The Meters: Funk Pioneers (Relix Revisited)

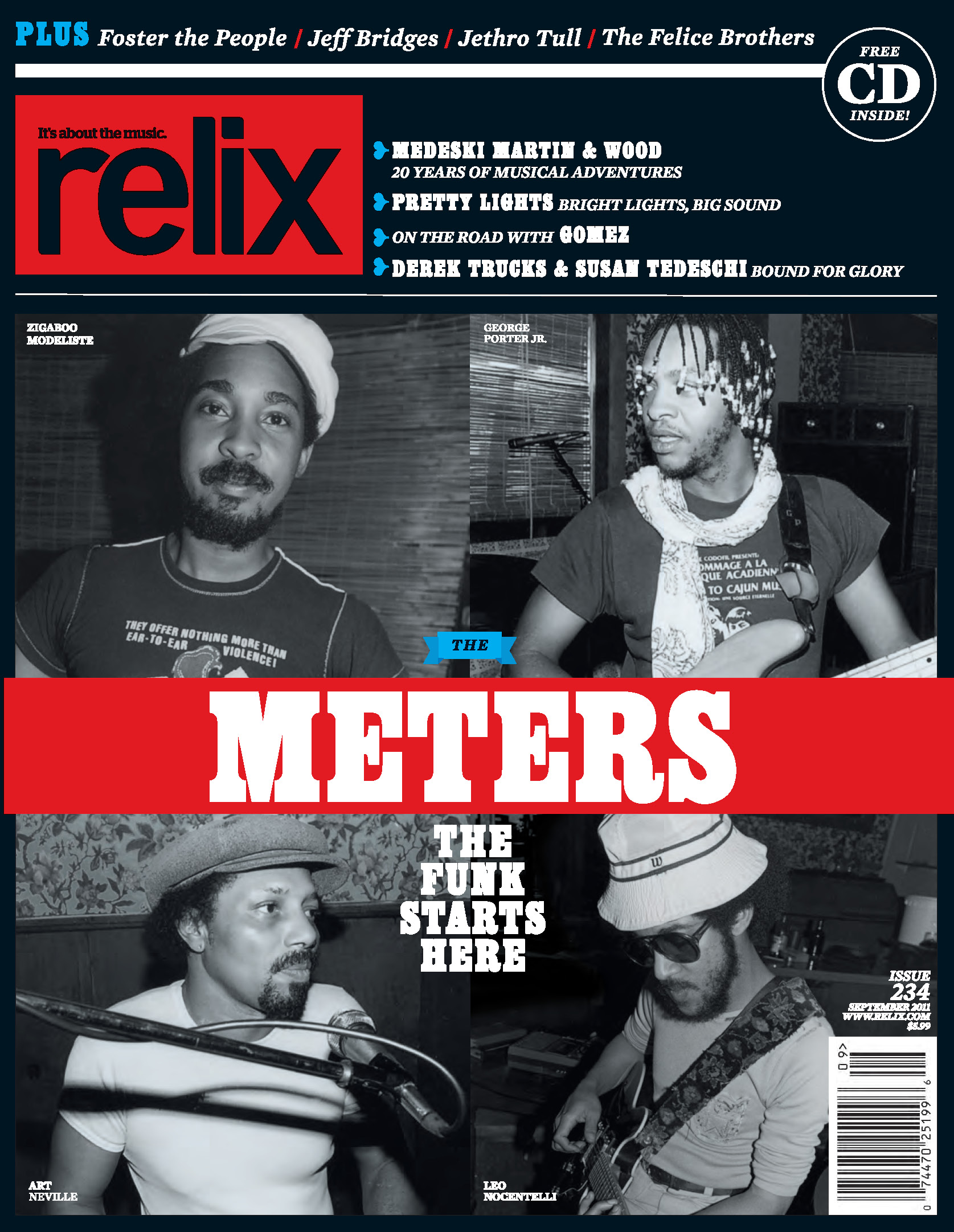

In the wake of Art Neville’s passing, we’re looking back on our September 2011 cover story, showcasing the lasting legacy of The Meters.

1969 was a fulcrum year in human history. Man walked on the moon. A generation found its voice at Woodstock (and in England at the Isle of Wight), only to echo its darker side at Altamont. The Beatles bid farewell with a concert on the roof of Apple Records before releasing the culmination of their collective genius, Let It Be. Even Hollywood reflected the change in such soul searching films as Midnight Cowboy, The Graduate and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. In Sports, the New York Jets won the Super Bowl as rank underdogs and the hapless Mets won the World Series.

Black pride asserted itself on the charts as Billboard changed the title of its Rhythm & Blues category to Soul. Meanwhile, people on the streets were calling it funk. The headliners of this last transition included two heroes of Woodstock–Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix–and the Godfather of Soul, James Brown.

But a virtually anonymous instrumental band fresh from the clubs of New Orleans changed the music just as profoundly–The Meters.

The story begins, as so many New Orleans stories do, with a musical family. Art Neville, the oldest of six children, was born in 1937. Through his father Art senior and mother Amelia were not musicians (Amelia was a dancer), they were avid listeners and encouraged their children to play instruments. Art became lead singer and keyboardist of The Hawketts, who recorded “Mardi Gras Mambo” in 1954. (The song has since become a standard during Carnival time in New Orleans and has made Neville a local celebrity.)

Shortly after, Neville asked young local guitarist Leo Nocentelli to play with the Hawketts, putting the first piece of what would become The Meters into place. “I was maybe 16 years old when they recorded ‘Mardi Gras Indian,’” says Nocentelli. “Art hired me into the band. For me, that was like getting invited to play with The Beatles.”

Nocentelli had already drawn attention to himself as a whiz kid guitarist for local producer Allen Toussaint.

“Allen had a tremendous effect on me,” says Nocentelli, who Toussaint employed on such Lee Dorsey hits as “Ya Ya,” “Workin’ in a Coal Mine,” “Ride Your Pony” and “Get Out My Life Woman.” “Lee Dorsey was a good friend of mine. He used to fix my car. He was a better body and fender man than he was a singer. He used to make money singing but his passion was working on cars.”

Action around the Neville home on Valence Street in the 13th Ward was inspiring to local kids, including a new arrival on the block—Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste—who befriended Art’s youngest brother, Cyril.

“They lived across the street, a couple of houses down,” recalls Modeliste of the Nevilles. “I was 1133. They were 1108. Art and Aaron Neville were working with the Hawketts. Me and Cyril were going to school and playing football together. Cyril’s brothers and them used to rehearse in the front room of the house. I would sit outside and listen to them play. And that’s when my interest really started peakin’ and I knew I wanted to play the drums.”

George Porter, who also lived in the neighborhood, which he jokingly calls “Nevilleland,” began his career in music as a guitarist.

“I didn’t make a good impression on Art at all,” says Porter, who was introduced to the keyboardist by guitarist Herbert Wayne. “I was a rhythm guitar player and he needed a lead guitar player. He wasn’t soloing all that well and neither was I. This was at a bowling alley out in Gentilly [La.]. Art told me I was a lousy guitar player and he would never be calling me again.”

Porter switched to bass during a brief stint with the soul/blues singer Irma Thomas before joining guitarist/singer Irving Bannister’s group. This time, Art liked what he heard.

“George had three strings on the bass when I first saw him play bass,” says Art. “And he was doing some serious playing with those three strings. So I asked him to join my band.”

Meanwhile, the future drummer of The Meters was hanging out in the front of his house, listening to Art’s band and jamming with Cyril and their friends. “I knew him but I didn’t know he could play,” Art says of Zig. “When I finally heard him play, I knew he was a special drummer.”

We both wanted to be drummers,” says Cyril. “Me and Zig were kind of apprentice drummers for Art’s band.”

Art enjoyed being a mentor to Cyril and encouraged him to take part in the music making, too.

Cyril remembers the musicians who came to the house accepting him.

“There was never a time when an older musician didn’t want us around,” Cyril says. “They always wanted to teach us how to play music.”

Among the shows and places Art took his younger brother was the T.A.M.I. Show, the legendary concert captured on film in which James Brown blows away The Rolling Stones with an electrifying live performance.

“Man, I’ve still got scars on my knees from doing the James Brown, doing splits in the street when we got out of there,” Cyril laughs.

“Me and Cyril aspired to be drummers, but our whole thing was being dancers,” adds Modeliste. “We were better dancers than anybody in our neighborhood. I mean nobody could touch us when it came to dancing.”

Modeliste started playing drums professionally when he was barley a teenager. His biggest influences were Buddy Williams and Smokey Johnson, both drummers who Art occasionally gigged with.

“Smokey was a guy that had so many different things going on,” says Modeliste. “He could play straight ahead jazz with the greatest of ease, but when it became funk—what they were calling funk at that time—he played the backbeat and all that kind of stuff. He made me think about the importance of the drummer. The drummer sets the tone and he had a way of working the hi-hat cymbal, which is where I got the idea to use the hi-hat instead of the crash cymbal all the time.”

The up-and-coming drummer worked in another 13th Ward neighbor’s band, Deacon John, where he continued polishing his skills. He then got the break he was looking for: Art asked him to join a band for a gig at the Nite Cap Lounge.

“Gary Brown was on tenor sax,” Modeliste recalls. “They were getting a nice crowd on the weekend. So I went with Art, at first as a sub, then the drummer he was working with didn’t wanna play no more. He became an ordained minister.”

Art had the lineup he wanted. “I never remember anyone else from that band except Ziggy,” he says.

A local DJ christened the group “The Neville Sound.” When Art got a chance to move down to Bourbon Street to play at the Ivanhoe, Gary Brown dropped out, thus creating the quartet that would eventually be known as The Meters.

It was still the Art Neville band, playing covers and jazz tunes and hip instrumentals. While the group was gradually developing its own sound during its Ivanhoe residency, producer Allen Toussaint would sit in his car with the window down outside of the club and listen. Toussaint knew Modeliste from using him as a session man and Neville from

some sides that he recorded as a leader of the R&B group Specialty, but he heard something else, too. He heard the future.

“Me and Cyril aspired to be drummers, but our whole thing was being dancers. We were better dancers than anybody in the neighborhood.”

-Zigaboo Modeliste

Two tracks by The Meters on their eponymous 1969 debut—“Sophisticated Cissy” and “Cissy Strut”—became R&B hits. “Cissy Strut” even crossed over to the Top 40. The tracks were inspired, to a degree, by the precision of the Stax/Volt session band Booker T and the MGs, but because the musicians were from New Orleans, they brought a unique, swinging groove to the pocket—syncopated polyrhythms inherited from the deep African musical roots at the heart of the city’s music.

People have notated this music on paper but a technical description cannot explain the internal communication among the four members of the band as they dance in place, playing as if they are all part of one huge percussion instrument.

Modeliste’s drums are the heart of this entity as all four of his limbs work independently in quick, precise cross rhythms that click and sizzle while Neville plays sudden stabs of color on the Hammond B3 organ in between the beats, finding spaces that don’t seem to exist. Meanwhile, Nocentelli plays the melody in terse, dry, single notes that skip across the arrangement like flat stones bouncing off the surface of a pond. And Porter, who is not content to play I-IV-V, doubles the melody line, creating an entirely new sound.

Listeners marveled at the completely revolutionary sound of these recordings. Many young guitarists became frustrated trying to figure out how to replicate what they thought were two guitarists playing at the same time, but the secret to The Meters’ sound was the way that Nocentelli and Porter played together.

“Of course this had been done in jazz—the bass playing the melody part—but it hadn’t been done in R&B up to that point,” explains Nocentelli. “’Cissy Strut’ was one of those songs that defied convention and I’m just happy that people liked it. We didn’t overdub anything back then. It was all recorded live.”

“Cissy Strut” immediately became the definition of funk. At around this same time, James Brown’s sound evolved from the R&B of The Famous Flames to the heavy groove and funk of the J.B.’s “It influenced a lot of people,” says Nocentelli.

It also influenced Led Zeppelin, who asked the band to perform at a private party for them. “The gig was at a warehouse and we were all excited,” retells Nocentelli. “We got all dressed up and we set up in the corner. I’m looking around and saying, ‘There’s nobody in here. No guests, no nothin’. So these three guys walk in—Jimmy Page, Robert Plant and I think the bassist, John Paul Jones. Well, we decided to play anyway. So the whole thing was designed for us to play for these three guys. With all due respect to Led Zeppelin, there are a few things I can hear in a lot of their songs that they got from us—especially the syncopation between the bass and guitar.”

The Meters also exercised a subtle and profound effect on Bob Marley, who began recording with the Wailers using some of the same techniques that they pioneered.

“All you have to do is listen to ‘Lively Up Yourself,’” Nocentelli points out. “You can hear the syncopation between the bass and the guitar line. It sounds like The Meters.”

The Meters became one of the most influential bands of their era, evolving into the ‘70s to transcend the instrumental realm and become full fledged funk ambassadors on their own recordings and the go-to studio band of the era.

Singer Robert Palmer launched his career with The Meters pushing him along on Sneaking Sally through the Alley (1974). Dr. John scored the biggest hit of his storied run with the Meters backing him on In the Right Place (1973), then went on to make the overlooked gen Desitively Bonnaroo (1974) with the band. The Meters also helped launch Labelle with the unforgettable “Lady Marmelade” (1974).

Dozens of other artists from Paul McCartney to Paul Simon searched out The Meters to help them add some funk to their sound. The Meters were also the band behind one of the greatest Mardi Gras Indian recordings ever made, The Wild Tchoupitoulas (1976).

The Meters went on extensive tours, playing the Chitlin Circuit in the South and theaters like The Apollo in New York. George Porter says that what they were doing could be described in jamband terms.

“The original Meters were a jamband,” he argues. “The Meters were absolutely a jamband. While we recorded those first three albums, we got sent on the road immediately to play four-hour gigs. We only had 38 minutes of music at the beginning. Back in those days, we played almost every song that was on the record. We stretched everyone of the songs out.”

In 1971, the record company that had been releasing The Meters’ music went out of business. It was clear that the era of the instrumental version of the group was also over. After recording Cabbage Alley (1972), a solid but commercially disastrous first album for their new record label Warner Bros., Art convinced the band that they needed a frontman [written this way here, and then as two words later].Cyril Neville joined the group for what may be their finest album, Rejuvenation.

“With all due respect to Led Zeppelin, there are a few things I can hear in a lot of their songs that they got from us—especially the syncopation between the bass and the guitar.”

-Leo Nocentelli

“We only had Art Neville as a singer at the beginning,” says Porter. “When Cyril got into the band on the Rejuvenation record, the focus became a vocal group, which I thought was good. Cyril was a screamer kind of guy and Art was a balladeer.”

Nocentelli says that Rejuvenation is his favorite Meters album.

“A lot of my heart and my soul went into that record,” he says. “I spent a lot of time writing that stuff with the help of Zig. For a lot of the early instrumentals, I would come up with the stuff in my back room, but starting with Cabbage Alley, Zig and I got close and started appreciating each other’s talents as far as writing. I would come up with a lot of the riffs, like on ‘Just Kissed My Baby,’ ‘People Say,’ ‘Africa,’ ‘Jungle Man.’ I would come up with the music and some lyrics but Zig was—is—a very clever lyricist. Rejuvenation is where the marriage between Zig and I really happened.”

Just after the next album, Fire on the Bayou (1975), came out, The Meters were preparing to go on the first of two tours with The Rolling Stones.

“Cyril was very important to us then,” says Art. “We needed a frontman, especially opening for The Rolling Stones.… [The Stones] would never let us start until they got to the place we were playing and they all came backstage, right behind the stage, watching what we were doing….I remember somewhere one night, the crowd sat there and just looked at us. Mick Jagger came out and said, ‘You know who this is? You know what’s going on? This is the real thing. I wanna hear somebody making some noise.’ Then the whole audience attitude changed. Those guys were so nice, man. Best guys I ever worked with.”

Little Feat leader Lowell George, who had first gotten to know The Meters while recording tracks with the band for Robert Palmer’s record, became a quick fan, too.

“I think he was also on ‘Just Kissed My Baby’ and ‘Jungle Man,’” recalls Porter. “I know Lowell was a big fan. A couple of times, when we were doing the Stones tour, Lowell would disappear off the Little Feat tour and come hang out with us for a couple of days. His manager called our manager and said ‘Man, is Lowell George there?’ He said ‘Yeah, he’s hanging out with Leo.’”

Even as The Meters appeared to be having their breakthrough on the Stones tour, the band’s business affairs were plummeting. Marshall Sehorn—a rather flinty character who, along with Toussaint, had managed the band and oversaw its publishing rights since the mid-‘60s—released an unapproved album of demos and partially-completed songs called Trick Bag (1976). Adding insult to injury, Sehorn committed The Meters to The Wild Tchoupitoulas Mardi Gras Indian album in a deal which left him with the lion’s share of the money.

The Wild Tchoupitoulas record, which featured all four Neville Brothers and The Meters, is considered to be one of the most important cultural documents of its era. According to the key post-WWII New Orleans history, Up from the Cradle of Jazz, lead Indian George Landry (Big Chief Jolly) said he wouldn’t record a second Wild Tchoupitoulas album because “he had not been properly compensated by Toussaint and Sehorn.”

There was a final act in the story of the original Meters: an album produced by David Rubinson that eventually came out as New Directions (1977), the band’s final release. Compared to previous efforts, the record sounds pretty good considering that the atmosphere in the studio was so negative that Rubinson shut down the session at one point, telling the band to get back to him when they sorted out their disagreements.

The Meters knew that a great opportunity had foundered.

“By the time we finished that album, the relationship between Warner Brothers and The Meters had dissolved,” says Modeliste. “It was just a bad, bad contract. Finally, when the contract ended and the group was free, that was it. As soon as the contract expired, I tore mine up. This guy wanted to sign us to another long contract. I said, ‘Why would I wanna do that?’ They had just opened the door and let me out. Why would I want to walk back into that?”

For all their greatness, this band was never able to build their own success. In 1977, The Meters officially parted ways.

One of the ongoing motifs in the musical recovery of New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina is the Meters’ influence on the city’s distinctive sound. Countless bands perform a version of “Cissy Strut,” which has become a kind of Rosetta Stone for translating funk across themes and genres. The Radiators, who just called it quits after a 33-year run, probably played more Meters covers than any other group—besides those affiliated with The Meters themselves. The Rads also cut a tribute song to The Meters, “Metric Man,” written by the band’s guitarist Dave Malone.

“When we were coming up, we could still go see The Meters,” says Malone. “It was the way they put the songs together that was so amazing. Every piece of the puzzle was perfect. Leo played what seems like really simple stuff on these songs, but they were perfect guitar parts. When people asked us what our influences were, we always said The Meters. It was more about the way they put the songs together than how they sounded. The music sounds simple until you actually try to play it.”

Fans were excited when the band announced a reunion show just three years after the split. Yet, this 1980 gig, which led to a disastrous film deal, left the members with such hard feelings that another reunion—even one under the best circumstances—seemed unlikely.

For all of the business problems that The Meters faced—and there were many—the music only grew in stature as years passed. Art Neville and his siblings Charles, Aaron and Cyril went on to fame as the Neville Brothers, using Meters material as the foundation of their sound.

Porter, Modeliste and Nocentelli all formed their own groups. Eventually, Art Neville and Porter formed an offshoot band, the funky Meters, playing Meters songs with a new drummer and guitarist. But the demand for the original quartet never waned.

In 2000, the four original Meters played a legendary stand in San Francisco, and the group has reunited every few years since then. In 2005, The Meters demonstrated their ineffable magic to a new generation of listeners with a mind-bending set before tens of thousands of people at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. Any momentum that this show built for a more permanent reunion was destroyed by the devastation of Hurricane Katrina and the federal flood that followed, an inundation that took a stiff toll on both Neville and Porter. “Oh, man,” says Art. “It was serious. Scattered us all over the place.” Since Katrina, Art has seen a lot of his peers pass away, but he doesn’t dwell on the losses. “I’m the only one that’s not going anywhere,” he chuckles. “I feel pretty good. I’m up and I’m around—I move around a little bit. I can’t explain it, but I feel better when I play music. Ever since my back operation I’ve slowed a little bit, but the music picks me up.”

Earlier this year, when the original Meters announced that they would join their producer Allen Toussaint and Dr. John to re-create the Desitively Bonnaroo album at the tenth Bonnaroo festival, Meters fever spiked once more. Members of Galactic even canceled a show in order to be on hand to watch the event themselves.

“I was surprised by the offer to play the Desitively Bonnaroo album,” says Porter. “When I heard the rumor that was it was gonna happen I said, ‘Yeah, right. Tell me about it when you get the contract.’ I had been in too much monkey business with The Meters.”

The deal went through rather quickly, though, and before the band even played a note, the Bonnaroo festival promoters had booked them to play their west coast festival, Outside Lands.

“The [Bonnaroo] show was great,” relays Porter enthusiastically. “What I liked about it was all the egos got checked at the front gate. Everybody walked into the room intending to cooperate and do their absolute best to make this all work. Everybody knew that this was not gonna be a walk in the park because the music—from my perspective—was one of the most complicated things we’d ever done.”

Desitively Bonnaroo, according to Porter, was particularly challenging to perform live because of all the various parts each song had—“it wasn’t just a pocket groove thing.” Once the band had assessed what they had to do in terms of arrangements and direction, they decided to bring in Toussaint (who had originally produced the record) to act as bandleader in charting horn and vocal arrangements. Even then, it was a challenge.

“I listened to the record two or three times a day for two months before I started playing it,” says the bassist. “It gave me a renewed appreciation of the record.”

It also gave him a new appreciation of The Meters.

“The Meters were meant for more, but the problem I always had was that the band just never saw it,” concludes Porter. “The band never knew its real place—never knew how good it was. The Meters didn’t know that they had more to offer than being just like everybody else.”

“The Meters were meant for more, but the problem I always had was that the band just never saw it.”-George Porter

Not even Art Neville is sure what enduring quality defines the band.

“The music is funky—that’s all I’ve been able to come up with,” he says. “The young folks seem to be moving toward what we’re doing. Every time we play ‘Cissy Strut,’ the crowd breaks into chaos.”

So is there a future for the original Meters this time around? Nocentelli says that his dream is to make a new album with the band, but Porter and Modeliste are skeptical.

Art Neville—who believes that the record is going to happen and is hopeful of a more permanent reunion—says that he and the other members are already writing new material.

“We try to live up to everything that we did,” says Art in reference to what fuels the band’s current creative process. “Hopefully this roll that’s coming around right now with the reunion is something we can build on. Then, everybody will know our legacy. They’ll know that we did something to help the rock and roll.”