phony smiles up there; it’s as serious as it always was, and it’s always been serious fun.”

The group’s first East Coast show took place at Madison Square Garden on April 13, the opener of a three-date co-bill run with Journey. (Schon is the lone remaining founding member; Rolie left the group in 1980.) In a fitting gesture that simultaneously reinforced the circular nature of the project while also acknowledging the passage of time, Bill Graham’s sons David and Alex introduced the group. Then, footage of “Soul Sacrifice” from the Woodstock film segued into a live take on the song, with Carlos, Rolie, Shrieve and Carabello transporting the sound into the present. After a run through “Jingo” and “Evil Ways,” the band paused for Carlos to greet the audience and make a special introduction—“I want to bring onstage an incredible musician. He’s responsible for this…. His name is Neal Schon…”

Clad in black sunglasses and a matching jacket, an exuberant Schon walked out and shared a high five with Rolie before the group charged into the opening numbers on III, “Batuka” and “No One to Depend On.” Then, to manifest the transition to IV, the group segued from 1971’s “Taboo” into 2016’s “Shake It,” which yielded a sequence of new material, reinforcing the unity of intention and pulling the audience into what Carlos describes as “a circle of collective commonality.”

The band members have uniformly articulated a desire to continue. Schon notes that the studio sessions produced “about 50 ideas that we didn’t even use on this record. When we get together, it’s like it just falls out from the sky. It’s a magical combination of people.”

Carlos is initially guarded as he considers the future of this incarnation of Santana: “I want to create Santana V and make a trilogy, but I’m waiting to see how it all unfolds.” He expresses interest in bringing the group to festivals like Lockn’, where he performed with Phil Lesh last summer. (“That was a lot of fun. I felt like I was a dolphin going in and out of the water.”) Beyond that, the longtime band leader emphasizes the complexities of bringing a group on tour, with proper lighting, sound and transportation while ensuring that everybody is compensated “with equality, fairness and justice, so that it feels like we’re all contributing not only to the music, but with the investment.”

Some of this sentiment may be tied into the dissolution of the original group in 1972 and might also reflect on Schon’s initial need to chase down his mentor. Still, after a pause, Carlos muses on the band’s origins and affirms where his heart lies: “My teachers are still with me. They changed their zip code, but they’re still with me. Bill Graham is with me; Jerry is with me. I would never want to sound cute or clever or plastic. That’s against anything that I’m about. I am what I learned from Bill and Jerry Garcia. They taught me to expand, transcend and have fun. Don’t become predictable, pathetic and boring. That’s what I learned back at the Fillmore and that’s why Santana IV is easy for me to do. I’m with people whose sound is their life and whose life is their sound. I am not going to fail Jerry Garcia or Michael Bloomfield or Bill Graham. I am not going to fail with my thirst for adventure.”