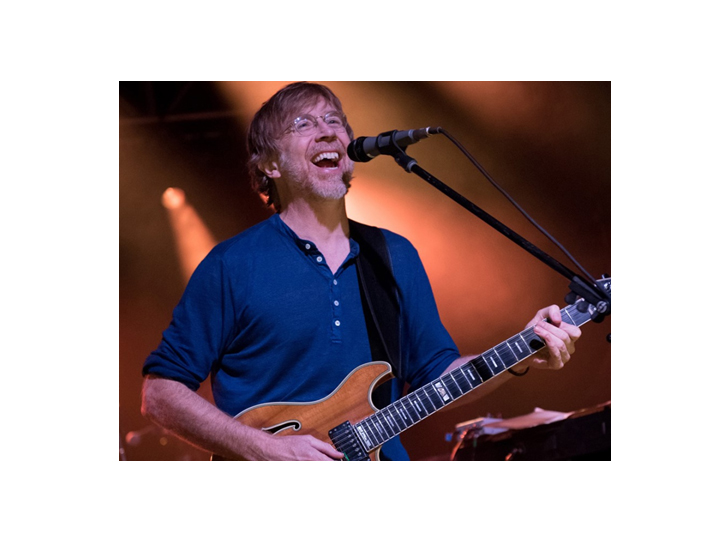

Trey Anastasio on the Power of Live

In this moment of social distancing and turmoil, many of us are yearning for the collective inspiration and joy that is unique to the concert experience. In a special Power of Live section that appears in our new issue, a number of singular voices chime in with their thoughts on the importance of in-person gatherings.

***

Before Trey Anastasio turns his thoughts to music, he acknowledges a stark reality— we’re in a deep moment of crisis.

“I’m here in New York and, for weeks now, there have been ambulances going by all day long,” he says. “I saw a documentary yesterday about the people in New York City tending to those who have lost their lives—the people who work in the morgues and the cemeteries and who get the bodies out of the buildings. There’s a whole infrastructure of people who do that every day. They’re doing it right now, every day.

“So it almost feels silly for me to be talking about how much I miss live music. I’ve experienced moments of confusion and even grief. But before those thoughts get to my mouth, my rational mind steps in and stops them because of all the profound problems that people are having. But live music is like spiritual food for me too, so I can relate to the people who miss it.”

Is there a particular moment that jumps to mind when you characterize live music as spiritual food?

The other day, someone click-baited me toward the Dec. 30 “Tweezer” from Madison Square Garden last year, and I watched it. I don’t watch a lot of live Phish, but I watched this. There was a very long jam and, somewhere around 13 or 14 minutes, it went into this quiet segment and, as I was watching this thing, I thought I physically saw the band members vanish. Phish has played in that room so many times. It was the night before New Year’s and it was just so comfortable and unified.

The thought that went through my mind, as I was watching it, was that whoever just went to the bathroom had as much of an effect on this jam as any of the musicians. It goes into this moment where Page [McConnell] is on the synthesizer and I’m strumming these chords and, almost in my mind’s eye, the band vanishes. The initial thought that went through my head was this: They say that if you went back to prehistoric times and stepped on a leaf and then went forward in time, then the whole universe would change. Well it occurred to me that the conscious thinking minds of everybody in this room, as individuals, had momentarily vanished. And whoever was in line for the bathroom or getting a beer was equally affecting the vibration of this jam.

No one’s leading or following—it’s this unified moment. Then, I thought of the backstage area where Ron Delsener always has this little party in his room. My dad will go there and friends of ours will stop by, and I was like, “Everyone is affecting the twists and turns of this jam.” And I mean everybody: Chris [Kuroda] running the lights, Garry [Brown] running the sound, the ushers, the guy at the beer stand, the people who like to stand in the back, the people who like to stand up at the top. In that sense, it’s the physical embodiment of what I consider to be spirituality, which is that we’re all connected. We are absolutely intertwined. I’m not a molecule floating freely around the universe. I’m part of a collective consciousness, like a ray of light from the sun.

Carlos Santana describes that moment onstage as collective intentionality, which draws in the bus drivers, the cooks, the security, everybody.

He hit the nail on the head. I was looking at that moment and I thought, “Everyone is part of it.” I was imagining, “Wow, Garry, just tuned a frequency in the kick drum and the whole room changed.” Then, I went further out and thought, “I know all these guys back there—all the security guards.” And I thought one of them just turned and talked to a friend and that everything was unified and it included everybody.

In my assessment, what’s so glorious about live concerts is that each of them is a unifying event that’s mysterious. You don’t know which way it’s going to turn. It’s improvisatory but everyone is also listening and reaching out and connecting. When you think about isolation as a concept— which has been the solution to fighting this disease—it really is contrary to the direction that we’re used to pointing the needle, which is togetherness. The analogy that we’ve talked about backstage so many times is that the venue is like a big, giant lifeboat and we want to pull everybody in.

That’s the magic of music. There was a period where one of my daughters was going through some hard moments in her life when she was a teenager, and one of the healing solutions presented to her was to join a drumming group of all teenage girls. I remember talking to some of these girls and they said, “When we start drumming, we can immediately tell which of the girls is having a bad day. We can feel it through the rhythm in the drumming more acutely than we can through talking.” I remember thinking, “Oh, my God. I can relate to that.” I can tell if Mike [Gordon] didn’t get a good night’s sleep when we start playing; I can tell if he didn’t drink enough water.

It’s all so open. You’re open to other people—breathing together and all that stuff. So this has been an interesting, unique moment where that valve has had to be turned off. That tube of connection with other people has been closed. Even with my family—and I know everyone is feeling this— we’re all separated. I go see my mom, but it’s masks and six feet apart, and everybody’s going through that. Grandparents can’t hug their grandkids. So it’s been an adjustment.

Looking back, can you recall a show you attended growing up that really opened your eyes to the connection between a musician and an audience?

I was just thinking of this. I recently liberated my car from the garage and went for a drive for the first time since March 13. I just filled the car with gas and put it back in my garage but that was enough. And when I got in the car, the windows were open and the original version of “Rosalita” came on. I suddenly remembered my first concert in 1978—Bruce Springsteen at Princeton University’s Jadwin Gym with about 3,000 people. I had to go with my sister because I was 14; I wasn’t allowed to go to a concert alone and she was a couple years older. He closed the show with “Rosalita,” and it all came back to me when I was driving in the car.

What a profound effect that concert had on me. I had a visceral memory of standing with my sister and looking up at the stage and it was just explosive. When they go, “Hey! Hey! Hey! Hey!” I remember, at one point, Bruce slid across the stage on his knees. And at the end of “Thunder Road,” he threw his guitar offstage and a roadie caught it. The whole thing was unbelievable.

I’ve met Bruce a number of times and, if I ever see him again, I have to remind him how much I owe him because that was my first concert and what I took away from it was that concerts are supposed to be explosive. This is how you do concerts: You blow the roof off the place every night. It was kind of the first thing I learned.

How has the quarantine impacted your creativity?

Before I can answer this, I’m reminded of those ambulances that keep driving past. I also think of the people who are out of work, which includes almost everyone I know—in almost every profession. I can’t ignore the fact that people are hurting; they’re feeling real pain.

Having said that, the world is unfolding and, because of the way it’s unfolding, I’ve been told that the way that I can help other people in my city is to stay home. So if I’m going to stay at home because I’ve been told to stay at home, then I’m going to do music at home. Luckily, I’ve been doing music at home my entire life.

That’s kind of the way I’m looking at it—“I’ve got to stay home so I’m gonna write music at home.” I’ve been writing music at home since I was in sixth grade; I’ve been jamming on glasses in the kitchen since middle school. So if kitchen jams are the way to go, then let’s have kitchen jams.

I’m trying to do what feels natural to me right now—not doing a livestream or a Zoom call, but doing what I’ve done since high school. I get up, go in and write. I did that before there was a Phish. I’d be in the basement with a keyboard and an amp writing “Run Like an Antelope” and “Slave to the Traffic Light.” All that stuff was done before there even was a Phish. Sometimes friends like Tom [Marshall] would stop by, but 90 percent of it was done alone. I’d spend hours every day with a four-track machine and I was in heaven. “The Wedge,” “Bouncing Around the Room”—all those songs were written that way. Every single one of them started off as a four-track demo that I did mostly alone.

So far, there’s 14 new songs. Tom has sometimes been writing lyrics, but I’ve been writing them as well. I’m doing this the same way that I always have. I’m sleeping in my own bed and hanging out with [my wife] Sue and not racing out of a hotel. I can’t wait for live music to come back, but this is where we are today. This is reality and I’m not going to swim upstream.

Ever since I was a very young child, I have felt music flowing out of me. So if people honor me with their attention, then I feel like that’s the function that I was put on Earth to do. And I feel like having found that function, I’m blessed. So whatever situation life gives me, I will wake up in the morning, hear music and try to translate it.

When I look at music history, I see musicians who have lived that. One example is Sun Ra. His group lived together in that place in Philadelphia. We were lucky to see him many times. I remember Fish and I went to a show in Boston at this little club where there were more people onstage than there were in the audience. And Sun Ra had this thing where he’d say, “I’m like a bird. I get up in the morning and I just make sounds.” He made hundreds of records. He had a lathe and he pressed his own records from his house. That, to me, is sort of the highest level, which is—however the world turns politically and socially—you get up in the morning and thank God that you can make music that day, wherever you are.

Another example would be Stravinsky, possibly my favorite composer. One of my favorite pieces is his “L’Histoire du soldat (The Soldier’s Tale).” It premiered in September of 1918 which, by the way, happened to be during the Spanish flu pandemic. According to my mentor [Ernie Stires]—who taught me composition—it was right after World War I and all the musicians from the orchestras had been drafted and there was a pandemic. Here’s this guy, who’s the greatest composer on Earth at the time, and there’s no orchestras. So Stravinsky had to write that piece for a septet because those were the limits that were forced on him, and he wrote one of the most incredible pieces of music ever.

This goes back to the fact that I don’t control the universe—all I can do is adjust my perspective. So as a musician, if life gives you a pandemic and all you’ve got is a synthesizer, a guitar and one microphone, then make music with that.

There are moments when I watch something like the video montage of the funerals in New York City and start thinking, “What am I doing? I should do something.” What’s going on is just so messed up and the one thing I have to offer is music. I don’t have anything else to offer. Then again, the one thing I can offer is music. So I’ll write some songs, put them out and hopefully people will get some joy out of it—some comfort or a little distraction.

You mentioned that you’re not doing livestreams or performing via Zoom. Jason Isbell recently appeared at Brooklyn Bowl Nashville, with fans tuning in and having their own feeds projected over the bowling lanes. Have you considered doing something like that?

I’ve been asked numerous times to do similar things to what Jason did. I love Jason and I’m friends with him. It was a great thing. But for me, so far, I’ve said no.

So much of what I do is informed by the close proximity of the people in the front row—in the front 10 rows—and even by the person in the back row. We don’t have a song list because that connection is a big part of who we are as a band and who I am.

I think the Phish experience is very much about the “group think.” It’s the same with TAB or the trio. I do a prayer before I go onstage. I don’t decide what the first song’s going to be. I think about it a little, but I can’t decide until people are standing in front of me. I’ve tried. The guys in TAB make fun of me. They’ll ask, “What are we going to open with?” and I’ll tell them, “We’re opening with ‘Sand.’” But then after I walk on the stage and I see everyone, I turn around and say, “We’re not opening with ‘Sand.’”

I don’t know if I want to play without our community with me. It’s a bridge I haven’t been able to cross.

I have been asked by many people: “Let’s do this Zoom concert” or “Let’s do it Brady Bunch style.” Maybe it’s my spiritual belief system, but I feel like this is where we are today and this is where I am— “I’m home. The concert isn’t happening right now.”

I almost don’t want to go halfway. If it’s possible, I want to celebrate that resurgence of live music with our family, which is our audience. And it doesn’t even feel like an audience—it feels to me, like a community.

I’d like to connect with that community, but I’ve found a way to do it because I’ve put out those 14 songs from my bedroom. I like being in contact but I might just wait [for a show]. I’m trying to follow my heart through this.

I’ll tell you another thing: We had to stop Phish once before. We went many years and then we paused and the pause was from 2004 through 2008, while I was a getting my health together. Then, we did end up making an album and maybe that’s something we’ll do. I don’t know. But we didn’t do any shows and we didn’t do any kind of half-shows. We waited.

Then, we came back to Hampton Coliseum in 2009 and our community was there. Not everyone was there but it was a large group of people. I’ll never forget that moment as long as I live, which was the opening song in Hampton when everybody was back. When I think of that moment, it can make me cry.

So that was five years. I really hope we don’t have to wait another five years. But I would prefer to gather with everyone. I want to gather with Page and Mike and Fish and everyone, if it’s possible.

I’ll admit, I have thought it might be fun to do a drive-in show with the trio, but I’m not even going to do that. I want to see people’s faces. Again, I adore Jason. But this is what feels right for me. I need to listen to people in the room. It’s what I do.

The virus is going to have its way. So again that goes back around to: “Yes, I want live concerts to come back, but I’m not going to race into something half-baked just out of my desire for things to change.”

What’s going on is complicated and tricky. I’m just speaking for myself, but what I try to do is wake up with gratitude—“I’ve got music, I’ve got rhythm. Who could ask for anything more?” And then get to work writing songs and putting them out.

I can’t think about all the stuff that’s gone because it’s too much to even think about. So the way I’m trying to respond to the moment is by writing songs until they let me play again. But when I do play live, I’d really like our community to be there with me, if there’s any possible way.

J20: Dean Budnick