Young and the Restless: Neil Young on Promise of the Real, Paul McCartney and Telling an Earth Story

This excerpt originally appears in the January_February issue of Relix. To subscribe and read the rest of the cover story featuring Neil Young, click here.

A few years ago, the TransCanada Corporation proposed a section of the Keystone XL Pipeline that was slated to cross the Ponca Tribe’s “Trail of Tears.” Neil Young didn’t like that one bit, so he took action the only way he knows how to when a cause moves him to join the front line—he put together an all-star concert with some of his famous friends.

The benefit show, dubbed “Harvest of Hope,” took place in late September 2014 on the Tanderup family’s farm along the route near Neligh, Neb., featuring co-organizer Willie Nelson, his twentysomething sons Lukas and Micah and a number of area musicians. Young was about to launch into a round of solo dates at the time, so he asked Willie’s sons and the members of Lukas’ band Promise of the Real to back him for the second portion of his set. The collaboration clicked, and Young walked away from the benefit with both a new group and enough political ammunition to help convince President Obama to veto the proposed section of the pipeline a few months later.

“They’re an amazing band, and they have a great groove,” Young says of Promise of the Real, who have grown into his closest musical allies, two years and a flurry of new albums later. “So, when we play together, we can improvise and jam, and they all sing great. They all sing more on pitch than I do. It was about stopping the Keystone [XL Pipeline] from going through a farmer’s land. Everybody was there so I said, ‘I’ll show you a couple songs I want to do,’ and we did ‘em. ‘Who’s Gonna Stand Up?’ was one of the first things we learned.”

Young had already tested the waters two weeks earlier in Raleigh, N.C., during Farm Aid—the charitable show he regularly hosts with the Nelson family—inviting Lukas and Micah to sit in for his final selection of the night, “Rockin’ in the Free World.” He had recently wrapped-up a European tour alongside his fierce, improv-heavy, garage-rock group Crazy Horse, with whom he had been exploring some new material, including the eco-conscious protest anthem “Who’s Gonna Stand Up?”

It was perfect timing: Despite Lukas’ family lineage, Promise of the Real have always been more of a jamband than a country outfit or ven an Americana act and, less than a month later, Young asked them to back him during his other annual event, the Bridge School Benefit Concert. Micah—who has his own psych-punk-orchestra, Insects vs. Robots—signed on as something of an “in-residence” auxiliary member of the ensemble. Young hasn’t looked back since.

“They’re very supportive, and they’re a working unit— nothing’s in their way,” Young says while calling from his Los Angeles home in December. “They love my music, and they actually come to me with suggestions all the time with songs they’d like to do. And I know that whatever song I want to do, they can learn how to play it as soon as I show it to them. So it’s given me between fi e and eight times more songs to play than I’ve ever had before in my life. That makes it a lot of fun and that’s why I keep doing it—because I’m having a good time.”

Though Young is famously one of rock’s most restless spirits, during the past few years, he’s jumped between projects at an even more fervent pace than usual. In 2010, he reunited with Buffalo Springfield for the first time since 1968 for a Bridge School appearance and stuck with the legendary group for a handful of dates in 2011, before putting that not-in-this-lifetime tour to bed so that he could revive another long-dormant ensemble, Crazy Horse.

He spent much of the next three years on the road and in the studio with Crazy Horse, but not without some bumps in the road. First, the quartet cancelled a few dates in 2013, including a headlining appearance at the inaugural Lockn’ Festival, when guitarist Frank “Poncho” Sampedro broke his hand and, the following year, Rick Rosas subbed for bassist Billy Talbot after he suffered a stroke. In addition to solo dates that recalled Young’s early work under his own name, he even found time for a one-off CSNY reunion at Bridge School in 2013.

Young has also entered into one of the most prolific periods of his recording career, releasing six proper albums in the past five years in a variety of configurations, as well as a slew of live and archival offering . On the studio front, he partnered with Crazy Horse for a set of repurposed traditional numbers and children’s ditties, Americana, and for the equally hard-rocking Psychedelic Pill in 2012. Then there was both the unexpected set of singer-songwriter covers A Letter Home—recorded at Jack White’s Third Man Records— and the swinging big-band set Storytone in 2014, as well as a collection of originals captured at a converted movie house with Promise of the Real, The Monsanto Years. More recently, in December 2016, he dropped a stripped-down album, Peace Trail, and he’s already back in the studio working with Micah, Lukas and his band.

Though Young laid down Peace Trail with noted session drummer Jim Keltner and bassist Paul Bushnell, Promise of the Real’s spirit guided the sessions. In fact, Young first heard about Bushnell through Micah, who nabbed the bassist for his upcoming album.

Though Young laid down Peace Trail with noted session drummer Jim Keltner and bassist Paul Bushnell, Promise of the Real’s spirit guided the sessions. In fact, Young first heard about Bushnell through Micah, who nabbed the bassist for his upcoming album.

“I have been playing with Promise of the Real and I still am playing with them, but they weren’t available,” Young says of their absence from the record, though they’ve toyed with some Peace Trail songs live. “They were on the road and the songs just came to me and I wanted to record them, so I called up Jimmy. We’re good, old buddies and we understand how to do it together and have a great time, so I just went for that and we did this record.”

Young recorded Peace Trail in only four days at Rick Rubin’s Shangri-La Studios, and most of the 10 tracks are first or second takes. He produced the album—his 37th— with longtime collaborator John Hanlon, and the swift rollout allowed Young to address some of the day’s pressing issues. In particular, numbers like “Indian Givers” rally in support of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, whose land is currently being threatened by the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“Some of these songs are about things that are going on right now,” he says. “The First Nations people and the corporations are going at it head to head, and it’s a historic moment. It’ll probably continue up there all winter long and get bigger and bigger.”

He pauses to address how the situation has changed as more musicians and volunteers have lent their voices. “The situation is bigger than it was when I wrote [these songs],” Young says. “This thing is growing, and it’s an awareness of a situation that we face in this country and other countries like it so it strikes a chord with everyone. Corporations are controlling our government— and that’s what’s going on. Now, we have them head to head. Someone says, ‘You can’t do this,’ and the corporation says, ‘We’re doing it anyway.’”

Other parts of the largely acoustic Peace Trail are more closely related to Young’s own life. “Can’t Stop Working” feels like a direct statement on his reluctance to slow down, despite pushing past age 71, and “My New Robot” is perhaps the first relationship song to feature a cameo by Amazon Echo’s voice-activated assistant Alexa.

Young has devoted a lot of time and energy in recent years to launching Pono— a music download service and dedicated music player focusing on high-quality recorded audio. The autotune-colored “My Pledge” is a meditation on how people listen to music in the modern era that name-checks both the Mayflower and Jimi Hendrix. (Young, who recently revealed that he even met with Donald Trump a few years ago to potentially invest in Pono, went so far as to remove his music from streaming sites a few years ago due to what he considered their poor sound quality. His music has since returned to Spotify, Apple Music and others.)

“I’ve made records for a really long time and what I hear is what I want people to hear,” Young says of the song. “That’s why I make records. So I fear for the way people are going to hear what it is I create because I know how much that end of it has gone down—I think about that. So when I say, ‘I hear Jimi Hendrix’ that means I’m hearing something coming o˜ of a MP3 player through some speakers and it sounds like it’s [coming from] a bad TV or something. It’s very literal. It’s a word-for-word description.” Most of the songs on Peace Trail came to him after his tour with the Nelsons, yet Young is careful to note that they are still elastic enough to live outside any one project. “Each song comes in the room, looks around,” he says. “It either comes or goes— sits down or stands—but it’s by itself. They’re not constructed for anyone else except for themselves. They’re not built so they’ll fi t into what a certain band can play or a certain sound.”

In October, Young was one of six marquee acts handpicked by Coachella tastemakers Goldenvoice to play the classic-rock summit Desert Trip. Unlike most of his peers—who relied on radio-anthems and a catalog of older material to connect with their festival-size audience—Young rolled in with a new band, Promise of the Real, and explored both his cornerstone works and selections from the then-unreleased Peace Trail. He appeared before Paul McCartney both weekends and, since Promise of the Real is comprised of musicians less than half his age, helped bring the event’s average performer age down by a few decades.

“It was wonderful playing there,” Young says. “We booked a whole bunch of other shows in front of it so, by the time we got to it, we’d just be toasty enough so that it wouldn’t matter. We just wanted to be out of it by the time we got out there. We rented this beautiful local place that had a bunch of hot springs and a pool. We had the whole place to ourselves and were together as a band and had a great time. We got through it without it being anything big or different than anything else—but it was still big and different because we were with all these huge bands.”

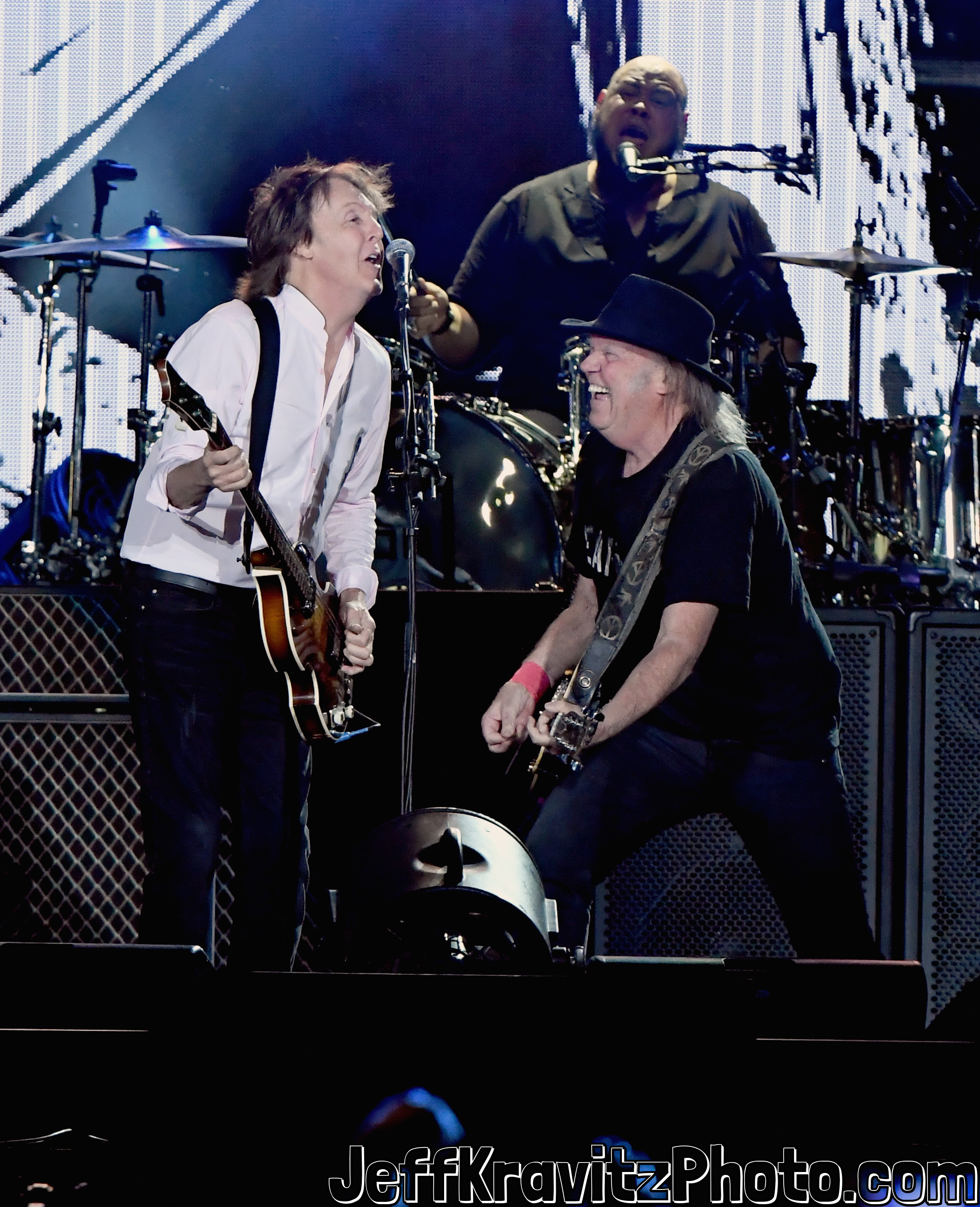

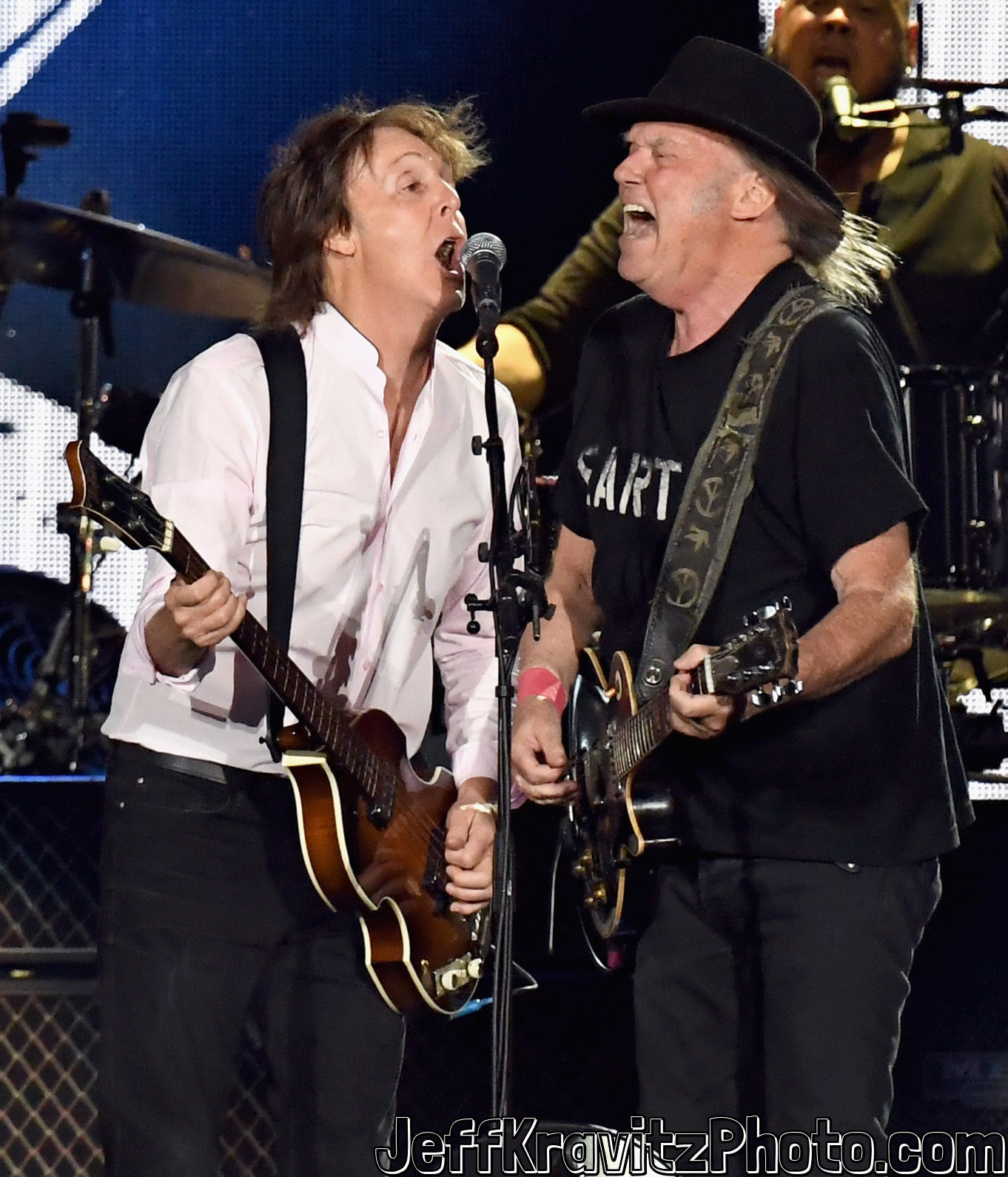

He also offered the dream lineup’s only headliner cross-pollination, joining McCartney for “A Day in the Life,” “Give Peace a Chance” and “Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?” both weekends. (“A Day in the Life” has actually been in Young’s repertoire for years, and he shared a memorable version onstage with McCartney at London’s historic Hyde Park in 2009.)

He also offered the dream lineup’s only headliner cross-pollination, joining McCartney for “A Day in the Life,” “Give Peace a Chance” and “Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?” both weekends. (“A Day in the Life” has actually been in Young’s repertoire for years, and he shared a memorable version onstage with McCartney at London’s historic Hyde Park in 2009.)

Young isn’t sure who made the initial call about reprising the sit-in at Desert Trip but says they rehearsed the song punk-rock style in his trailer backstage. “We were in there just singing, working out some changes and things,” he says. “It’s great to play with Paul—I’ve always loved Paul. We’ve been good friends for a long time and it just grew out of a natural lifetime of things that have happened to both of us, and people that we’ve known in common. He’s such a great musician, and I enjoyed being able to get up there with him and give him something to bounce off of—give him a little bit of something else.”

Though his setlists have rarely been static in a traditional arena-rock way, since joining forces with Promise of the Real, Young has dug deeper into his own songbook than he has in years. His recent string of bustouts have included his first performance of “Piece of Crap” since 2001, the return of “Cripple Creek Ferry” after keeping the song on ice since 1997, the unveiling of “Like an Inca” after a 30-plus year break and even the live debut of the tender 1970 After the Gold Rush favorite “‘Till the Morning Comes,” among other rarities.

He credits Promise of the Real with unearthing some of this material, admitting that he has “a lot of songs I can play at the drop of a hat” with their insistence. “We sat and learned 80 or 90 songs in the span of five days before we even got to rehearsals with Neil,” Lukas says. “Neil was really stoked with the vibe, so we kept going.”

Given that Young has taken on several presidents, wars and countless cultural concerns in his music, it would come as no surprise if he revived any of his older tunes in response to the day’s current political climate. Young brushes off that question, saying, “Well, none in particular. They’re all just individual songs—I don’t look at them that way. I look at them as individual moments. Some of them stand up and ring true at different times as the years go by, and that’s just the nature of it. ‘After the Gold Rush’ is a song that seems to be having another moment, where there’s something about it—I noticed people were relating to it strongly during my last group of shows. It’s funny the way it just comes and goes, but I’m just doing what I’m doing— writing songs as I feel like writing them and then playing them.”

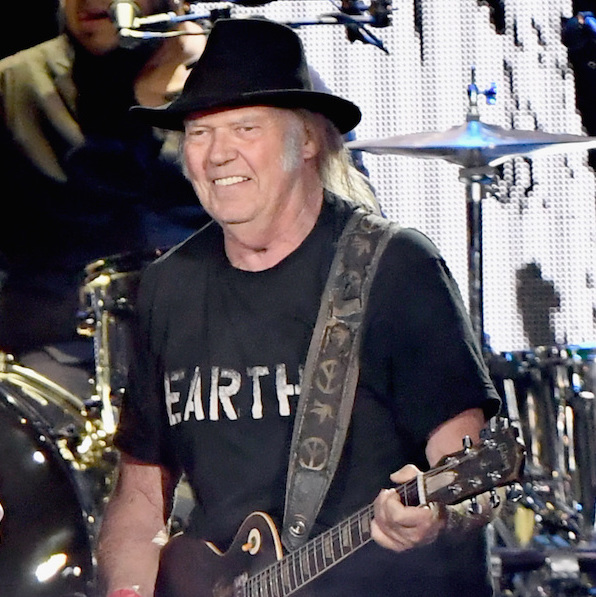

He did, however, decide to capture his instant connection with Promise of the Real on the double-disc, triple-LP live set Earth. Far from a traditional concert souvenir, Earth is a carefully curated survey of Young’s stories concerning the land and living together in this world. It’s also something of a studio-show hybrid, buffing up Young and Promise of the Real’s raw stage performances with animal sounds and effect . He already considers it among his favorite records.  “I put so much love into it and so much care into making it,” he says humbly. “We broke the rules of making a live record; we weren’t trying to make it sound live. I think our post-production on Earth was about four months—there’s a lot of layers to what we did to those live performances, while still maintaining the live mix that came out of the PA. We didn’t remix them, but we did add obvious overdubs and used them in ways that were more like a novel than a record. There were all these other ideas happening, like it was part of something—a bigger picture where, if you zoomed in on it, it was live. But if you pulled back, there were a lot of things going on. It’s an Earth story.”

“I put so much love into it and so much care into making it,” he says humbly. “We broke the rules of making a live record; we weren’t trying to make it sound live. I think our post-production on Earth was about four months—there’s a lot of layers to what we did to those live performances, while still maintaining the live mix that came out of the PA. We didn’t remix them, but we did add obvious overdubs and used them in ways that were more like a novel than a record. There were all these other ideas happening, like it was part of something—a bigger picture where, if you zoomed in on it, it was live. But if you pulled back, there were a lot of things going on. It’s an Earth story.”

The album is also a choice document of one of Young’s most exploratory projects yet. Lukas, in particular, has deep ties to the modern jamband scene and has fostered a close relationship with Bob Weir. More than any of Young’s bands since Crazy Horse, Promise of the Real have proven to be his ideal improvisational sparring partners. “Neil is one of the ultimate jammers—not many people go as hard as he does, in terms of full-on open jamming and he’s never slowed down,” Lukas says. “He was a huge part of my roots along with the Grateful Dead, Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan. That, along with the great old country music I listened to through Dad, really makes up who I am.”

“It’s very healthy; you gotta trust yourself,” Young adds. “It feels excellent, and there’s nothing about it that’s not free. It’s full of whatever is happening. So there’s no way you could compare that to anything. It’s not better or worse. It is what it is.”