Behind The Scene: Danny Zelisko

Danny Zelisko and Bill Graham at Las Vegas, Nev.’s Sam Boyd Stadium, April 1991

“This was the field that chose me,” declares promoter Danny Zelisko, who was only two years out of high school when he produced his first show, a 1974 Mahavishnu Orchestra gig in Tucson, Ariz. “I wasn’t really equipped to be an electrician like my dad. I didn’t want to drive a truck, I didn’t want to work at McDonald’s. I didn’t go to college at a time when it seemed like everybody was going to college. But I found a place where I belonged because I love music and I love the people who make music. Little by little, I started meeting these people and, little by little, I started talking to agents about my favorite groups at very early stages of their careers. I would go on to work with many of them for years to come. I just love that!

“I think back to 1971 and 1972, which were really prolific concert years for me,” he continues. “In those two years, I saw so many of my favorite groups for the first time: Emerson Lake & Palmer, Yes, the Grateful Dead, King Crimson. There were so many other really great artists too, like Leo Kottke, Joy of Cooking and Jefferson Airplane. I loved those early shows because I was just a kid and a fan, and we had our pre-concert rituals like everybody else. We had a blast with it and it feels incredible to still be around music so many years later.”

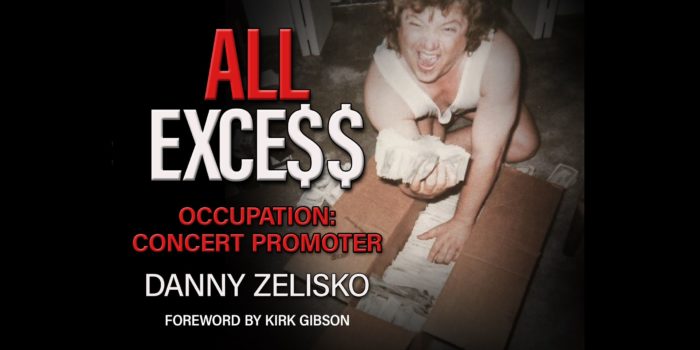

Zelisko’s enthusiasm bursts forth from the pages of his new book, ALL EXCE$$ — Occupation: Concert Promoter (which is available at dzplive.com). A spirited raconteur, Zelisko shares tales from his early days as a Chicago sports enthusiast and memorabilia collector who met numerous athletes while still in elementary school and, eventually, built relationships with the Chicago Bears’ Brian Piccolo (the subject of the heart-wrenching film Brian’s Song), “Mr. Cub” Ernie Banks and many others. As a teenager, Zelisko found his way backstage at early Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd performances, chatting up artists and crews alike.

In 1974, Zelisko relocated to Arizona and founded Evening Star Productions, initially booking shows at the 700 capacity Dooley’s Nightclub in Tempe. Zelisko became the preeminent area promoter, moving into amphitheaters and stadiums, before selling his business to SFX in 2001. He remained with the company as it transitioned from Clear Channel Entertainment to Live Nation, eventually becoming president and then chairman of Live Nation Southwest. He finally left in 2011 to resume the life of an independent promoter under the Danny Zelisko Presents shingle. ALL EXCE$$ tracks all these developments in 60 zippy, conversational chapters, supplemented by photos, posters, ticket stubs, backstage passes and other ephemera.

“I had been asked by a lot of people if I was ever going to do a book,” he says. “Over the years, I’d be sitting around just BS-ing and the stories would come out. They would be fascinating, especially to people who barely knew the subject or maybe were there, but weren’t in the room. I’m also a collector, so all the pictures and memorabilia that I’ve saved helped to tell the story.

“While we were editing the book, I was reminded that I was living on fumes for a few years there in the beginning,” he adds. “I hope that somebody reads this and understands that I started with nothing. I didn’t have money. I think the overriding message is that anybody could have done this if they had the chutzpah and the tenacity and the stupidity not to figure out: ‘You’re never going to be able to pull it off.’”

Taking COVID out of the equation, given all the developments in the live concert industry, do you think that someone growing up in Chicago today could pursue the same path that you did?

I think somebody could do it, but they should be prepared to have a lot of doors slammed in their face and to be laughed at or ignored because that’s what happened to me.

When I started out, every time I called about an act, I would hear, “You can’t get them.” When I’d say, “Why not?” I would be told, “You’ve never done a show before, we’re not going to just sell you the act. What if you screw up?” It took me getting that first show and the second show and the third show…

However, there are always going to be bands flying under the radar before anyone else pays attention to them. That’s where you’ve got to pay attention because that’s where you’ll have a chance to promote a show.

Now, if you do a bunch of shows, you’re going to start relationships with the bigger agents that have the more established, bigger bands. And if you do your job right, then you’re going to attract their attention.

Another piece of advice is to find a place where nobody else is. All you need is a good venue and some money because you need to put down deposits and buy advertising.

When I came here to Phoenix, there were 700,000 people, not 6 million. So there was one promoter here and then other people dipped into the market for certain shows. For instance, people in Southern California would come in here and do a show as an extra date around their main city because there was nobody really active in this territory until me, and that took years to accomplish.

So someone could do it today, I’d just recommend doing it somewhere where there isn’t a main independent or corporate promoter.

At the end of the night, during your very first show with Mahavishnu, did you know how to do the settlement? And how long did it take you to figure out the other particulars of promoting shows?

There was no settlement because the show only drew a thousand people. So they were happy to get their guarantee out of it. [Laughs.]

I had a sense of what was going on but there was also a lot of finding my way through a room in the dark, feeling as I went. I knew that I had to make a deal with the artists and that I had to make a deal with the hall. Then I’d get the artist’s rider, which was a real eye-opener—I had no idea.

I knew the mechanics of calling up a radio station and ordering commercials, getting prices on those. But as far as budgeting, nowadays, we carefully put out a pro forma offer for each show that lays out what we’re willing to spend on certain line items or what we’re anticipating. Back then, I had nothing like that. I often went over those on the phone with somebody. It might take an hour to make an offer. My phone bills once things really started cooking in the late ‘70s, through the ‘80s and ‘90s, were like $7,500 a month. We had 10 people working on WATS lines. I’m happy those costs have come down. If you think about it, that’s one of the very few things in the world where the cost for doing what we do went backward instead of getting more expensive. It seems like everything else stayed the same or went higher—whether it’s wages or gasoline or advertising. Everything got more expensive.

You did shows with Van Halen during the time when they had that provision in their rider requiring a bowl of M&Ms with the brown ones removed. Did you comply?

We did, indeed. Of course, they did that to make sure promoters were reading the rider. Then if they got there and they saw brown M&Ms, they figured the rest of the day was going to be shit and they’d make your life hell for it. Thankfully, we knew better. I actually did those shows with Brian Murphy from Avalon [in Los Angeles]. He had the relationship with Van Halen but he didn’t want to do the show all by himself over here. We had several Coliseum shows with the original lineup but I was warned about all this from the outset by Brian. He even had his own production manager come over here and do the show. He didn’t trust me by myself.

In your book, you describe the Grateful Dead as the group that “set the standard that all others will forever be compared to, both as a band in this business and a force in our world.” Can you talk about your relationship with them?

That was another great eye-opener. In the ‘70s, I got to do club shows with Jerry—I did Reconstruction. And, then I started doing shows with Bobby in the very late ‘80s. These were at nightclubs or small halls where they would play with their solo endeavors. Of course, when I got close to these guys, on the night of the show, I’d always go, “Hey, how about some Dead action?” [Laughs.]

But they had their setup, which was: Bill Graham west of the Mississippi and John Scher east of the Mississippi. It was very difficult to break into that. The Dead were not like a normal band, and the Bill Graham people and the John Scher people understood the way that they worked. No band had tailgating like they did or that parking lot scene; the potential camping, drugs and everything else that went along with that was unique to them. But those guys knew how to manage it, so the Dead stuck with those two guys, basically.

Finally, in ‘87, after being around Bill a bit—though we weren’t friends yet or hanging out the way we eventually did—I got that first show at Compton Terrace. Bill came out for it and he was amazed and so impressed that I got 17,000 people to come to the show. They’d never done more than 6,000 people here before; although they hadn’t been here in a long time, which also aided my ability to draw more people. It worked like a charm.

It was great to see Bobby and Jerry and remind them that I had never done a Dead show before. I had been to shows and I’d seen them at those, but I was a guest. I wasn’t the guy doing everything. They were truly remarkable, the way they had it together. I don’t think they set out to be promoters, either. They just wanted to be a band and things happened for them—the acid tests and everything in the ‘60—so their fame and mystery grew. By the time the Dead came to Compton Terrace in ‘87, they had their system down. People could buy tickets directly from the band through the mail. So they were a box office, they were a promoter and their people ran the shows, production-wise, with the local production manager. Pound for pound, they were probably the most complete, together touring unit ever.

You became quite friendly with Bill Graham. What do you think is misunderstood or underappreciated about him?

Bill was a rough-and-tumble kind of a guy. But I always remember him thinking about his audience and defending his audience. He would become very angry if a band went on late or if they were terribly fucked up and couldn’t perform but wanted to go out anyway. And, he never carried himself like, “I invented this business.” It was always just about right and wrong with him.

Bill passed away when he was 60; I’m 10 percent older than that right now. But by the end, I felt like he was getting tired of just the whole consolidation aspect of things—how everything was becoming very corporate. There were a lot of people who came into the business after him that maybe didn’t care about certain aspects or techniques that he employed. I think that might have offended him because he did write the book on a lot of this stuff.

The bottom line is: First and foremost, he liked who he was. He was comfortable in his own skin. He walked around shows like he owned the place because he did. But he was one of the most approachable people by fans that I ever met. I don’t think I was ever as good at that as him and I like to think that I’m pretty good at it.

If there was a problem—if there was a spill on the floor—he was the first guy to run for the mop.

In ALL EXCE$$, you also describe the time you riffed names for Lollapalooza with Perry Farrell. It sounds like he nearly went with Jamboree, which doesn’t seem like an ideal fit.

He wasn’t saying, “I want to call it a jamboree;” he was trying to come up with a word that suggested a gleeful, old-fashioned circus-like atmosphere surrounding a concert.

The conversation was very late at night. We were hanging out for a few hours after a show at the hotel. Perry was looking for one of those cozy, time-tested terms that suggests a certain feeling, or a certain description of what’s going to take place. We definitely bantered for a while and, by the time we were done talking, that was the word. The Lollapalooza name just came up, and I don’t think he could have come up with a better word than that.

If I asked you to name one of your past shows that evokes a pleasant memory, what’s the first one that pops into your head?

This has been such a weird year for everything, and I lost one of the people I was closest to—John Prine. We were brothers. I think of the last show I did with him in 2018. I didn’t have any shows with him last year. We took a year off in between plays—nobody had any idea that he wasn’t going to be around.

Over the course of my career, I did more shows with John than anybody. But, after I went with SFX 20 years ago, John started having to work with so many other people because SFX wouldn’t let me promote John outside of my own markets. Had I known that when I made the deal, I would have told them to keep their money. That’s how much I love John. Unfortunately, I wasn’t aware of that until after I made the deal with them.

I think John’s the best songwriter ever. Nobody could write words like him and nobody could make an audience feel like him. There are so many other great bands who I really love, but, if you’re going to ask me for one show from one guy, I’m going with him.