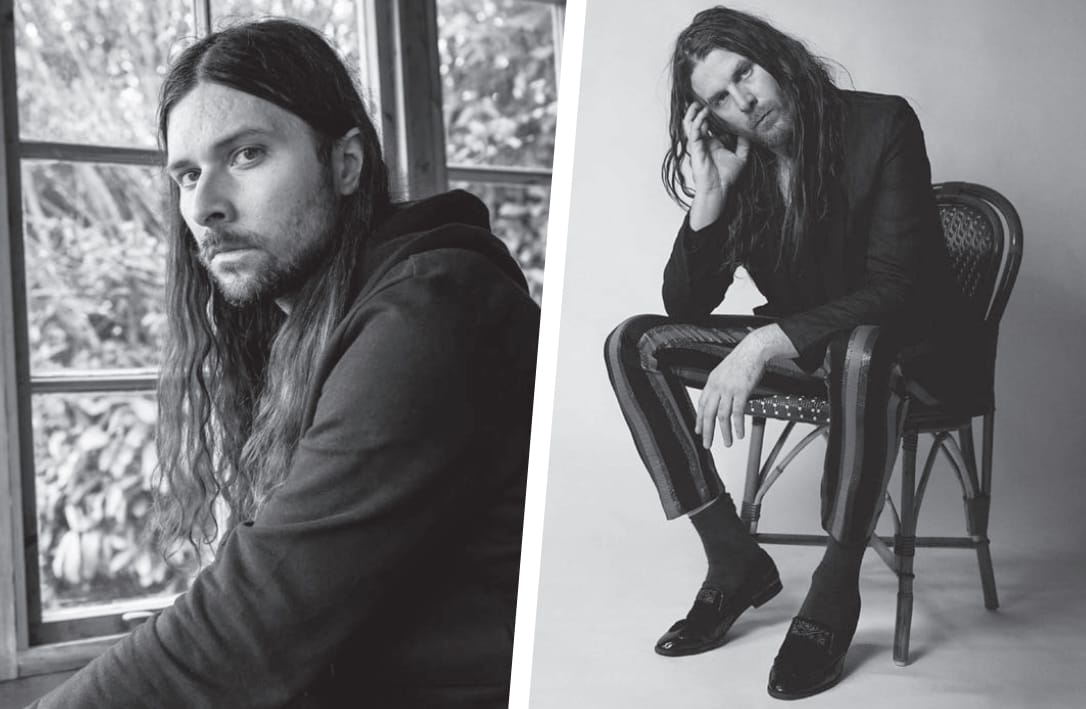

Jonathan Wilson and Mitch Rowland: Hollywood Vape

When Mitch Rowland moved from Ohio to Los Angeles in 2013, he didn’t luck out with the kind of music-industry Cinderella story you’d see in a made-for-TV movie. But he did arrive in the big city with a key creative inspiration: producer/songwriter and all-around local fixture, Jonathan Wilson.

“On the heels of moving to LA, I found [Wilson’s 2011 solo album] Gentle Spirit,” Rowland recalls. “That was pretty much all I listened to for a long time. It really grabbed me. What was so eye-opening about it was that I didn’t know you could sing that way to maintain a smallness about yourself as a singer. It was so refreshing to me, the way he approached his songs. He’s this extraordinary guitar player. While maybe his singing voice is small—at least on that record, it isn’t on others—the rest of the spectrum is so large. I still kinda look to him as a bit of a compass.”

Some major life events—including, for both, a pair of mind-bogglingly enormous side[1]man gigs—have occurred in the 12 years separating Gentle Spirit and Rowland’s debut solo LP, Come June. But listening to the latter, it’s striking how much of that original influence seems to have lingered: They feel like sibling albums, defined by some haunting, psychedelic, gently shifting folk. On the other hand, the ever-restless Wilson has somehow managed to expand that already-wide spectrum with his fifth LP, the kaleidoscopic opus Eat the Worm.

Besides their versatility, their mutual admiration, the pleasing symmetry of their names on the page (Doesn’t Wilson and Rowland sound like a Seals and Crofts-y ‘70s soft-rock duo?) and the fact that they both happen to be promoting crucial new records, these two guys do have a lot in common. They’re both multi-instrumentalists who can seriously rip on the guitar, both grew up in small towns (Rowland in Dublin, Ohio, northwest of Columbus; Wilson in the microscopic Spindale, N.C.) and are both probably best known for the music they make with others.

“It’s definitely birds of a feather,” Wilson says.

Since the late 2000s, Wilson has worked as a producer, engineer and session player at his own Fivestar Studio (formerly Canyonstereo), collaborating with artists like Dawes, Roy Harper, Conor Oberst, Angel Olsen and Father John Misty. (He also—no big deal—managed to join Roger Waters’ band, even playing on a recently rerecorded version of The Dark Side of the Moon.) Wilson enjoys having such a nonlinear résumé, being so tough to describe in a succinct sentence. That comes from essentially showing himself the ropes—and, throughout his career, always sniffing out the next interesting opportunity.

“With my whole studio technical background, I just had to do that,” he says, calling himself a “jack of all trades.” “Back when I was getting started, there was no one else around, so I had to figure that shit out too. I guess it all comes down to the ears that you have. If your ears are good, then what you do sounds good. But I do enjoy when people don’t really understand what I do. They scratch their head. It’s fun to be a mysterious person who does a lot of different shit.”

As for Rowland’s big connection— well, remember that Cinderella story mentioned earlier? His arrived via Harry Styles—the former heartthrob in boy band One Direction who morphed into a more organic, surprisingly colorful style character on self-titled 2017 debut. During the recording of that album, Rowland wasn’t expecting some kind of big break—he was employed as a dishwasher at a pizza parlor at the time. But his entire life changed when roommate Ryan Nasci, who was engineering a weeklong Styles session, floated Rowland’s name as a replacement for a no-show guitarist.

“I got T-boned by that opportunity—it came out of nowhere,” Rowland says. “I was breezing through the intersection, and pow! I wasn’t looking for it—how could one possibly look for that kind of situation? It will never happen again. That’s how random it was. It wasn’t supposed to go on for more than a week—or, for me, even a day. But in those days, Harry was looking for his team, and he found it, I suppose.”

Rowland became an integral part of that team: co-writing nine of 10 songs on the album, which topped the Billboard 200, and playing everything from guitar to drums and cowbell. He also stuck around as a member of Styles’ live band and, later, helped write multiple tracks on two follow-up records, 2019’s Fine Line and 2022’s Harry’s House.

***

Soon after Rowland arrived in LA, he and Wilson seemed to enter each other’s social and musical orbits—and a key mutual friend was producer Jeff Bhasker, who worked on the first two Styles LPs. But they both recall first meeting at an afterparty following Wilson’s 2018 show at The Fonda Theatre.

“We were making Harry’s second album in Malibu, and Jonathan’s album Rare Birds had just come out,” Rowland says. “I was like, ‘I don’t want to kill morale, but I’m going into Hollywood for this show. I don’t know about you guys.’ And everyone came. This person playing with Jonathan, [New Zealand folk singer Ny Oh], we wound up seeing her at the after party, and someone was like, ‘You should be in Harry Styles’ band.’ And she wound up [joining]. I guess I’m softly taking the credit for that one.”

Wilson playfully notes that they “kinda stole her,” clarifying that he’s “definitely happy” about how it all played out. “They’re our fucking homies,” he says, “so it’s a good thing.” Wilson even goes a step further, praising the Styles crew for how they approached what could have been a predictable, obvious pop project.

“That shit sounded great,” he says. “I was a part of that whole process—not on the album, but when they’d finish a song, they’d drive over to the house and I’d hear it in Jeff’s car. There was a bunch of shit like that—the whole thing was starting. There were some tunes that were nothing like pop songs—they were really fucking cool songs. It’s cool that it started from a real musical place. It wasn’t a pop think-tank kinda thing. I think it really speaks a lot about Harry. He had the smarts to go, ‘These are my dudes.’ Since then, Mitch has basically stuck around.”

Of course, Rowland wasn’t planning on being a sidekick to a chart-dominating, arena-packing pop star. Who could? But the time finally came to strike out on his own: “I always wanted to make my records. I wasn’t ready to do then what I’m doing now, so it all fell into place at the right time.”

He wound up showcasing more sides of his musicality—drawing on the open-tuned fingerpicking and hushed atmospherics of his guitar idols, traced all the way back to the meaty riffs of the Black Crowes’ Rich Robinson.

“When my obsession with Rich Robinson was [first] going on, I realized that he cites Nick Drake [as in influence]. After going through however many interviews and finding that out, that was my intro to Nick Drake—‘Who’s that?’ And from there, the one who resonates the most is Bert Jansch; that opened up a whole world. My survival kit as a guitar player and songwriter is full of open tunings.”

That openness is central to Come June, from the hypnotic “Medium Low” to the gently twangy “Here Comes the Comeback” (featuring Styles on backing vocals) and “See the Way You Roll,” a guitar piece he only fleshed out after the death of his grandfather. “I was stuck on the song when he passed, and then when he did, I was able to finish it,” he says. “That was kind of an unusual exercise in songwriting, I’d say.”

Sonically, the vibe was mostly intact from day one. “Only a few things really inspired this album I made—and Jonathan’s kind of an island in himself. But the three albums were the first two José González records and then [Bert Jansch’s 1971 LP] Rosemary Lane. I have to measure how much I love songs by if I’d have them played at my funeral. ‘Tell Me What Is True Love,’ the first song off of Rosemary Lane? Man, that’d make a hell of a funeral song. [These albums] are just vocals and guitar, very minimal, and I was drawn to that—not being in the pop production world for a second. I just wanted to do the opposite, and those guys do it so well. Those were logs on the fire for sure.”

Fittingly, there are parallels of influence between Come June and Wilson’s wilder and edgier Eat the Worm—namely, the desire to escape, at least temporarily, their other musical lives. Where Rowland was drawn to intimate folk, Wilson had an epiphany when discovering “Warm Rumours,” a Zappa-like 1972 oddity from singer[1]songwriter Jim Pembroke.

“I listen to [Captain] Beefheart and Frank every day, all the time,” Wilson says, detailing his taste for the weird and avant-garde. “But I didn’t know the Pembroke stuff until 2020 or something. I’d heard about Wigwam [the Finnish prog-rock band that once featured Pembroke as singer], but I didn’t know anything about them. When he passed away, I saw a video of him playing with Wigwam and was like, ‘Who is this guy? This is fucking great.’ It’s a songwriter—John Lennon vibes—sitting at a piano. He seemed like someone that I should known about. So I started to dig and explore, and that’s when I came upon ‘Warm Rumours,’ which was so inspiring. Those songs and the sentiment and what he’s doing with the weird characters and fucking voices and the talent[1]show vibe it has—it’s just weird. I had a moment where I was like, ‘That’s what I want to make—shit like this!’

“Doing the production thing, I get a little tired of normal song structures that everybody seems to show up with,” he continues. “That can be fun too, but it’s also like, ‘Really? Another song that goes from A-minor to C to G?’ It’s crazy. There’s some of that in there, too. But I have to explore with something that’s just different.”

***

With Eat The Worm, Wilson made his own version of a Pembroke-type experiment— chasing the noble goal of making music likely destined to be obscure, dwell in a used record bin and, hopefully inspire some other musician, decades later, to take artistic risks. The whole album is crammed with unusual aural collisions: the folk-rock fingerpicking, eerie vocal processing and jazz-pop orchestrations of “Ol’ Father Time;” the strings-meet[1]stoner-metal freak-out in “Hollywood Vape;” the springy jaw harp, clanging electronics, and enveloping orchestrations of “Bonamossa.”

“That’s one of those things where I was probably pretty fucking high at the moment, and I thought that was pretty cool,” he says with a laugh. “I put together that beat, and I have no idea where it came from. I made a combination of sounds, and then it sat on a hard drive for probably six months. That’s his personal writing-session vibe—you experiment and then it sits on the shelf. But I came back to that one and thought, ‘This is strange and fresh.’ I was trying to make an unheard combination of sounds.”

That goal, he says, defines some of the greatest music ever made. “Don’t forget that when they did the solo bit in [The Beach Boys’] ‘Good Vibrations’—or any of the amazing fucking Beatles overdubs that are [now] the gospel—people were probably like, ‘Holy shit, that’s way too weird.’ Those moments were bold. That’s what I’m after: ‘Don’t look back’ kinda shit. Own it—I try to do that shit.”

But Wilson’s musical ecosystem is vast, and each role—songwriter, producer, engineer, close-knit collaborator, sideman performer—seems to inform the others in some way. At the very least, wearing so many hats helps in the “shedding of ego, being in service to different songs and people, not getting high on your own supply all the time, thinking your shit doesn’t stink.

“I do not fucking envy my friends who are singular artists and all they get to do is their own shit,” he adds. “You get tired of hearing your own voice! There are times when I’ve been onstage playing a show of my own, singing my song—especially like a stripped-back acoustic solo show—and I’m not inspired because I’m doing this thing again. How do I stay inspired singing my own shit? But me being a true music junkie from a long time ago, I’m just excited to be involved in any way. I’ve done gigs on the fucking congas—whole shows—just to be up there with somebody. Or I’ll play the guitar or upright bass for people. I’ve done shit like that for years and years. I like to hide out in the cut.”

Maybe it all comes back to that jack-of-all-trades thing— either way, Rowland displays a similar lack of musical ego. Perhaps his biggest highlight from Come June was recruiting Ben Harper for a soulful lap-steel part on the wispy, mystic “All the Way Back Home.”

“That may have very well been [my favorite moment],” he says. “I became friends with Ben, and he’s been another inspiration since I was a teenager. I took an extra ticket off a friend and went to see him in 2006 in Columbus on the Both Sides of the Gun tour. It doesn’t happen too often, but it’s one of those moments where you see someone you don’t know and, the next day, you go out and buy every one of their albums. To have him on the record is a massive deal to me.

“What he did is just musicianship at the highest level,” he adds. “I didn’t know what he was going to do, but when I showed him the demo, we started talking about what we could do. When he came that day, he started stacking harmonies, which wasn’t the plan, but I was all for it. To be on the other side of the glass, saying, ‘Can you try that again?’ or ‘Maybe one more’—I didn’t plan on being in that position ever in my life. I didn’t want to fan-out too much. He’s kind of a master at underplaying.”

And as a final testament to their lack of ego, their overall curiosity—and, perhaps, the invisible glue that somehow binds them—Wilson and Rowland can’t seem to stop praising each other.

“I’ve heard [Come June] all the way through once, and it sounds great,” Wilson says. “I’m really fucking proud of him.” “At the moment, people are drawing comparisons [between me and] other artists,” Rowland says. “But even though Come June came out nothing like his music, [Wilson] is the one to blame the most for making me want to make my own record. Even on the Harry stuff as well—when I’m stuck in a rut, it was like, ‘What would he do in this scenario?’

“I’ve loved watching his music unfold over the last 10 years,” he adds. “Playing the Troubadour the other day was such a big deal because, almost 10 years ago to the day, I saw him playing there. I’m a super-fan for sure. The whole way through, he’s been such an important part of my life.