Documenting “New York’s Rock Kingmaker”: Director Jake Sumner Presents Ron Delsener

“It was a balancing act between being a personal story of an octogenarian who can’t stop hustling and also a history of live music,” director Jake Sumner says of his documentary Ron Delsener Presents, which opens nationally on Friday. “I think ultimately Ron is a great vehicle to tell a story about the larger picture of live music history because he is who he is. You couldn’t do that with anyone but he’s such a character. The film is also intended to tell a bigger story because Ron was at so many of these seminal moments in live music history.”

Although this is Sumner’s first feature-length documentary, he has been working in the medium for well over a decade. Ron Delsener Presents benefits from his visual acuity as well as his deft touch with narrative. The film draws on extensive archival materials sourced at Delsener’s house, as well as conversations with numerous celebrated artists, including: Billy Joel, Patti Smith, Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, Jon Bon Jovi, Stevie Van Zandt and Bette Midler.

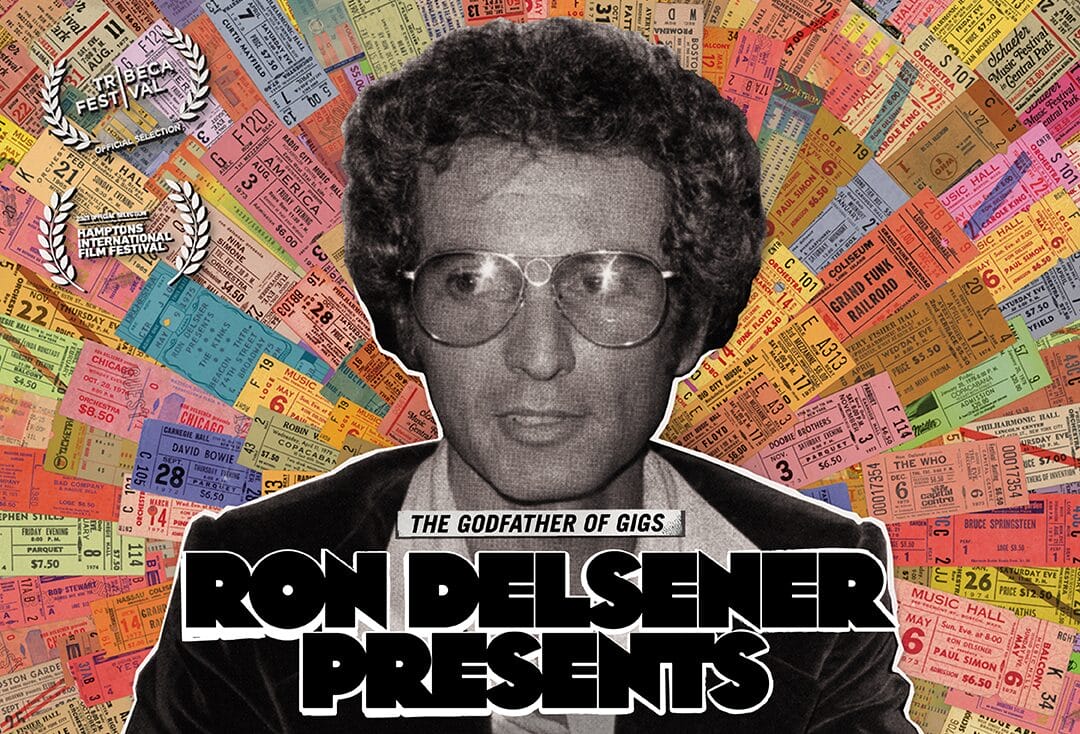

Sumner’s Director’s Note includes the following thumbnail sketch of Delsener: “As someone who was there in the early days and involved with booking The Beatles, Bob Dylan and Harry Belafonte at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium, to organizing a network of regional promoters for what would eventually go on to become the multinational entertainment giant Live Nation, Ron’s career spans the story of how live music became what it is today. From infamously auctioning off The Beatles dirty bed sheets and cigarette butts left in their hotel room in 1964, to maneuvering a little known act called David Bowie into Carnegie Hall in 1972, to turning an old vaudeville theater on 14th street into New York’s iconic Palladium, hosting acts like Patti Smith, Frank Zappa and The Clash; Ron recounts how the Wild West of live music became a cultural phenomenon – and for better or worse – the multibillion dollar enterprise it is today. Perhaps, the biggest feather in Ron’s cap is bringing Simon and Garfunkel together for their reunion in Central Park, an event that simply would not have been possible without Ron’s mastery of the telephone. For all of Ron’s bravado and without having any musical ability whatsoever, Ron is someone that has brought joy through music to generations of people.”

The documentary offers a dynamic portrait of the promoter and the industry in which he thrived for six decades. It presents this tale with energy, enthusiasm, and empathy.

Audiences can experience the film in theaters across the country over the coming weeks with special guests on hand in certain instances. Those who attend the 7:15 screening at Manhattan’s Quad Cinema this Friday, May 30, will also be treated to a Q&A with Sumner, Delsener and Peter Shapiro (a longtime friend of Ron, who offers insight and humor throughout the film). On Saturday, May 31, Sumner and Delsener will return at the same time with executive producer Margaret Loeb. The full list of cities and dates appears at the official website.

Although you’ve been making films for many years now, this is your first feature-length documentary. Can you talk about the process of finding your voice as a filmmaker and how that informed your approach to Ron Delsener Presents?

I grew up loving movies and I imagined I would be making narrative movies. Then somehow I fell into documentary. I made a documentary about a Nigerian musician named William Onyeabor [Fantastic Man: Who is William Onyeabor?] I made it with Luaka Bop, David Byrne’s record label and I ended up going to Nigeria in order to work on it.

It was a larger than life story and it helped remind me that the world is full of amazing stories that don’t need to be written. There’s no reason why a documentary can’t be very cinematic and these stories are already there to be told.

I also think I’m interested in figures who may not have gotten the spotlight or are behind the scenes in a way, yet their influence is immense. I think there’s a connection between several of the subjects I’ve made films about. I’m also interested in larger than life characters and Ron Delsener is definitely one of them.

You continue to direct short films as well. Your documentary Seaweed Stories, which Forest Whitaker narrated, played on the festival circuit last year. Do you have a preference between shorts and feature length?

Shorts are good because you can do them at a faster clip and learn a lot, but I also think shorts are harder to place. There aren’t many good homes for shorts.

So I definitely prefer features but it’s also a matter of the time that’s required. Ron Delsener Presents took years to make. There are a lot of factors that go into making a feature including gathering all the interviews and the material that can sustain a 100 minute film. It takes time because there are also rights clearances and the approvals process.

Since you mentioned it, clearing music and video for general release can be complicated. When a film is playing festivals securing those rights is one thing but then clearing them for general release is much more complex. How challenging was that for you since Ron Delsener Presents features so many notable performers and songs?

It’s a whole art unto itself. We were lucky to work with someone I would say is the best music supervisor in the game in Randall Poster. I knew his sister Meryl who gave me his email, but I had never met Randall. So I emailed him and just said, “I’m making a documentary about Ron Delsener. Do you any interest?” He does Wes Anderson movies and The Hangover and works with these giant Hollywood films and filmmakers, so I didn’t have any expectation. Also, we couldn’t really pay him his rate, but he responded immediately and said in capital Letters “RON DELSENER PRESENTS! I was at all those shows. Of course, I’d love to be involved.” That was a huge win for me and for the project and it made clearing the music a lot easier.

Thinking back to the beginning of production, can you talk about the process of finding the various themes and throughlines?

At first, it was just kind of following Ron around with a camera. Then it started to evolve when I realized the extent of his archive and that he is a window into live music history in this really profound way. I don’t think there are other people who are still alive, who have the history that Ron does.

I’d known him for a long time in a way but not that well. Whenever I’d see him at events or shows, he always had these stories that were captivating. He’d just drop an incredible Jimi Hendrix story on you and have everyone kind of watching. What’s funny is that a lot of his stories are not very glamorous. They’re not what you might expect. Like they’ll end with him eating pizza with Elton John in the back of a car. That’s what I like about his storytelling—it’s not the super glamorous things you might anticipate. It’s walking through downtown Manhattan with Frank Zappa’s bodyguard to get a hot plate for Frank because he’s tired of the cold food that they would serve him in the back of the Palladium during his residency. I thought that stuff was just so compelling and interesting.

I think eventually in making the film and just hearing these stories, I felt that in totality they tell a story of how an industry went from essentially taking gambles on these sort of one-offs—moonshots essentially—to becoming a giant industry. I think Ron’s story can track that.

Then COVID gave us the time to dig into the archive that he’d accumulated in his basement. I spent basically all of COVID living in Ron’s basement, just going through his shit. [Laughs.] It was good because it gave me a project during a time where there wasn’t much else to do. But once I saw what was down there as far as material, I knew there was a lot to work with for the film.

Ron has all of his old contracts along with a lot of other ephemera down there. Can you talk about the process of sorting through all that?

The cabinets are one thing, but then everything else in the basement is kind of one big pile of junk. You have to dig to find a lot of this stuff in his basement because he’s kept everything. So it’s a mixture. He collected matchbook covers and he buys little ornaments in gift shops from any place he ever goes. He has merch from every concert ever and it’s not always good merch. [Laughs.] So it took a lot of time to find the gems in there, but that’s kind of what I love about his basement. It’s a museum in a way, but it’s very interactive and you have to get involved and find this stuff. Part of what was I think nice to Ron about the project, was we actually archived a lot of this stuff and gave him digital records of it all.

Going back to the very beginning of his career, Ron has been very hands-on, even to the point of assembling the chairs for some of his early shows. To what extent did he offer you suggestions?

Surprisingly, Ron wasn’t very controlling when it came to the making of the film. He cared more about the premiere and who was going to be in what seats and would he have enough seats for his guests and what would the food be like. He just snapped into being a promoter.

But in terms of us telling the story, Ron was relatively hands off, all things considered. He didn’t really have any sort of stipulations and he was very open with us doing it.

There would be days, of course, when he was mercurial. He threw me out of his house a few times. But that comes with the territory and I think that’s to be expected. I think with great characters, you have to know what you’re getting into as far as what might come your way and what you might have to do in order to get what you need from them to tell a story. I think the most interesting characters are probably the people that are a little tricky and difficult.

He is not an easy person to make a film about. You don’t really know what Ron you’re going to get on a given day. So that was a real challenge in itself but I stuck around long enough and sort of went with it. There would be times where it wasn’t happening and then it would be back on and happening again. So I sort of rolled with the punches and then it just sort of evolved into something.

How challenging was it to pull together all the people you interview in the film?

That was kind of the easy part. To be honest, some of the artists featured in the film reached out to us when they heard there was a project because they wanted to be involved.

Most of the artists in the film are from the New York City area or they came up here. That was intentional. I wanted to work with artists who were not only familiar with Ron from their own careers, but maybe from their childhood too, since he really started in ‘64. So that was an important aspect to it.

A lot of those artists, Ron gave their break in New York. They were playing clubs and what have you, but the next step was playing in theaters and then hopefully arenas. Ron was the guy who could help you get there. There were a lot of artists like Billy Joel, KISS, Patti Smith and the list goes on, who were happy and eager to share stories about him.

Ron maintained personal relationships with artists in a way that a lot of other promoters don’t, particularly in the current era.

He’s connected to so many of the acts from the of golden era in the 60s and 70s. But I think that Ron at heart is just someone who keeps tabs on people, who will turn up and be there. If you tell Ron, “Hey, there’s this thing, can you be there?” Ron will usually be there.

I think that matters. There are ebbs and flows in people’s careers, but someone like Ron is consistent. I don’t think the ebbs and flows really matter to Ron. I think he’s more drawn to the action and being around whatever it is. He’s maintained these relationships over decades.

You film is titled Ron Delsener Presents, which references the way his shows were billed for many years until he sold his business to SFX. In the current era of corporate promoters it’s rare to see individual names on a concert poster or ticket. What do you think has been gained or lost as a result of that change?

I come from the school of “we are where we are and it is what it is.” There’s no putting the genie back in the bottle. I think every major industry has been rolled up and corporatized. This wasn’t really an indictment on that. It was more of a way of looking at how it happened in this industry and how did it go from this kind of wild west cottage industry that was built by real gamblers like Ron and Bill Graham and a handful of others, but then turned into this multi-billion dollar global empire. Yes, you can credit the acts drawing the fans but there are people behind all of that who took a chance on these acts and put them in these venues.

My general feeling is that the record business always gets so much shine in terms of music history. So while you hear about that stuff, you hear less about concerts like Simon & Garfunkel in Central Park and how that happened. People know the name Bill Graham, but even with him, generally speaking, I don’t think people really understand the business of live music.

You’ve described Ron’s “mastery of the telephone.” In the film you demonstrate an approach that contrasts with Bill Graham yelling into the phone during the Last Days of the Fillmore documentary. However, from my own understanding and observation, Ron’s calls can also be rather concise, particularly compared to his effusive in-person storytelling. How would you characterize his technique?

Although he often keeps it short on the phone, I do believe he’s a bit of a master. I think the Simon & Garfunkel show wouldn’t have happened without Ron being able to reach out to Paul but kind of knowing that Paul was going to think about Artie and how that was going to work, and then reaching out to Lorne [Michaels] and how that shook out. I credit Ron with how it went from a Paul Simon show to a Simon & Garfunkel show.

So I would say that Ron has this skill on the phone, but I agree that he likes to keep it short. He doesn’t like small talk. Often the phone is for business, for “What do you want? Let’s figure that out.” No niceties, no bullshit.

In terms of people you interviewed for the film, beyond the many folks who reached out to you, was there someone you chased?

We were really hoping to get Art Garfunkel involved. It took a little while, but we did. He’s a wonderful addition to the film because he rarely gives interviews at this point, but was happy to in this case. It just took a little longer than most.

Beyond the story of Ron Delsener as a concert promoter there are a number of quieter, intimate moments that resonate. For instance, there’s that line when Ron is described as someone who’s surrounded by people yet is also something of a loner.

The films I enjoy most are the ones that might be about a certain thing, but there are underpinnings that tell a bigger human story. So you don’t really have to know about music of a certain time and era to be able to get something out of it.

Something that sticks out to me in the film is when Ron says that he doesn’t have any friends left to talk to in a real way because so many of his friends have passed away. That to me is a very real moment and something that resonates. He’s the ultimate sort of people person and the king of the five-minute conversation, who’s mixed it up with a lot of amazing people.

There’s also a moment in the film where he’s looking over these contracts from past shows that are in a filing cabinet. You realize for so many of those great shows, they didn’t even have a photographer there. They were moments that just existed in time and now the only evidence that they happened are in memories or in the contracts that are in Ron’s attic.

So I think they’ve taken on this degree of importance in his mind as these things that he made happen. I think all of his mementos and tchotchkes and everything that he’s kept are a bit of a reflection of that. I wanted that to be in the film. I felt like it was something that’s relatable. Life moves and savoring the moment is something we all strive to do and it’s something that we all sort of deal with. That was definitely on my mind in making this.

I was an early screening outside of New York with people who didn’t necessarily know Ron, yet they really connected with the more personal yet also universal aspects of the story.

Well, without sounding too lofty about it, I wanted the film to feel like a representation of Ron. I wanted it to feel like a kind of collage of moments in time, using different elements like animation or footage and not having it strictly be a biography.

I feel like these things have to fit the subject but I wanted it to be a ride.

When you finally screened the film for Ron how he did respond?

I think he was nervous before watching it and we were nervous to share it with him, but I think he enjoyed it. I think he probably didn’t think it would be very good because Ron kind of comes from this place where he thinks nothing’s going to work out. I think maybe as a promoter you have to be like that—you need to think that it’s always going to rain, and what if this happens or that happens? So when he saw it, I think he was surprised that he liked it and that we had done a lot of work to source great interviews and great archival and put it together in a real way.

I imagine it must be a weird experience to watch a 100 minute film about a career of yours that’s gone nearly 60 years. You can’t really condense that. You can’t ever really do that justice in a way. But I think we pulled some of his great stories and brought them to life with archival and with great secondary interviews in a way that surprised him.