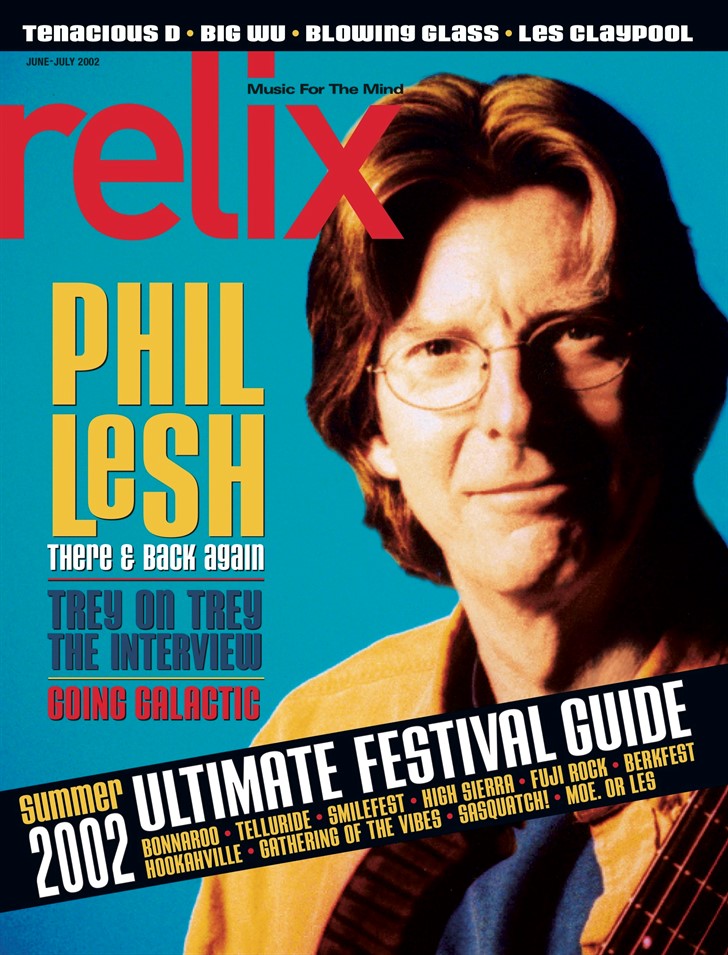

20 Years of Phil & Friends: Revisiting Our 2002 Interview with Phil Lesh

Jay Blakesberg

Jay Blakesberg

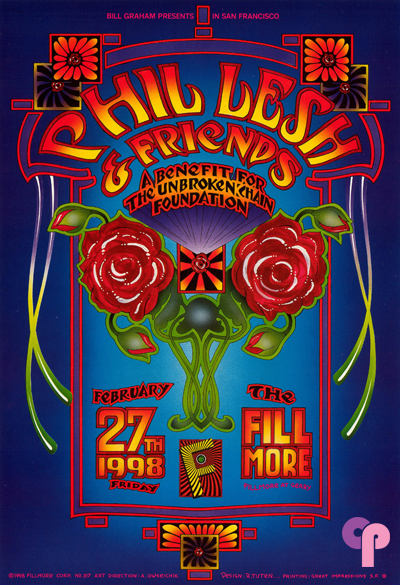

On February 27, 1998, Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh gathered a group of musicians for a benefit concert at The Fillmore in San Francisco, including Jeff Chimenti, Dave Ellis, Stan Franks, and Jay Lane, along with his longtime bandmate Bob Weir. The show—the first of several such gatherings that year—is now considered the birth of Phil & Friends, the revolving-door band that Lesh has played with countless times in the two decades since (Lesh used the Phil & Friends moniker for a show in 1994, but that basically amounted to an acoustic Dead performance, as opposed to the Phil & Friends format of 1998 through today). In celebration of the recent landmark anniversary—and Lesh’s current duo tour with Weir—we dug into the archives to present an interview with Lesh from the June/July 2002 issue of Relix, in which the bassist discusses forming the rotating Friends lineup, his health scare and subsequent liver transplant, continuing to play Dead music after the death of Jerry Garcia and releasing his first solo album There and Back Again with his Quintet lineup of Warren Haynes, Jimmy Herring, Rob Barraco and John Molo—among other topics.

When the Grateful Dead folded in 1995, bassist Phil Lesh was happy to be able to spend some time at home with his kids. But the music wouldn’t let him rest. He started doing benefit shows as Phil Lesh and Friends, playing Dead tunes with various Bay Area musicians. Eventually, guitarist Bob Weir, drummer Mickey Hart, pianist Bruce Hornsby and Lesh regrouped as the Other Ones, and in 1998 they toured with guitarists Steve Kimock and Mark Karan, jazz sax whiz Dave Ellis, and drummer John Molo, to great success.

The party was cut short by Lesh’s near-fatal brush with hepatitis C, which had irreparably damaged his liver and sent him into the hospital later that year for liver transplant surgery.

Lesh emerged from illness with a new set of priorities, including a mission to champion organ donors and transplant programs. Four months later, Phish guitarists Trey Anastasio and keyboardist Page McConnell joined “Phil and Phriends” for three shows in San Francisco, busting some old warhorse tunes out of a thirty-year drydock and helping Lesh realize that the music could never stop.

When business and creative differences arose among Lesh and his former Dead bandmates, Lesh continued on his own trajectory, establishing Phil Lesh and friends as a nexus for musicians from both the good ol’ psychedelic rock school and the young, blossoming “jamband” scene, which the Dead’s improvisational aesthetic had spawned. Lesh pursued the spaces between lyrics with a revolving-door lineup that included members of Hot Tuna, Little Feat, the String Cheese Incident, Galactic, moe. and more. The lineup solidified in 1999, with guitarists Warren Haynes (Allman Brothers Band, Gov’t Mule) and Jimmy Herring (Aquarium Rescue Unit, Allman Brothers Band), keyboardist Rob Barraco (Zen Tricksters) and Molo (Bruce Hornsby, the Other Ones). Contact with the next generation of Dead-influenced musicians reinformed the music and reinvigorated Lesh.

After thirty years, with the Grateful Dead – and nearly seven years without – Lesh has released There and Back Again, his first-ever solo album, which is really a collaboration among the band members. The disc sounds like nothing that has come out of the Dead camp before. Its tightly-produced rock sound spans reggae, honky-tonk, southern rock, avant-garde jazz and even 18th-century polyphonic church music, a la J.S. Bach – occasionally calling up Zappa, Phish, Dire Straits and even Queen.

Kicking back on a couch, in an empty house, high atop a hill overlooking San Francisco Bay, Lesh talked about the journey – and dropped a few hints about what may turn out to be a great summer to be a Deadhead.

This is the first ever Phil Lesh album. Do you see a common vein of ideas running through these songs?

Everything I’m doing these days reflects the image of a journey – you know, life’s journey. The journey to spiritual awakening, shall we say? What I’ve tried to do with the sets we play live is create a set and then a show and, occasionally, a whole tour that tells a story or describes a journey, because music evolves over time and takes you with it and, in a way, mimics your thought processes and emotions. We tried to do a thing last summer where, over 30 shows, at seven of them we played music sequenced to describe the teaching of the soul’s ascent through the planetary spheres after death. That’s kind of my central metaphor at this time – the journey – and that’s reflected in this album. Each one of these songs is like a little mini-drama, and I think we’ve been very successful in creating an uninterrupted flow; there’s no wasted motion, no noodling. They are little compositions, each one of ‘em. They have a beginning, a middle, an end – they tell a story and the sequencing of the album tells a story.

How do you go about getting a set to tell a story?

There are three levels. There’s the story the music creates (the story the keys create), the story the grooves create, and sometimes it ends up so the story the lyrics create is the main story and sometimes the music is complementary to it. On a good night I can make it so that all three of these things complement each other perfectly. It’s more of a subliminal effect on the audience than anything else. People come up after the show and say, “Thanks for that great story.” It gets in their astral body somehow. Then you’ll see them on the internet, writing about it.

Do you ever think, “Wow, they really got it?”

Oh, yeah. In fact, when we did the planetary thing last summer, there were a couple of guys who were digging into that and deriving numerological correspondences and all this nutty, occult stuff – stuff I never put in there.

Or at least you didn’t consciously put it in.

Not consciously, no. it’s like James Joyce said about Ulysses: “I put enough in there, they’ll be arguing about it for a hundred years.” And I think that’s one of the things I’d like to try to do.

It sounds like a lot of work is going into the album.

It’s like a coalescence of lighter materials that gravity pulls together to form a star. That’s sort of what this band is like to me. It’s been together now for about eighteen months and it’s amazing how each time we play, we raise the bar for ourselves. Part of that process has been creating new material. We all felt that this material was so strong that we wanted to put it out so people would know what it is, and so that when we played it in concert, they would have some grasp of it. They could sort of sit home and study it.

How do those two approaches differ? The approach of “Let’s let this song grow organically, live, into what it’s going to be, and then set it down in wax” or the idea of “Let’s make an object first and throw it out there and see what else it becomes?”

We’ve used both approaches. Grateful Dead, of course, always let the songs evolve live – sometimes for eight years or longer – before they’d be recorded. This material – my songs and one of Warren’s songs – were in rotation starting last spring so they evolved to a certain point but they also had a structure before we even started playing them. When we got into the studio, some of that had to change. Jimmy’s tune, “Again and Again,” we sort of Frankensteined it. We took it apart and put it back together in a different sequence than we had originally played. So we actually used more than those two approaches.

The technology informed the songwriting process.

We ended up using it as a compositional tool in several instances where we’d say, “Gee, this arrangement is not satisfying. It’s not entertaining me right here. What can we do?” So we would move things around and listen to the result and say, “Okay, that’s good there, let’s try this over here.” Then we’d go out and play it that way. So everything you hear is not [only] the result of moving things around in [the digital recording program] ProTools, it’s the result of us learning or experimenting and then going out and playing that sequence, that arrangement, live. I was not fond of working in the studio in the past but this experience just makes me want to make more records.

It’s a different trip being in the studio with these guys than being in the studio with the Dead.

Very much so. Mainly, I have to say, because of the technology.

Would Dead albums have sounded different – or – would there have been one more Dead album if you had had these tools?

Hard to say, hard to say. In ’95 we actually tried. We had twelve songs. We were playing the songs live. Everybody had one. Vince had two, I had two, Bob had three, Jerry had – I don’t know, whatever the rest is. It just never happened.

What was the day like when you found out Jerry had died?

I was taking my son to summer camp, and I got the call. I think my first reaction was “Well, now I can stay home with my kids.” As you can imagine, the news was not entirely unexpected. In fact, I think, subconsciously, we’d all been waiting for that call for about five years. In a way, he had been slipping away for quite awhile so it wasn’t a surprise, it wasn’t a shock. It was just, well, finally – finally, the other shoe dropped. That’s not to say that I don’t think about this guy every day and I don’t miss him every day.

Did you know right away that that was the end of the band?

I think I probably knew we couldn’t go on as the Grateful Dead. It would not have been right, and everybody knew that.

Do you still feel his presence when you’re playing?

It’s not so much when I’m playing, but actually, when I was writing some songs last year, I definitely felt a connection. One of the songs sat up and said to me, “I’m a Robert Hunter song,” and this particular song was something where I felt I was channeling, in a way, a piece of Jerry’s harmonic sensibility, his sense of chord structure. I thought, “Wow, that’s neat. This sounds like Garcia a little bit in some places.” It sounds like the little quirks of harmonic motion that he would come up with.

You eventually went out as the Other Ones. Before that, it seemed like there was some feeling around for how the band would take shape.

My wife and I started a foundation, and Phil Lesh and Friends started out just doing benefits, drawing from this pool of musicians around the Bay Area familiar with Grateful Dead music. I got involved by playing a benefit over at the Ashkenaz with David Gans’ band, the Broken Angels, and I discovered there was this enormous pool of musicians who loved this music and were reinterpreting it every day. So I started doing it sort of on my own with some of these folks. Then at one point I did my Philharmonia benefit, and Bruce Hornsby came out and Bobby came out, and we sat in with David’s band at the after-party, and they asked me about coming out on the road the next year. I said, “Yeah, but let’s do a band because I don’t have a band of my own.”

That was Further 1998; then, before the next tour, you got sick. You also had said that you didn’t like the artistic direction the Other Ones seemed to be taking.

Well, I thought that if it should continue, it should really have an identity of its own, rather than just recycling old Grateful Dead material. I thought everybody should get together and write new material and perform that – along with, of course, the classic Grateful Dead material – which is, of course, what my band is doing. And Bobby’s band, too.

Why didn’t it happen like that?

I got sick, and then other things sort of interfered, other business situations interior to the Grateful Dead.

How’d you find out you were sick?

I started puking up blood. It was the first day of school for my kids, and we were eating dinner on the deck. My wife was at a meeting, so I went to the hospital. They diagnosed that I had what’s called varices in the esophagus, which is caused by backup pressure because the portal vein in the liver was completely clogged by scarring from hepatitis C. They said, “We don’t know how long this process is gonna take before you’re too sick to move but you’re going to need a liver.”

Was there a wait to get it?

Well, yes, of course. The wait is different in different areas. In major cities like San Francisco and L.A., there’re sometimes 300 people on the list. The sicker you are, the faster you get bumped to the top. Once you sign up for a liver transplant or an organ transplant, you’re on a list starting at a certain time, and you sort of accumulate hours or days or months on this list at your particular hospital or transplant center. I was at Stanford and had eight weeks, nine weeks. But you can transfer this time over to another transplant center, so that’s what we did. After we checked everything out, we went down to Jacksonville [Florida, to the Mayo Clinic].

Were you scared?

Sure. At one point, the social worker – they have a social worker who’s part of the team – she said to my wife, “I’m the one who’s gonna have to take you through the body bag stage, if it doesn’t go right.”

Did you make yourself any promises or connect with a spirituality at that time?

Well, it kind of goes with the territory. You start realizing what’s important and what’s bullshit. Watching my kids play little league ball. A sunset. Leaves floating on the water. Little, silly things. It’s important to be around to be able to see and perceive these things.

Did it take a while to get back to playing music?

When I got back to California, it was another period of recuperation. Then I just wanted to start doing something so I got a hold of Trey [Anastasio] and Page [McConnell] and we put a gig together which was really cool, really fun. We pulled out some of the old classic Grateful Dead songs that hadn’t been done in a long time. That’s when I realized that this is one of the reasons I’m still here – to continue to reinterpret this music. There is no closure. There’s not gonna be any closure. The music demands to be reinterpreted and played continually, frequently, because that’s how we made it in the first place – to be played and to be developed continually.

How did you hook up with the Phish guys? Did you know them before?

No. I heard them play, some of their live tapes, because I was looking for some peole to play this music – because the whole idea was rotating, musical chairs. I called them on the phone and said, “So, whaddya think? You wanna come out and do this for three days?” It was kind of an explosive comeback – not so much for me, but for that old music. “Viola Lee Blues” hadn’t been done in 30 years.

Did Trey and Page know most of the tunes?

Oh, yeah. They knew more than they would admit, let’s put it that way.

They’ve sort of wrestled with the idea of bearing the Grateful Dead mantle into the future. Did you talk about that with them?

A little bit. It’s a bit of a touchy subject with them, so I don’t really push it.

From there, you went and played with tons of people. You played with the Little Feat guys, you played with Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady…

At one point I had seven sets of three-day rehearsals with different personnel, just trying to create a pool of musicians that could come and go, according to various scheduling situations. It worked well for a while, until it got to be really counterproductive in that [with] the amount of energy it took to teach all the new people coming in the basic tunes, there was never really enough time or energy left to expand the repertoire. At that point, I started thinking about having a group that would stay together for a while, and the group I have now sort of fell together.

In your shows, you focus effort on furthering the mission of organ transplants and encouraging people to become organ donors.

If you needed an organ, or someone you love needed an organ and one was available, would you accept it? Of course you would. Well, fair is fair. If you’re willing to accept it, then you should be willing to be a donor, as well.

It’s a weird experience, to be in the middle of a rock concert and everybody’s yelling “Whoo!” and then you bring it down and talk about organ donations.

It’s a slice of reality because, hey, if there hadn’t been an organ donor somewhere… About a year and three months after the transplant, we got a letter, written to all the recipients, from [my donor’s] mom. The thing she said in in her letter was, “Don’t let anybody you know do anything on wheels without a helmet.” It was terribly moving, because we found out more about him. My donor told his mom (six months before his death) that if anything happened to him, he wanted his organs to go to somebody. His name’s Cody, and my new album is dedicated to him.

Did you talk to David Crosby while you were sick?

Oh, yeah. As soon as he heard I was having liver problem, he was right there. He was a brick, and [artist] Stanley Mouse, too. Both of those guys have had liver transplants and they were like pillars for me. In fact, David and I compare scars. I think mine’s prettier.

Do you feel like a different person than before?

There’s part of somebody else in me, and I’m the host for this personality that’s part of somebody else’s spirit. It’s very subtle, intangible, but there’s something that’s different. “Symbiosis” is the term, where two distinct organisms work together to survive.

After you were sick, business issues caused problems among you and your Dead mates. Was that tempered by the things that were the bullshit that fell away and the things that were important?

The thing about any organization, or like any organism I should say, like the Grateful Dead, is that it’s made up of committed, creative, passionate individuals, all of whom have highly developed and strong opinions about everything. When we were a working band, all of that individuality was channeled into a common goal: to make the music. When the band was no longer a performing entity, and it really devolved into a corporation, then that individuality started manifesting itself in different ideas about how to do things. I found myself on the opposite side of the table from everybody else. I said, “Okay,” and I went my own way and developed my own musical identity. So did each of the guys in the Grateful Dead. They all have their own bands, they’re all making music in the way they want to. I think it’s a good thing, It’s more diverse.

The wedge seemed to have been the deal to digitize the Vault for public consumption.

I felt that we should deal with the Vault ourselves and management and the remaining band members felt that they should involve investors, take it public, make a whole big separate corporation thing out of it and I just disagreed. In any event, it never happened. We finally all got together – because whatever had been going on was not working – and said, “We’ve got to change this, We’ve got to do something.” We started out by playing music together. Bobby and I got together and played and last summer RatDog opened for us and Bob sat in with my band and it was really quite nice. We had some good times playing music together, I wanted to reopen everything on that level, on a “let’s make music” level. We’re also talking about the business, and hopefully, starting to clear up some of the unfinished business.

Now that everyone had gone off and played with their own bands, there must be at least a hundred different musicians you guys have played with over the last seven years. How do those flavors come in when you play together these days?

Well, the only experience I’ve had musically has been, first, with Bob sitting in with my band, and then on New Year’s Eve Billy [Kreutzmann] and Mickey joined us, just for a set, doing old Grateful Dead material. Bobby’s playing has always been really unique, fascinating, really innovative, and it’s always a trip to play with him. That hasn’t changed, it’s too soon to tell how Billy and Mickey are going to relate to what we’re doing, because we only played one set, and it was kind of chaotic because it was New Year’s Eve. We’re looking to play some music together, all of us, and in fact, we’re getting together this very evening to talk about that, so I have high hopes and a great deal of faith that we soon will be making some music, playing together. Very soon, I think we’ll be in a rehearsal situation. Once we actually sit down and talk to one another, then it’ll all probably more ahead pretty quickly.

You’ve been working a lot with Hunter, too, writing songs – “No More Do I,” “Night of a Thousand Stars,” “Celebration,” “Rock and Roll Blues”…

That was the one that started our collaboration. He had been sort of retired at the same time. He wasn’t writing too much. So I called and said, “Bob, I’ve got this song. It’s talking to me and it’s saying ‘Hey take me to Robert Hunter.’” So I talked him into letting me bring it over, and I played that one for him and he said, “What else have you got?” In a week he had lyrics for all of them.

You have a lot of varied experience in music, being a composer as well as a stage player. How does it all tie together?

In many different ways, actually, but mostly in the way that everything is orchestrated, so that there’s always something fresh or a new development at every turn in the song, and just trying to make sure there’s enough variety and novelty manifested at those points so that the ear and the mind and the heart are drawn onward through this gesture, this experience. My vision has always been, for a recording or for a song or a performance, to have it tell a story, a complete story in one gesture that is not broken up or mitigated in any way. It’s like someone described the music of [classical composer Karl Maria von] Weber as expressing a novel in a single sigh. That’s the sort of thing I’ve always wanted to have happen, and we achieved that with the record.

I can tell you’re thrilled about this project.

Well, this band – I’m telling you. Each one of those musicians has played with me at other times, and when this group got together it was pretty spectacular, the alchemy we were able to generate. The first day we played together, we improvised for 20 minutes – it was one of those things where we started playing, developed some ideas and then it had an ending to it and we all looked at each other and asked, “What was that? Where are we? Who are we? What does this mean?”

That’s when the music tells you that these guys are the band.

It told me, it told them – you just gotta be able to hear what’s being said. ‘Cause it just spoke through us, man, it just came down. This experience in the studio, honing in on exactly what makes things work in a transition between a vocal and a chorus, or between a chorus and an instrumental, or between the chorus and the bridge, or any of those places where you really have to lead the ear and the mind and the heart onward – I imagine that affecting the way we improvise together in a very profound way. It’s going to be more transparent and more intricate at the same time. And much more exciting, because people know when to stop playing for just that three beats and let somebody else come in and take it and put their thread into the tapestry, wave their thread into the big picture. To me, it’s like the ideal of what we had with the Grateful Dead. It’s electric chamber music and Dixieland at the same time.

What does each of these guys bring to this band?

Warren Haynes is the street-smart roots guy – he’s got that raw street, gutsy, smart, ballsy approach and he brings the kind of gravity that’s really needed.

John Molo, the drummer, his knowledge of all the little sub-genres of rhythm is encyclopedic. He has the capability of creating hybrid rhythmic genres. For instance, disco and African, all in one groove. So you can move like an African, or you can move like John Travolta. The music moves in that way too, and that’s a unique gift.

Rob Barraco knows as much about old Grateful Dead material as I do, and sometimes more. In “St. Stephen,” we have this introduction and over the top of that, Rob will play the phrase that’s the introduction to the body of the song. He combines motifs and ideas in this tapestry, which is continually evolving. And Jimmy Herring, we call him “Sunshine.” Every note he plays is a poem and when you string a few of them together, it’s like an epic – but it’s all woven into what everyone else is doing.

When all of us transcend what it is that we’re bringing to the band, that’s when it really happens. When we go beyond what we all know and what we’ve been doing, and what we’re known for, we always do it together, because that’s the only way it will work. That’s the real deal, when everybody’s playing beyond themselves and what we’re playing is what’s being, in a sense, dictated to us. I believe music exists eternally, and in eternity, and when our group mind is in the right mode, we open ourselves to the possibility of being a pipeline for that eternal music. It comes down and it steers us. It just says “Okay. Now we’re gonna go over here.” And nobody, nobody in the band is controlling that. To me, that’s the highest art – to get to that point where you’re open to the eternal music. It’s not something you can control, either. You just have to let it happen.

This article originally appeared in the June/July 2002 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.