Apocalypse Prophesized: Yo La Tengo, Mickey Hart, Bill Frisell and Others Honor Allen Ginsberg

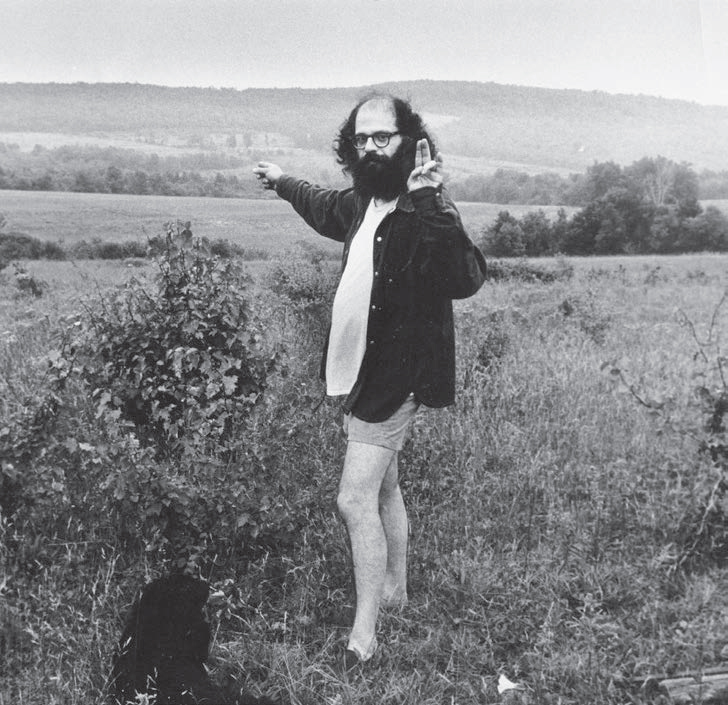

photo credit: Elsa Dorfman

**

“Apocalypse prophesied—

the Fall of America

signaled from Heaven—”

–ALLEN GINSBERG, “IRON HORSE”

Did we narrowly escape the fall of America in January or is it lurking just around the corner? It’s impossible to say, of course, but the Beat Generation poet laureate Allen Ginsberg felt he was living through his country’s precipitous decline a long half-century ago.

After traveling through Europe in the first half of 1965, Ginsberg decided to rediscover America “during an era of hallucination and war.” He hoped to creatively come to grips with the country’s splendors and evils—most notably the Vietnam War—through travel. And so, while crisscrossing the country with a self-imposed mandate to write a “long poem of these states,” he composed the spectacular verses collected in The Fall of America: Poems of These States, 1965-1971, which won a National Book Award for Poetry following its 1973 publication by City Lights.

Ginsberg was both a social force and literary phenomenon, and his influence still looms large. Devendra Banhart, Andrew Bird, Bill Frisell, Mickey Hart, Handsome Family, Angélique Kidjo and Yo La Tengo are among the more than 20 artists who interpret, embellish and reimagine Ginsberg’s personal, political and universal visions on Allen Ginsberg’s The Fall of America: A Fiftieth Anniversary Tribute, available as an LP or a longer CD via Bandcamp. Peter Hale and Jesse Goodman of the Allen Ginsberg Project, the online manifestation of the Allen Ginsberg Estate, produced it.

Hale—who worked with Ginsberg for five years prior to the poet’s death from liver cancer in 1997—describes himself as the estate’s “man on the ground.” Initially, he says, the project’s mandate was to keep Allen’s published works alive and publish what unpublished works remain. “And now we do websites and social media,” he adds.

The Allen Ginsberg Project has shepherded a couple of movies including Howl, the 2010 biopic starring James Franco as Ginsberg, and has signed off on other audio projects. Hale and Goodman have also produced numerous concerts at the Henry Miller Library in Big Sur, Calif.; Laurie Anderson, Arcade Fire, Fleet Foxes and Yo La Tengo have all performed, with Beat poets like Anne Waldman and Joanne Kyger serving as their opening acts. The Fall tribute, though, is the Project’s first self-initiated release.

“Sharing as much as possible is the ethos behind everything we do,” Hale says. “Nowadays, we’re overwhelmed by information. But I still think that making available as much of Allen’s work as possible lets you see how much cool stuff is there, and how many dots you can connect in regard to the countercultural linchpin he certainly was. It’s so much fun, and a never-ending source of inspiration.”

“Peter often says, ‘No matter how many years have passed since his death, Allen is the gift that keeps on giving.’” Goodman adds. “His force was so strong.”

And speaking of linchpins: In late 1965, Bob Dylan gave Ginsberg a gift that would dramatically alter the beat poet’s artistic trajectory. With the songwriter’s $600—equivalent to about $5,000 today—Ginsberg purchased a cutting-edge reel[1]to-reel Uher tape recorder. He packed it up and took it along to record the kind of spontaneously improvised impressions—or, in his words, “auto poesy”—that he admired in Neal Cassady’s epistolary fireworks and Jack Kerouac’s 1957 roman[1]à-clef best seller, On the Road.

Ginsberg took to the tape recorder with much of the same zeal as he embraced photography: It was a way to preserve the sacred, or merely social, moment. (Check out The Fall of America Journals, 1965-1971 for the raw auto poesy Ginsberg transformed into bejeweled verse.) It also helped him capture the music flowing within his words, which he often accompanied with his own droning onstage harmonium.

As a fan, Ginsberg appeared to prefer rock to the jazz beloved by his Beat contemporaries. As he wrote in September 1965 after seeing The Beatles perform in Portland, Ore., “Frank Sinatra lamenting distant years, old sad voic’d September’d recordings, and Beatles crying Help! their voices woodling for tenderness.” He was The Beatles’ favorite beat writer, too; there he is on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Both The Beatles and The Beach Boys received extra credit from Ginsberg for practicing Transcendental Meditation.

Arguably no other poet—Nobel Prize-winning Bob Dylan being beyond categories in this regard—has enjoyed a wider variety of contemporary musical interpretations than Ginsberg, whose words have been interpreted by and/or inspired Paul McCartney, The Clash, Patti Smith, Phil Ochs, The Fugs and composer Philip Glass, who wrote music for Howl and Wichita Vortex Sutra.

Most significantly, the late producer Hal Willner released two remarkable volumes of Ginsberg recordings. The Lion for Real (1989) set Ginsberg’s poetry to loose-limbed Downtown-jazz interpretations, while the four-volume Holy Soul Jelly Roll (1994) offers the largest collection of Ginsberg reading his own work to date.

The Fall of America tribute is dedicated to Willner, an early American victim of COVID-19 who died in April 2020. Having been inspired by Willner’s own eclectic tribute projects—including concept albums dedicated to Italian film composer Nino Rota, jazz legends Charlie Mingus and Thelonious Monk, vintage Disney films, and not one but two collections of pirate ballads and now inexplicably trendy sea shanties—Hale and Goodman hoped to enlist their friend’s assistance.

“I had dinner with him last February,” Hale says. “But I told Jesse: ‘Let’s not bring the tribute up with Hal until we get our ducks in a row.’ And then—boom!—it was like out of the blue.

Bill Frisell, who fronts an ensemble on two of Willner’s Lion for Real tracks, returns on The Fall of America in full-sailed, graceful solo glory. His interpretation of “Over Laramie,” in which Ginsberg segues from the personal (“Look out on Denver, Allen/ Mourn Neal no more/ Old ghost loves departed”) to the tectonic, transports the guitarist back to his Rocky Mountain roots. “Frisell told us: ‘I grew up in Denver and I can smell the trees when I read it,’” Hale says. “His guitar’s so sweet. You feel like Allen’s following him rather than the other way around.”

It turns out that the Ginsberg-Willner nexus plays an even larger part in Frisell’s musical history. Frisell appreciated the constellation of local landmarks he recognized in On the Road. “Neal Cassady went to my high school,” he says, “but I don’t think he stayed long. I could picture exactly where those guys [Kerouac and Cassady] were, though. They talk about Neal’s father on Larimer Street. That’s where all the bums and pawn shops were, and I’d go there to look at guitars. And we’d drive up to Laramie, Wyo., for gigs. So my Denver nostalgia is triggered all over the place by that poem.”

Frisell met Ginsberg soon after the guitarist first arrived in New York. The poet recited Howl one afternoon as Frisell jammed wildly in a Chelsea rehearsal studio with a pianist friend, Victor Godsey. But an even stronger connection emerged when he began working with Willner.

“I got my first electric guitar in the summer of ‘65,” says Frisell, calling from his Brooklyn home. “So pretty soon I’m playing along with records and this Marianne Faithfull song, ‘As Tears Go By,’ comes out. I clearly recall that it was one of the first songs I learned by playing along with a record. Like, ‘Oh, wow! I figured out the chords!’ I was so proud of myself.” Twenty years later, Frisell found himself recording the same song alongside Faithfull, with Willner producing and Ginsberg sitting in the control room.

After The Lion for Real, Willner invited Frisell to participate in an even more extensive Ginsberg project based on the poet’s book-length Kaddish, written about the 1956 death of his mother, Naomi, and published in 1961. “It was a big deal for me,” Frisell says. “Like everything with Hal, he presented me with a mind-blowing challenge/opportunity. He said, ‘Would you write music for this? But I don’t want you to play guitar.’ That was huge, because he was acknowledging that I actually do write music. It was the first time anyone had asked me to do that.”

Hale and Goodman mostly took a hands-off approach, letting the universe decide when it came to who would adapt which poem for the tribute. That’s how they ended up with three versions of the haunted and apocalyptic “Death on All Fronts,” which finds Ginsberg dreading “Earth Cities poisoned at war, my art hopeless/ Mind fragmented—and still abstract—Pain in left temple living death.” Gavin Friday and Howie B bring all the pain in their powerfully detailed full-bodied version, while Lang Lee sings Ginsberg’s blues in Korean and accompanies herself on cello. Cincinnati indie-rockers Why?’s version is on hold for volume two.

“With some artists, we had no idea what track they’d chosen until they delivered it,” Goodman says. “They were like birthday presents for Peter and me.”

Hale and Goodman only asked a single group—Yo La Tengo—to interpret a specific poem not of their choosing. In “Bayonne Entering NYC,” Ginsberg describes the drive through Newark, where he was born in 1926, past a “Megalopolis with burning factories,” and on into Manhattan, where he snags a sweet parking space in Greenwich Village. As longtime residents of Hoboken, N.J., Yo La Tengo’s Ira Kaplan and Georgia Hubley could relate. Their dramatically thrumming backdrop blends East Coast sprawl with cosmic consciousness.

Kaplan doesn’t recall if the trio recorded the basic track with or without the poem in mind, but it was ultimately overdubbed and mixed in conjunction with Ginsberg’s reading. “We’ve spent a substantial portion of our pandemic get-togethers playing long drone-based music,” he says via email. “And although it’s never been articulated this way by us, anyone who wanted to suggest that that’s been a sort of group meditation would get no argument from me.” The track’s harmonium, he adds, pays “direct homage” to Ginsberg’s preferred self[1]accompaniment.

Mickey Hart unleashes a mighty electronic buzz of his own on “First Party at Ken Kesey’s With Hell’s Angels (Drones du Jour).” He created it on The Beam, a eight-foot-long aluminum I-beam strung with 13 bass piano strings all tuned to D, the mathematically determined Pythagorean monochord. “The Om is the seed sound of all creation,” Hart says.

The Fall of America is about travel, motion and freedom, from the West to East Coasts and back again. So it’s ironic that this tribute to Ginsberg’s auto-poetic peregrinations by train, bus, car and plane was produced during a period when very few people were going anywhere at all.

In fact, Goodman, believes this album could have been created only during our global time-out. “The two go hand[1]in-hand,” he says. “When we began approaching musicians last March, they understandably freaked out. But once people settled into the new reality, it allowed for someone like Angélique Kidjo to record in her Paris studio.”

The Beninese-American singer[1]songwriter addresses our other global crisis with her interpretation of “Ayers Rock/Uluru Song,” which Ginsberg wrote in early 1972 during a trip to Australia. “I was shocked by how contemporary it felt,” Kidjo said in an email. “The Ayers Rock becomes a symbol of the wound our earth is bearing due to climate change.” Ginsberg was all about global consciousness, of course, as indicated by Planet News, the collection he published prior to The Fall of America.

“I’m working on an afrobeats album and my drum machine was full of those uplifting grooves,” Kidjo writes. “When I slowed them down to fit the poem’s tempo, it suddenly sounded like trip[1]hop meeting African dance! We added vintage keyboards as a tribute to the ‘70s. The song is open-ended because only the future knows if we’ll be able to address the climate challenge.”

Among Fall of America’s musical interpretations, only producer and Killing Joke co-founder Youth’s “Iron Horse” grapples with its source material on a scale equal to Ginsberg’s longer poems. A digital bonus single for the tribute’s vinyl consumers, “Iron Horse” is a 32-minute psychedelic epic that annotates and amplifies Ginsberg’s cross[1]country train trip with approximately 200 layers of stream-of-consciousness grooves, electronics and samples over lines like these:

“Click of train/ eyes closed … the long green courthouse building/ “Like a monster with many eyes.”/ On valley balcony overlooking Bay Bridge,/ a horse in leafy corral…/ 600 Cong Death Toll this week”

As Youth sat with closed eyes listening to Ginsberg recite “Iron Horse,” he saw “a widescreen movie unfold in my mind’s eye as the words tumbled out of the speaker in a psychedelic waterfall of inspired commentary; both inner and outer realities conveyed with authenticity and authority.” Youth also worked remotely at his own Space Mountain studio, located in Spain’s Sierra Nevada mountain range.

He started with harmonium—“of course,” he says—and then, as he relates in an expansive email, began “abstracting, subtracting, destroying, removing, adding, spinning broken records, DJ’ing cuts of found sound, weird loops, analog synths and possibly even a kitchen sink.” Former Bananarama singer Siobhan Fahey, whom he was producing at the time, “kindly took up the challenge to my invitation to sing some of the words as a haunting refrain. She does this within a structure of an ancient traditional Irish melody that has a particular magical, mystical and melancholic quality.”

Ginsberg bore equal amounts of hope and despair about America in his heart. Near the middle of his years[1]long American odyssey, he experienced the Chicago Police riot of Aug. 28, 1968, during the Democratic National Convention. Along with Fugs member Ed Sanders—who begins his simple acoustic Woodstock-windowsill rendition of “Memory Gardens” on the tribute album with a touching historic preamble— Allen, at one point, chanted “OM” while leading demonstrators away from some serious blue-line violence. Another riot, this time in Washington, D.C., recently demonstrated just how much the USA could still use a long, cleansing OM.

Does history simply spin around in circles? Maybe so, maybe not. The Fall of America tribute’s profits will benefit the nonprofit HeadCount, a nonpartisan organization that has registered more than a million voters, mostly at concerts, since 2004. As a Deadhead and Phish fan (“to put it mildly,” he adds regarding the latter), Goodman felt that HeadCount reflected precisely what Fall of America wants to convey, while Hale deems HeadCount “the antidote and solution to the American fall we’re living through.”