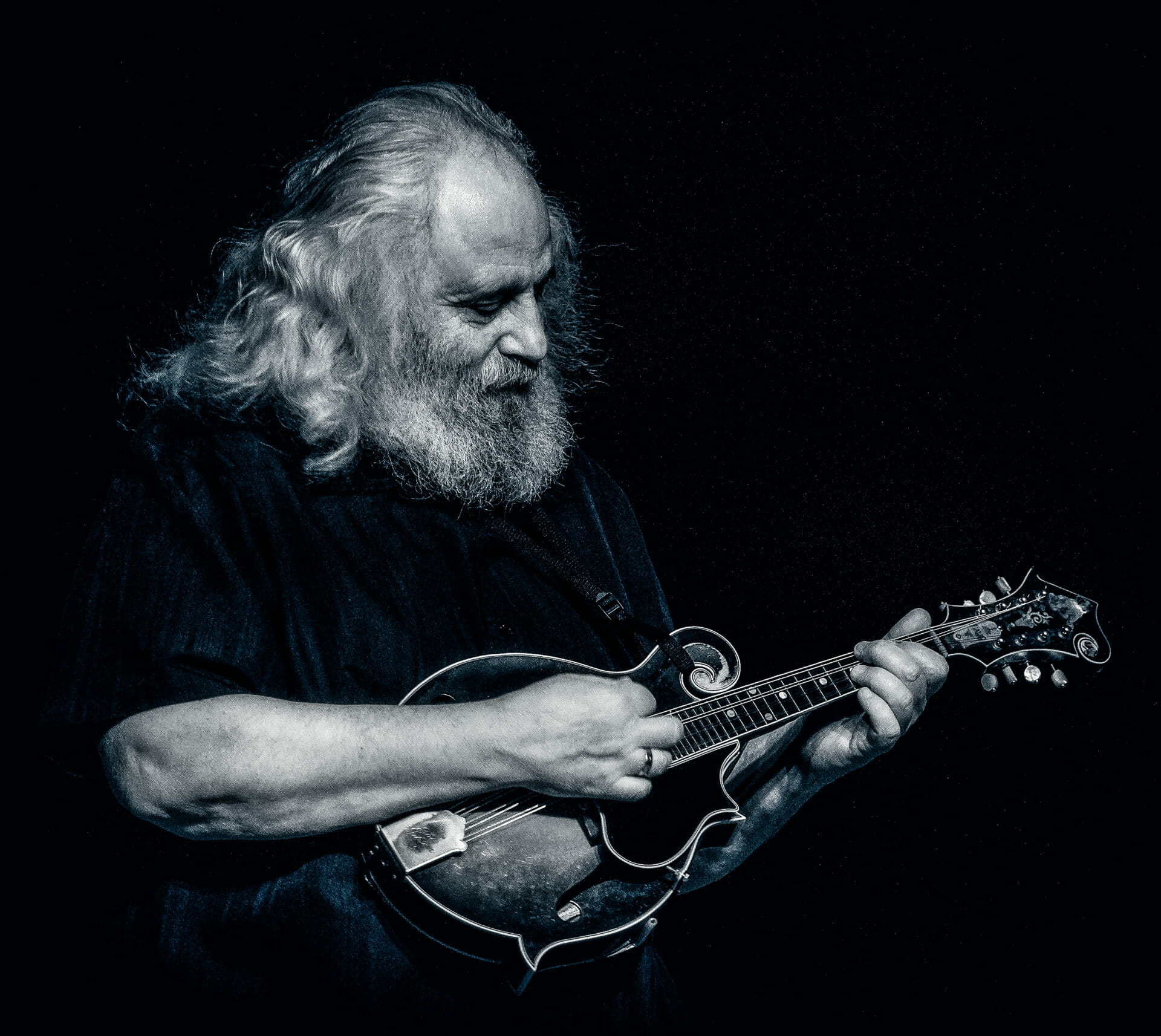

Dawg Tales: David Grisman on Jerry Garcia, Tony Rice, Danny Barnes and Three Decades of Acoustic Disc

“It wasn’t part of any kind of master plan,” David Grisman says of the decision to launch the Acoustic Disc label in 1990. At that point in his career, the renowned mandolin player and composer had already been recording and producing music for 27 years, initially as a member of the Even Dozen Jug Band (whose roster included John Sebastian, Maria Muldaur, Steve Katz and Stefan Grossman) and later fronting groups such as the David Grisman Quintet (a project that also featured Tony Rice, Mark O’Connor, Mike Marshall, Darol Anger and others).

“My two friends, Artie and Harriet Rose, had decided to move to the Bay Area and start a business,” he continues. “At first, they wanted to start a CD store, and I helped them look into that. But we realized pretty early on that it wasn’t feasible to start competing with Tower Records. They’d have to tie a whole bunch of money into inventory and selling CDs for practically what you had to buy them for.

“Around the same time, I got dropped by MCA for failing to sell 25,000 copies of a record called Svingin’ With Svend—it only sold 19,000 copies in nine months. They had a clause in my contract that allowed them to drop me. They said that if I wanted a six-week extension before they let me go, I could send them a demo of what I was planning to do for my next album. I told them, ‘I think you can imagine.’ [Laughs.] But that left me with no record company, and I was ready to make a record. So we just sort of decided, ‘What the hell; let’s start a record company.’”

Acoustic Disc has released nearly 100 albums during the past three decades, starting with Grisman’s Dawg ‘90. In addition to music by the label’s co-founder, which includes five releases with Jerry Garcia, Acoustic Disc has issued recordings by artists such as Stéphane Grappelli, Vassar Clements, Rudy Cipolla, Frank Vignola, Jethro Burns and Radim Zenkl.

In 2020, when the Roses decided to retire, Grisman and his wife Tracy acquired their stake in the label, which they now run together. They have placed a particular focus online, where they offer a variety of high-definition downloads from the Acoustic Disc catalog (most of which are deluxe editions, with bonus tracks). The website also moves beyond e-commerce, sharing videos as well as the entertaining and enlightening Acoustic Encounters podcast, which Grisman co-hosts with banjoist Danny Barnes.

Acoustic Disc debuted with Dawg ‘90. Was it your intention from the outset to release music from other artists as well?

I had been producing records all along, starting with Red Allen and Frank Wakefield for Folkways in 1963. Part of that process was always dealing with a record company. So I figured it would make my job easier in that I would not have to deal with convincing somebody to let me make a record and then dealing with whatever was involved with that company. But I took it one step at a time.

I was really enamored with the music of Jacob do Bandolim, a great Brazilian mandolin player. His style is called choro. I had been turned on to that music for quite some time and had found recordings of his in Germany, Japan and various places. So that was one thing that I really wanted to do. I viewed it as a vehicle to just continue doing the kinds of projects that I’d already been doing but I wouldn’t have to ask anybody’s permission.

Looking back on it, we probably would’ve been out of business if Jerry Garcia hadn’t come into the picture. [Laughs.] I had sort of been through the record company mill and I wanted to have a COD, no-returns policy, which everybody laughed at and very few people signed on to. But when we came out with Garcia/Grisman, they all signed on. That only lasted so long anyway because I couldn’t quite reinvent the music business without sacrificing everything else I wanted to do. Of course, I don’t really know what’s going on in the music business these days despite having been doing this for 30 years. [Laughs.]

When we came into the CD business, the interest in LPs was really waning, so we decided that we would just focus on CDs. It was a new frontier because, on an LP, you could only have 22-23 minutes per side due to the physical space. But CDs extended that to just under 80 minutes. So, immediately, we started rethinking what a project could be since we could fit more music on it. I’m a fan of all this stuff so I was all for that—more music.

Did you find it challenging to compete with the existing labels when it came to signing artists or, given your focus, did you have that lane to yourself?

I never signed artists—I just did projects. I never wanted to own somebody and then force them to meet a deadline for their next one—that whole thing. I understand that’s the way it operates, but I never wanted to sign an artist.

So with Radim Zenkl, I met this kid from Czechoslovakia who had migrated to United States and he was an amazing mandolin player. He developed a bunch of tunes and different tunings and I said, “Hey, I’d be happy to record this music and put it out.” I did another record with him, but it was all voluntary.

With Bluegrass Reunion, I had just recorded with Red Allen on the Home Is Where the Heart Is session and I invited him to come over. Then, I put together a group to play some bluegrass, with people I had been playing bluegrass with through the years. [The combo included Herb Pedersen, Jim Buchanan and Jim Kerwin, with Jerry Garcia appearing on a few songs]. Rudy Cipolla made his first record when he was 82, and I produced that. There were also other things like the Andy Statman’s Songs of Our Fathers; we had collaborated on Mandolin Abstractions, which was based on the concept of playing free music on two mandolins and we forced Rounder Records to put it out. [Laughs.] The Kitchen Tapes [Red Allen and Frank Wakefield] was something that Peter Siegel and I had recorded in Frank Wakefield’s kitchen.

There was no kind of big master plan. It’s all filtered through my musical interests.

Even though you had already been a partner at Acoustic Disc for 30 years, did you make any immediate changes after the ownership transition?

During those 30 years, I was playing gigs and producing records. I had a very busy schedule and didn’t focus on the business end or even the creative side of the business end. Then, two-and-a-half years ago, our partners decided to retire. So my wife Tracy and I bought them out and took over the company at the beginning of 2020. When the pandemic hit, it gave us this perfect project to work on out of our house. I didn’t realize, when we took it over, that all my gig work would go away.

The first decision we made was to stop making CDs and focus on digital projects. Technology has handed me—and any other musician who wants to go this path—the ability able to essentially sell air. The idea of being able to sell an infinite number of something that you don’t have to manufacture is amazing.

I’m also really grateful that there’s this convenient way of making it available. It’s much easier to produce these projects without factoring in how many we need to order. A big part of the music business is the actual physical product and distributing it—having it lost, broken and returned. It’s a nightmare.

Now, we can sell music directly to somebody in Germany. They’ll get the music, we’ll get paid, nothing has to be manufactured and nothing will be destroyed. It’s a very green idea.

You mentioned Jerry Garcia earlier. You first met him at a Bill Monroe show but how did the two of you connect?

We were at that place Sunset Park in West Grove, Pa., where they had bluegrass shows in the ‘50s and ‘60s. A lot of the pickers would play in the parking lot, and that’s where we ran into each other. We hit it off and stayed in touch. That was 1964.

I had also become friends with Eric Thompson, who was a friend of Jerry’s. Eric had come to New York and sort of crashed in my apartment for a few months. We played a lot of music together. He was in the New York Ramblers when we won the Union Grove Fiddler’s Convention band contest in 1964. It was through him that I really got to know Jerry.

Then, the following summer, I made my first trip to California to visit Eric, who was living in Palo Alto in a house with Phil Lesh and David Nelson. Jerry was already married with a young daughter, but he would still come by. That’s when they were forming the Grateful Dead but they were still called The Warlocks. We hung out a lot during that time—we played music and we kept in touch. When I moved to the Bay Area at the end of ‘69, we hooked up again and, ultimately, did Old & In the Way.

Many years later, Jerry came over to my house a little while after we started the company. By that point, I had built a studio in my basement and recorded the Dawg ‘90 record. We had run into each other at a recording session [for Pete Sears’ Watchfire album] about a year earlier. It had been about 12-13 years since we had played music together, and we talked about making a date to do it again.

Then, he called me one day and I invited him over. As soon as he walked in the door, he said, “I know what we should do. We should make a record so it’ll give us an excuse to get together.” I told him: “Well, I just started a record company and I have a studio down in the basement.” He said, “Good, we’ll do it for you.” It was the easiest deal ever struck in the music business.

You followed that up two years later with Not for Kids Only. It seems like both a logical and inspired choice, but you’ve said that you faced some resistance.

Nobody liked that idea, including Jerry. But I thought it was a good one and, eventually, I roped him in. I just thought it felt natural for Jerry Garcia to sing kids’ songs. He’s such a paternal figure to so many people but, when I ran it by him, he said, “Ehhh.” Then, one day he called me up out of the blue and said, “What are you up to? I’ll be over in a few minutes.” That’s something he used to do.

On this particular day, before he came over, I was hanging out with a friend of mine, Bernard Glansbeek—he was a really a good musician who, sadly, recently passed away. I said, “Hey, Bernard, you think you can run out and find a book of children’s songs?”

So he went to a music store and came back with this book that had like 2,000 children’s songs. And when Jerry came over, I said, “Why don’t we check out a few of these songs?” He looked through it and said: “Oh, here’s ‘Freight Train.’ We could do ‘Freight Train.’” So, boom, we did it. Then, he said, “Oh, ‘Horse Named Bill,’ I know ‘Horse Named Bill.’” Then, he saw “Jenny Jenkins.” So we knocked a few of them out of the park right then because they’re simple, and we had a very natural way of playing together that didn’t involve much work, really.

Can you talk about the origins of your Tone Poems project with Tony Rice, which you’ve also released as a hi-def Deluxe Edition?

I always like records that have more than one angle because this kind of music needs every angle it can get. [Laughs.] Not for Kids Only is a kids’ record, and it’s also Jerry and Dawg. With Tone Poems, I’d been really interested in collecting vintage instruments for many years and watching that whole scene proliferate. So I had this idea for a concept record that would showcase various American-made instruments—mostly from the ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s.

I thought Tony Rice would be an ideal collaborator, and he was into it. A good friend of mine, Dexter Johnson—who had a vintage instrument shop in Carmel, Calif. called Carmel Music—helped out with getting together an enormous amount of these instruments and setting them up. I thought that was a cool idea because you can get two different markets. You can potentially get all the vintage instrument collectors and all the people who like Tony Rice and me.

Danny and I have also embarked on a banjo Tone Poems project. I’ve got some really cool banjos, and it dawned on me that Danny’s the perfect guy to do it because he’s a great banjo player and can play lots of different styles and techniques. So that’s a work in progress.

How did you come to meet Danny and collaborate with him in both the Dawg Trio and the Acoustic Encounters podcast?

We moved [from California to Washington] in 2015. My wife, Tracy knew Danny. She’s from the area, her grandparents were born here. She took me down to a local gig at the pub where Danny was playing with another friend of ours, Matt Sircely. I was aware of Danny but not really all that familiar with what he did.

After the show, we went up to say hi and he said, “You know, you played on my favorite album in the whole world.” I asked him which one, and he said Don Stover. I had the great fortune to make Don’s first album Things in Life. That surprised me, so I invited him over. We really hit it off and he was interested in learning my tunes.

Then, maybe four years ago, Peter Rowan had to cancel his appearance at Wintergrass in Bellevue, Wash. at the last minute due to some health issues. So Steve Ruffo, who runs that festival, called me up and asked me if I could put something together. That’s how the Dawg Trio started. Danny and I had been getting together for maybe six months before that. My son Sam came up here and we rehearsed for a couple of days, played two sets at that festival and then kept going.

It’s a great thing because there isn’t any aspect of what I do that this combination can’t play. I’ve done a lot of duets and, even with adding a bass, it still has that small ensemble intimate thing. But we can also play bluegrass. We can sing trios, we can play swing, jazz— you name it.

It’s been a real joy for me to have Danny as a collaborator, friend and neighbor. He’s a big reason why I’ve written 15 tunes in the past two years. After the first hundred, I thought I was pretty much finished because I wondered if I’d run out of ideas. But he’s kept me going. He knows bluegrass and he knows a hundred other styles of music really deeply. He is just a kindred spirit. So we have a great time.

I had the idea to do something called Acoustic Encounters a number of years ago. I recorded some conversations with people like Andy Statman and Mike Marshall. They would come over and then we’d play some music. I still have those somewhere, but I never did anything with them. Then, when I met Danny, we’d just talk about music and all kinds of stuff, so it struck me to put it in this form.

On the first episode of your podcast, you share some wonderful stories about Ralph Rinzler, who lived in Passaic, N.J. where you grow up. Rinzler was a musician, promoter and manager before becoming the founding director of the Smithsonian’s Festival of American Folklife. If you hadn’t met him, do you think you would have pursued a similar musical path?

I have thought about that, and it’s hard to say. I had already started to discover bluegrass and folk music by then but spending time with him was definitely like going from the ground floor to the penthouse. He was four blocks away. Three of us young misfits would walk by his house, and this guy was such a fountain of knowledge. I can’t say enough about Ralph. He was such a wonderful guy. In the podcast, I told Danny about my mom being his art teacher.

Ralph eventually realized that he wanted to be behind the scenes to boost the music that he loved. He didn’t feel comfortable being an entertainer. He thought he could be more useful promoting Bill Monroe and authentic kinds of folk music.

You recently started acquiring the rights to your pre-Acoustic Disc catalog. You just released a Deluxe Edition of your 1964 album, Early Dawg. Was that something you’d been thinking about for a while?

My manager Craig Miller—we’ve been together since around ‘75—obtained the digital rights to Early Dawg, Mandolin Abstractions and my Christmas album. That was on my list of to-dos, and I’ve been expanding a lot of these projects and calling them Deluxe Editions because I have additional material. I usually record more than I use for any given project. So I have lots of different takes and tunes that were left over from various projects.

I’d been thinking about extra stuff for Early Dawg and, within the past year, a guy named Dick Abrams sent me a CD of a jam session that he recorded on a cassette in his living room in May of 1964. I didn’t even remember the session but it was Bill Keith (banjo), Fred Weisz (guitar) and me. I ultimately got him to send me the actual cassette and I had it transferred as best I could. I’m using four tracks from that jam session, one of which is the first recording I could find of my very first tune.

There also was an album I made with New York Ramblers, the band I was in, some time in 1965. We stayed up all night at the Columbia University radio station, where my friend Robert Gurland had a radio show. He was in the Even Dozen Jug Band at the time. My friend Peter Siegel produced the session. I’m using four tracks that have never been released.

I also found some takes that weren’t issued from a concert that Del and Jerry McCoury and I played with Winnie Winston, the banjo player.

The original release had 16 tracks, and this one has 30. It’s either historical or hysterical, but if somebody wants it, then here it is. [Laughs.]

You’ve also just released a 1976 live performance by Stéphane Grappelli with the Diz Disley Trio. Can you talk about that?

I think Stéphane Grappelli is one of the most amazing musicians ever. I am just so fortunate to have played with him and been able to know him. This was on his second tour of the Bay Area in the same year. I was floored by this band, and I got a chance to obtain the tape from Lee Brenkman, who was the soundman at the Great American Music Hall.

It’s an amazing band. Diz Disley was quite a character— a fine guitar player and kind of a raconteur. Ike Isaacs is a legendary jazz guitar player. And Brian Torff was a very young, talented bass player at the time.

It’s just a fabulous live recording of two complete shows. Stéphane’s music really inspired me. The first time I heard him play, it just took my breath away. Think about how many violin players there are in the world. Yet, you can still hear only a couple of notes and know it’s him. It’s just amazing music.

What else is on the horizon for Acoustic Disc?

Dix Bruce, who used to help me with the Mandolin World News, made a tape of Tiny Moore playing with a jazz trio back in 1980. It’s great stuff and I’m into promoting real music. I’m having a ball doing this, and my wife is handling the business side of things. She’s a really great artist and quite a fine musician, too.

I also have a lot of projects of my own that are potentially in the works to be released, going back weeks or decades. I’ve done some recording with Danny and Sam, and I’m always accumulating different recordings. I have all kinds of live archives. I did a session with John Hartford just for fun once. Since I had my own studio, I recorded for kicks. Hartford was playing a gig in Mill Valley for two nights, and he came over and we just spent an afternoon playing duets together. I released one track on that Life of Sorrow album, but that’s a project.

There’s a lot of stuff that people have never heard. I have a lot of things, so I’m always asking myself: “What am I gonna do next?”