Will the Real Citizen Cope Please Stand Up?

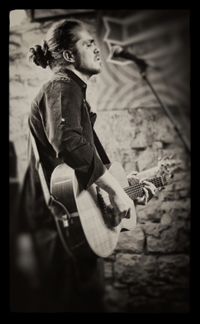

Photo by Alex Elena

A stack of old concert posters is piled on the kitchen table and Clarence Greenwood is bent over them, pen in hand, scribbling his autograph – or rather, he’s signing his stage name, Citizen Cope. He stops and looks at his merch man Keir with concern. “I just signed 2012 on a 2011.” He thinks for a moment, and then shrugs it off.

Six days after a four-week tour, Cope is still winding down. His gear is still in his car, his suitcase still sits unpacked on the TV-room floor and he moves like molasses, as if he could easily sleep for 24 hours straight if given the chance.

Then again, maybe that’s the natural gait of this laid-back singer/songwriter. It seems to match the slow, semi-Southern drawl and quiet, slightly slurred quality of his speaking and singing voice.

Keir grabs the newly signed posters and takes off. Cope finds a large white container in the fridge, scoops an unnaturally green powder into a glass and mixes a power drink. The spoon quickly and loudly clinking, he says with a coy half smile, “My fish food.” His blue eyes twinkle. When he’s done stirring, he hunkers down for a chat.

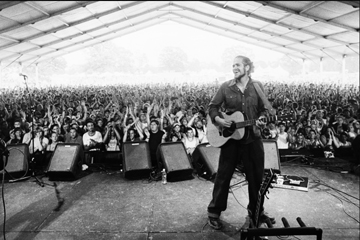

“I’m at a real transformation point right now. The intensity of the way the music has touched people is pretty profound,” he says. “Doing shows, you try to do it like it’s the last time you’ll do it. These people love you. They spent all this time to go there. And I love them; I don’t want to let them down,” he says genuinely. Then he adds, compelled to explain why the pressure is worth the effort, “When you carry that kind of intensity, you’re bound to get something back from it.”

This month on the road comes on the heels of releasing his fifth album, One Lovely Day. It’s been ten years since his eponymous debut album and the contrasts between these two efforts are as subtle and stark as their similarities.

Stylistically, they share the same breezy, calm tone – soulful, rhythmic, pop-like. His latest, though, feels more cohesive – even to him. His consistent mellow singing drawl now has a crisper delivery. The lyrics remain personal, but the stories aren’t told through characters anymore. Instead, Cope puts himself entirely in the first-person spotlight. One cut on the new album, “A Wonder,” directly (and, by his own admission, subconsciously) references “Contact,” a song from Citizen Cope that he rarely even plays live anymore. But the biggest difference between these records is that Cope’s in total control – writing, producing and now releasing his albums on his own label.

“I remember, early on, saying a prayer that I could just do something authentic and not necessarily be about personal achievement,” he recalls. “If it could be authentic, then I felt like it would reach people. That’s the best thing that you can have.”

Staying true to himself while finding opportunities to attract and connect with fans has been an epic challenge. His journey has been frustratingly complex, but it started simply.

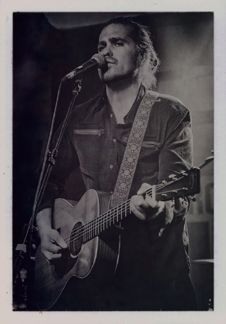

Photo by Alex Elena

He was 18 years old, a recent graduate of the Washington, D.C. public school system. Following high school, he moved to Texas to be with family after the uncle with whom he shared a name passed away. The impact of that loss manifested itself in a writing binge.

“He was a very dominant figure in my life,” Cope explains. “I was looking for some answers, not only about that, but outside of that as well.” He started writing poetry and quickly found it coming out in torrents. “Shit was just comin’ off the pen.”

He got a drum machine and started organizing his writing into spoken word, which, in turn, led him to start writing songs. “I liked a lot of the hip-hop stuff going on, so I started learning how to sample, trying to understand how to put a song together.”

Taking advantage of open enrollment at Texas Tech in Lubbock, a few hours from the small town that he lived in, he found that a few teachers inspired him. “I guess when people give you positive reinforcement, you can get somewhere you didn’t expect,” he says.

But his college career would be short-lived. He dropped out after a year. “I knew there was something for me; I just knew it wasn’t where I was at,” he says. “Where I landed wasn’t where I was supposed to be.”

He spent a couple of years in Austin, working on music, buying and selling concert and sporting event tickets to make ends meet – a talent that he’d picked up as a kid. Eventually, he headed back to D.C., still scalping tickets as he put together a demo.

Michael Ivey, frontman of the D.C.-based alternative hip-hop outfit Basehead, was among those who heard it. With an album done, Ivey asked Cope to join him on the road to work the sampler and to DJ.

“I was like. ‘I don’t do that. You should find someone who does.’ And he was like, ‘No, I like you a lot. Your music’s gonna be good, so you need to learn this shit,’” Cope says. The tour took them to Europe for a couple of months. And they spent a couple more in the U.S. “I was just learning at his expense,” Cope remembers, “which was great.”

When Ivey stopped touring, everyone resumed what they were doing before. For Cope, that meant selling tickets and writing music. Using the money that he’d made scalping tickets at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, he financed time in a studio outside of D.C. He recorded five tracks, among them a song about one of his scalping “colleagues,” an older man called George.

“That wasn’t his real name,” Cope clarifies. “He’d say he was from Greece; then, he’d say he was Italian. He had a New York accent, but he lived in Baltimore. He’d been around.”

Fans should recognize him as the subject of one of Cope’s most popular songs. “He was like a more worn Harry Dean Stanton, but real frail and short. He was a real weasel-ly character,” he remembers with a sort of bittersweet nostalgia. One day, after George had a big night, he showed up asking for money to start his workday. Cope outright asked him “George, what’s the most money you’ve ever had?” The answer, only slightly modified, became the song title, “200,000 (in Counterfeit 50 Dollar Bills).”

Cope made calls, sent his music out and played open mics around D.C. He was gaining a small following as interest began building. A well-timed, positive article in the Washington Post and a discovery of his demo in the unsolicited pile at a major label sent him into the whirlwind that would be his adventures with recording contracts. It began with a demo deal from Capitol Records that turned into a full contract.

Photo by Alex Elena

“There was a great excitement when I got my first deal at Capitol – like my life had changed,” Cope says of the 1997 signing. “I had been struggling – trying to become a songwriter – selling tickets and now, I could go make a record, get a big advance, walk into a bank with 75Gs and say, ‘Open an account.’ That shit was big. Then, later that year when the IRS took half of it, I was like, ‘Oh shit! Now, I’m broke again.’” He chuckles good-naturedly. Soon he discovered that there wouldn’t be any more money coming from the record, either.

He found himself in a tug-of-war with “this record company figure that was supposed to be like some Don Corleone guy.” He was asked to rerecord the same songs multiple times while the label looked for radio- and TV-friendly singles on an album that Cope intended to be “about underground themes.” Eventually, the project was shelved.

“I couldn’t believe they would spend that much money on a record and then, not put it out,” he says, matter-of-factly with just a hint of frustration. “There were some mistakes I made on that record. I think my original demos were the most powerful. I probably should have stuck with those instead of rerecording them,” he admits. “I think I was just chasing after those songs.”

Without an album and bound by a rerecording restriction, Cope was back at square one. He started rehearsing in a friend’s studio, concentrating on vocalizing – pushing his voice.

He penned “If There’s Love” and flew to Atlanta to record it. And he convinced DreamWorks to finance recording his demo, only to have them pass on it afterward. This time, Cope kept the rights and took it to New York to try his luck. When a line of labels formed ready to sign him, DreamWorks came back and offered a contract. Grudge-free, Cope signed and his eponymous debut came out in 2002.

Now living in the Ft. Greene section of Brooklyn, N.Y., Cope was already back to writing new material, including “Sideways” – a tune that, contrary to its name, only would take him upward.

“I’d been writing it and had it in a high form of incubation and then, it just,” he pauses, “came. I remember writing the song and then getting inspired seeing some beautiful woman. It wasn’t about her, but it took it over the top. I went back and finished it, and it became really powerful.”

He went into an New York studio to record, nailing it in two takes. “I recorded it live with the drummer in the same room and Meshell [Ndegeocello] was in the control room playing the bass,” he says. “There was just something about it when the recorded version came out – people liked it.”

But the reaction from the folks at DreamWorks wasn’t what Cope had hoped for. “They were kinda lukewarm on it,” he says.

Meanwhile, Arista heard “Sideways” and passed it along to Carlos Santana’s manager. “The manager liked it, Carlos liked it, Carlos’ family really liked it,” Cope says. “It was done. I had recorded it. I talked to him and he didn’t want to change it. He didn’t want to rerecord it. He just wanted to play guitar on it.”

Fresh off of a full-day video shoot for “If There’s Love,” Cope flew out to San Francisco. He was crammed into an economy seat with a stop in Chicago. No sleep. Once he landed, he didn’t even bother going to the hotel. He headed straight to the studio for a noon session and got to work. Topping it off with some percussion, guitar and organ, plus a few engineering tweaks, the track was done; but it wasn’t until the day before Santana’s Shaman was released in 2002 that Cope knew “Sideways” had made the cut. (He would later go on to perform “Sideways” with Sheryl Crow in front of tens of thousands of music fans at Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festival in 2010. Clapton would invite him to play “Hands of the Saints” with him, too.)

His path was clear. Cope bought out his contract with DreamWorks, signed with Arista and started work on a new album, The Clarence Greenwood Recordings_.

_Photo by Danny Clinch

With the A&R team at Arista including LA Reid, Pharrell Williams and Jermaine Dupri, among others, heavy-hitting producers were available and interested. “But we knew that one of those songs with one of those producers would eat up the budget and change the sound,” he says. Besides, what Cope was putting together on his own was working.

“This guy from Arista came in and … it was such a breath of fresh air to have him react with such positivity,” Cope recalls. “He said, ‘Hey, man, just keep doing what you’re doing.’ It was a great vote of confidence.”

Things were looking good. “LA Reid really loved the record and [told] the staff to make me a priority,” Cope says. “I didn’t have management at the time, so they pretty much did everything for me. It was a really positive, good vibe from the people who loved you there and understood you…. It felt like an inclusiveness that I’d never felt.”

By the time that Cope returned from playing some European dates with Santana, Reid had been fired. Arista was absorbed into the RCA Music Group, and so was Cope’s contract. The album came out in 2004 on RCA but saw poor sales. Cope went back into the studio and came out with Every Waking Moment in 2006. RCA wasn’t in love with the album. Cope wasn’t in love with his experience at RCA. When the label asked him to pick up another option, he declined.

As ready as he’d ever be, he struck out on his own, preparing to do things his own way. Without a label advance, he toured to make the money that it would take to make a record, adding acoustic shows to minimize what he was paying out of pocket.

“It took me a while to even get into the black,” he says. He got back to writing as much as he could between touring. Not only did he write, play and produce what became The RainWater LP, but he also manufactured it.

“We were out there putting the packages together. It was like a 20- or 30- step process in this huge, cold, dusty warehouse,” he says. “I spent a fortune on printing. Just ridiculous.”

The album came out on his newly formed label, RainWater – his Uncle Clarence’s last name. One Lovely Day is his second indie release. And though he hints at a potential major label partnership for his next album, he’s intent on keeping control going forward.

Success for Cope now, he says, is “when you feel like you’ve done something and you’re alright with it artistically, and you feel like you can recognize something is good, even if you can’t recognize it as great yet. Deep in your heart, you know that it’s positive, that it works; your vision kinda got there. And that’s how I feel when I finish a record – hopefully. That’s all you can ask for.”

“It’s ten to four,” Cope’s assistant pops in to remind him. He checks his phone to verify, and soon, he’s through the baby-proof gate on the stairs, putting on a thin, fall jacket and walking down his quiet, tree-lined Brooklyn street. It’s a windy Friday in October and the sun has finally peeked through what has been an otherwise cloudy sky.

He’s en route to pick up his 21-month-old daughter from school, and he’s talking about his own childhood. He was born in Memphis, Tenn., and his parents divorced soon after. He moved to Greenville, Miss., with his mom and after she remarried, the family relocated to D.C. – but he spent summers in Texas with his father’s side of the family.

He remembers jamming to The Jackson 5 with his older sister, playing 45s and enjoying music in the car. He recalls listening to Neil Young songs and trying to play them on one string.

But the moment that music had its full impact, he says, was in seventh grade. “This guy played the horn,” he remembers. “They say he was related to Dizzy Gillespie. It was at an assembly and the gospel choir sang this song ‘Thank You, Lord.’ It was something magical. It made me feel so good.”

Two years later, when young Clarence joined the gospel choir himself, he was singing the lead on that same song. It was his first public performance.

“My voice hadn’t changed and the part was really high. I was already getting hella teased about being small and underdeveloped, and my voice was already high. So, I was singing this really high part and thought I was just gonna get hell forever. But I sang it and everyone loved it.”

Still, to this day, he’s pushing past his own doubt, trying to learn and to grow, overcoming whatever surprises life brings. Somehow it all works out for him eventually.

His fanbase continues to grow. He’s been invited to join Clapton again at an upcoming Madison Square Garden show. And despite the past drama of labels looking for TV angles, Cope’s songs have appeared in shows like Scrubs and Entourage, films such as Battleship and The Sentinel, and a commercial for Pontiac. Yet, he denied the license for “Sideways” to one commercial based on the stills. “I was like ‘Man, they’re gonna ruin this song,’” he says. “I don’t have a problem licensing it to a commercial. It’s just…there was something about it. I probably would have been a very wealthy man.”

Cope always goes with his gut. And maybe that’s what resonates, what appeals to his intensely dedicated fans. Here’s a man who, after all this time, puts himself on the line simply because he wants – as he sings in the song – some contact “only because my life depends on it.”

“It’s been a learning process,” he says. “How do you perform? How do you let these people in? I’ll look at somebody and – I know this has been said before – but you kinda see yourself in them. We’re all the same people. We all have our own insecurities and our own struggles and traumas and joys and pains. I think if somebody connected to the record and it helped them, then I think they have a common thread with me somehow.”

He’s arrived at the school and he has his baby girl on his hip. Her golden curls are pulled back like daddy wears his signature dreads. The same sky-blue eyes look into his. He turns to the rest of the class and says, hello. They sit, cross-legged on the daycare floor, looking up at him. A few smile and one waves.

“Did you figure it all out yet?” he asks the class earnestly, waiting for a reply that doesn’t come. “We need you to find the answers for us.”